The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

By

Benjamin Franklin

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Faculty, librarians, and students of the University of Virginia , Ellen French, Andrew Michael, Natalie Thompson, Monica David, Spencer Brown, Lizzie Rusnak

n9999(Draft)Here the page numbers return to 191. As Franklin wrote this over many years most likely this means he lost his place and didn't have the papers with him as he continued the manuscript.Franklin

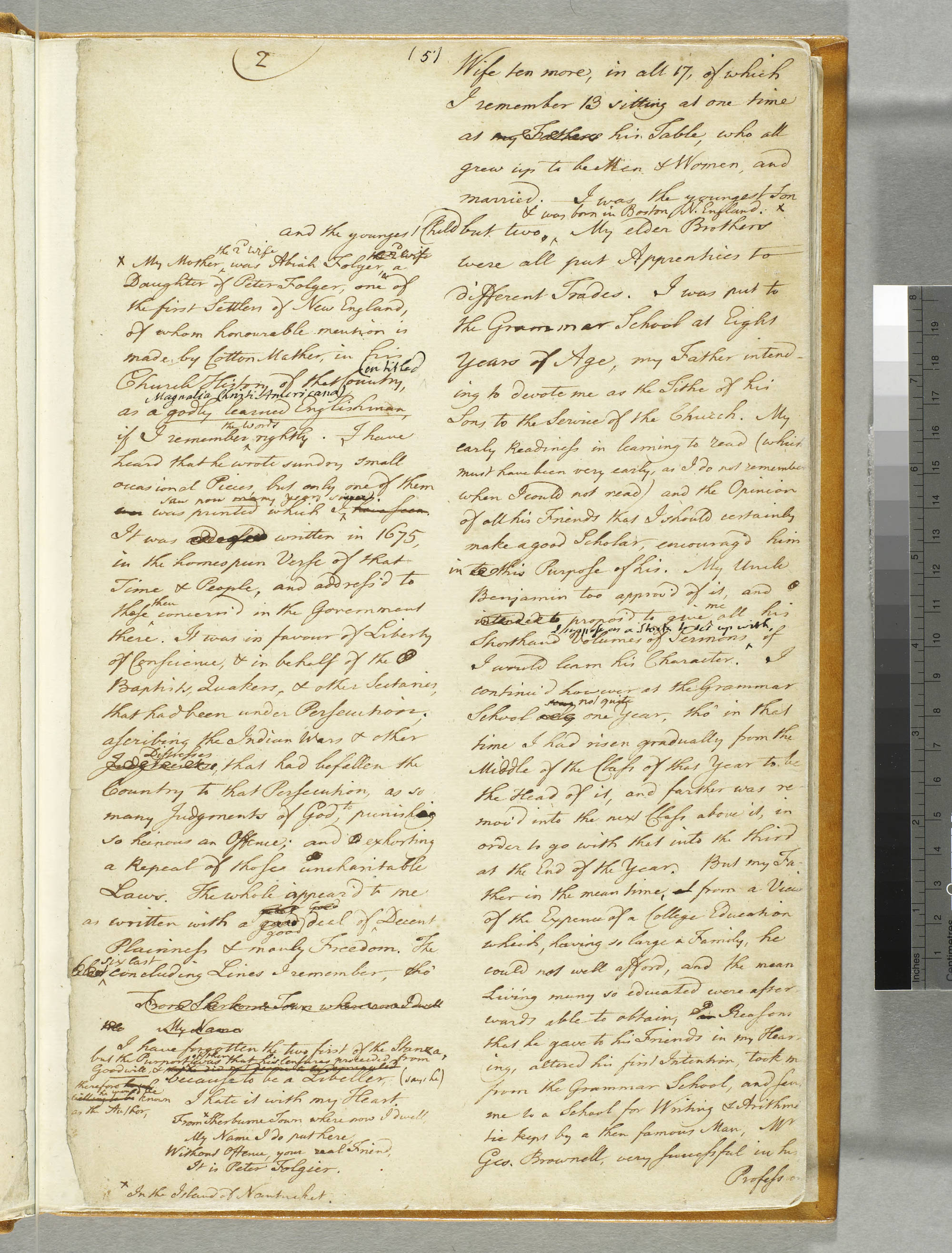

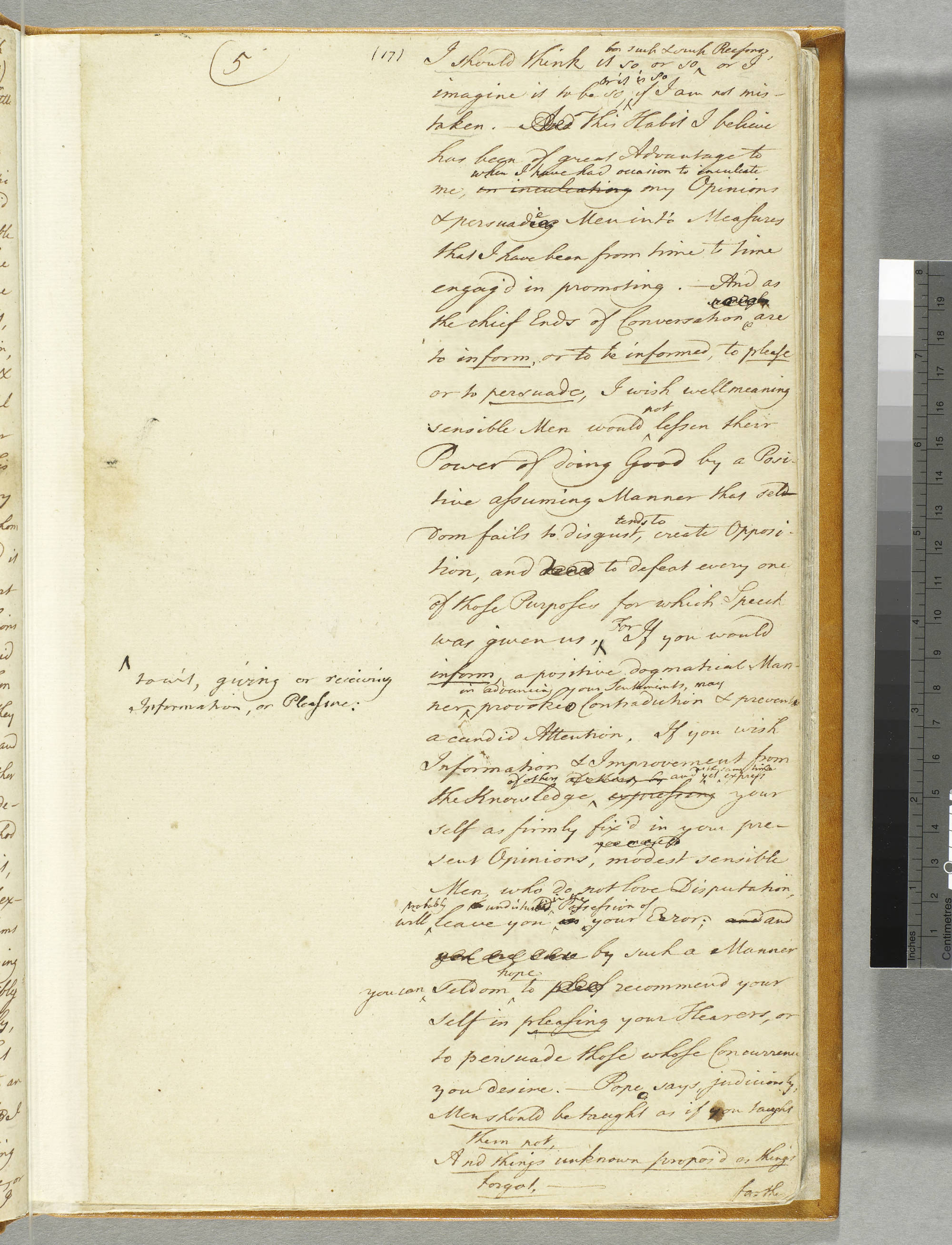

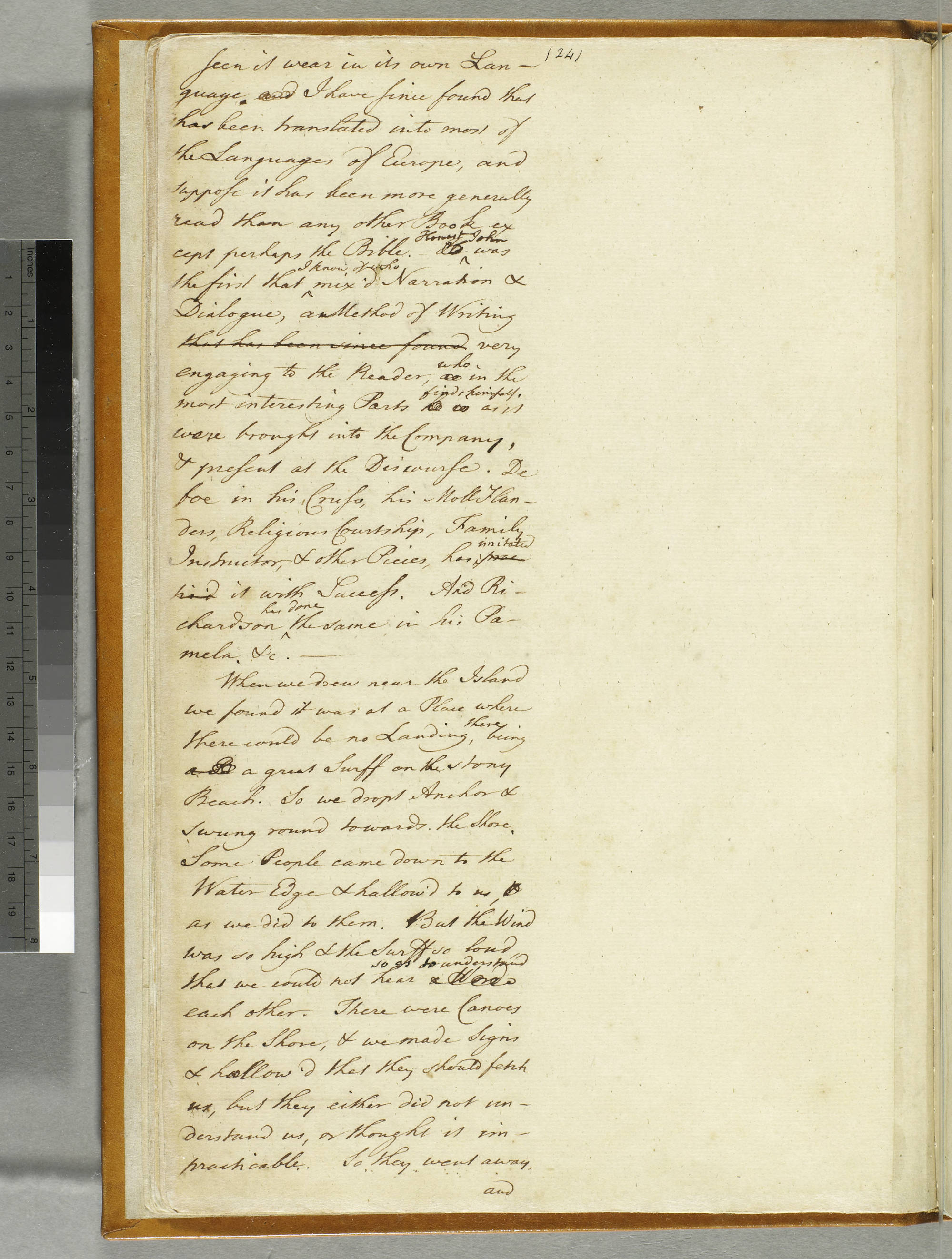

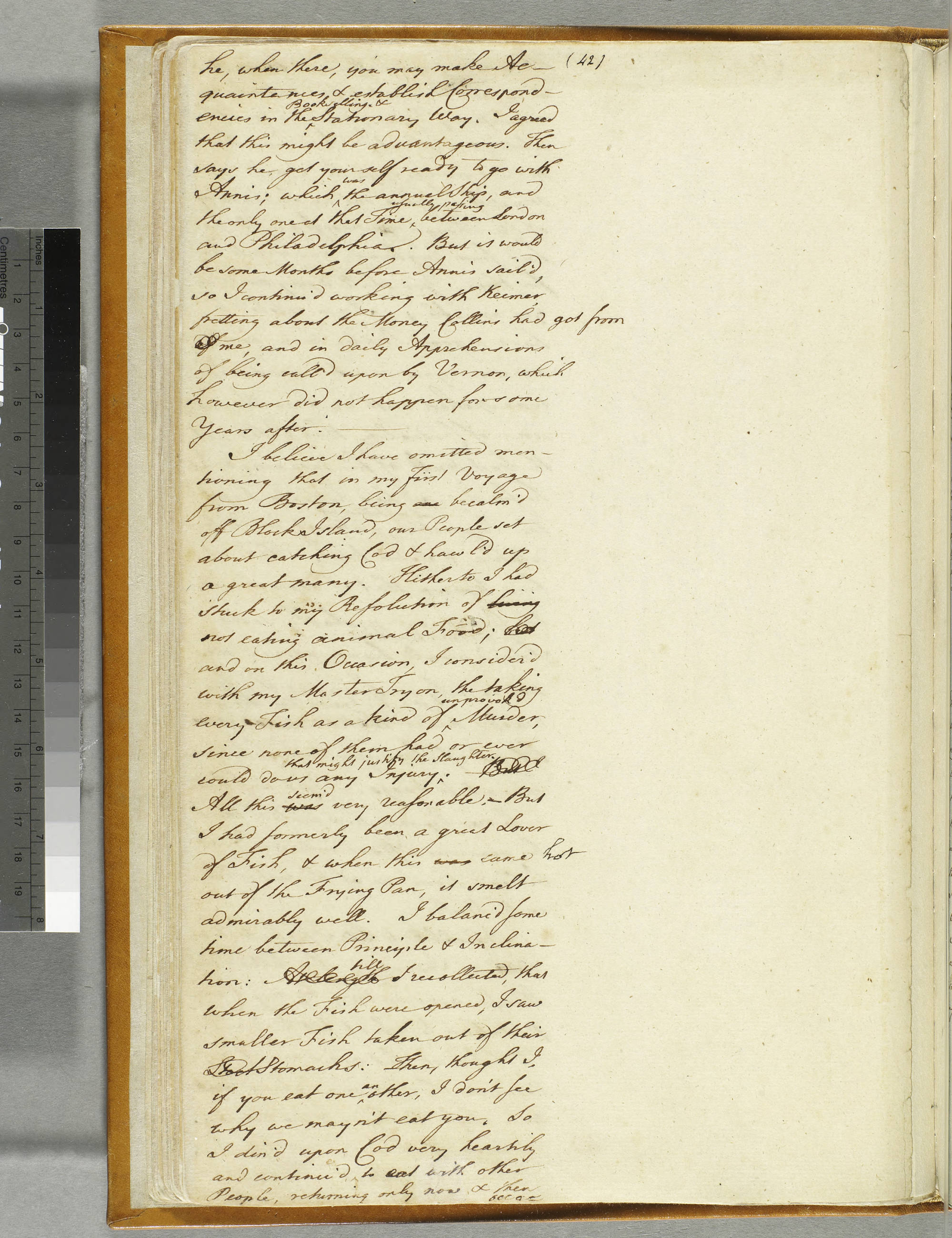

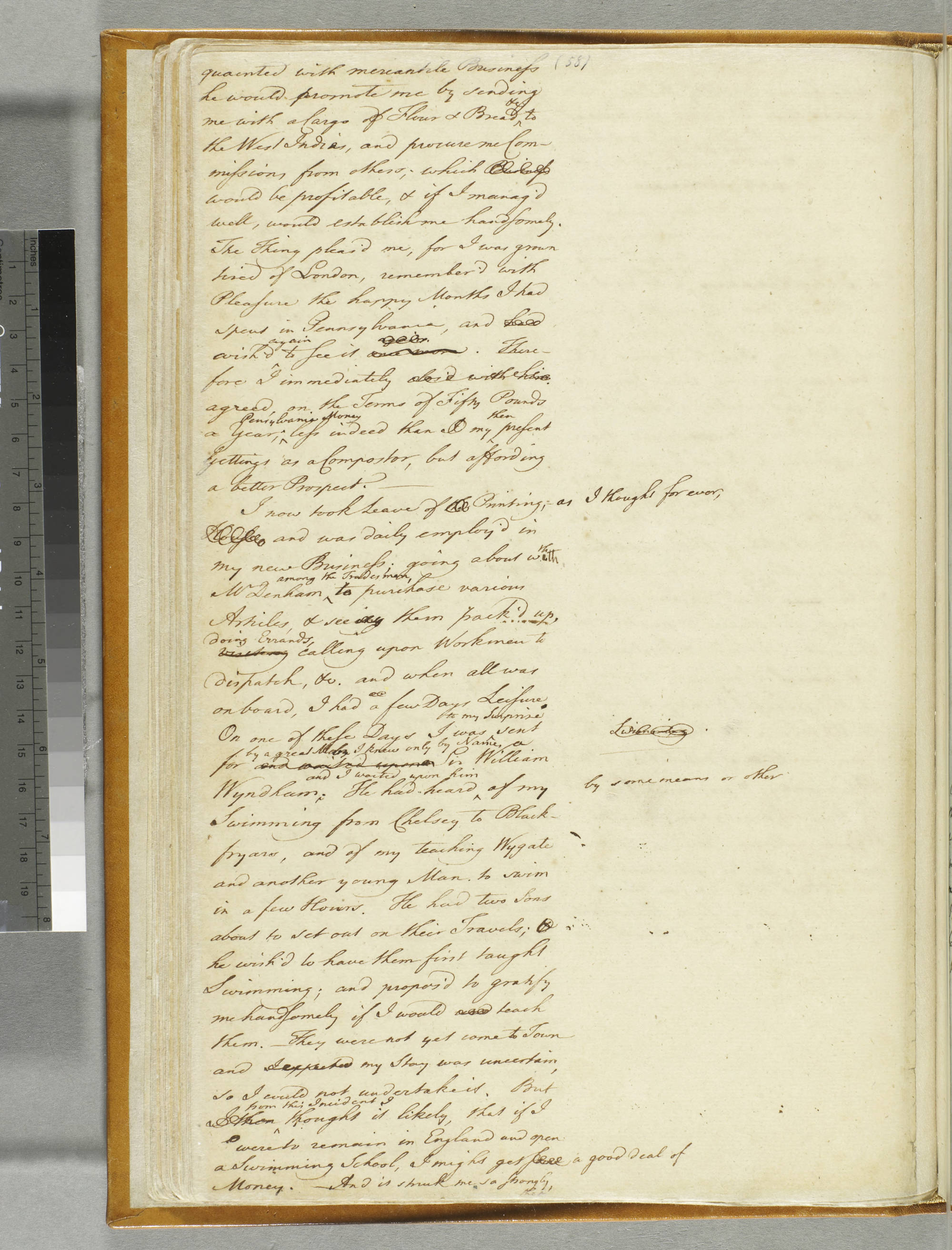

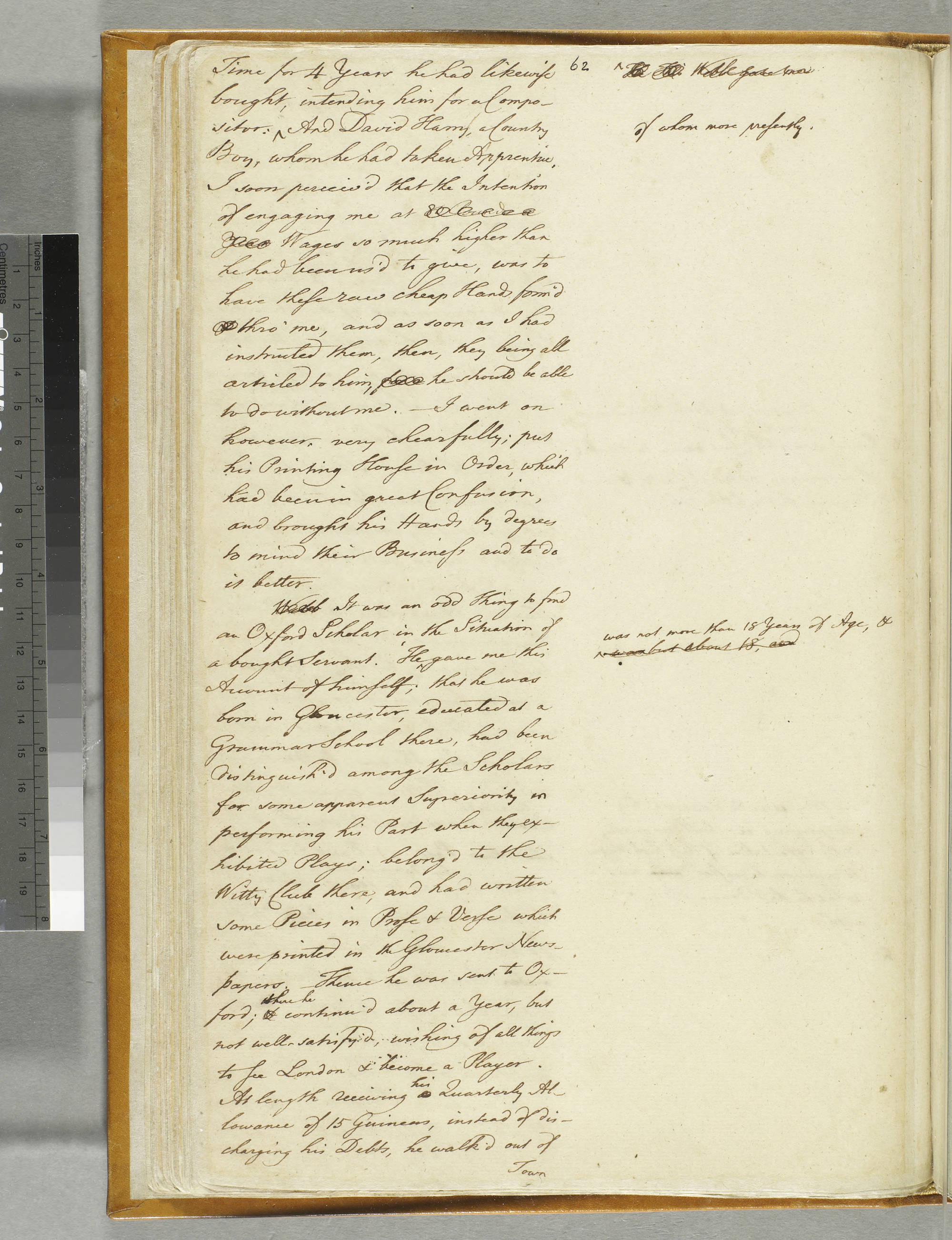

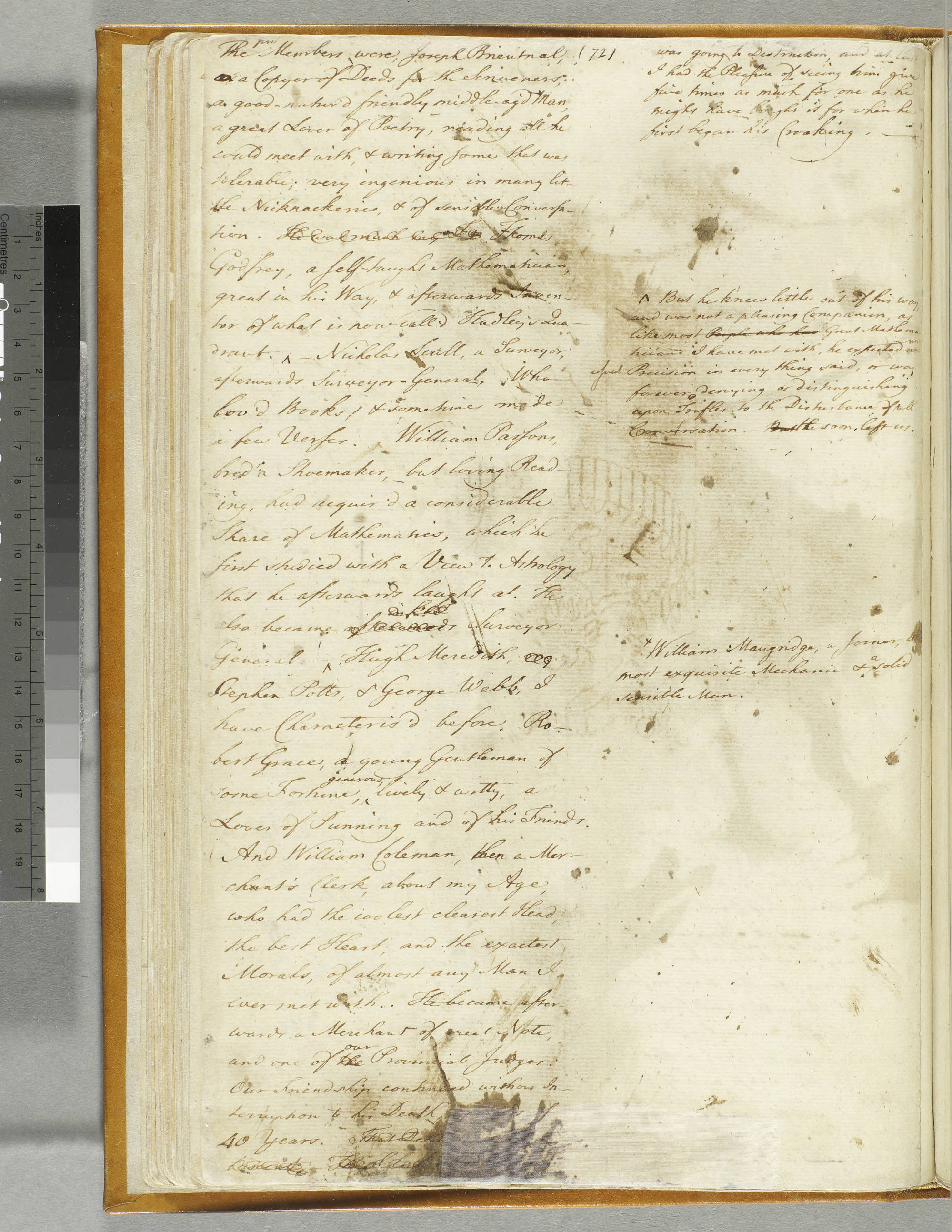

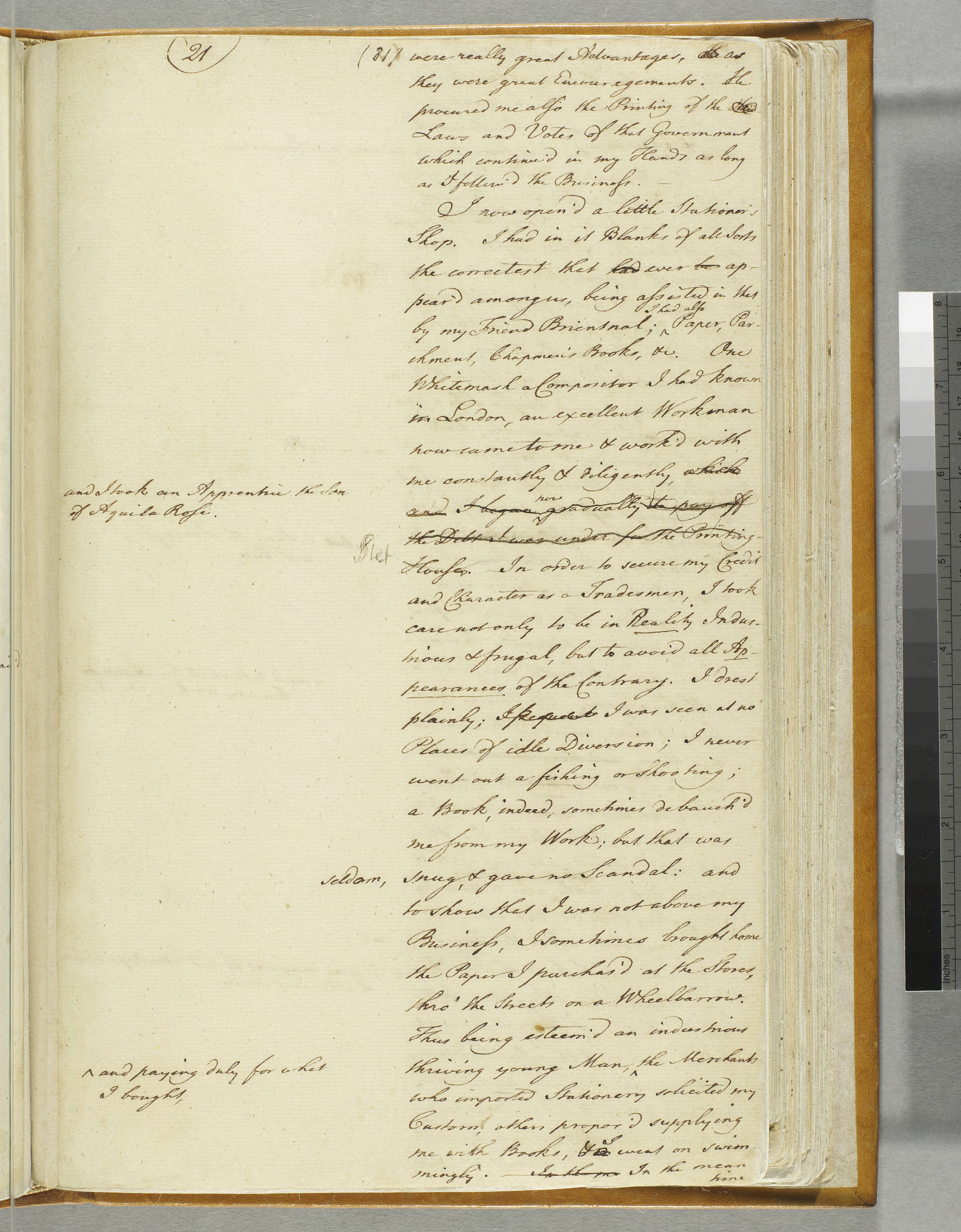

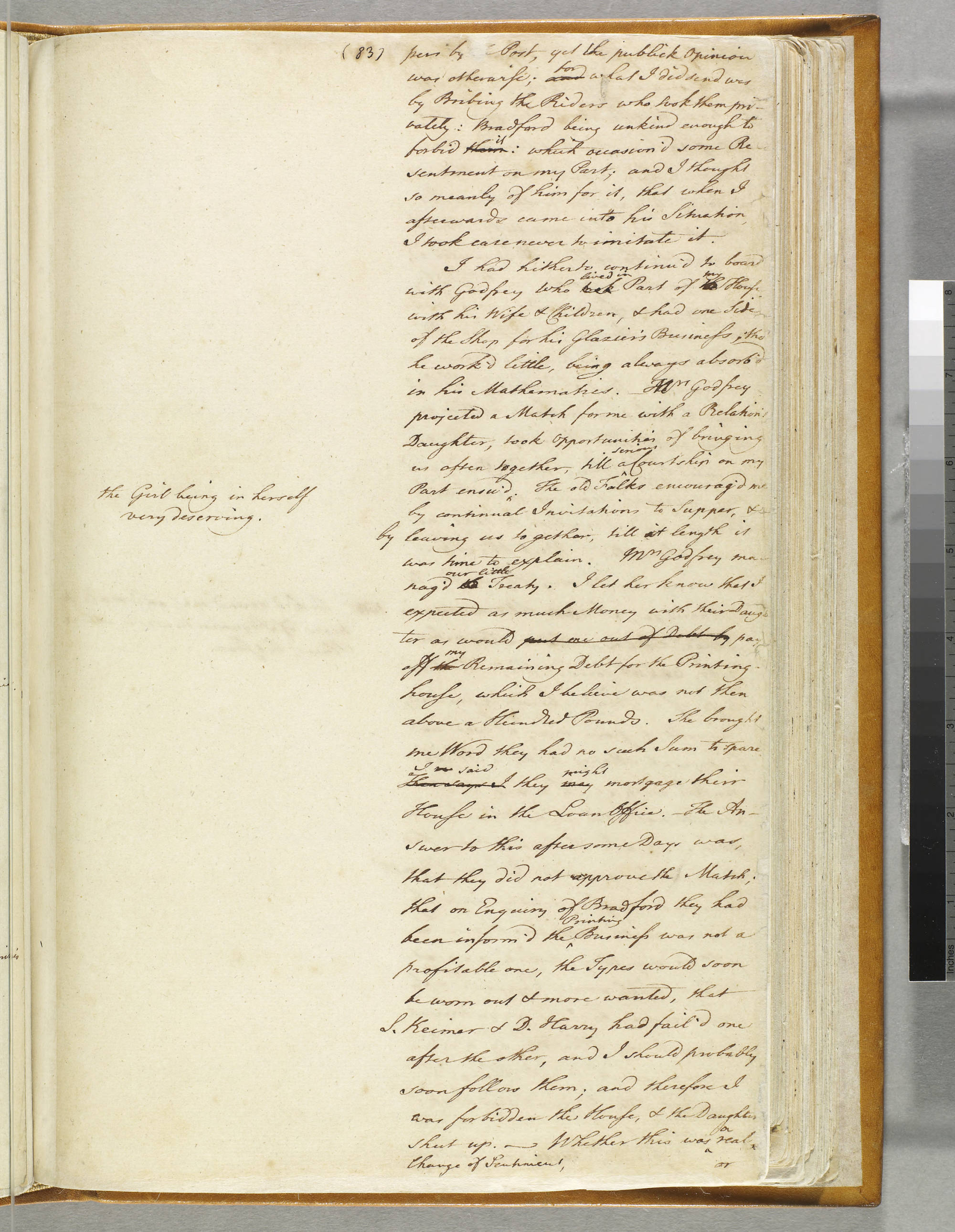

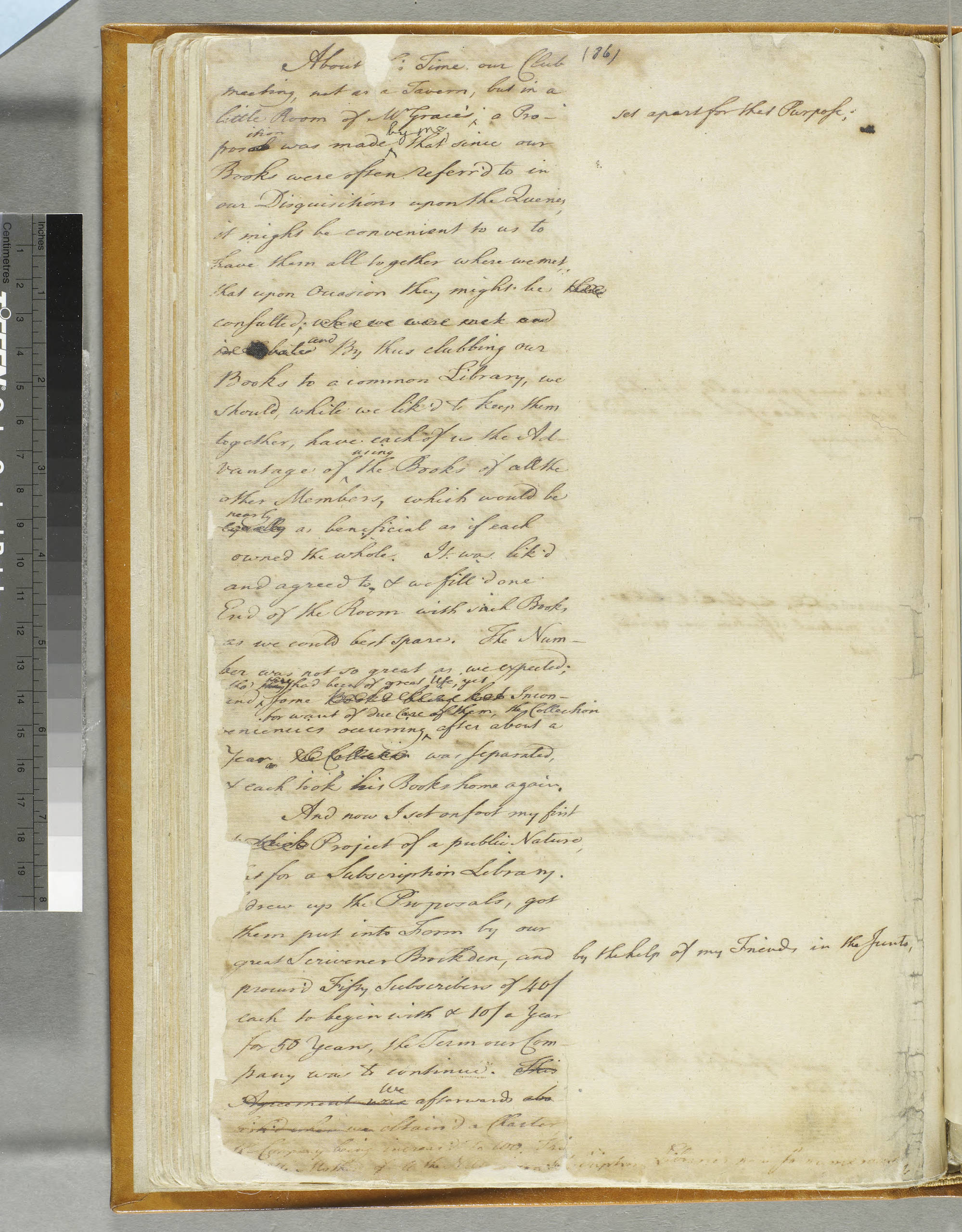

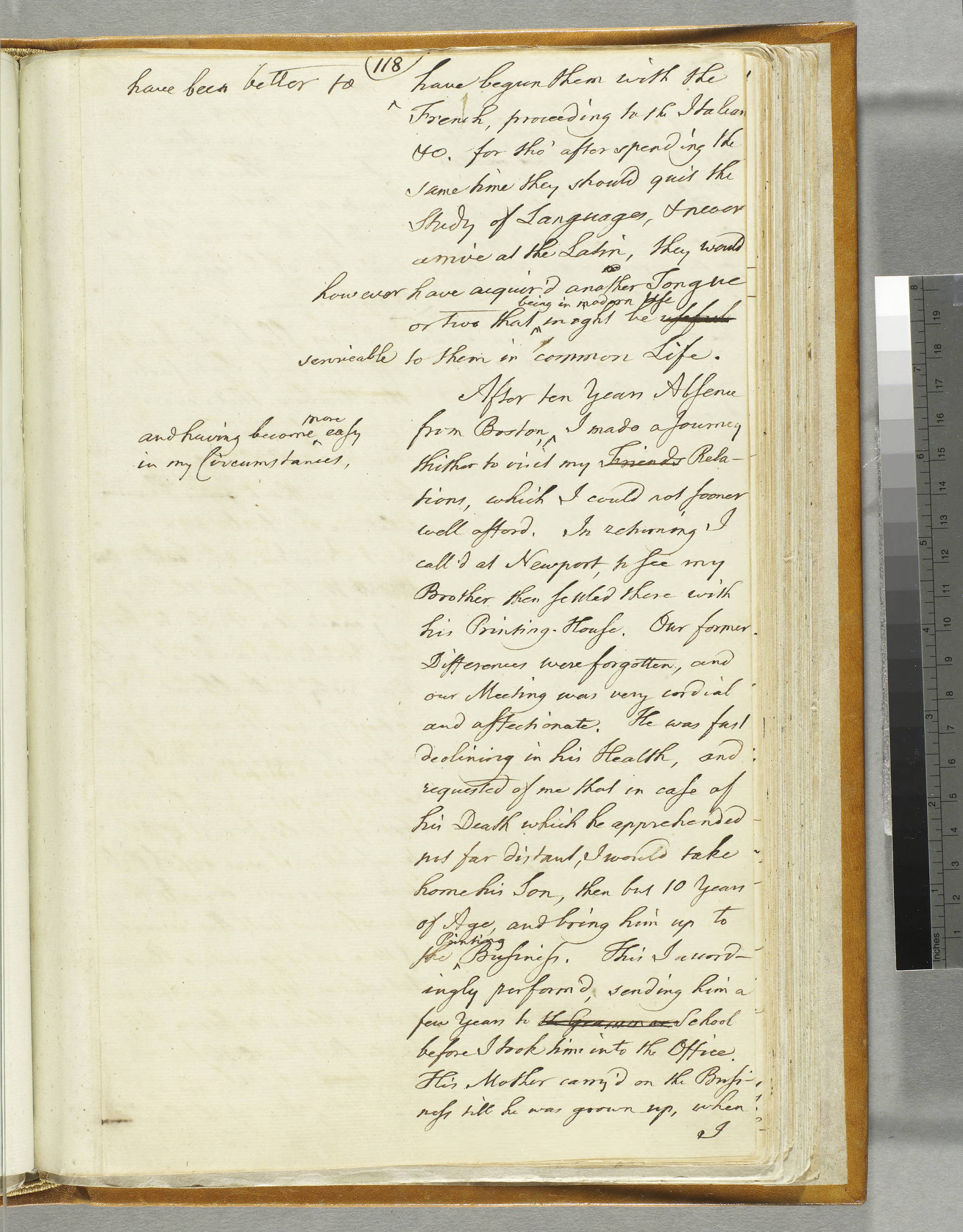

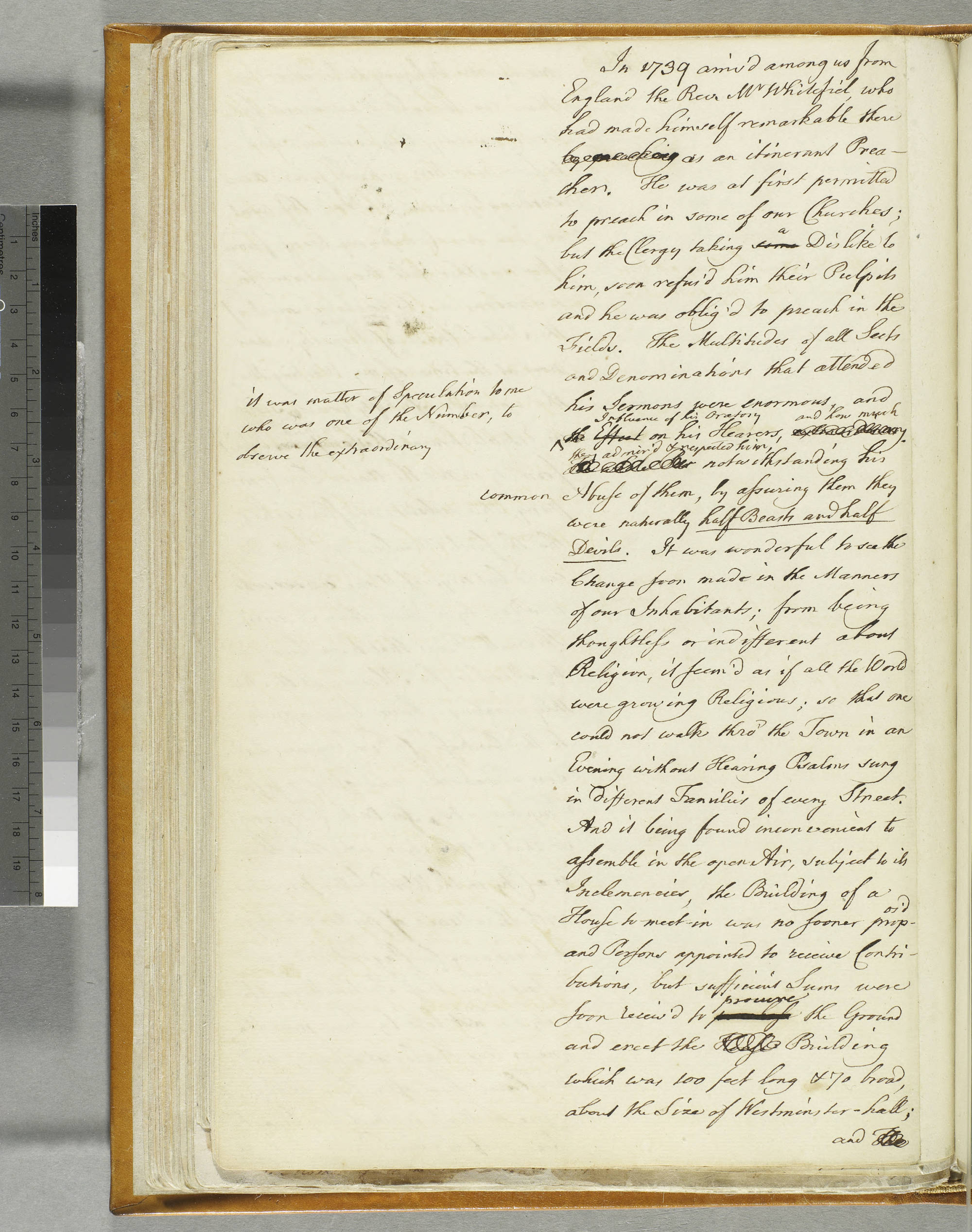

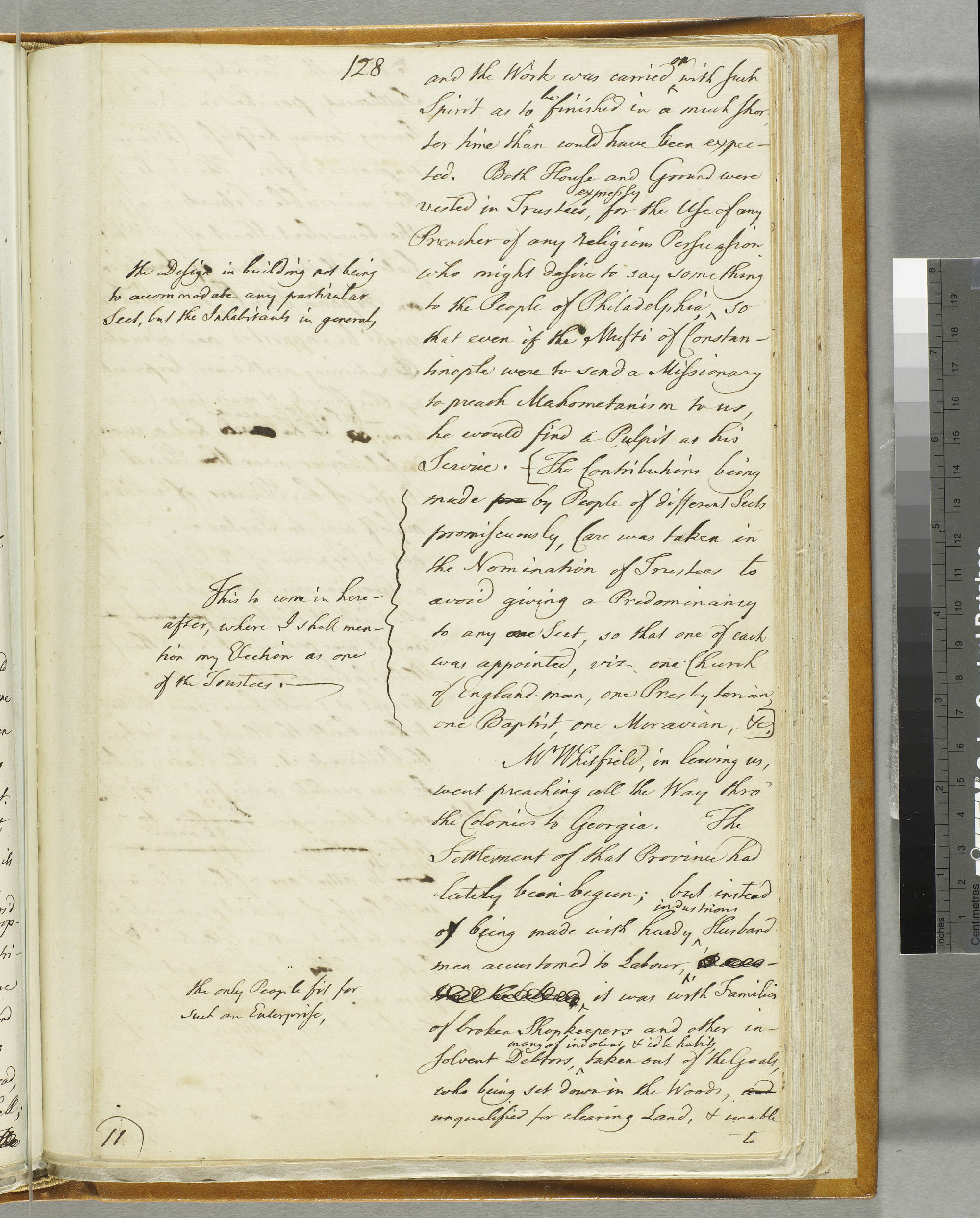

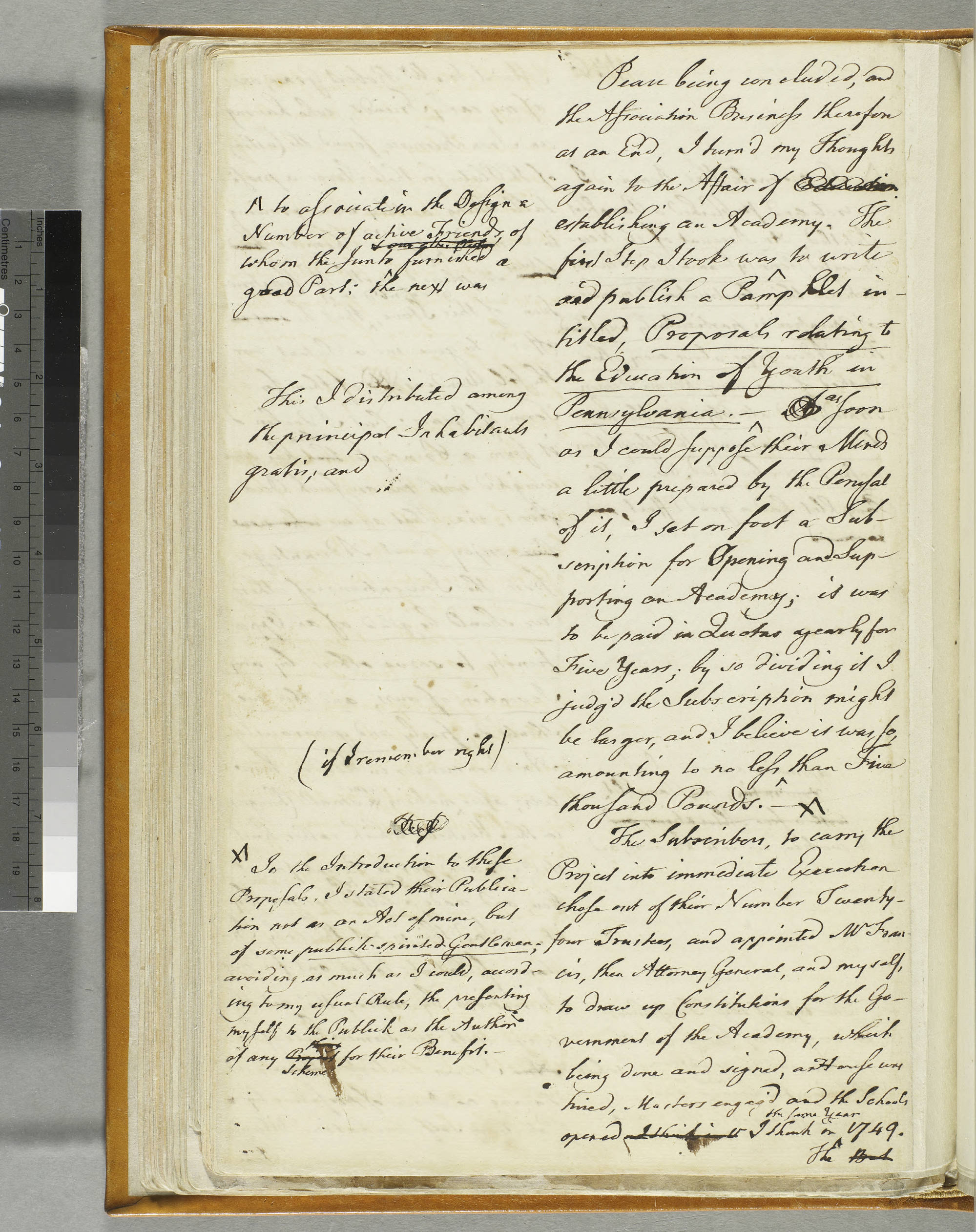

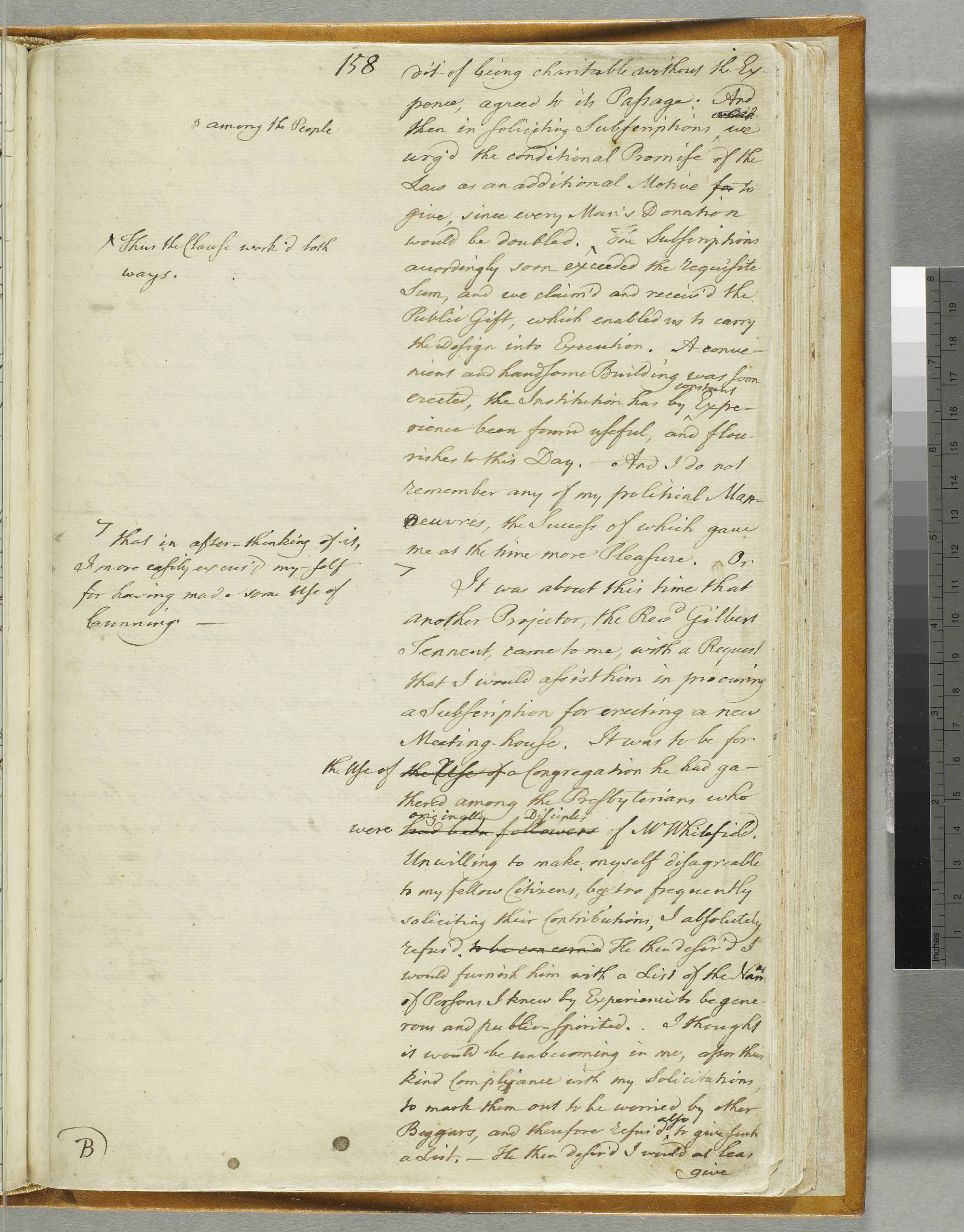

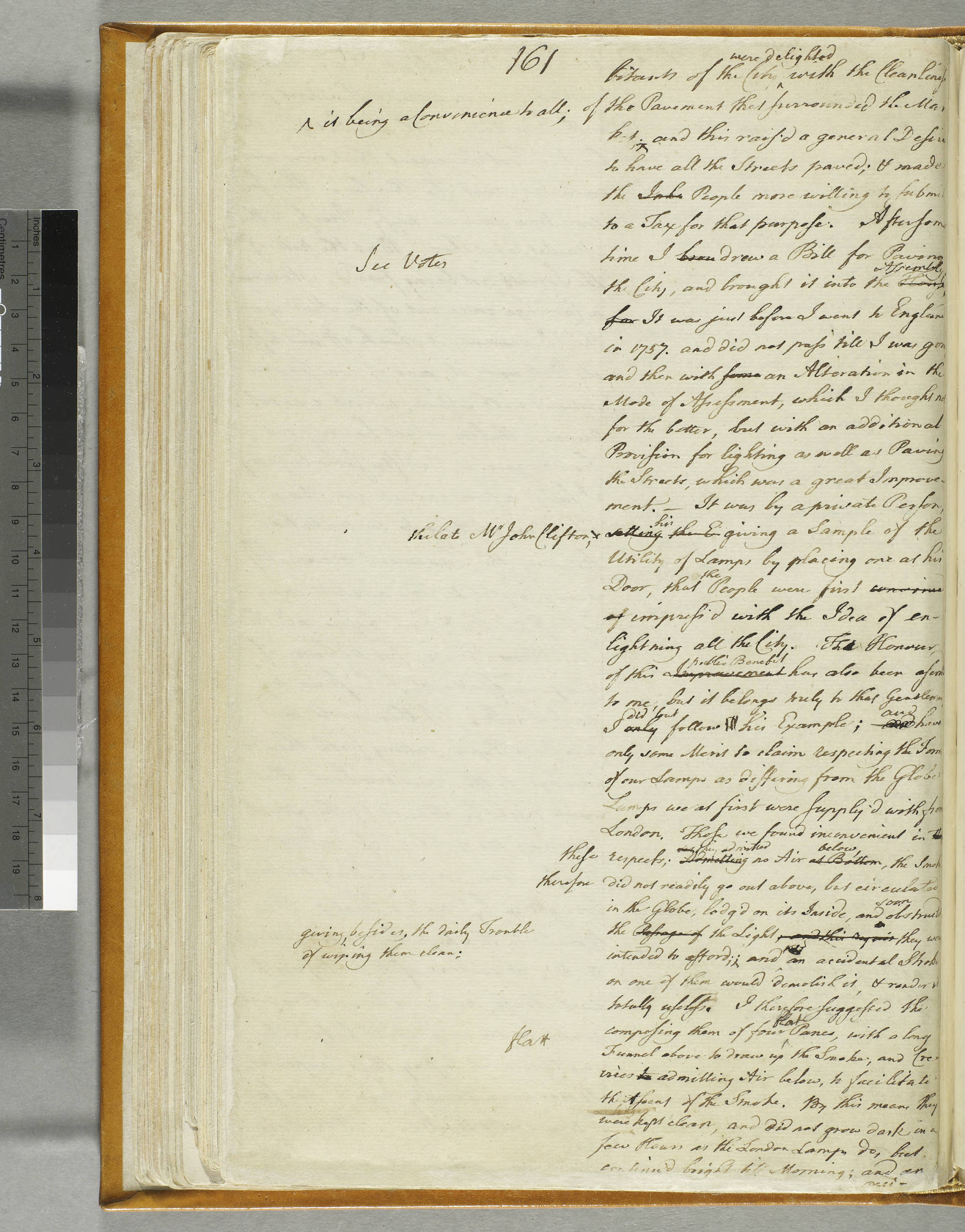

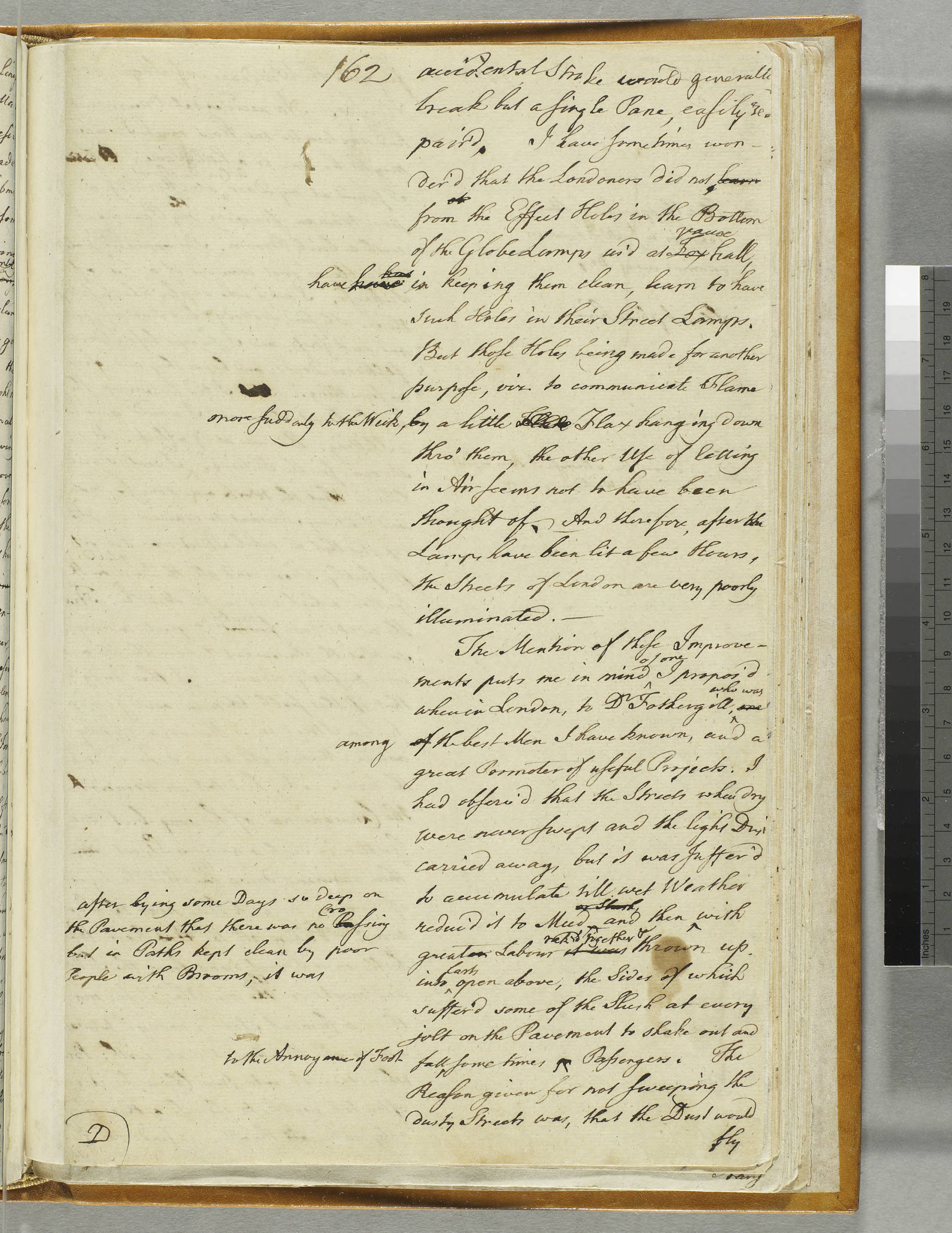

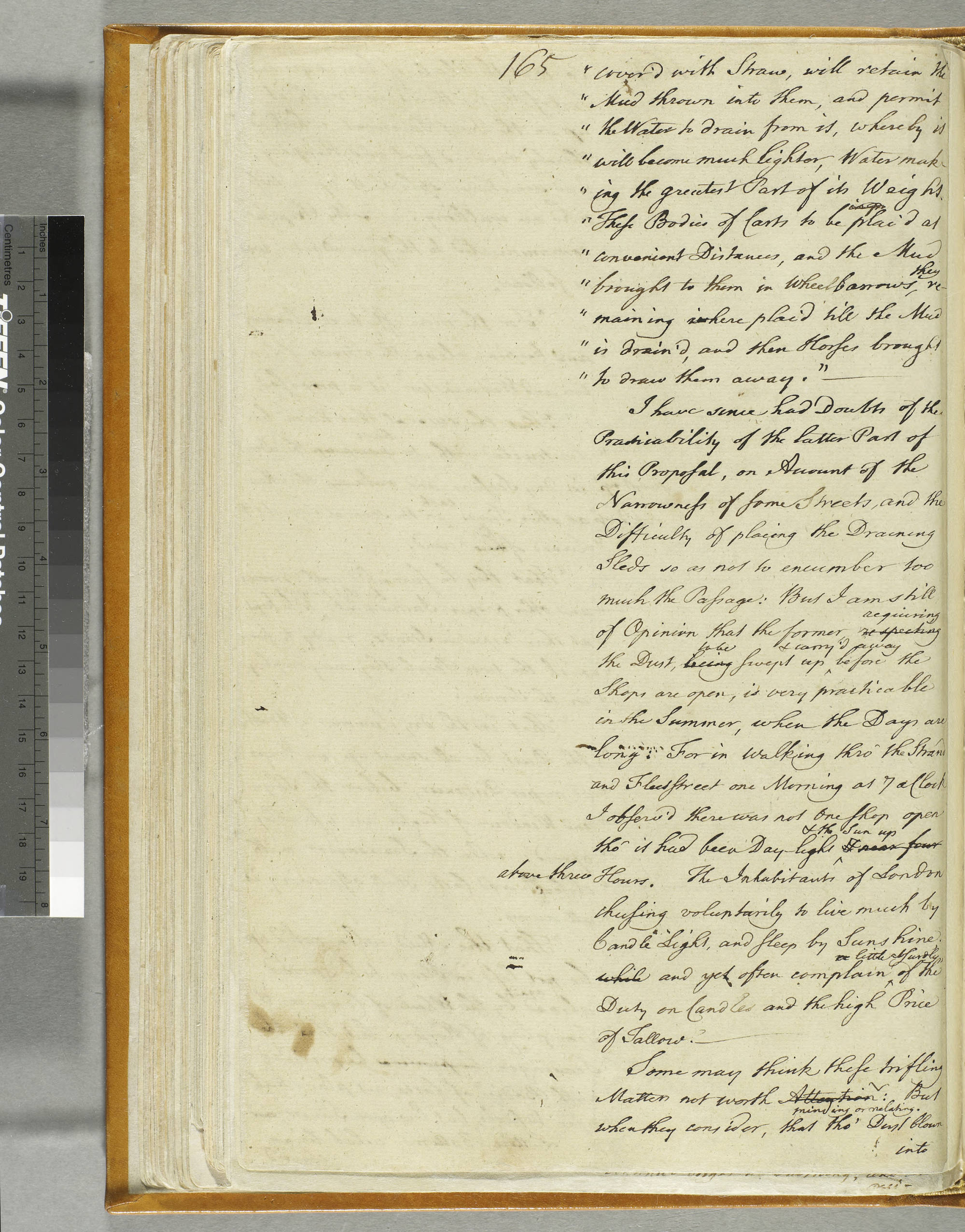

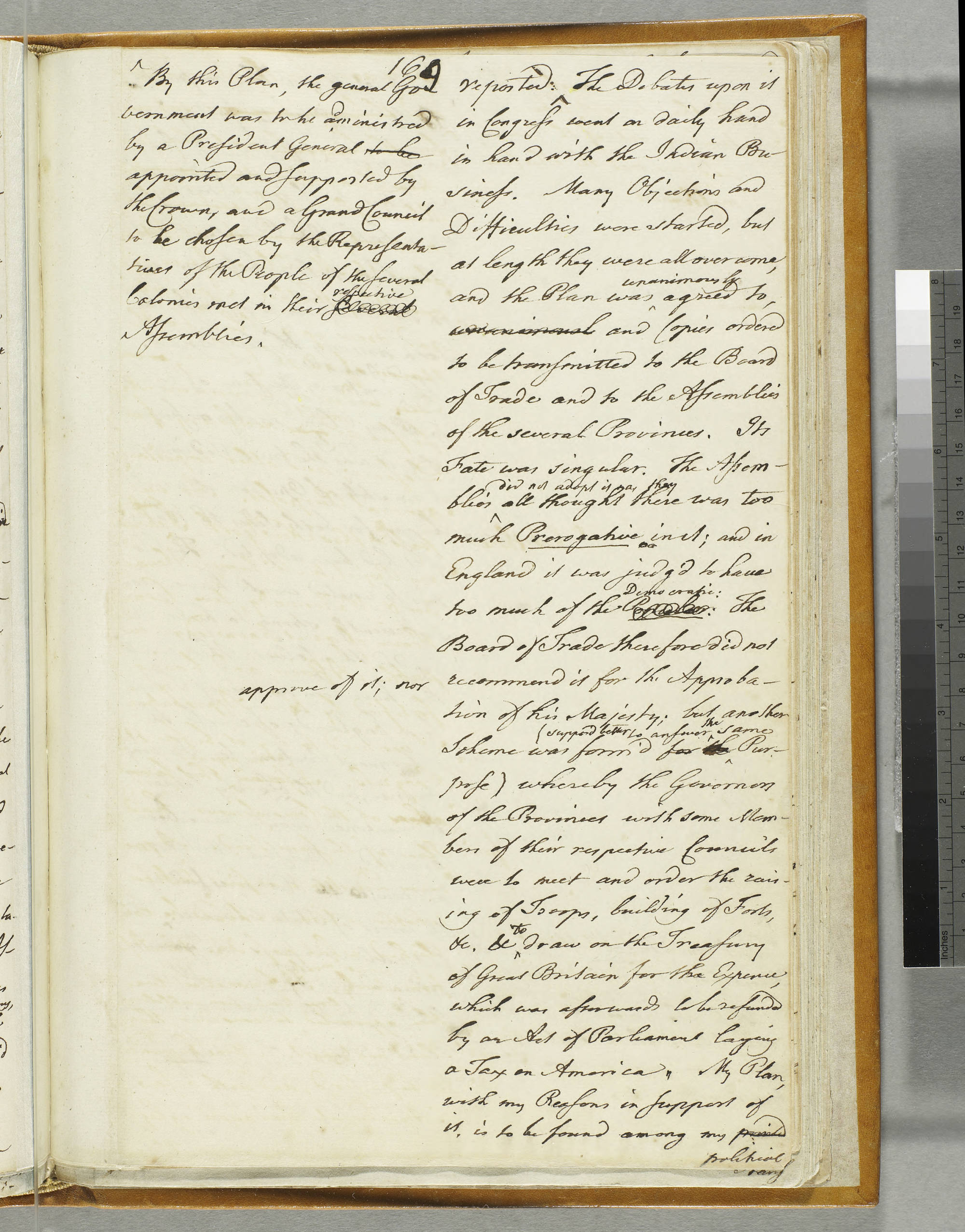

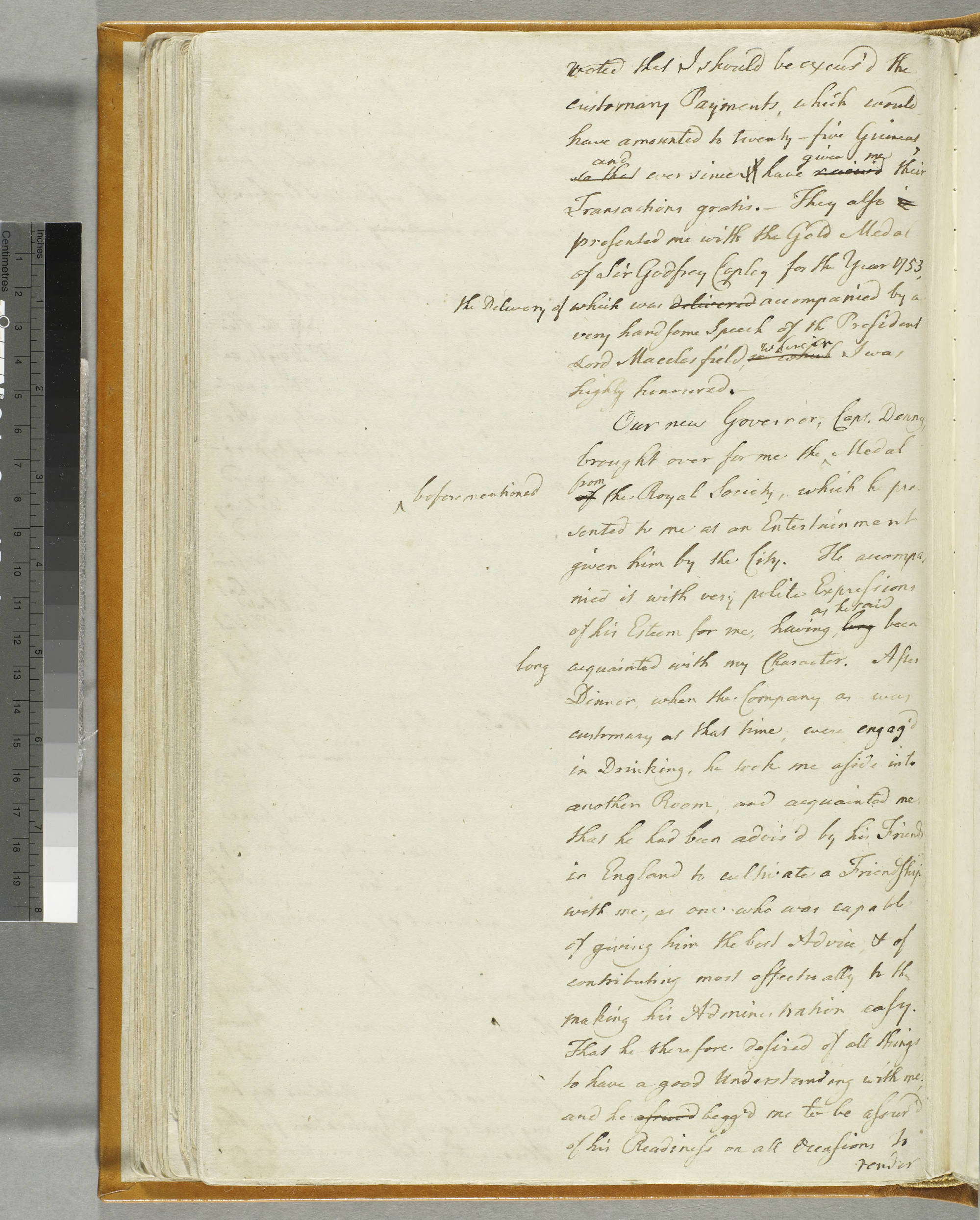

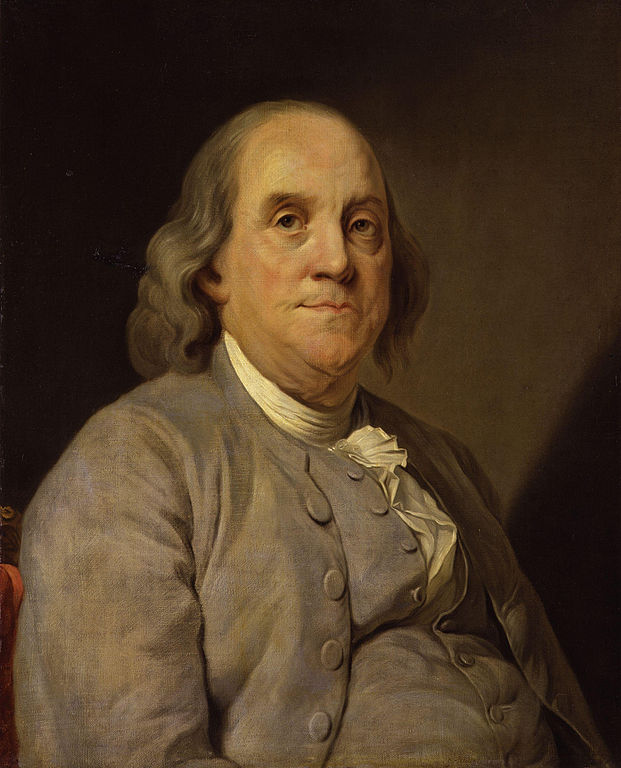

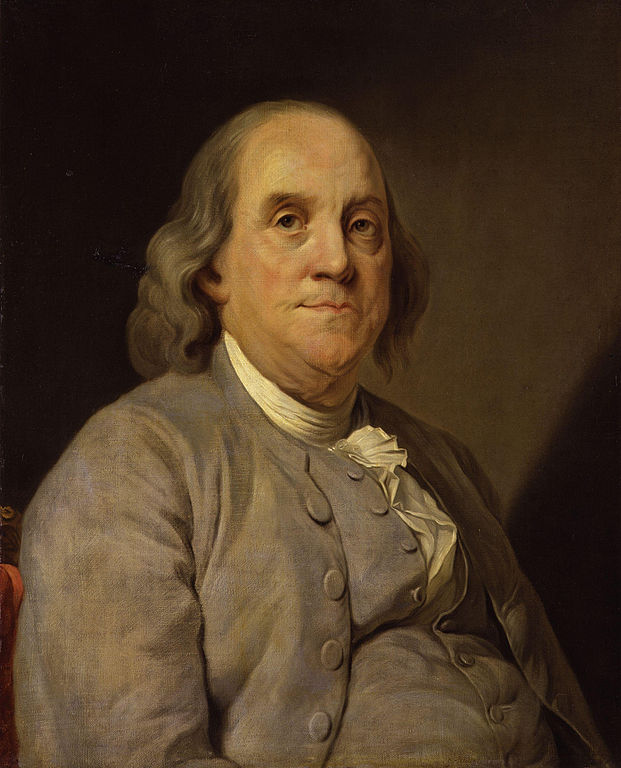

The book that we know as Benjamin Franklin's "Autobiography" was composed in several stages over more than two decades, and was never published in Franklin's lifetime. And Franklin's conception of what this book was and what its purposes should be changed over the years during which he was writing it. The first section was composed in the summer of 1771, when Franklin, then living in London and serving as the representative for several of the American colonies, was on an extended visit to the country home of his friend Jonathan Shipley. The text, which Franklin thought of as his "memoir" or his "life," takes the form of a letter to his son William. But it becomes clear very quickly that this was never a "letter" in the conventional sense, one intended to go through the post to its recipient. The later sections, composed in stages in the 1780s, seem addressed to a more general audience; as Franklin notes at the end of section one, he imagined that the first part contained "family Anecodotes of no Importance to others" but that latter parts of the text were "intended for the Public." This change in potential audience might been the result of Franklin's estrangement from his son in the intervening years, but also perhaps because Franklin saw this book as an opportunity to address a larger audience than he had originally planned.

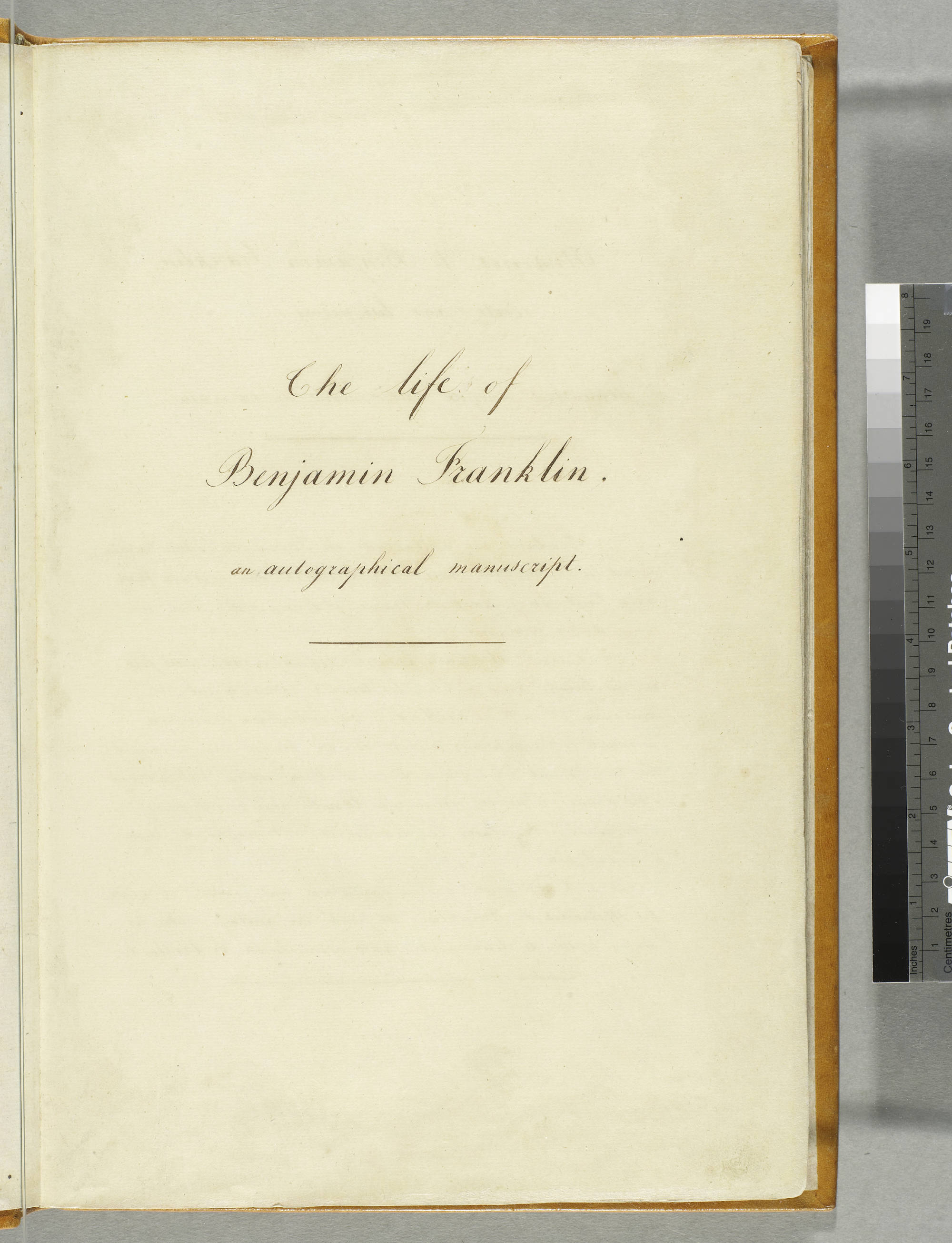

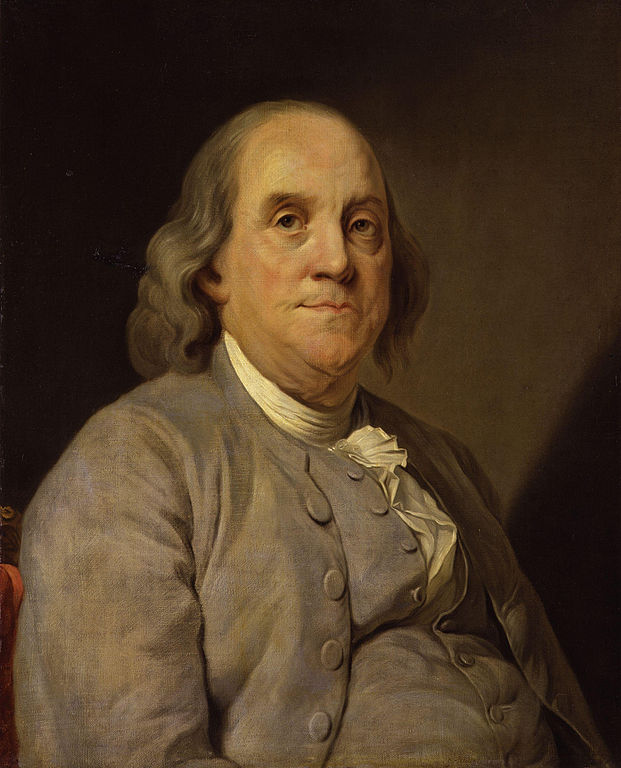

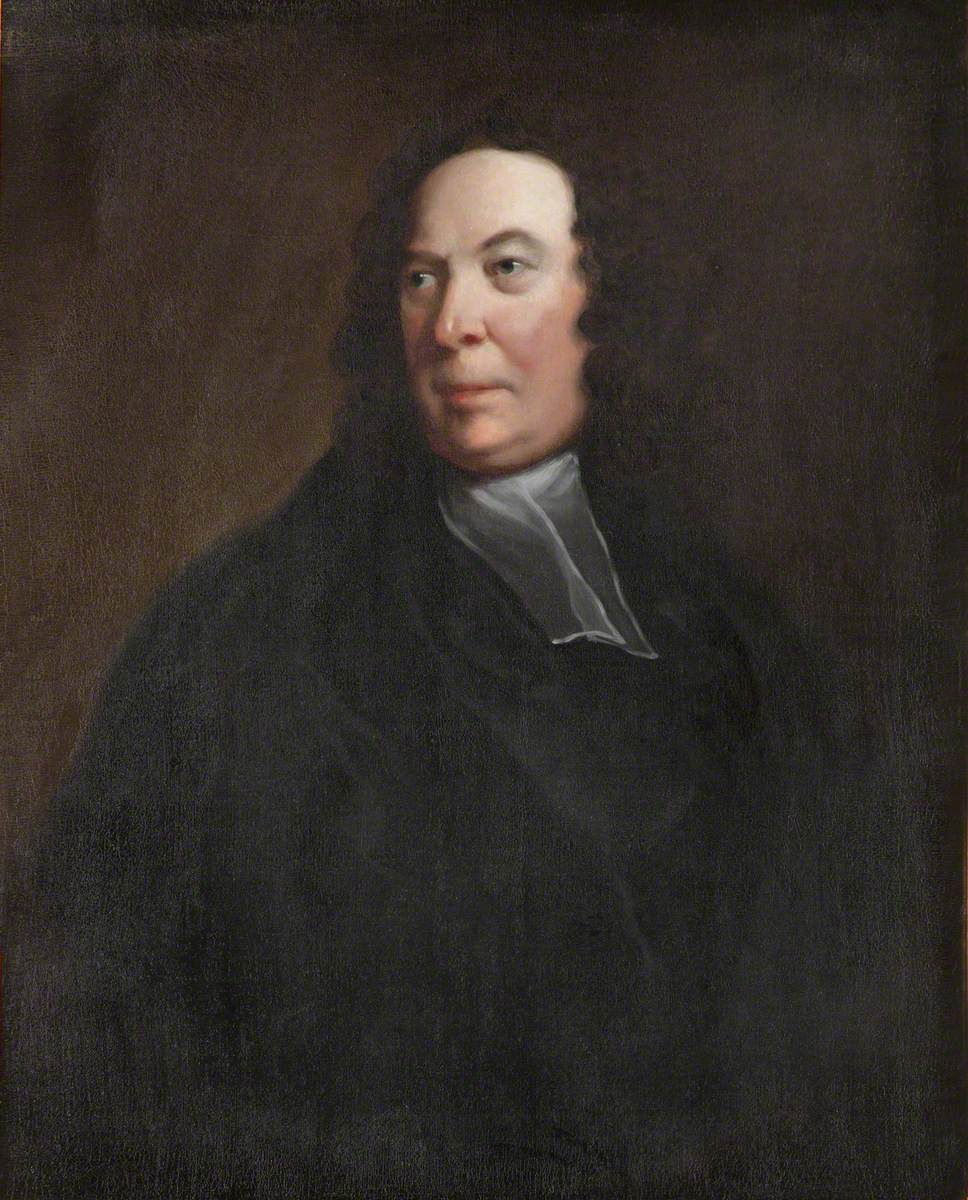

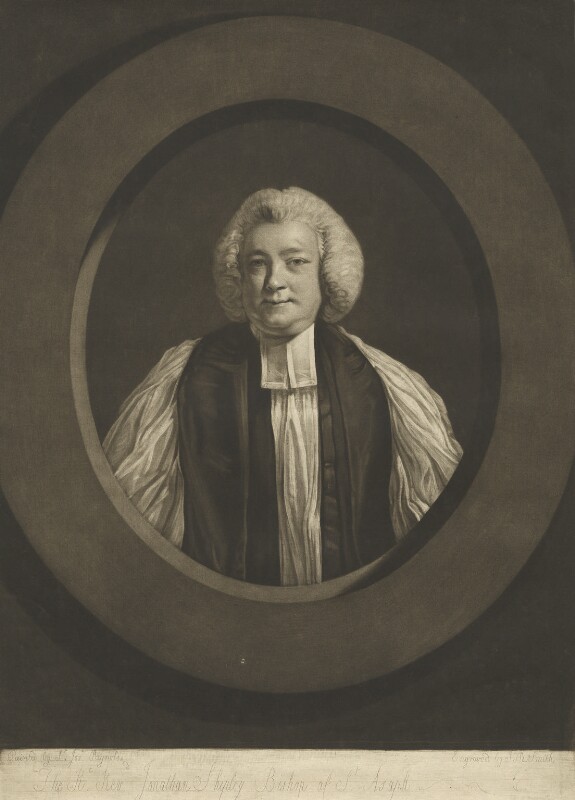

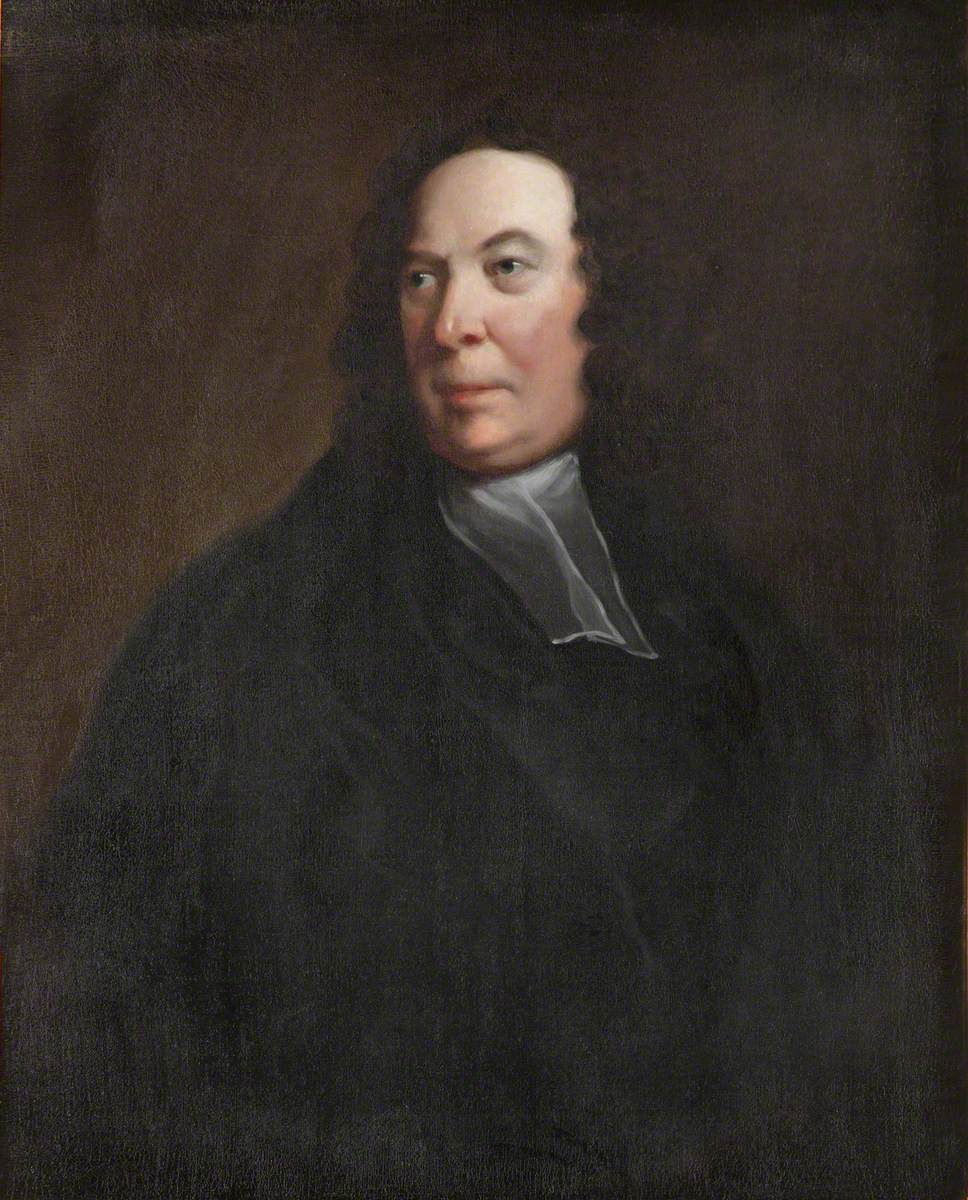

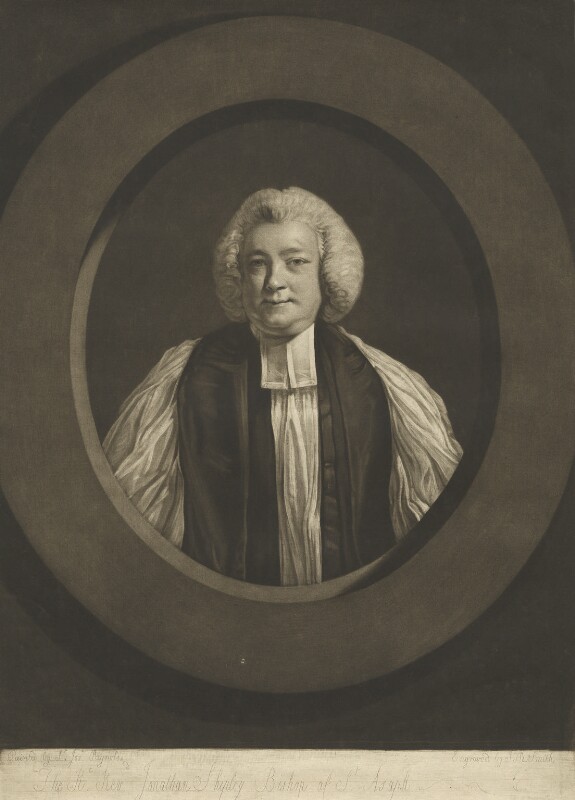

The manuscript, titled "The Life of Benjamin Franklin" by an unknown hand, is unfinished. Franklin picked up the manuscript in late 1789 and early 1790, but died before completing his memoir, which only goes up to the 1760s. How the manuscript was eventually published is a long and complicated story (at one point, the only edition available in English was one that had been re-translated from a French version), and it was not for several decades that the "Autobiography" assumed the form and the title that it now generally bears. But since the middle of the nineteenth century, this has been a landmark of American literature, and is certainly the best-known autobiography by any American. Our edition includes page images of the original manuscript, which is housed at the Huntington Library in California. We have edited the text to make it legible to modern reader, expanding abbreviations and regularizing the spelling and typography. Our annotations are designed to provide important contextual information that Franklin's first readers would have known. - [JOB]ShipleyJonathan Shipley (1714-1788) was the bishop of St. Asaph in Wales, but he spent much of his time at Twyford House, a large Tudor-era mansion in Hampshire in the south of England that had been in his family for generations. Shipley became a good friend and correspondent of Franklin's. He was sympathetic to the cause of the American colonists in their conflict with the government in London. Franklin wrote the first section of this memoir while he was visiting Shipley and his family at Twyford House for several weeks in July and August 1771.

The book that we know as Benjamin Franklin's "Autobiography" was composed in several stages over more than two decades, and was never published in Franklin's lifetime. And Franklin's conception of what this book was and what its purposes should be changed over the years during which he was writing it. The first section was composed in the summer of 1771, when Franklin, then living in London and serving as the representative for several of the American colonies, was on an extended visit to the country home of his friend Jonathan Shipley. The text, which Franklin thought of as his "memoir" or his "life," takes the form of a letter to his son William. But it becomes clear very quickly that this was never a "letter" in the conventional sense, one intended to go through the post to its recipient. The later sections, composed in stages in the 1780s, seem addressed to a more general audience; as Franklin notes at the end of section one, he imagined that the first part contained "family Anecodotes of no Importance to others" but that latter parts of the text were "intended for the Public." This change in potential audience might been the result of Franklin's estrangement from his son in the intervening years, but also perhaps because Franklin saw this book as an opportunity to address a larger audience than he had originally planned.

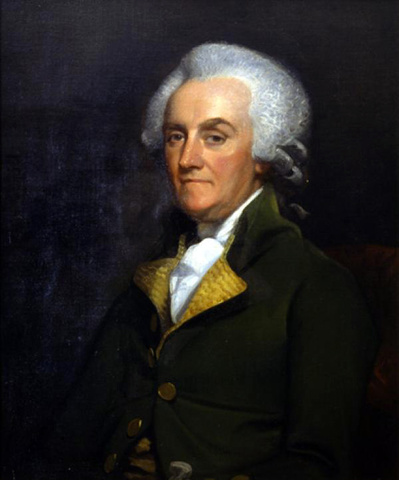

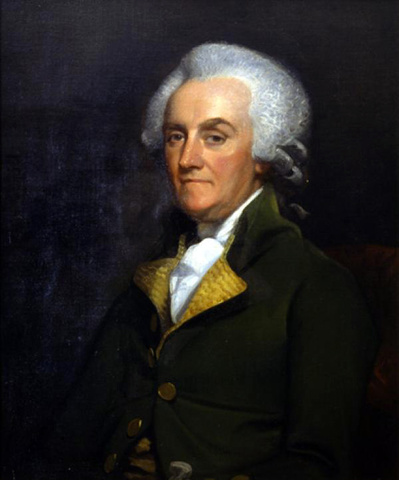

The manuscript, titled "The Life of Benjamin Franklin" by an unknown hand, is unfinished. Franklin picked up the manuscript in late 1789 and early 1790, but died before completing his memoir, which only goes up to the 1760s. How the manuscript was eventually published is a long and complicated story (at one point, the only edition available in English was one that had been re-translated from a French version), and it was not for several decades that the "Autobiography" assumed the form and the title that it now generally bears. But since the middle of the nineteenth century, this has been a landmark of American literature, and is certainly the best-known autobiography by any American. Our edition includes page images of the original manuscript, which is housed at the Huntington Library in California. We have edited the text to make it legible to modern reader, expanding abbreviations and regularizing the spelling and typography. Our annotations are designed to provide important contextual information that Franklin's first readers would have known. - [JOB]ShipleyJonathan Shipley (1714-1788) was the bishop of St. Asaph in Wales, but he spent much of his time at Twyford House, a large Tudor-era mansion in Hampshire in the south of England that had been in his family for generations. Shipley became a good friend and correspondent of Franklin's. He was sympathetic to the cause of the American colonists in their conflict with the government in London. Franklin wrote the first section of this memoir while he was visiting Shipley and his family at Twyford House for several weeks in July and August 1771.  - [UVAstudstaff]WilliamWilliam Franklin (c. 1730-1813) was Benjamin's Franklin's illegitimate son. His mother has never been identified with confidence; it might have been Franklin's common-law wife Deborah Read, but it also might have been another woman whose identity is lost to history. William worked with his father in London, when Benjamin Franklin was serving as the representative of several of the American colonies to the government in Westminster. In 1771, when this part of the narrative was written, William Franklin held the position of the royal governor of New Jersey. Father and son would soon be estranged over the American Revolutionary War; William remained loyal to the British crown and became a leading Loyalist opposing the American rebels. This of course included his father, who could not understand how his son could oppose him. William and Benjamin met a few times after the war, but never really reconciled.

- [UVAstudstaff]WilliamWilliam Franklin (c. 1730-1813) was Benjamin's Franklin's illegitimate son. His mother has never been identified with confidence; it might have been Franklin's common-law wife Deborah Read, but it also might have been another woman whose identity is lost to history. William worked with his father in London, when Benjamin Franklin was serving as the representative of several of the American colonies to the government in Westminster. In 1771, when this part of the narrative was written, William Franklin held the position of the royal governor of New Jersey. Father and son would soon be estranged over the American Revolutionary War; William remained loyal to the British crown and became a leading Loyalist opposing the American rebels. This of course included his father, who could not understand how his son could oppose him. William and Benjamin met a few times after the war, but never really reconciled.  - [UVAstudstaff]advantagesFranklin's figurative language wryly draws on his experience as a printer here and many times in the book, most obviously in his reflections on the "errata" or mistakes of his life, "errata" being a print-house term for a typographical error. - [UVAstudstaff]sinisterPrejudicial, adverse, unfavourable, darkly suspicious." (Source: Oxford English Dictionary) - [UVAstudstaff]franklinThe word "franklin" was a class signifier in England from the twelfth through the fifteenth centuries. A franklin was a free man ranking between the classes of serf and landed gentry. Franklins often owned land, but not enough to raise them anything close to the ranks of the gentry. The thirty acres that Benjamin Franklin describes as being owned by his ancestor was typical; it was enough of one's own land to survive, but not enough to become wealthy. For a classic literary example of a Franklin, see Geoffrey Chaucer's Franklin in The Canterbury Tales. - [UVAstudstaff]freehold"Permanent and absolute tenure of land or property with freedom to dispose of it at will." Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]scrivenerA person employed to copy or transcribe documents, or to write documenets on behalf of someone else; a scribe, a copyiest; a clerk, a secretary." Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]old-styleFor much of its history England used the Julian calendar (originally introduced by Julius Caesar in 46 B.C.) which became inaccurate over long periods of time. By the eighteenth century England was several days behind the rest of Europe, which used the Gregorian calendar. Britain switched over to the Gregorian calendar in 1752 A.D. by an act of Parliament, resulting in the "loss" of several dates. For this reason, Franklin had to celebrate his birthday on the 17th of January instead of the 6th, resulting in his need for a clarification of the date as in the "old style." - [UVAstudstaff]MSthat is, in manuscript - [UVAstudstaff]folio-quarto"Folio," "quarto," and "octavo" denote sizes of books, determined by the standard size of paper used in a print shop. A folio is a large volume where the paper is folded once; a quarto (sized at one-fourth the sheet) is half that size, and an octavo (where each page one-eighth of the sheet) is half the size of that. This would have been a very substantial collection of pamphlets. - [UVAstudstaff]against-poperyThe Franklin family's story, as told here, was typical of that of many English families, as their religious faith intersected with and was shaped by political events. By "early in the Reformation," Franklin makes cleaer that his family left the Roman Catholic Church (mocked by many as "popery") not long after Henry VIII separated from Rome in 1534, founding the Church of England. When Henry's daughter Mary became Queen in 1553, she returned England to the religious jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Church, and persecuted prominent Protestants. - [UVAstudstaff]English_BibleA Bible translated into English. The Roman church had preferred to use the Bible in Latin, but after the Reformation, there was a new emphasis on individuals being able to read the Bible for themselves, and a spate of translations into English emerged, such as the one done by William Tyndale and Miles Coverdale, available by the late 1530s; the Franklin family Bible might have been this edition. - [UVAstudstaff]non-conformityNon-conformity: Refusal to conform to the doctrine, discipline, or usages of the Church of England, or of any established church, etc.; the principles or practice of nonconformists. Now usually: Protestant dissent; the body of nonconformists or nonconformist opinion. Conventicle: A meeting of (Protestant) Nonconformists or Dissenters from the Church of England for religious worship, during the period when such meetings were prohibited by the law. Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]FolgerPeter Folger (1617-1690): Folger, born in Norwich, migrated to Massachusetts in 1635. He learned the Algonquian language and became an interpreter and “intermediary with the American Indian population” on the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. He also worked other jobs such as teacher, surveyor, farmer, and clerk of courts. His was a prominent family that produced “American scientists, merchants, and politicians, the most famous of whom was Benjamin Franklin, Folger’s grandson.” Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography - [UVAstudstaff]MatherCotton Mather, born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1663 to one of the city's most influential families, became arguably the most prominent minister in the American colonies.

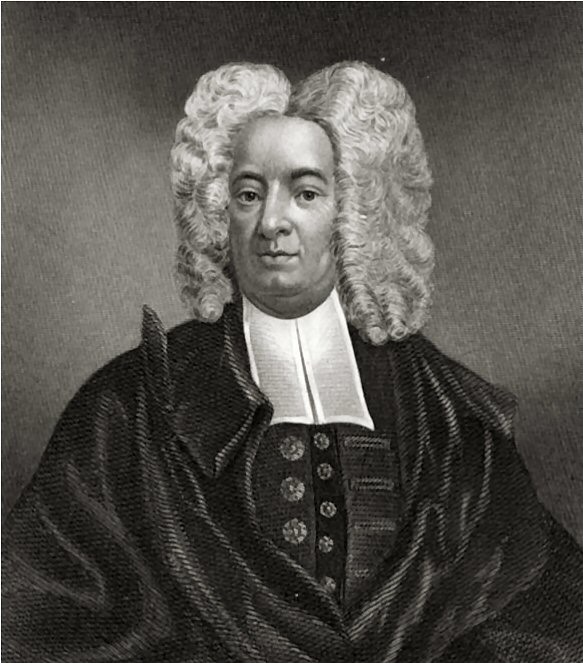

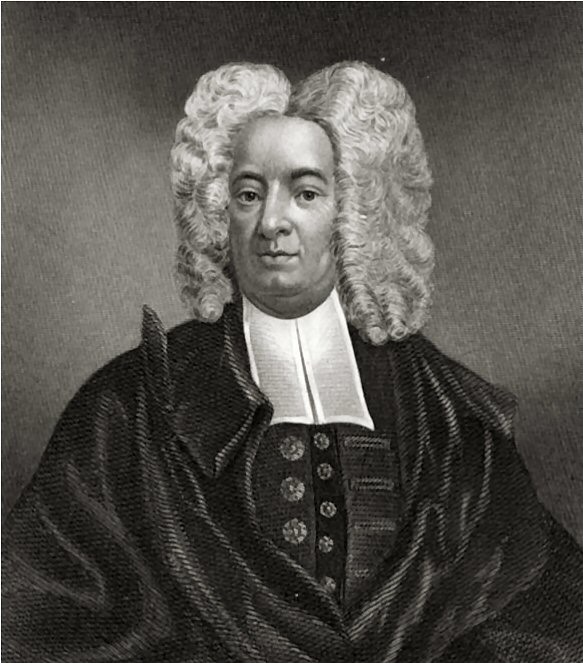

- [UVAstudstaff]advantagesFranklin's figurative language wryly draws on his experience as a printer here and many times in the book, most obviously in his reflections on the "errata" or mistakes of his life, "errata" being a print-house term for a typographical error. - [UVAstudstaff]sinisterPrejudicial, adverse, unfavourable, darkly suspicious." (Source: Oxford English Dictionary) - [UVAstudstaff]franklinThe word "franklin" was a class signifier in England from the twelfth through the fifteenth centuries. A franklin was a free man ranking between the classes of serf and landed gentry. Franklins often owned land, but not enough to raise them anything close to the ranks of the gentry. The thirty acres that Benjamin Franklin describes as being owned by his ancestor was typical; it was enough of one's own land to survive, but not enough to become wealthy. For a classic literary example of a Franklin, see Geoffrey Chaucer's Franklin in The Canterbury Tales. - [UVAstudstaff]freehold"Permanent and absolute tenure of land or property with freedom to dispose of it at will." Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]scrivenerA person employed to copy or transcribe documents, or to write documenets on behalf of someone else; a scribe, a copyiest; a clerk, a secretary." Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]old-styleFor much of its history England used the Julian calendar (originally introduced by Julius Caesar in 46 B.C.) which became inaccurate over long periods of time. By the eighteenth century England was several days behind the rest of Europe, which used the Gregorian calendar. Britain switched over to the Gregorian calendar in 1752 A.D. by an act of Parliament, resulting in the "loss" of several dates. For this reason, Franklin had to celebrate his birthday on the 17th of January instead of the 6th, resulting in his need for a clarification of the date as in the "old style." - [UVAstudstaff]MSthat is, in manuscript - [UVAstudstaff]folio-quarto"Folio," "quarto," and "octavo" denote sizes of books, determined by the standard size of paper used in a print shop. A folio is a large volume where the paper is folded once; a quarto (sized at one-fourth the sheet) is half that size, and an octavo (where each page one-eighth of the sheet) is half the size of that. This would have been a very substantial collection of pamphlets. - [UVAstudstaff]against-poperyThe Franklin family's story, as told here, was typical of that of many English families, as their religious faith intersected with and was shaped by political events. By "early in the Reformation," Franklin makes cleaer that his family left the Roman Catholic Church (mocked by many as "popery") not long after Henry VIII separated from Rome in 1534, founding the Church of England. When Henry's daughter Mary became Queen in 1553, she returned England to the religious jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Church, and persecuted prominent Protestants. - [UVAstudstaff]English_BibleA Bible translated into English. The Roman church had preferred to use the Bible in Latin, but after the Reformation, there was a new emphasis on individuals being able to read the Bible for themselves, and a spate of translations into English emerged, such as the one done by William Tyndale and Miles Coverdale, available by the late 1530s; the Franklin family Bible might have been this edition. - [UVAstudstaff]non-conformityNon-conformity: Refusal to conform to the doctrine, discipline, or usages of the Church of England, or of any established church, etc.; the principles or practice of nonconformists. Now usually: Protestant dissent; the body of nonconformists or nonconformist opinion. Conventicle: A meeting of (Protestant) Nonconformists or Dissenters from the Church of England for religious worship, during the period when such meetings were prohibited by the law. Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]FolgerPeter Folger (1617-1690): Folger, born in Norwich, migrated to Massachusetts in 1635. He learned the Algonquian language and became an interpreter and “intermediary with the American Indian population” on the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. He also worked other jobs such as teacher, surveyor, farmer, and clerk of courts. His was a prominent family that produced “American scientists, merchants, and politicians, the most famous of whom was Benjamin Franklin, Folger’s grandson.” Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography - [UVAstudstaff]MatherCotton Mather, born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1663 to one of the city's most influential families, became arguably the most prominent minister in the American colonies.  Indeed, his influence was so widely felt he could be described as one of the major transatlantic figures of the time. Ordained at Boston's North Church, he served there as minister for the entirety of his career. However, Mather's influence was not only limited to religion. He was politically active, and he studied science as well, eventually gaining admittance to London's Royal Society.

A prolific author, he published approximately 380 texts, including Magnalia Christi Americana (on the movement of Christianity from Europe to America) and Bonifacius, Essays to do Good. By the end of his life, Mather’s influence on Christianity in the colonies laid the groundwork for religious figures such as Jonathan Edwards. Mather died in February 1728 at the age of 65.

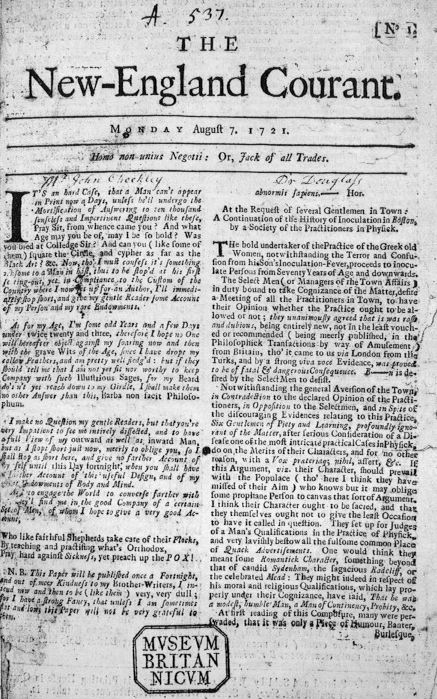

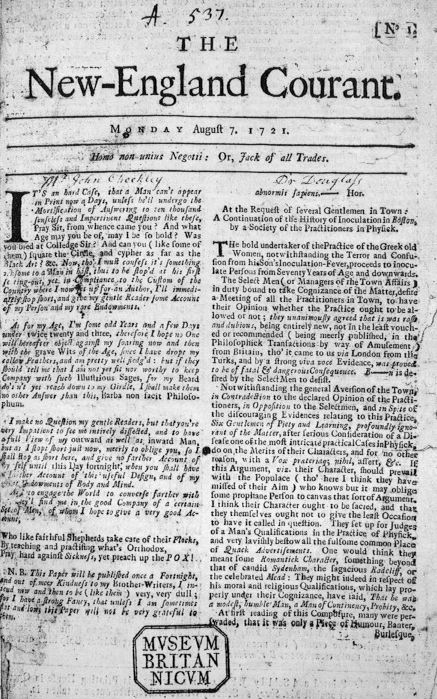

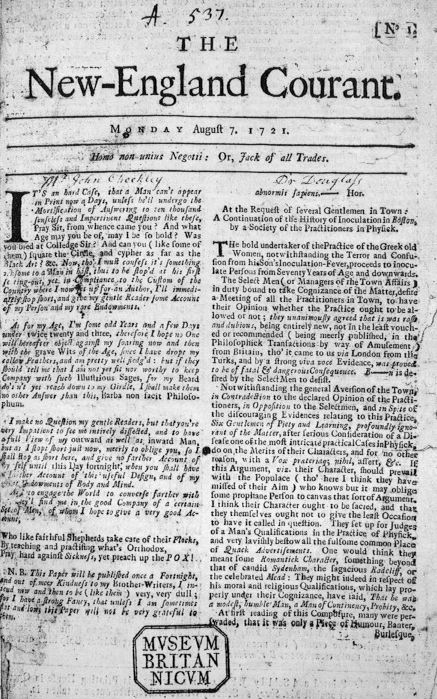

Mather’s works were wide-reaching, so it is unsurprising that Franklin felt his influence—most notably through Mather’s Essays to do Good. While working as an apprentice in his brother’s print shop in 1722, sixteen-year-old Franklin wrote essays under the pseudonym of Silence Dogood—the surname "Dogood" was surely taken directly from Mather’s title. The persona Franklin assumed as Silence Dogood was a middle-aged minister’s widow who wrote on a variety of social topics such as politics, fashion, and education. Franklin silently slid these essays under the door of his brother’s business, hoping for publication. His ploy worked, and Franklin's pseudonymous works were published until October of 1722. Some critics have suggested that the the pseudonym and some of the essays were actually a mockery of Mather since the initial run of essays from Silence Dogood appeared at approximately the same time as widespread debates surrounding inoculation, a practice opposed by James Franklin, Benjamin’s brother and owner of The New England Courant.

For his part, Mather was a strong proponent of inoculation to the extent that in 1721, Mather and Dr. Zabdiel Boylston inoculated over 200 people during a smallpox epidemic, in the process eliciting a certain amount of public outcry. At the same time, James Franklin published numerous articles against inoculation in the Courant. Years later, and after his own child contracted smallpox, Franklin changed his position on inoculation, regretting his failure to inoculate his son.

Though Mather and Benjamin Franklin held opposing views upon various matters, there is no doubt that Mather exerted major influence upon Franklin. For instance, Essays to do Good provides practical tips for how to “do good” for the “Saviour, and for His People in the world.” The book is short and easily read, and its practicality and warmth made it popular throughout the colonies and in England. Franklin appears to have extrapolated not only the form, but the ethical substance from the book, publishing his own Poor Richard's Almanac, an annual journal consisting of practical tips, witty sayings, and household advice. In the Autobiography, he notes that his father’s library held a copy of Mather's book, and that reading it “perhaps gave me a Turn of Thinking that had an Influence on some of the principal future Events of my Life.” In a letter written to Mather’s son Samuel in 1773, Franklin acknowledged Mather’s influence: "When I was a boy, I met with a book, entitled “Essays to do good,” which, I think, was written by your father. It had been so little regarded by a former possessor, that several leaves of it were torn out: but the remainder gave me such a turn, for thinking, as to have an influence on my conduct through life; for I have always set a greater value on the character of a doer of good, than any other kind of reputation; and if I have been, as you seem to think, a useful citizen, the public owes the advantage of it to that book." - [UVAstudstaff]schoolUnder the system of primogeniture that governed the inheritance of property in the landowning classes of Anglo-America, only the oldest son could inherit his father's land. Because of this, the younger sons were often sent off to practice law, join the military, or become ministers in the church. This trend extended into the middle class as well, as often the younger sons were sent, as here, as a "tithe" to the church for both religious and practical reasons. - [UVAstudstaff]BrownellBrownell was born in London and arrived in the North American colonies around 1703. By 1712 he and his wife were running a boarding school for boys in Boston. Franklin attended Brownell's school from 1715 to 1716, at which point the cost apparently became too great for his family to sustain. - [UVAstudstaff]seaSons leaving home for adventure and quick profit was a common trope in the literature of this period due to the increase in England's colonial presence throughout the century. Robinson Crusoe presents one such example, but the ocean as a metaphor for both empire and capitalist gains was present in many eighteenth century stories. - [UVAstudstaff]emmetsants. Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]Burton"Richard Burton" or "RB" were pseudonyms for Nathaniel Crouch (c. 1632-1725), who published dozens of popular histories in the second half of the 1600s, books that went through many editions. Most of these were pretty much plagiarized from the works of other writers, but many readers, like the young Franklin, learned a good deal of history through his inexpensive digests of longer works. - [UVAstudstaff]DefoeDaniel Defoe's An Essay upon Projects, published in 1697, outlines a number of plans for organizing associations to improve English society, including special courts for merchants and an early form of life insurance. - [UVAstudstaff]EssaysAs noted above, Mather was an important influence on Franklin whose persona of "Silence Dogood" in his first published essays allude to the title of Mather's book. - [UVAstudstaff]twenty-one-years-of-ageIt is worth noting that this is an unusually long apprenticeship; most apprenticeships were for seven rather than nine years. We do not know why Benjamin's apprenticeship was stipulated to be that long. The provision that he get "journeyman's wages," that is, the salary of a flully-fledged printer, might have been offered as a compromise.

The fact of Franklin's apprenticeship, and his early departure from his brother's ship, which is coming up in in a few pages, informs much of this early part of the narrative. During his trip from Boston to Philadelphia Franklin recounts being wary about attracting attention, noting, “it seemed to be suspected from my youth and appearance, that I might be some runaway.” This statement seems odd, considering Franklin technically was a runaway—he had left his apprenticeship with his brother against the will of the family. Why did Franklin not consider himself classed with other young runaways, when he did fear being mistaken for one and returned to Boston? He certainly had run away from Boston, knowing that if he left openly, “means would be used to prevent [him].” Yet Franklin was in a somewhat unique position: he had technically run away without his brother’s permission, yet he knew that he would not be treated as a common runaway apprentice.

Apprenticeship in the American colonies had its roots in the practices of the English system, which dates back to the middle ages. One of the major pieces of legislation governing apprenticeship was the English Statute of Artificers (1563), which required parents who did not otherwise provide for the education of their sons to bind them to a trade or the agricultural system. The seven year term, longer than the normal length of apprenticeship in France and Germany, “was designed to ensure English supremacy in handmade manufactures and to discourage the wandering and strolling that had characterized earlier periods of English life.” Another aspect of English law and custom that influenced apprenticeship in the colonies was the English Poor Law (1601) which required local authorities to bind poor or orphaned children into apprenticeship if their parents did not do so. Benjamin Franklin belonged to the class of apprentices who bound themselves “by their own free will and consent” to a master to learn his trade, not the apprentices involuntarily bound under the auspices of the Poor Law.

These English statutes applied to the American colonies in theory. However, these laws and customs depended on the medieval guild system for enforcement—a system which never developed in the colonies. Eighteenth-century colonial America did not have the deep pool of skilled laborers that characterized the guild system and had no enforcement mechanism to monitor quality of work, admit members to the status of journeyman or master, or standardize apprentice training. In the colonies, “anyone could call himself a master artisan, and any such artisan could take an apprentice”—or many apprentices at once. During Franklin’s boyhood in Boston, the real wages of artisans were falling and apprenticeship contracts often did not demand fees from parents, except for those in high-status crafts. It was guild enforcement that kept wages high and ensured quality craft in the English system, because it created a closed labor market—no artisan could work without permission from his guild.

In England, if an apprentice ran away from his master, there was an ironclad system in place to keep him from practicing his craft anywhere in the country. The guild system ensured that jurisdiction rules were enforced, and any new practitioner would have to be an approved guild member. In America, runaway penalties did not extend beyond the borders of each colony, and, as Franklin’s narrative attests, the demand for skilled labor meant even a partially-trained apprentice would likely be hired, perhaps even with the status of a journeyman (though this label did not hold the weight it would in England). If an American apprentice ran away, his master would circulate a description of the runaway with an offer of reward, and if returned, the apprentice would have to serve for a longer period. The reward was the enforcement mechanism, meaning citizens might be on the lookout for apparent runaways.

Technically, to be legal, an apprenticeship contract (called an “indenture”) had to be registered with municipal authorities so it could be used as evidence in case of disputes. This was true even in the colonies. However, the nature of indenture papers meant that possession of one’s half of the contract should have constituted evidence without consulting town records: “indenture” papers were indented on both halves of the document so they could later be identified as one contract. Benjamin Franklin’s original contract with his brother would probably have been properly registered—but the second set of indentures, which were secret, would only have been held by the master and the apprentice. James probably could have proved that Benjamin was his apprentice by comparing the two halves of the indenture, but once his brother was out of Boston, this means of redress was impractical at best. And of course, in attempting to regain his apprentice, James would have had to admit his real ownership of the Courant. - [UVAstudstaff]wretched-stuffNeither of these poems has survived. But what Franklin was doing was a fairly typical thing in this period; newspapers were often filled with poems about recent events, particularly events as notable and spectacular as the two mentioned here. The death by drowning of George Worthilake, his wife and daughter (Franklin misremembers this as having been two daughters) as they were returning from church by boat to the lighthouse that Worthilake was in charge of in Novenber 1716 became known as the "Lighthouse Tragedy." Edward Teach, the pirate known as Blackbeard, was killed in a firefight with ships from the Royal Navy off the coast of North Carolina on November 22, 1718. The "Grub Street-ballad-style" that Franklin laments using here was nothing to be ashamed of; many authors in this period wrote popular ballads published in the kind of popular journals that became associated with "Grub Street," the physical home of mass market printing in London. - [UVAstudstaff]pointingpunctuation - [UVAstudstaff]SpectatorThe Spectator was a newspaper created by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele that ran from March 3, 1711 to December 6, 1712. It consisted of a series of essays that were for the most part written by either Steele or Addison, but they assumed the viewpoint of the persona of “Mr. Spectator.” “Mr. Spectator” was a quiet observer of English society who commented on politics, fashion, and social issues through these essays, which were widely popular in both England and the colonies. They were read as models of good English style, and also as guides for civilized, middle-class behavior. Benjamin Franklin was influenced by Spectator's prose style. And the persona of "Silence Dogood" that he would use in his own periodical essays was clearly influenced by the silent "Mr. Spectator" of Addison and Steele's influential journal. - [UVAstudstaff]third

Given Franklin's later interest in public finance, it is striking to see that the particular essay of the Spectatorthat he remembers as his introduction to the series is a famous piece by Addison on the topic of "public credit." - [UVAstudstaff]vegetableThomas Tryon's The Way to Health, Long Life, and Happiness,

Indeed, his influence was so widely felt he could be described as one of the major transatlantic figures of the time. Ordained at Boston's North Church, he served there as minister for the entirety of his career. However, Mather's influence was not only limited to religion. He was politically active, and he studied science as well, eventually gaining admittance to London's Royal Society.

A prolific author, he published approximately 380 texts, including Magnalia Christi Americana (on the movement of Christianity from Europe to America) and Bonifacius, Essays to do Good. By the end of his life, Mather’s influence on Christianity in the colonies laid the groundwork for religious figures such as Jonathan Edwards. Mather died in February 1728 at the age of 65.

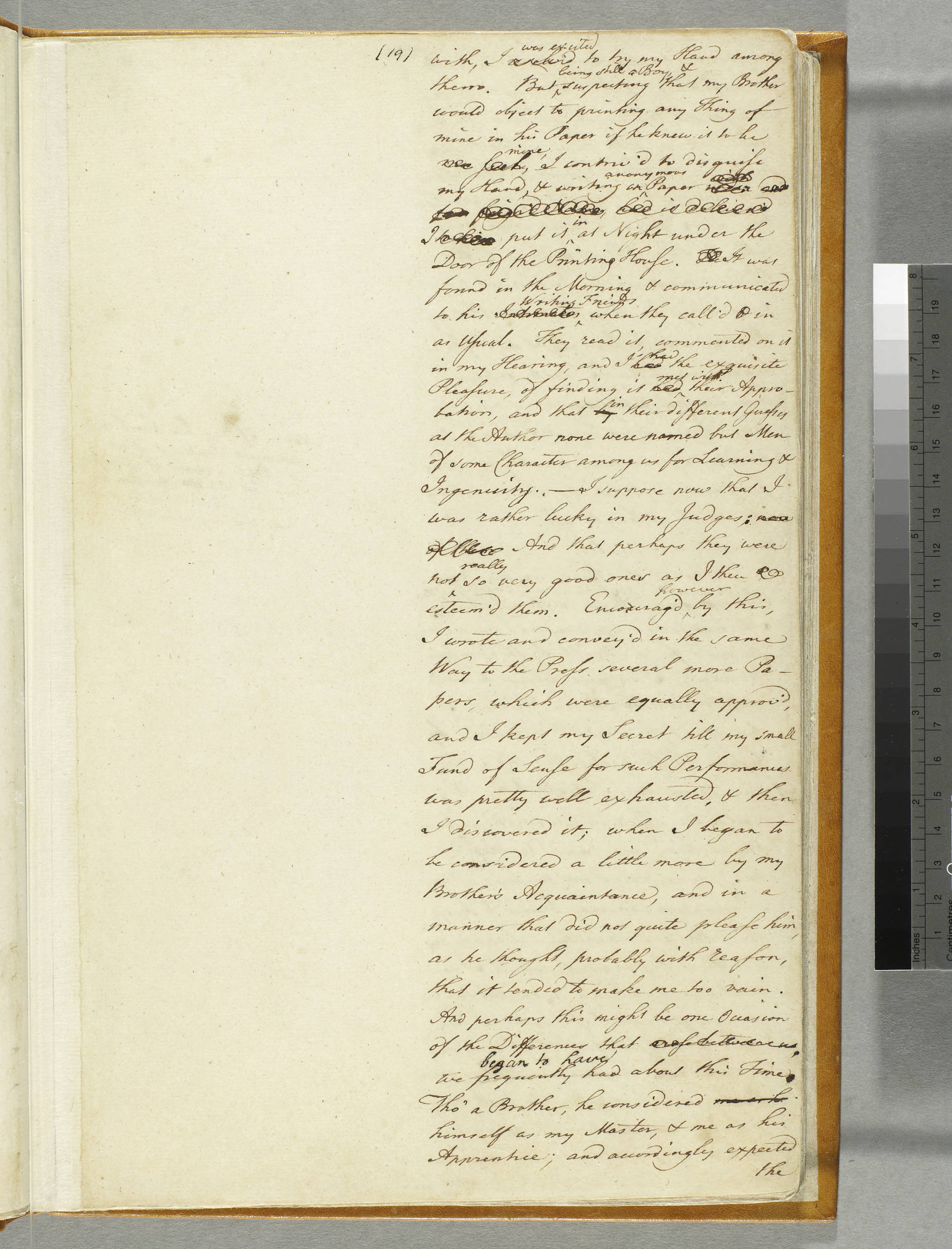

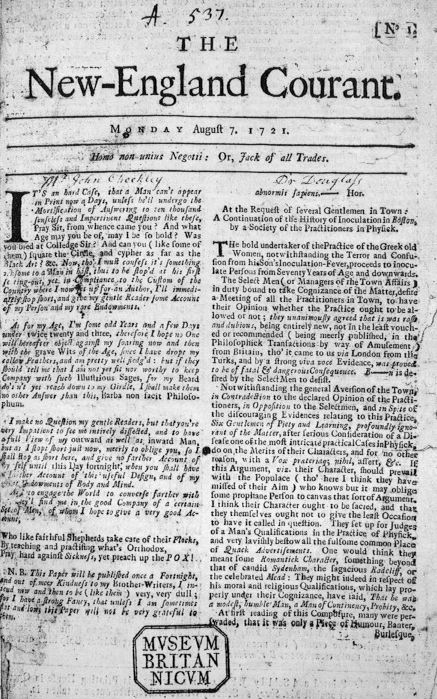

Mather’s works were wide-reaching, so it is unsurprising that Franklin felt his influence—most notably through Mather’s Essays to do Good. While working as an apprentice in his brother’s print shop in 1722, sixteen-year-old Franklin wrote essays under the pseudonym of Silence Dogood—the surname "Dogood" was surely taken directly from Mather’s title. The persona Franklin assumed as Silence Dogood was a middle-aged minister’s widow who wrote on a variety of social topics such as politics, fashion, and education. Franklin silently slid these essays under the door of his brother’s business, hoping for publication. His ploy worked, and Franklin's pseudonymous works were published until October of 1722. Some critics have suggested that the the pseudonym and some of the essays were actually a mockery of Mather since the initial run of essays from Silence Dogood appeared at approximately the same time as widespread debates surrounding inoculation, a practice opposed by James Franklin, Benjamin’s brother and owner of The New England Courant.

For his part, Mather was a strong proponent of inoculation to the extent that in 1721, Mather and Dr. Zabdiel Boylston inoculated over 200 people during a smallpox epidemic, in the process eliciting a certain amount of public outcry. At the same time, James Franklin published numerous articles against inoculation in the Courant. Years later, and after his own child contracted smallpox, Franklin changed his position on inoculation, regretting his failure to inoculate his son.

Though Mather and Benjamin Franklin held opposing views upon various matters, there is no doubt that Mather exerted major influence upon Franklin. For instance, Essays to do Good provides practical tips for how to “do good” for the “Saviour, and for His People in the world.” The book is short and easily read, and its practicality and warmth made it popular throughout the colonies and in England. Franklin appears to have extrapolated not only the form, but the ethical substance from the book, publishing his own Poor Richard's Almanac, an annual journal consisting of practical tips, witty sayings, and household advice. In the Autobiography, he notes that his father’s library held a copy of Mather's book, and that reading it “perhaps gave me a Turn of Thinking that had an Influence on some of the principal future Events of my Life.” In a letter written to Mather’s son Samuel in 1773, Franklin acknowledged Mather’s influence: "When I was a boy, I met with a book, entitled “Essays to do good,” which, I think, was written by your father. It had been so little regarded by a former possessor, that several leaves of it were torn out: but the remainder gave me such a turn, for thinking, as to have an influence on my conduct through life; for I have always set a greater value on the character of a doer of good, than any other kind of reputation; and if I have been, as you seem to think, a useful citizen, the public owes the advantage of it to that book." - [UVAstudstaff]schoolUnder the system of primogeniture that governed the inheritance of property in the landowning classes of Anglo-America, only the oldest son could inherit his father's land. Because of this, the younger sons were often sent off to practice law, join the military, or become ministers in the church. This trend extended into the middle class as well, as often the younger sons were sent, as here, as a "tithe" to the church for both religious and practical reasons. - [UVAstudstaff]BrownellBrownell was born in London and arrived in the North American colonies around 1703. By 1712 he and his wife were running a boarding school for boys in Boston. Franklin attended Brownell's school from 1715 to 1716, at which point the cost apparently became too great for his family to sustain. - [UVAstudstaff]seaSons leaving home for adventure and quick profit was a common trope in the literature of this period due to the increase in England's colonial presence throughout the century. Robinson Crusoe presents one such example, but the ocean as a metaphor for both empire and capitalist gains was present in many eighteenth century stories. - [UVAstudstaff]emmetsants. Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]Burton"Richard Burton" or "RB" were pseudonyms for Nathaniel Crouch (c. 1632-1725), who published dozens of popular histories in the second half of the 1600s, books that went through many editions. Most of these were pretty much plagiarized from the works of other writers, but many readers, like the young Franklin, learned a good deal of history through his inexpensive digests of longer works. - [UVAstudstaff]DefoeDaniel Defoe's An Essay upon Projects, published in 1697, outlines a number of plans for organizing associations to improve English society, including special courts for merchants and an early form of life insurance. - [UVAstudstaff]EssaysAs noted above, Mather was an important influence on Franklin whose persona of "Silence Dogood" in his first published essays allude to the title of Mather's book. - [UVAstudstaff]twenty-one-years-of-ageIt is worth noting that this is an unusually long apprenticeship; most apprenticeships were for seven rather than nine years. We do not know why Benjamin's apprenticeship was stipulated to be that long. The provision that he get "journeyman's wages," that is, the salary of a flully-fledged printer, might have been offered as a compromise.

The fact of Franklin's apprenticeship, and his early departure from his brother's ship, which is coming up in in a few pages, informs much of this early part of the narrative. During his trip from Boston to Philadelphia Franklin recounts being wary about attracting attention, noting, “it seemed to be suspected from my youth and appearance, that I might be some runaway.” This statement seems odd, considering Franklin technically was a runaway—he had left his apprenticeship with his brother against the will of the family. Why did Franklin not consider himself classed with other young runaways, when he did fear being mistaken for one and returned to Boston? He certainly had run away from Boston, knowing that if he left openly, “means would be used to prevent [him].” Yet Franklin was in a somewhat unique position: he had technically run away without his brother’s permission, yet he knew that he would not be treated as a common runaway apprentice.

Apprenticeship in the American colonies had its roots in the practices of the English system, which dates back to the middle ages. One of the major pieces of legislation governing apprenticeship was the English Statute of Artificers (1563), which required parents who did not otherwise provide for the education of their sons to bind them to a trade or the agricultural system. The seven year term, longer than the normal length of apprenticeship in France and Germany, “was designed to ensure English supremacy in handmade manufactures and to discourage the wandering and strolling that had characterized earlier periods of English life.” Another aspect of English law and custom that influenced apprenticeship in the colonies was the English Poor Law (1601) which required local authorities to bind poor or orphaned children into apprenticeship if their parents did not do so. Benjamin Franklin belonged to the class of apprentices who bound themselves “by their own free will and consent” to a master to learn his trade, not the apprentices involuntarily bound under the auspices of the Poor Law.

These English statutes applied to the American colonies in theory. However, these laws and customs depended on the medieval guild system for enforcement—a system which never developed in the colonies. Eighteenth-century colonial America did not have the deep pool of skilled laborers that characterized the guild system and had no enforcement mechanism to monitor quality of work, admit members to the status of journeyman or master, or standardize apprentice training. In the colonies, “anyone could call himself a master artisan, and any such artisan could take an apprentice”—or many apprentices at once. During Franklin’s boyhood in Boston, the real wages of artisans were falling and apprenticeship contracts often did not demand fees from parents, except for those in high-status crafts. It was guild enforcement that kept wages high and ensured quality craft in the English system, because it created a closed labor market—no artisan could work without permission from his guild.

In England, if an apprentice ran away from his master, there was an ironclad system in place to keep him from practicing his craft anywhere in the country. The guild system ensured that jurisdiction rules were enforced, and any new practitioner would have to be an approved guild member. In America, runaway penalties did not extend beyond the borders of each colony, and, as Franklin’s narrative attests, the demand for skilled labor meant even a partially-trained apprentice would likely be hired, perhaps even with the status of a journeyman (though this label did not hold the weight it would in England). If an American apprentice ran away, his master would circulate a description of the runaway with an offer of reward, and if returned, the apprentice would have to serve for a longer period. The reward was the enforcement mechanism, meaning citizens might be on the lookout for apparent runaways.

Technically, to be legal, an apprenticeship contract (called an “indenture”) had to be registered with municipal authorities so it could be used as evidence in case of disputes. This was true even in the colonies. However, the nature of indenture papers meant that possession of one’s half of the contract should have constituted evidence without consulting town records: “indenture” papers were indented on both halves of the document so they could later be identified as one contract. Benjamin Franklin’s original contract with his brother would probably have been properly registered—but the second set of indentures, which were secret, would only have been held by the master and the apprentice. James probably could have proved that Benjamin was his apprentice by comparing the two halves of the indenture, but once his brother was out of Boston, this means of redress was impractical at best. And of course, in attempting to regain his apprentice, James would have had to admit his real ownership of the Courant. - [UVAstudstaff]wretched-stuffNeither of these poems has survived. But what Franklin was doing was a fairly typical thing in this period; newspapers were often filled with poems about recent events, particularly events as notable and spectacular as the two mentioned here. The death by drowning of George Worthilake, his wife and daughter (Franklin misremembers this as having been two daughters) as they were returning from church by boat to the lighthouse that Worthilake was in charge of in Novenber 1716 became known as the "Lighthouse Tragedy." Edward Teach, the pirate known as Blackbeard, was killed in a firefight with ships from the Royal Navy off the coast of North Carolina on November 22, 1718. The "Grub Street-ballad-style" that Franklin laments using here was nothing to be ashamed of; many authors in this period wrote popular ballads published in the kind of popular journals that became associated with "Grub Street," the physical home of mass market printing in London. - [UVAstudstaff]pointingpunctuation - [UVAstudstaff]SpectatorThe Spectator was a newspaper created by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele that ran from March 3, 1711 to December 6, 1712. It consisted of a series of essays that were for the most part written by either Steele or Addison, but they assumed the viewpoint of the persona of “Mr. Spectator.” “Mr. Spectator” was a quiet observer of English society who commented on politics, fashion, and social issues through these essays, which were widely popular in both England and the colonies. They were read as models of good English style, and also as guides for civilized, middle-class behavior. Benjamin Franklin was influenced by Spectator's prose style. And the persona of "Silence Dogood" that he would use in his own periodical essays was clearly influenced by the silent "Mr. Spectator" of Addison and Steele's influential journal. - [UVAstudstaff]third

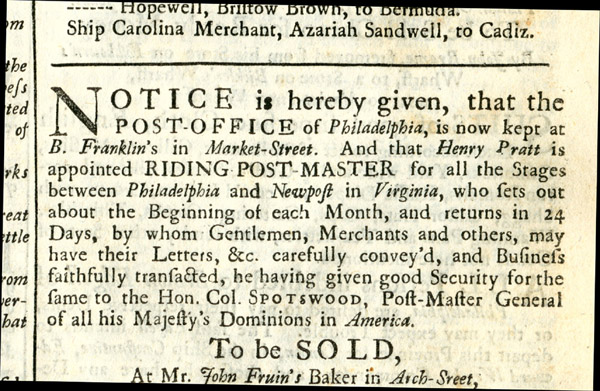

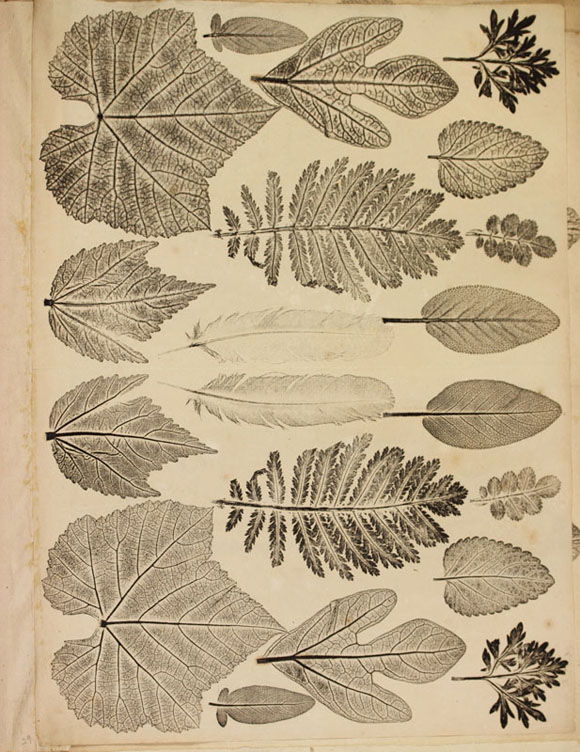

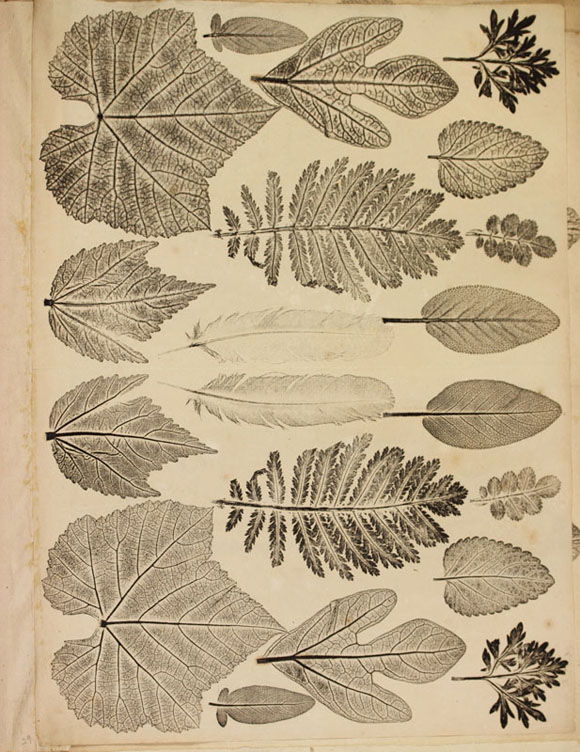

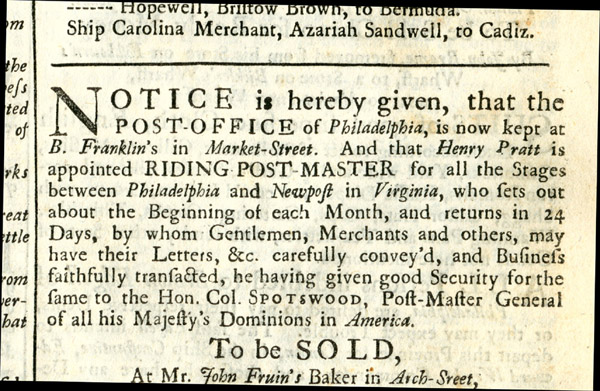

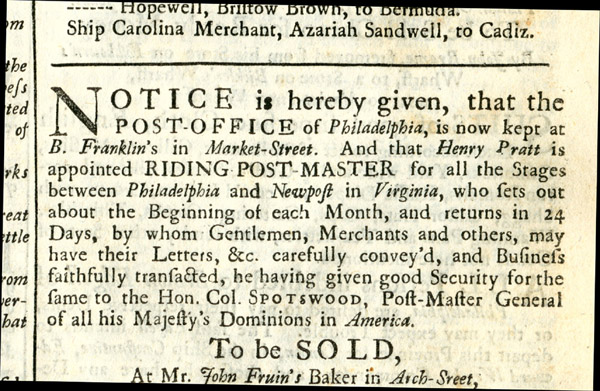

Given Franklin's later interest in public finance, it is striking to see that the particular essay of the Spectatorthat he remembers as his introduction to the series is a famous piece by Addison on the topic of "public credit." - [UVAstudstaff]vegetableThomas Tryon's The Way to Health, Long Life, and Happiness,  published in 1691, advocated a vegetarian diet. Which was unusual in this period; vegetarianism was rare, and it cannot have been easy to get enough nutrition through a vegetarian diet in colonial New England in this period, especially given the difficulty of finding fresh vegetables in the winter season. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) - [UVAstudstaff]hasty-puddingHasty pudding was a grain porridge; in the American colonies, it was usually made of corn, but could also be made of wheat, oats, or some other grain. - [UVAstudstaff]CockerEdward Cocker's textbook, first published in 1677 under the title Cocker's Arithmetick: being a plain and familiar method suitable to the meanest capacity for the full understanding of that incomparable art, as it is now taught by the ablest school-masters in city and country, and then republished under various titles for decades to come, became the standard book for learning basic arithmetic in the eighteenth-century Anglophone world. It would have been comparatively easy for Franklin to have come across a copy of this book, which went through scores of editions. - [UVAstudstaff]SellersPractical Navigation: or an Introduction to the Whole Art, first published in London in 1669, was a widely-reprinted text in the period; its author, John Seller (1632-1697) was a mapmaker and cartographer who was awarded with the title of "hydrophager to the king." Samuel Sturmy (1633-1669) was the author of The Mariner's Magazine, first published in 1669 and, like Seller's book, reprinted several times in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This was a large and ambitious text, with sections on navigation and math, but also on things like nautical weaponry. - [UVAstudstaff]LockeThe English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) published An Essay Concerning Human Understanding in 1690. Locke's philosophical skepticism and strong endorsement of religious toleration seem to have found a strong positive response in Franklin. Locke's book is still considered a foundational text in the philosophical tradition of English empiricism. - [UVAstudstaff]Port-RoyalLogic, or, The Art of Thinking written by Antoine Arnauld and Pierre Nicole, was published in French in 1662, and soon thereafter translated into English and other languages. Known familiarly as the "Port Royal Logic," this, like Locke's book, was a highly influential text for centuries, and is still read by historians of philosophy. Source: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/port-royal-logic/ - [UVAstudstaff]GreenwoodThe book that Franklin thinks that he is remembering is James Greenwood's An Essay towards a Practical English Grammar, first published in 1711. But he is probably misremembering here, since that book does not have the Socratic dialogue to which he refers. He is more likely thinking of A Grammar of the English Tongue, written by Charles Gildon in 1712, but published anonymously. That book concludes with an essay called "Of the Socratic Method in Disputing," that describes and then models a method of debating controversial topics by means of open-ended, non-confrontational questions. Franklin says that he took this kind of method to heart, training himself to handle disputes by avoiding dogmatic statements of his own position and instead asking careful questions so as better to learn the positions of others. - [UVAstudstaff]XenophonXenophon (430-354 B.C.E.) was an ancient Greek historian whose writings included the "Memorabilia," a text containing many Socratic-style dialogues. Source: http://www.iep.utm.edu/xenophon/ - [UVAstudstaff]Shaftesbury-and-CollinsFranklin is referring to works by Anthony Ashley Cooper, the earl of Shaftesbury, and Anthony Collins. Both authors were well known in this period for their philosophical skepticism and their classification as "deists." They believed that although a deity of some sort existed and had created the known universe, he, or perhaps better, it was not much concerned with the everyday doings of that creation. Franklin seems to have a read a lot of deist philosophy, which was widely influential in this period. - [UVAstudstaff]judiciouslyThese lines are from the 1711 poem "An Essay on Criticism" by Alexander Pope, though Franklin slightly misquotes, probably relying on his memory. - [UVAstudstaff]The-New-England-CourantFranklin is misremembering here, as there were other newspapers before these. But The New England Courant was indeed a landmark in newspaper publication in the American colonies, as it included poetry, opinion pieces, and other kinds of content beyond the official news.

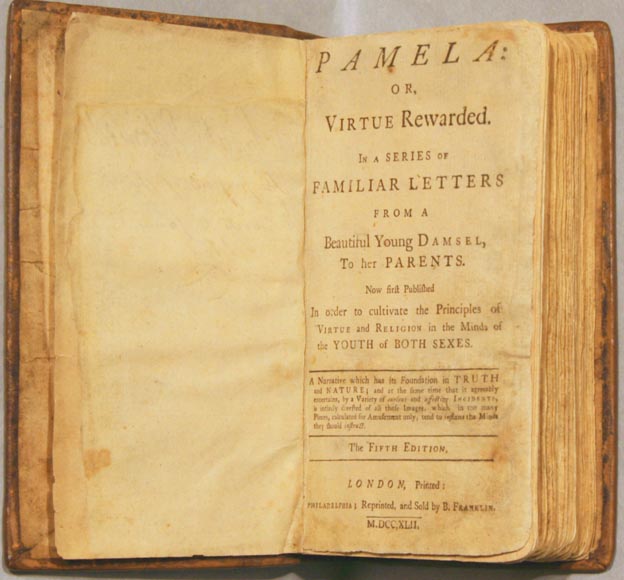

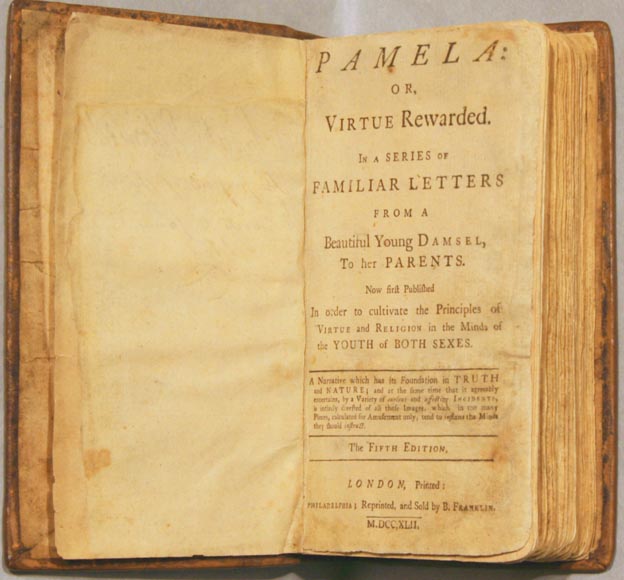

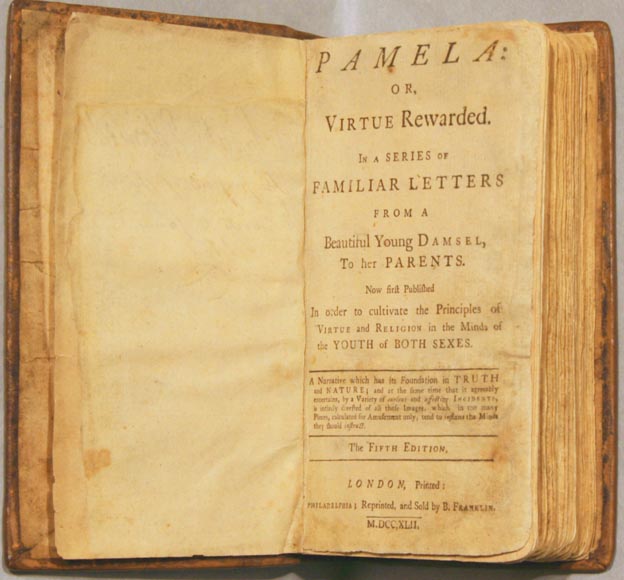

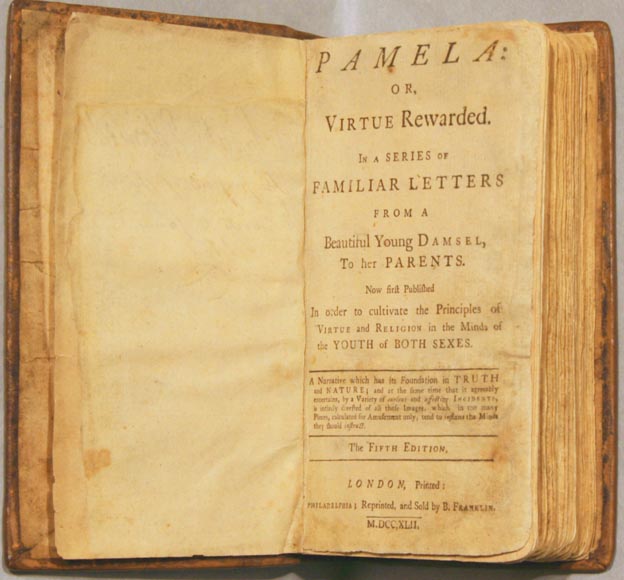

published in 1691, advocated a vegetarian diet. Which was unusual in this period; vegetarianism was rare, and it cannot have been easy to get enough nutrition through a vegetarian diet in colonial New England in this period, especially given the difficulty of finding fresh vegetables in the winter season. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons) - [UVAstudstaff]hasty-puddingHasty pudding was a grain porridge; in the American colonies, it was usually made of corn, but could also be made of wheat, oats, or some other grain. - [UVAstudstaff]CockerEdward Cocker's textbook, first published in 1677 under the title Cocker's Arithmetick: being a plain and familiar method suitable to the meanest capacity for the full understanding of that incomparable art, as it is now taught by the ablest school-masters in city and country, and then republished under various titles for decades to come, became the standard book for learning basic arithmetic in the eighteenth-century Anglophone world. It would have been comparatively easy for Franklin to have come across a copy of this book, which went through scores of editions. - [UVAstudstaff]SellersPractical Navigation: or an Introduction to the Whole Art, first published in London in 1669, was a widely-reprinted text in the period; its author, John Seller (1632-1697) was a mapmaker and cartographer who was awarded with the title of "hydrophager to the king." Samuel Sturmy (1633-1669) was the author of The Mariner's Magazine, first published in 1669 and, like Seller's book, reprinted several times in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This was a large and ambitious text, with sections on navigation and math, but also on things like nautical weaponry. - [UVAstudstaff]LockeThe English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) published An Essay Concerning Human Understanding in 1690. Locke's philosophical skepticism and strong endorsement of religious toleration seem to have found a strong positive response in Franklin. Locke's book is still considered a foundational text in the philosophical tradition of English empiricism. - [UVAstudstaff]Port-RoyalLogic, or, The Art of Thinking written by Antoine Arnauld and Pierre Nicole, was published in French in 1662, and soon thereafter translated into English and other languages. Known familiarly as the "Port Royal Logic," this, like Locke's book, was a highly influential text for centuries, and is still read by historians of philosophy. Source: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/port-royal-logic/ - [UVAstudstaff]GreenwoodThe book that Franklin thinks that he is remembering is James Greenwood's An Essay towards a Practical English Grammar, first published in 1711. But he is probably misremembering here, since that book does not have the Socratic dialogue to which he refers. He is more likely thinking of A Grammar of the English Tongue, written by Charles Gildon in 1712, but published anonymously. That book concludes with an essay called "Of the Socratic Method in Disputing," that describes and then models a method of debating controversial topics by means of open-ended, non-confrontational questions. Franklin says that he took this kind of method to heart, training himself to handle disputes by avoiding dogmatic statements of his own position and instead asking careful questions so as better to learn the positions of others. - [UVAstudstaff]XenophonXenophon (430-354 B.C.E.) was an ancient Greek historian whose writings included the "Memorabilia," a text containing many Socratic-style dialogues. Source: http://www.iep.utm.edu/xenophon/ - [UVAstudstaff]Shaftesbury-and-CollinsFranklin is referring to works by Anthony Ashley Cooper, the earl of Shaftesbury, and Anthony Collins. Both authors were well known in this period for their philosophical skepticism and their classification as "deists." They believed that although a deity of some sort existed and had created the known universe, he, or perhaps better, it was not much concerned with the everyday doings of that creation. Franklin seems to have a read a lot of deist philosophy, which was widely influential in this period. - [UVAstudstaff]judiciouslyThese lines are from the 1711 poem "An Essay on Criticism" by Alexander Pope, though Franklin slightly misquotes, probably relying on his memory. - [UVAstudstaff]The-New-England-CourantFranklin is misremembering here, as there were other newspapers before these. But The New England Courant was indeed a landmark in newspaper publication in the American colonies, as it included poetry, opinion pieces, and other kinds of content beyond the official news.  And it was the place where Benjamin Franklin's first surviving publications, his essays published in the Courant under the pseudonym "Silence Dogood" reached print. James Franklin ran afoul of the government several times in the course of publishing the newspaper (at one point, Benjamin took over as the official editor while his brother was in jail), and it was eventually suppressed, ceasing publication in June 1726. - [UVAstudstaff]anonymousFranklin is referring to the first of his essays published under the name "Silence Dogood." Writing in imitation of The Spectator, Franklin did something quite original in taking on the voice and persona of a woman, here an old widow who, in the course of the series, made observations on contemporary life. - [UVAstudstaff]BradfordWilliam Bradford (1663-1752), was one of the earliest printers in the American colonies. Born in England, he came to Pennsylvania in the 1680s and established the first printing office there. When he ran afoul of the political authorities in Pennsylvania in the 1690s, he moved to New York, and set up a print shop in the city, which he ran until the 1740s. He had government contracts for printing forms, paper money, and the proceedings of the New Jersey Assembly, and also issued the usual fare of printers in this period: religious tracts, almanacs, and eventually a newspaper, the New-York Gazette, the first newspaper published in the city. - [UVAstudstaff]AmboyPerth Amboy, New Jersey, at the southern end of the Arthur Kill (see below), and facing out on the Outer Harbor of New York City. - [UVAstudstaff]KillThe Arthur Kill, a body of water that runs between Staten Island and New Jersey, terminating at Perth Amboy. By "Long Island," Franklin is probably referring to the coastline of what is now Brooklyn, or perhaps the long peninsula now called the Rockaways. - [UVAstudstaff]shock-pateThe pate is the crown of your head, and a "shock" is a crop of hair, so the sense is that the Dutchman had a thick mass of hair to grab. - [UVAstudstaff]cutsCopper cut illustrations or engravings, which were expensive to produce. They would have been much more detailed and finer than the woodcuts used for cheap books. - [UVAstudstaff]CrusoDaniel Defoe (c.1660-1731), famous now as the author of Robinson Crusoe and other novels such as Moll Flanders, was at least as well known to readers in the period for his "conduct manuals"--guides to the proper way to live--such as The Family Instructor (1715)and Religious Courtship (1722), both of which went through multiple editions in the eighteenth century. - [UVAstudstaff]RichardsonSamuel Richardson's 1740 epistolary novel Pamela, or, Virtue Rewarded was one of the most popular novels of the period in the English-speaking world, and was also widely translated into other European languages. Franklin published an edition of the novel in 1742 in Philadelphia, which he labelled the "fifth edition" of the work without any authorization at all. (Image courtesy the American Antiquarian Society)

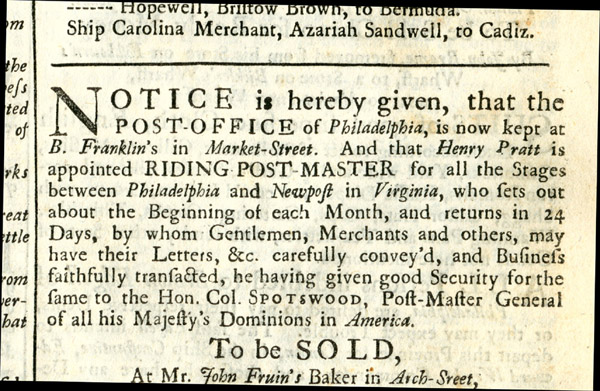

And it was the place where Benjamin Franklin's first surviving publications, his essays published in the Courant under the pseudonym "Silence Dogood" reached print. James Franklin ran afoul of the government several times in the course of publishing the newspaper (at one point, Benjamin took over as the official editor while his brother was in jail), and it was eventually suppressed, ceasing publication in June 1726. - [UVAstudstaff]anonymousFranklin is referring to the first of his essays published under the name "Silence Dogood." Writing in imitation of The Spectator, Franklin did something quite original in taking on the voice and persona of a woman, here an old widow who, in the course of the series, made observations on contemporary life. - [UVAstudstaff]BradfordWilliam Bradford (1663-1752), was one of the earliest printers in the American colonies. Born in England, he came to Pennsylvania in the 1680s and established the first printing office there. When he ran afoul of the political authorities in Pennsylvania in the 1690s, he moved to New York, and set up a print shop in the city, which he ran until the 1740s. He had government contracts for printing forms, paper money, and the proceedings of the New Jersey Assembly, and also issued the usual fare of printers in this period: religious tracts, almanacs, and eventually a newspaper, the New-York Gazette, the first newspaper published in the city. - [UVAstudstaff]AmboyPerth Amboy, New Jersey, at the southern end of the Arthur Kill (see below), and facing out on the Outer Harbor of New York City. - [UVAstudstaff]KillThe Arthur Kill, a body of water that runs between Staten Island and New Jersey, terminating at Perth Amboy. By "Long Island," Franklin is probably referring to the coastline of what is now Brooklyn, or perhaps the long peninsula now called the Rockaways. - [UVAstudstaff]shock-pateThe pate is the crown of your head, and a "shock" is a crop of hair, so the sense is that the Dutchman had a thick mass of hair to grab. - [UVAstudstaff]cutsCopper cut illustrations or engravings, which were expensive to produce. They would have been much more detailed and finer than the woodcuts used for cheap books. - [UVAstudstaff]CrusoDaniel Defoe (c.1660-1731), famous now as the author of Robinson Crusoe and other novels such as Moll Flanders, was at least as well known to readers in the period for his "conduct manuals"--guides to the proper way to live--such as The Family Instructor (1715)and Religious Courtship (1722), both of which went through multiple editions in the eighteenth century. - [UVAstudstaff]RichardsonSamuel Richardson's 1740 epistolary novel Pamela, or, Virtue Rewarded was one of the most popular novels of the period in the English-speaking world, and was also widely translated into other European languages. Franklin published an edition of the novel in 1742 in Philadelphia, which he labelled the "fifth edition" of the work without any authorization at all. (Image courtesy the American Antiquarian Society)  He was simply reprinting a copy of the book that had been obtained for him in London. The evidence suggests that it was not a great success commercially; novels remained suspect to many readers until well into the nineteenth century, and Franklin did not follow this up with other such piracies. - [UVAstudstaff]itinerantThat is, a traveling doctor. Nothing is known of Dr. John Browne's career as a physician except for what is recorded here. When Browne met Franklin, he was fifty-six years old and running an inn in Bordentown, New Jersey. - [UVAstudstaff]travestieA travesty is a parody, and doggerel verse would be deliberately bad, comically irregular verse designed to mock its subject. The English poet Charles Cotton (1630-1687) published "Scarronides, or, Virgil Travestie" in 1664 and 1665, a parody of Virgil's classical epic the Aeneid. Franklin is right; Browne's parodic version of the Bible does not appear ever to have been published. - [UVAstudstaff]KeimerBorn in England in 1689, Samuel Keimer ran a printing business in London in the 1710s, publishing a variety of things, including plays by Susanna Centlivre, essays by Daniel Defoe, and a newspaper. He also publishes several religious works, including some that testify to his affiliation with the "French Prophets," a millenarian group that preached in London in the early part of the eighteenth century (about which more below). Keimer was jailed in 1715 for seditious libel; the best guess is that he printed something in support of a failed Jacobite uprising in that year, but we cannot be sure. He moved to the American colonies sometime around 1720, and by 1723 he was once again printing, this time in Philadelphia. Much of what we know of Keimer's career in Philadelphia comes from Franklin, who, as we will see, was often dismissive of his abilities as a printer and his character. After going bankrupt in Philadelphia, Keimer ended up in Barbados, and founded the first newspaper there, the Barbados Gazette. He died in Barbados in 1742. Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. - [UVAstudstaff]ElegyThis broadside elegy for Aquila Rose, the young poet and printer whose death at the age of 28 was the reason why William Bradford had recommended Franklin to come to Philadelphia in the first place, is the first thing that Franklin printed in the city. The broadside was lost for decades, but a single copy was rediscovered just in the last few years, and is owned by the University of Pennsylvania Library:

He was simply reprinting a copy of the book that had been obtained for him in London. The evidence suggests that it was not a great success commercially; novels remained suspect to many readers until well into the nineteenth century, and Franklin did not follow this up with other such piracies. - [UVAstudstaff]itinerantThat is, a traveling doctor. Nothing is known of Dr. John Browne's career as a physician except for what is recorded here. When Browne met Franklin, he was fifty-six years old and running an inn in Bordentown, New Jersey. - [UVAstudstaff]travestieA travesty is a parody, and doggerel verse would be deliberately bad, comically irregular verse designed to mock its subject. The English poet Charles Cotton (1630-1687) published "Scarronides, or, Virgil Travestie" in 1664 and 1665, a parody of Virgil's classical epic the Aeneid. Franklin is right; Browne's parodic version of the Bible does not appear ever to have been published. - [UVAstudstaff]KeimerBorn in England in 1689, Samuel Keimer ran a printing business in London in the 1710s, publishing a variety of things, including plays by Susanna Centlivre, essays by Daniel Defoe, and a newspaper. He also publishes several religious works, including some that testify to his affiliation with the "French Prophets," a millenarian group that preached in London in the early part of the eighteenth century (about which more below). Keimer was jailed in 1715 for seditious libel; the best guess is that he printed something in support of a failed Jacobite uprising in that year, but we cannot be sure. He moved to the American colonies sometime around 1720, and by 1723 he was once again printing, this time in Philadelphia. Much of what we know of Keimer's career in Philadelphia comes from Franklin, who, as we will see, was often dismissive of his abilities as a printer and his character. After going bankrupt in Philadelphia, Keimer ended up in Barbados, and founded the first newspaper there, the Barbados Gazette. He died in Barbados in 1742. Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. - [UVAstudstaff]ElegyThis broadside elegy for Aquila Rose, the young poet and printer whose death at the age of 28 was the reason why William Bradford had recommended Franklin to come to Philadelphia in the first place, is the first thing that Franklin printed in the city. The broadside was lost for decades, but a single copy was rediscovered just in the last few years, and is owned by the University of Pennsylvania Library:  - [UVAstudstaff]compositorThat is, Keimer knew how to "compose"--to set type on a compositing stick and arrange lines on a form--but didn't know how to ink a page or otherwise use a printing press. Given that Keimer had been through London printing apprenticeship and had run print shops of his own, Keimer's apparent ignorance of these crucial tasks is surprising, and we only have Franklin's word to go on. It is possible that Keimer was a better printer than Franklin was willing to acknowledge, even if he did not have the kind of financial success that would come to Franklin later. - [UVAstudstaff]prophetsThe French Prophets, also known as the Camisards, were a millenarian sect who preached in London, and, then, other parts of England in the early part of the eighteenth century. They were begun by a small group of Huguenots, French Protestants who had fled persecution there by emigrating to England in 1706. They preached the imminent coming of the Messiah, and attracted a number of followers including, apparently for a while, Keimer. Like many people in this period, Franklin was suspicious of the kind of religious intensity displayed by Keimer and other millenarians, what Franklin calls "enthusiasm"; it shows up soon in his response, later, to the similarly intense preaching of George Whitfield, the evangelist and Methodist. - [UVAstudstaff]KeithSir William Keith (c. 1669–1749)

- [UVAstudstaff]compositorThat is, Keimer knew how to "compose"--to set type on a compositing stick and arrange lines on a form--but didn't know how to ink a page or otherwise use a printing press. Given that Keimer had been through London printing apprenticeship and had run print shops of his own, Keimer's apparent ignorance of these crucial tasks is surprising, and we only have Franklin's word to go on. It is possible that Keimer was a better printer than Franklin was willing to acknowledge, even if he did not have the kind of financial success that would come to Franklin later. - [UVAstudstaff]prophetsThe French Prophets, also known as the Camisards, were a millenarian sect who preached in London, and, then, other parts of England in the early part of the eighteenth century. They were begun by a small group of Huguenots, French Protestants who had fled persecution there by emigrating to England in 1706. They preached the imminent coming of the Messiah, and attracted a number of followers including, apparently for a while, Keimer. Like many people in this period, Franklin was suspicious of the kind of religious intensity displayed by Keimer and other millenarians, what Franklin calls "enthusiasm"; it shows up soon in his response, later, to the similarly intense preaching of George Whitfield, the evangelist and Methodist. - [UVAstudstaff]KeithSir William Keith (c. 1669–1749)  was granted the position of surveyor-general of the customs in the southern colonies of North America in 1713 by Robert Harley, then the leading minister in the government in Westminster. After his dismissal in July 1715 in a political purge, he persuaded William Penn, the proprietor of Pennsylvania, to appoint him to the position of deputy governor (this was in effect the leading executive power in the colony, since the monarch had the official title of governor). When Penn died in 1718, Keith tried to gain more power by creating a power base in the assembly. A political falling out took place when Keith sided with tradesmen and merchants on the issue of paper currency in 1723. Because of this, Keith's political opponents worked to oust him, and he was dismissed from the governorship in 1726. After this, Keith returned to England to appeal to the king for the governorship of the three lower colonies, but he was unsuccessful. He also attempted a few other political maneuvers, including an attempt at the governorship of New Jersey and the creation of a new colony called Georgia. He was unsuccessful at these as well. Penn found himself in financial trouble which led to a case against him, and he spent 1734 and 1735 in debtor's prison. After this, he became a journalist, and he died on November 18, 1749 in London. Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. - [UVAstudstaff]FrenchColonel John French was the speaker of the Delaware Assembly. "Madeira" is a fortified wine (that is, a wine with additional alcohol added to stabilize it) produced in the Madeira Islands, Portuguese-held islands off the west coast of Africa. Because this was the closest place to the American colonies where wine was made, Madeira wine was very popular there in the eighteenth century. But, expensive and taxed, Madeira wine was a luxury item, and would have been quite a treat for a seventeen-year-old, which is perhaps why Franklin remembers it so clearly. - [UVAstudstaff]shoalA sand bank or a place where the waters are shallow. Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]fortnightA fortnight consists of two weeks. Source: Oxford English Dictionary - [UVAstudstaff]raree-showA raree or "rarity" show would have been a small box carried by a traveling showman that had interesting images and scenes to be looked at, often through a small opening or peephole. They varied from perspective scenes of interesting places to, in some cases, pornography, and are the origins of the modern "peep show." - [UVAstudstaff]CollinsJohn Collins. Little is known of him beyond what Franklin says about in this memoir. - [UVAstudstaff]lampooningHarshly satirizing someone or something in writing. Source: Oxford English DictionarystrumpetsProstitues or unchaste women. Source: Oxford English DictionaryBurnetWilliam Burnet (1699-1729) was at this time the colonial governor of New York and New Jersey. His father Gilbert Burnet (1643-1715) was an important philosopher, cleric, and historian, whose multivolume History of the Reformation in England (1679-81) was a landmark history of the English church. Gilbert Burnet became an ally of both Charles II and William III, the latter of whom made him the Bishop of Salisbury. - [UVAstudstaff]drammingDrinking or alcohol consumption. Source: Oxford English DictionaryerrataAn error or mistake. Once again Franklin is using the language of printing to describe the course of his own life. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryone-hundred-pounds-sterlingDirectly converting 18th century currency into its modern equivalent is a problematic enterprise which relies on a variety of different methods (various sources gave numbers between $10,000 and $30,000 as a conversion for this hundred pounds). To better contextualize this number, a 1750s schoolmaster in America would earn around sixty pounds annually, while the British National Archives say that 100 pounds would buy you either 14 horses or 21 cows in the 1730s. These numbers are further complicated by the shortage of money in the colonies during the time, leading later in this piece to Franklin printing significant amounts of paper currency to fill the gap left by silver and gold.AnnisThomas Annis was the Captain of the London Hope, which sailed from Philadelphia to London once a year to carry the mail. It usually left in the fall; this year, the ship sailed in November. - [UVAstudstaff]becalmIn the case of a ship: motionless due to a lack of wind. Source: Oxford English DictionarytreppanTo lure, inveigle (into or to a place, course of action, etc., to do something, etc.). Source: Oxford English DictionaryMosaicThe ancient law of the Hebrews, contained in the Pentateuch. Source: Oxford English DictionarySeventhThat is, he takes Saturday as the Sabbath, like a member of the Jewish faith. Keimer may have started this (and growing out his beard, which was unusual in this era) when he considered himself to be a follower of the French Prophets. - [UVAstudstaff]flesh-potsIn the book of Exodus, Moses tells the Israelites not to eat meat while in the desert, leading them to wish that they could return to the pots of meat they had left behind in Egypt. - [UVAstudstaff]CharlesAs with a number of people in Franklin's early life, pretty much the only things we know about Charles Osborne and Joseph Watson come via Franklin. Charles Osborne eventually became a lawyer and moved to the Caribbean, where he died. Joseph Watson died just a few years after the events described here, in April 1727, in Franklin's arms. We know the most about James Ralph, because he became a prolific author once he moved to London. Ralph (d. 1762) was probably born between 1695 and 1710, perhaps in the environs of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, or perhaps in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. He never returned to America after the journey Franklin describes here. In 1727, he began to publish poetry, notably The Tempest, or, The Terrors of Death (1727) and Night (1728). In 1728 his blank verse polemic, Sawney, an Heroic Poem Occasion’d by the Dunciad was published, resulting in his inclusion in Alexander Pope’s second edition of the Dunciad (which may have been his intention). Ralph became a friend of Henry Fielding when Fielding was a leading figure in the London theater, and tried his hand as a playwright. But Ralph had his greatest financial success when he became a political journalist. Beginning in the 1730s, he was a contributor to a number of London newspapers. His most important works are The History of England during the reigns of King William, Queen Anne, and King George I, with an introductory review of the reigns of the royal brothers Charles and James (1744–6) and The Case of the Authors by Profession or Trade Stated (1758). Source: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography - [UVAstudstaff]SchuylkillThe Schuylkill River runs through eastern Pennsylvania, meeting the Delaware River at Philadelphia.