The Silence Dogood Essays

By

Benjamin Franklin

Silence_DogoodBenjamin Franklin was sixteen years old and working as an apprentice in the Boston print shop of his older brother James when, in April 1722, he began writing a series of essays to be published in the New-England Courant (which his brother published) under the pseudonym of "Silence Dogood." In his Autobiography, Benjamin remembered slipping these essays, written in disguised handwriting, under the door of the Courant's office; he assumed (probably correctly) that James would refuse to print an essay from him if he simply asked or submitted it under his own name. James published the essays, which became very popular among the newspaper's readers. Benjamin kept his authorship of the series a secret, even from his brother, until after he finished writing them in October 1722, at which point James printed an advertisement asking for "Silence Dogood" to come forth. Benjamin confessed that he was the author, which seems to have annoyed his older brother. It was not too long after that that Benjamin left his brother's shop--breaking his apprenticeship--and moved to Philadelphia.

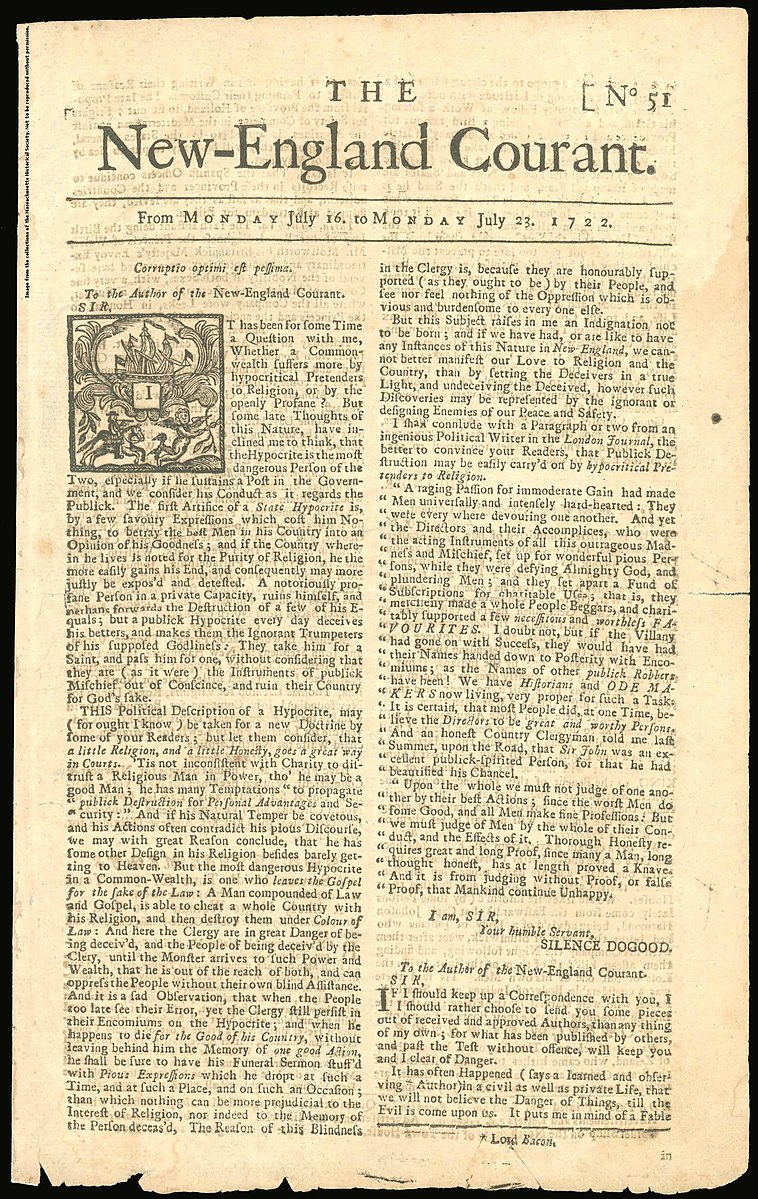

Source: An issue of the New England Courant with one of the Silence Dogood issues on the front page. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Silence Dogood essays are written in the persona of a middle-aged woman, but

the title character is very clearly indebted to Mr. Spectator, the avatar of

Addison and Steele's Spectator series, published a decade

earlier. It is testimony to how widely influential the Spectator was that even in colonial America, teenaged boys were

reading it and taking it as a model for their own writing. In the Autobiography, Franklin remembers how much he loved the

Spectator, and how he first came across it at the age

of sixteen: "an odd volume of the Spectator fell into my

hands. This was a publication I had never seen. I bought the volume, and

read it again and again. I was enchanted with it, thought the style

excellent, and wished it were in my power to imitate it. With this view I

selected some of the papers, made short summaries of the sense of each

period, and put them for a few days aside. I then, without looking at the

book, endeavoured to restore the essays to their true form, and to express

each thought at length, as it was in the original, employing the most

appropriate words that occurred to my mind. I afterwards compared my

Spectator with the original; I perceived some faults, which I

corrected." If the Spectator gave Franklin a model

for his prose style, so too did it give him a persona to inhabit; the "Silence"

in Silence Dogood's name clearly alludes to the taciturn Mr. Spectator as

invented by Addison and Steele. The surname "Dogood" also alludes to a famous

writer, in this case a colonial writer: the prolific Boston cleric Cotton

Mather, whose 1710 collection Bonifacius: or, Essays to Do

Good, advocating the reader to undertake charitable works, Franklin

also remembered as a book that had a great impact on him as a young man. The

startling thing about the Silence Dogood essays (in addition to the fact that

they were written by a sixteen-year-old), is that Franklin adopts the persona of

a woman, a persona that enables him adopt, but also gently mock, the kinds of

sentiments expressed by authority figures like Mather. Franklin would continue

to use personae, male and female, throughout his career, the most famous of

these being the Poor Richard of his Almanack. And there's a sense in which the

"Benjamin Franklin" of the Autobiography and of history

was also a persona, a role that Franklin played on the public stage of the

trans-Atlantic world.

Source: An issue of the New England Courant with one of the Silence Dogood issues on the front page. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Silence Dogood essays are written in the persona of a middle-aged woman, but

the title character is very clearly indebted to Mr. Spectator, the avatar of

Addison and Steele's Spectator series, published a decade

earlier. It is testimony to how widely influential the Spectator was that even in colonial America, teenaged boys were

reading it and taking it as a model for their own writing. In the Autobiography, Franklin remembers how much he loved the

Spectator, and how he first came across it at the age

of sixteen: "an odd volume of the Spectator fell into my

hands. This was a publication I had never seen. I bought the volume, and

read it again and again. I was enchanted with it, thought the style

excellent, and wished it were in my power to imitate it. With this view I

selected some of the papers, made short summaries of the sense of each

period, and put them for a few days aside. I then, without looking at the

book, endeavoured to restore the essays to their true form, and to express

each thought at length, as it was in the original, employing the most

appropriate words that occurred to my mind. I afterwards compared my

Spectator with the original; I perceived some faults, which I

corrected." If the Spectator gave Franklin a model

for his prose style, so too did it give him a persona to inhabit; the "Silence"

in Silence Dogood's name clearly alludes to the taciturn Mr. Spectator as

invented by Addison and Steele. The surname "Dogood" also alludes to a famous

writer, in this case a colonial writer: the prolific Boston cleric Cotton

Mather, whose 1710 collection Bonifacius: or, Essays to Do

Good, advocating the reader to undertake charitable works, Franklin

also remembered as a book that had a great impact on him as a young man. The

startling thing about the Silence Dogood essays (in addition to the fact that

they were written by a sixteen-year-old), is that Franklin adopts the persona of

a woman, a persona that enables him adopt, but also gently mock, the kinds of

sentiments expressed by authority figures like Mather. Franklin would continue

to use personae, male and female, throughout his career, the most famous of

these being the Poor Richard of his Almanack. And there's a sense in which the

"Benjamin Franklin" of the Autobiography and of history

was also a persona, a role that Franklin played on the public stage of the

trans-Atlantic world.There were fourteen Silence Dogood essays in all, published every two weeks in the pages of the New England Courant, for which, as we have seen, James Franklin was the publisher. The New England Courant was the first independently-published newspaper in colonial America; that is, it operated independently of government authority. So much so that the colonial government in Massachusetts frequently attempted to censor the newspaper and jailed James Franklin several times when he published articles that were thought to defame public officials (Cotton Mather, for example). During these periods, Benjamin was listed as the official publisher of the newspaper. It was finally closed for good in 1726. Benjamin had long since moved on, and was at this point finishing a stint as a journeyman printer in London and preparing to return to Philadelphia, where he opened a print shop of his own. April 2, 1722 [No. 1] To the Author of the New-England Courant.

Sir,

It may not be improper in the first place to inform your Readers, that I intend once a Fortnightfortnight to present them, by the Help of this Paper, with a short Epistleepistle, which I presume will add somewhat to their Entertainment.

And since it is observed, that the Generality of People, now a days, are unwilling either to commend or dispraisedispraise what they read, until they are in some measure informed who or what the Author of it is, whether he be poor or rich, old or young, a Schollar or a Leather Apron Manleatherapron, &cetc and give their Opinion of the Performance, according to the Knowledge which they have of the Author's Circumstances, it may not be amiss to begin with a short Account of my past Life and present Condition, that the Reader may not be at a Loss to judge whether or nowhether my Lucubrationslucubrations are worth his reading.

At the time of my Birth, my Parents were on Ship-board in their Way from London to N. Englandnengland. My Entrance into this troublesome World was attended with the Death of my Father, a Misfortune, which tho' I was not then capable of knowing, I shall never be able to forget; for as he, poor Man, stood upon the Deck rejoycing at my Birth, a merciless Wave entred the Ship, and in one Moment carry'd him beyond Reprieve. Thus, was the first Day which I saw, the last that was seen by my Father; and thus was my disconsolatedisconsolate Mother at once made both a Parent and a Widow.

When we arrived at Boston (which was not long after) I was put to Nurse in a Country Place, at a small Distance from the Town, where I went to School, and past my Infancy and Childhood in Vanity and Idleness, until I was bound out Apprenticeapprentice, that I might no longer be a Charge to my Indigentindigent Mother, who was put to hard Shifts for a Living.

My Master was a Country Minister, a pious good-natur'd young Man, and a Batchelor: he labour'd with all his Might to instil vertuous and godly Principles into my tender Soul, well knowing that it was the most suitable Time to make deep and lasting Impressions on the Mind, while it was yet untainted with Vice, free and unbiass'd. He endeavour'd that I might be instructed in all that Knowledge and Learning which is necessary for our Sex, and deny'd me no Accomplishment that could possibly be attained in a Country Place; such as all Sorts of Needle-Work, Writing, Arithmetick, &c. and observing that I took a more than ordinary Delight in reading ingenious Booksliteracy, he gave me the free Use of his Library, which tho' it was but small, yet it was well chose, to inform the Understanding rightly, and enable the Mind to frame great and noble Ideas.

Before I had liv'd quite two Years with this Reverend Gentleman, my indulgent Mother departed this Life, leaving me as it were by my self, having no Relation on Earth within my Knowledge.

I will not abuse your Patience with a tedious Recital of all the frivolous Accidents of my Life, that happened from this Time until I arrived to Years of Discretiondiscretion, only inform you that I liv'd a chearful Country Life, spending my leisure Time either in some innocent Diversion with the neighbouring Females, or in some shady Retirement, with the best of Company, Books. Thus I past away the Time with a Mixture of Profit and Pleasure, having no affliction but what was imaginary, and created in my own Fancy; as nothing is more common with us Women, than to be grieving for nothing, when we have nothing else to grieve for.

As I would not engross too much of your Paper at once, I will defer the Remainder of my Story until my next Letter; in the mean time desiring your Readers to exercise their Patience, and bear with my Humours now and then, because I shall trouble them but seldom. I am not insensible of the Impossibility of pleasing all, but I would not willingly displease any; and for those who will take Offence werewere none is intended, they are beneath the Notice of Your Humble Servant,

SILENCE DOGOOD.

April 16, 1722 [No. 2] To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

Histories of Lives are seldom entertaining, unless they contain something either admirable or exemplar: And since there is little or nothing of this Nature in my own Adventures, I will not tire your Readers with tedious Particulars of no Consequence, but will briefly, and in as few Words as possible, relate the most material Occurrences of my Life, and according to my Promise, confine all to this Letter.

My Reverend master who had hitherto remained a Batchelor, (after much meditation on the Eighteenth verse of the Second Chapter of Genesisgenesis,) took up a Resolution to marry; and having made several unsuccessful fruitless Attempts on the more topping Sort of our Sextopsex, and being tir'd with making troublesome Journeys and Visits to no Purpose, he began unexpectedly to cast a loving Eye upon Me, whom he had brought up cleverly to his Hand.

There is certainly scarce any Part of a Man's Life in which he appears more silly and ridiculous, than when he makes his first Onset in Courtship. The aukward Manner in which my Master first discover'd his Intentions, made me, in spite of my Reverence to his Person, burst out into an unmannerly Laughter: However, having ask'd his Pardon, and with much ado compos'd my Countenance, I promis'd him I would take his Proposal into serious Consideration, and speedily give him an Answer.

As he had been a great Benefactor (and in a Manner a Father to me) I could not well deny his Request, when I once perceived he was in earnest. Whether it was Love, or Gratitude, or Pride, or all Three that made me consent, I know not; but it is certain, he found it no hard Matter, by the Help of his Rhetorick, to conquer my Heart, and perswade me to marry him.

This unexpected Match was very astonishing to all the Country round about, and served to furnish them with Discourse for a long Time after; some approving it, others disliking it, as they were led by their various Fancies and Inclinations.

We lived happily together in the Heighth of conjugal Love and mutual Endearments, for near Seven Years, in which Time we added Two likely Girls and a Boy to the Family of the Dogoods: But alas! When my Sun was in its meridian Altitudemeridian, inexorable unrelenting Death, as if he had envy'd my Happiness and Tranquility, and resolv'd to make me entirely miserable by the Loss of so good an Husband, hastened his Flight to the Heavenly World, by a sudden unexpected Departure from thisthisworld.

I have now remained in a State of Widowhood for several Years, but it is a State I never much admir'd, and I am apt to fancy that I could be easily perswaded to marry again, provided I was sure of a good-humour'd, sober, agreeable Companion: But one, even with these few good Qualities, being hard to find, I have lately relinquish'd all Thoughts of that Nature.

At present I pass away my leisure Hours in Conversation, either with my honest Neighbour Rusticus and his Family, or with the ingenious Minister of our Town, who now lodges at my House, and by whose Assistance I intend now and then to beautify my Writings with a Sentence or two in the learned Languages, which will not only be fashionable, and pleasing to those who do not understand it, but will likewise be very ornamental.

I shall conclude this with my own Character, which (one would think) I should be best able to give. Know then, That I am an Enemy to Vice, and a Friend to Vertue. I am one of an extensive Charity, and a great Forgiver of private Injuries: A hearty Lover of the Clergy and all good Men, and a mortal Enemy to arbitrary Government and unlimited Power. I am naturally very jealous for the Rights and Liberties of my Country; and the least appearance of an Incroachment on those invaluable Priviledges, is apt to make my Blood boil exceedingly. I have likewise a natural Inclination to observe and reprove the Faults of others, at which I have an excellent Faculty. I speak this by Way of Warning to all such whose Offences shall come under my Cognizance, for I never intend to wrap my Talent in a Napkin. To be brief; I am courteous and affable, good humour'd (unless I am first provok'd,) and handsome, and sometimes witty, but always, Sir, Your Friend and Humble Servant,

SILENCE DOGOOD.

April 30, 1722 [No. 3] To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir.

It is undoubtedly the Duty of all Persons to serve the Country they live in, according to their Abilities; yet I sincerely acknowledge, that I have hitherto been very deficient in this Particular; whether it was for want of Will or Opportunity, I will not at present stand to determine: Let it suffice, that I now take up a Resolution, to do for the future all that lies in my Way for the Service of my Countrymen.

I have from my Youth been indefatigablyindefatigably studious to gain and treasure up in my Mind all useful and desireable Knowledge, especially such as tends to improve the Mind, and enlarge the Understanding: And as I have found it very beneficial to me, I am not without Hopes, that communicating my small Stock in this Manner, by Peace-mealpeacemeal to the Publick, may be at least in some Measure useful.

I am very sensible that it is impossible for me, or indeed any one Writer to please all Readers at once. Various Persons have different Sentiments; and that which is pleasant and delightful to one, gives another a Disgust. He that would (in this Way of Writing) please all, is under a Necessity to make his Themes almost as numerous as his Letters. He must one while be merry and diverting, then more solid and serious; one while sharp and satyrical, then (to mollifymollify that) be sober and religious; at one Time let the Subject be Politicks, then let the next Theme be Love: Thus will every one, one Time or other find some thing agreeable to his own Fancy, and in his Turn be delighted.

According to this Method I intend to proceed, bestowing now and then a few gentle Reproofsreproof on those who deserve them, not forgetting at the same time to applaud those whose Actions merit Commendation. And here I must not forget to invite the ingenious Part of your Readers, particularly those of my own Sex to enter into a Correspondence with me, assuring them, that their Condescension in this Particular shall be received as a Favour, and accordingly acknowledged.

I think I have now finish'd the Foundation, and I intend in my next to begin to raise the Building. Having nothing more to write at present, I must make the usual excuse in such Cases, of being in haste, assuring you that I speak from my Heart when I call my self, The most humble and obedient of all the Servants your Merits have acquir'd,

SILENCE DOGOOD.

May 14, 1722 [No. 4] An sum etiam nunc vel Graecè loqui vel Latinè docendus? Cicero.cicerotrans To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

Discoursing the other Day at Dinner with my Reverend Boarder, formerly mention'd, (whom for Distinction sake we will call by the Name of Clericus,) concerning the Education of Children, I ask'd his Advice about my young Son William, whether or no I had best bestow upon him Academical Learning, or (as our Phrase is) bring him up at our College: He perswaded me to do it by all Means, using many weighty Arguments with me, and answering all the Objections that I could form against it; telling me withal, that he did not doubt but that the Lad would take his Learning very well, and not idle away his Time as too many there now-a-days do. These Words of Clericus gave me a Curiosity to inquire a little more strictly into the present Circumstances of that famous Seminaryseminary of Learning; but the Information which he gave me, was neither pleasant, nor such as I expected.

As soon as Dinner was over, I took a solitary Walk into my Orchard, still ruminating on Clericus's Discourse with much Consideration, until I came to my usual Place of Retirement under the Great Apple-Tree; where having seated my self, and carelessly laid my Head on a verdantverdant Bank, I fell by Degrees into a soft and undisturbed Slumber. My waking Thoughts remained with me in my Sleep, and before I awak'd again, I dreamt the following Dream.

I fancy'd I was travelling over pleasant and delightful Fields and Meadows, and thro' many small Country Towns and Villages; and as I pass'd along, all Places resounded with the Fame of the Temple of Learning: Every Peasant, who had wherewithal, was preparing to send one of his Children at least to this famous Place; and in this Case most of them consulted their own Purses instead of their Childrens Capacities: So that I observed, a great many, yea, the most part of those who were travelling thither, were little better than Dunces and Blockheads. Alas! alas!

At length I entred upon a spacious Plain, in the Midst of which was erected a large and stately Edifice: It was to this that a great Company of Youths from all Parts of the Country were going; so stepping in among the Crowd, I passed on with them, and presently arrived at the Gate.

The Passage was kept by two sturdy Portersporter named Riches and Poverty, and the latter obstinately refused to give Entrance to any who had not first gain'd the Favour of the former; so that I observed, many who came even to the very Gate, were obliged to travel back again as ignorant as they came, for want of this necessary Qualification. However, as a Spectatorspectator I gain'd Admittance, and with the rest entred directly into the Temple.

In the Middle of the great Hall stood a stately and magnificent Throne, which was ascended to by two high and difficult Steps. On the Top of it sat Learning in awful State; she was apparelled wholly in Black, and surrounded almost on every Side with innumerable Volumes in all Languages. She seem'd very busily employ'd in writing something on half a Sheet of Paper, and upon Enquiry, I understood she was preparing a Paper, call'd, The New-England Courant. On her Right Hand sat English, with a pleasant smiling Countenance, and handsomely attir'd; and on her left were seated several Antique Figures with their Faces vail'd. I was considerably puzzl'd to guess who they were, until one informed me, (who stood beside me,) that those Figures on her left Hand were Latin, Greek, Hebrew, &c. and that they were very much reserv'd, and seldom or never unvail'd their Faces here, and then to few or none, tho' most of those who have in this Place acquir'd so much Learning as to distinguish them from English, pretended to an intimate Acquaintance with them. I then enquir'd of him, what could be the Reason why they continued vail'd, in this Place especially: He pointed to the Foot of the Throne, where I saw Idleness, attended with Ignorance, and these (he informed me) were they, who first vail'd them, and still kept them so.

Now I observed, that the whole Tribe who entred into the Temple with me, began to climb the Throne; but the Work proving troublesome and difficult to most of them, they withdrew their Hands from the Plow, and contented themselves to sit at the Foot, with Madam Idleness and her Maid Ignorance, until those who were assisted by Diligence and a docibledocible Temper, had well nighnigh got up the first Step: But the Time drawing nigh in which they could no way avoid ascending, they were fainfain to crave the Assistance of those who had got up before them, and who, for the Reward perhaps of a Pint of Milk, or a Piece of Plumb-Cakecake, lent the Lubberslubber a helping Hand, and sat them in the Eye of the World, upon a Level with themselves.

The other Step being in the same Manner ascended, and the usual Ceremonies at an End, every Beetle-Scull seem'd well satisfy'd with his own Portion of Learning, tho' perhaps he was e'en just as ignorant as ever. And now the Time of their Departure being come, they march'd out of Doors to make Room for another Company, who waited for Entrance: And I, having seen all that was to be seen, quitted the hall likewise, and went to make my Observations on those who were just gone out before me.

Some I perceiv'd took to Merchandizingmerch, others to Travelling, some to one Thing, some to another, and some to Nothing; and many of them from henceforth, for want of Patrimonypatrimony, liv'd as poor as Church Micechurchmice, being unable to dig, and asham'd to beg, and to live by their Wits it was impossible. But the most Part of the Crowd went along a large beaten Path, which led to a Temple at the further End of the Plain, call'd, The Temple of Theologytheology. The Business of those who were employ'd in this Temple being laborious and painful, I wonder'd exceedingly to see so many go towards it; but while I was pondering this Matter in my Mind, I spy'd Pecuniapecunia behind a Curtain, beckoning to them with her Hand, which Sight immediately satisfy'd me for whose Sake it was, that a great Part of them (I will not say all) travel'd that Road. In this Temple I saw nothing worth mentioning, except the ambitious and fraudulent Contrivances of Plagiusplagius, who (notwithstanding he had been severely reprehended for such Practices before) was diligently transcribing some eloquent Paragraphs out of Tillotson's Workstillotson, &c., to embellish his own.

Now I bethought my self in my Sleep, that it was Time to be at Home, and as I fancy'd I was travelling back thither, I reflected in my Mind on the extream Folly of those Parents, who, blind to their Childrens Dulness, and insensible of the Solidity of their Skulls, because they think their Purses can afford it, will needs send them to the Temple of Learning, where, for want of a suitable Genius, they learn little more than how to carry themselves handsomely, and enter a Room genteelygenteel, (which might as well be acquir'd at a Dancing-School,) and from whence they return, after Abundance of Trouble and Charge, as great Blockheads as ever, only more proud and self-conceited.

While I was in the midst of these unpleasant Reflections, Clericus (who with a Book in his Hand was walking under the Trees) accidentally awak'd me; to him I related my Dream with all its Particulars, and he, without much Study, presently interpreted it, assuring me, That it was a lively Representation of Harvard College, Etcetera. I remain, Sir, Your Humble Servant,

SILENCE DOGOOD.

May 28, 1722 [No. 5] Mulier Mulieri magis congruet. Ter.terencetrans To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

I shall here present your Readers with a Letter from one, who informs me that I have begun at the wrong End of my Business, and that I ought to begin at Home, and censure the Vices and Follies of my own Sex, before I venture to meddle with your's: Nevertheless, I am resolved to dedicate this Speculation to the Fair Tribe, and endeavour to show, that Mr. Ephraim charges Women with being particularly guilty of Pride, Idleness, &c. wrongfully, inasmuch as the Men have not only as great a Share in those Vices as the Women, but are likewise in a great Measure the Cause of that which the Women are guilty of. I think it will be best to produce my Antagonist, before I encounter him.

"Madam

"My Design in troubling you with this Letter is, to desire you would begin with your own Sex first: Let the first Volley of your Resentments be directed against Female Vice; let Female Idleness, Ignorance and Folly, (which are Vices more peculiar to your Sex than to our's,) be the Subject of your Satyrssatyr, but more especially Female Pride, which I think is intollerable. Here is a large Field that wants Cultivation, and which I believe you are able (if willing) to improve with Advantage; and when you have once reformed the Women, you will find it a much easier Task to reform the Men, because Women are the prime Causes of a great many Male Enormitiesmaleenormity. This is all at present from Your Friendly Wellwisher,

Ephraim Censoriousephraim

After Thanks to my Correspondent for his Kindness in cutting out Work for me, I must assure him, that I find it a very difficult Matter to reprovereprove Women separate from the Men; for what Vice is there in which the Men have not as great a Share as the Women? and in some have they not a far greater, as in Drunkenness, Swearing, &c.? And if they have, then it follows, that when a Vice is to be reproved, Men, who are most culpable, deserve the most Reprehension, and certainly therefore, ought to have it. But we will wave this Point at present, and proceed to a particular Consideration of what my Correspondent calls Female Vice.

As for Idleness, if I should Quaerequaere, Where are the greatest Number of its Votariesvotary to be found, with us or the Men? it might I believe be easily and truly answer'd, With the latter. For notwithstanding the Men are commonly complaining how hard they are forc'd to labour, only to maintain their Wives in Pomppomp and Idleness, yet if you go among the Women, you will learn, that they have always more Work upon their Hands than they are able to do; and that a Woman's Work is never done, &c. But however, Suppose we should grant for once, that we are generally more idle than the Men, (without making any Allowance for the Weakness of the Sex,) I desire to know whose Fault it is? Are not the Men to blame for their Folly in maintaining us in Idleness? Who is there that can be handsomely Supported in Affluence, Ease and Pleasure by another, that will chuse rather to earn his Bread by the Sweat of his own Brows? And if a Man will be so fond and so foolish, as to labour hard himself for a Livelihood, and suffer his Wife in the mean Time to sit in Ease and Idleness, let him not blame her if she does so, for it is in a great Measure his own Fault.

And now for the Ignorance and Folly which he reproachesreproach us with, let us see (if we are Fools and Ignoramus's) whose is the Fault, the Men's or our's. An ingenious Writer, having this Subject in Hand, has the following Words, wherein he lays the Fault wholly on the Men, for not allowing Women the Advantages of Education.

"I have (says he) often thought of it as one of the most barbarous Customs in the World, considering us as a civiliz'd and Christian Country, that we deny the Advantages of Learning to Women. We reproach the Sex every Day with Folly and Impertinence, while I am confident, had they the Advantages of Education equal to us, they would be guilty of less than our selves. One would wonder indeed how it should happen that Women are conversibleconversible at all, since they are only beholding to natural Parts for all their Knowledge. Their Youth is spent to teach them to stitch and sew, or make Baublesbaubles: They are taught to read indeed, and perhaps to write their Names, or so; and that is the Heighth of a Womans Education. And I would but ask any who slight the Sex for their Understanding, What is a Man (a Gentleman, I mean) good for that is taught no more? If Knowledge and Understanding had been useless Additions to the Sex, God Almighty would never have given them Capacities, for he made nothing Needless. What has the Woman done to forfeit the Priviledge of being taught? Does she plague us with her Pride and Impertinenceimpertinence? Why did we not let her learn, that she might have had more Wit? Shall we upbraidupbraid Women with Folly, when 'tis only the Error of this inhumane Custom that hindred them being made wiser."

So much for Female Ignorance and Folly, and now let us a little consider the Pride which my Correspondent thinks is intollerable. By this Expression of his, one would think he is some dejected Swainswain, tyranniz'd over by some cruel haughty Nymphnymph, who (perhaps he thinks) has no more Reason to be proud than himself. Alas-a-day! What shall we say in this Case! Why truly, if Women are proud, it is certainly owing to the Men still; for if they will be such Simpletons as to humble themselves at their Feet, and fill their credulouscredulous Ears with extravagant Praises of their Wit, Beauty, and other Accomplishments (perhaps where there are none too,) and when Women are by this Means perswaded that they are Something more than humane, what Wonder is it, if they carry themselves haughtily, and live extravagantly. Notwithstanding, I believe there are more Instances of extravagant Pride to be found among Men than among Women, and this Fault is certainly more hainous in the former than in the latter.

Upon the whole, I conclude, that it will be impossible to lash any Vice, of which the Men are not equally guilty with the Women, and consequently deserve an equal (if not a greater) Share in the Censure. However, I exhortexhort both to amend, where both are culpableculpable, otherwise they may expect to be severely handled by Sir, Your Humble Servant,

SILENCE DOGOOD

N.B. Mrs. Dogood has lately left her Seat in the Country, and come to Boston, where she intends to tarrytarry for the Summer Season, in order to compleat her Observations of the present reigning Vices of the Town.

June 11, 1722 [No. 6] Quem Dies videt veniens Superbum, Hunc Dies vidit fugiens jacentem. Seneca.senecatrans To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

Among the many reigning Vices of the Town which may at any Time come under my Consideration and Reprehension, there is none which I am more inclin'd to expose than that of Pride. It is acknowledg'd by all to be a Vice the most hateful to God and Man. Even those who nourish it in themselves, hate to see it in others. The proud Man aspires after Nothing less than an unlimited Superiority over his Fellow-Creatures. He has made himself a King in SoliloquySsoliloquy; fancies himself conquering the World; and the Inhabitants thereof consulting on proper Methods to acknowledge his Merit. I speak it to my Shame, I my self was a Queen from the Fourteenth to the Eighteenth Year of my Age, and govern'd the World all the Time of my being govern'd by my Master. But this speculative Pride may be the Subject of another Letter: I shall at present confine my Thoughts to what we call Pride of Apparel. This Sort of Pride has been growing upon us ever since we parted with our Homespun Cloaths for Fourteen Penny Stuffspenny, &c. And the Pride of Apparel has begotbegot and nourish'd in us a Pride of Heart, which portendsportend the Ruin of Church and State. Pride goeth before Destruction, and a haughty Spirit before a Fall: And I remember my late Reverend Husband would often say upon this Text, That a Fall was the natural Consequence, as well as Punishment of Pride. Daily Experience is sufficient to evinceevince the Truth of this Observation. Persons of small Fortune under the Dominion of this Vice, seldom consider their Inability to maintain themselves in it, but strive to imitate their Superiors in Estate, or Equals in Folly, until one Misfortune comes upon the Neck of another, and every Step they take is a Step backwards. By striving to appear rich they become really poor, and deprive themselves of that Pity and Charity which is due to the humble poor Man, who is made so more immediately by Providence.

This Pride of Apparel will appear the more foolish, if we consider, that those airy Mortals, who have no other Way of making themselves considerable but by gorgeous Apparel, draw after them Crowds of Imitators, who hate each other while they endeavour after a Similitude of Manners. They destroy by Example, and envy one another's Destruction.

I cannot dismiss this Subject without some Observations on a particular Fashion now reigning among my own Sex, the most immodest and inconvenient of any the Art of Woman has invented, namely, that of Hoop-Petticoatshoop. By these they are incommodedincommoded in their General and Particular Calling, and therefore they cannot answer the Ends of either necessary or ornamental Apparel. These monstrous topsy-turvy Mortar-Piecesmortar, are neither fit for the Church, the Hall, or the Kitchen; and if a Number of them were well mounted on Noddles-Islandnoddles, they would look more like Engines of War for bombarding the Town, than Ornaments of the Fair Sex. An honest Neighbour of mine, happening to be in Town some time since on a publick Day, inform'd me, that he saw four Gentlewomen with their Hoops half mounted in a Balcony, as they withdrew to the Wall, to the great Terror of the Militia, who (he thinks) might attribute their irregular Volleys to the formidable Appearance of the Ladies Petticoats.

I assure you, Sir, I have but little Hopes of perswading my Sex, by this Letter, utterly to relinquish the extravagant Foolery, and Indication of Immodesty, in this monstrous Garb of their's; but I would at least desire them to lessen the Circumference of their Hoops, and leave it with them to consider, Whether they, who pay no Rates or Taxes, ought to take up more Room in the King's High-Way, than the Men, who yearly contribute to the Support of the Government. I am, Sir, Your Humble Servant,

SILENCE DOGOOD.

June 25, 1722 [No. 7] Give me the Muse, whose generous Force, Impatient of the Reins, Pursues an unattempted Course, Breaks all the Criticks Iron Chains. Watts.watts To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

It has been the Complaint of many Ingenious Foreigners, who have travell'd amongst us, That good Poetry is not to be expected in New-England. I am apt to Fancy, the Reason is, not because our Countreymen are altogether void of a Poetical Genius, nor yet because we have not those Advantages of Education which other Countries have, but purely because we do not afford that Praise and Encouragement which is merited, when any thing extraordinary of this Kind is produc'd among us: Upon which Consideration I have determined, when I meet with a Good Piece of New-England Poetry, to give it a suitable Encomiumencomium, and thereby endeavour to discover to the World some of its Beautys, in order to encourage the Author to go on, and bless the World with more, and more Excellent Productions.

There has lately appear'd among us a most Excellent Piece of Poetry, entituled, An Elegy upon the much Lamented Death of Mrs. Mehitebell Kitel, Wife of Mr. John Kitel of Salem, &c. It may justly be said in its Praise, without Flattery to the Author, that it is the most Extraordinary Piece that ever was wrote in New-England. The Language is so soft and Easy, the Expression so moving and pathetick, but above all, the Verse and Numbers so Charming and Natural, that it is almost beyond Comparison,

The Muse disdains Those Links and Chains, Measures and Rules of vulgar Strains, And o'er the Laws of Harmony a Sovereign Queen she reigns.I find no English Author, Ancient or Modern, whose Elegies may be compar'd with this, in respect to the Elegance of Stile, or Smoothness of Rhime; and for the affecting Part, I will leave your Readers to judge, if ever they read any Lines, that would sooner make them draw their Breath and Sigh, if not shed Tears, than these following.

Come let us mourn, for we have lost a Wife, a Daughter, and a Sister, Who has lately taken Flight, and greatly we have mist her.In another Place,

Some little Time before she yielded up her Breath, She said, I ne'er shall hear one Sermon more on Earth. She kist her Husband some little Timebefore she expir'd, Then lean'd her Head the Pillow on, just out of Breath and tir'd.But the Threefold Appellationappellation in the first Line

a Wife, a Daughter, and a Sister,must not pass unobserved. That Line in the celebrated Watts,

Gunston the Just, the Generous, and the Young,is nothing Comparable to it. The latter only mentions three Qualifications of one Person who was deceased, which therefore could raise Grief and Compassion but for One. Whereas the former, (our most excellent Poet) gives his Reader a Sort of an Idea of the Death of Three Persons, viz.

a Wife, a Daughter, and a Sister,which is Three Times as great a Loss as the Death of One, and consequently must raise Three Times as much Grief and Compassion in the Reader.

I should be very much straitned for Room, if I should attempt to discover even half the Excellencies of this Elegy which are obvious to me. Yet I cannot omit one Observation, which is, that the Author has (to his Honour) invented a new Species of Poetry, which wants a Name, and was never before known. His Muse scorns to be confin'd to the old Measures and Limits, or to observe the dull Rules of Criticks;

Nor Rapinrapin gives her Rules to fly, nor Purcellpurcell Notes to sing. Watts.Now 'tis Pity that such an Excellent Piece should not be dignify'd with a particular Name; and seeing it cannot justly be called, either Epic, Sapphic, Lyric, or Pindaricgreekstyle, nor any other Name yet invented, I presume it may, (in Honour and Remembrance of the Dead) be called the Kitelickitelic. Thus much in the Praise of Kitelic Poetry.

It is certain, that those Elegies which are of our own Growth, (and our Soil seldom produces any other sort of Poetry) are by far the greatest part, wretchedly Dull and Ridiculous. Now since it is imagin'd by many, that our Poets are honest, well-meaning Fellows, who do their best, and that if they had but some Instructions how to govern Fancy with Judgment, they would make indifferent good Elegies; I shall here subjoinsubjoin a Receiptreceipt for that purpose, which was left me as a Legacy, (among other valuable Rarities) by my Reverend Husband. It is as follows,

A RECEIPT to make a New-England Funeral ELEGY.For the Title of your Elegy. Of these you may have enough ready made to your Hands; but if you should chuse to make it your self, you must be sure not to omit the Words Aetatis Suaeaetatis, which will Beautify it exceedingly.

For the Subject of your Elegy. Take one of your Neighbours who has lately departed this Life; it is no great matter at what Age the Party dy'd, but it will be best if he went away suddenly, being Kill'd, Drown'd, or Froze to Death.

Having chose the Person, take all his Virtues, Excellencies, &c. and if he have not enough, you may borrow some to make up a sufficient Quantity: To these add his last Words, dying Expressions, &c. if they are to be had; mix all these together, and be sure you strain them well. Then season all with a Handful or two of Melancholly Expressions, such as, Dreadful, Deadly, cruel cold Death, unhappy Fate, weeping Eyes, &c. Have mixed all these Ingredients well, put them into the empty Scullscull of some young Harvard; (but in Case you have ne'er a One at Hand, you may use your own,) there let them Ferment for the Space of a Fortnight, and by that Time they will be incorporated into a Body, which take out, and having prepared a sufficient Quantity of double Rhimes, such as, Power, Flower; Quiver, Shiver; Grieve us, Leave us; tell you, excel you; Expeditions, Physicians; Fatigue him, Intrigue him; &c. you must spread all upon Paper, and if you can procure a Scrap of Latin to put at the End, it will garnish it mightily; then having affixed your Name at the Bottom, with a Moestus Composuitmoestus, you will have an Excellent Elegy.

N.B.notabene This Receipt will serve when a Female is the Subject of your Elegy, provided you borrow a greater Quantity of Virtues, Excellencies, &c. Sir, Your Servant,

Silence Dogood

p.s. I shall make no other Answer to Hypercarpus's Criticism on my last Letterhypercarpus than this, Mater me genuit, peperit mox filia matrem.mater.

July 9, 1722 [No. 8] To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

I prefer the following Abstract from the London Journal to any Thing of my own, and therefore shall present it to your Readers this week without any further Preface.

"Without Freedom of Thought, there can be no such Thing as Wisdom; and no such Thing as publick Liberty, without Freedom of Speech; which is the Right of every Man, as far as by it, he does not hurt or controul the Right of another: And this is the only Check it ought to suffer, and the only Bounds it ought to know.

"This sacred Privilege is so essential to free Goverments, that the Security of Property, and the Freedom of Speech always go together; and in those wretched Countries where a Man cannot call his Tongue his own, he can scarce call any Thing else his own. Whoever would overthrow the Liberty of a Nation, must begin by subduing the Freeness of Speech; a Thing terrible to Publick Traytors.

"This Secret was so well known to the Court of King Charles the Firstcharles, that his wicked Ministry procured a Proclamation, to forbid the People to talk of Parliaments, which those Traytors had laid aside. To assert the undoubted Right of the Subject, and defend his Majesty's legal Prerogative, was called Disaffectiondisaffection, and punished as Seditionsedition. Nay, People were forbid to talk of Religion in their Families: For the Priests had combined with the Ministers to cook up Tyranny, and suppress Truth and the Law, while the late King Jamesjames, when Duke of York, went avowedly to Mass, Men were fined, imprisoned and undone, for saying he was a Papistpapist: And that King Charles the Secondcharlesii might live more securely a Papist, there was an Act of Parliament made, declaring it Treason to say that he was one.

"That Men ought to speak well of their Governours is true, while their Governours deserve to be well spoken of; but to do publick Mischief, without hearing of it, is only the Prerogative and Felicityfelicity of Tyranny: A free People will be shewing that they are so, by their Freedom of Speech.

"The Administration of Government, is nothing else but the Attendance of the Trustees of the People upon the Interest and Affairs of the People: And as it is the Part and Business of the People, for whose Sake alone all publick Matters are, or ought to be transacted, to see whether they be well or ill transacted; so it is the Interest, and ought to be the Ambition, of all honest Magistrates, to have their Deeds openly examined, and publickly scann'd: Only the wicked Governours of Men dread what is said of them; Audivit Tiberius probra queis lacerabitur, atque perculsus estaudivit. The publick Censure was true, else he had not felt it bitter.

Freedom of Speech is ever the Symptom, as well as the Effect of a good Government. In old Rome, all was left to the Judgment and Pleasure of the People, who examined the publick Proceedings with such Discretion, and censured those who administred them with such Equity and Mildness, that in the space of Three Hundred Years, not five publick Ministers suffered unjustly. Indeed whenever the Commons proceeded to Violence, the great Ones had been the Agressors.

"Guilt only dreads Liberty of Speech, which drags it out of its lurking Holes, and exposes its Deformity and Horrour to Daylight." Horatius, Valeriusvalerius, Cincinnatuscincinnatus, and other vertuous and undesigning Magistrates of the Roman Commonwealth, had nothing to fear from Liberty of Speech. Their virtuous Administration, the more it was examin'd, the more it brightned and gain'd by Enquiry. When Valerius in particular, was accused upon some slight grounds of affecting the Diademdiadem; he, who was the first Minister of Rome, does not accuse the People for examining his Conduct, but approved his Innocence in a Speech to them; and gave such Satisfaction to them, and gained such Popularity to himself, that they gave him a new Name; inde cognomen factum Publicolae estcognomen; to denote that he was their Favourite and their Friend. Latae deinde leges — Ante omnes de provocatione Adversus Magistratus Ad Populum, Livii, lib. 2. Cap. 8.livytrans

"But Things afterwards took another Turn. Rome, with the Loss of its Liberty, lost also its Freedom of Speech; then Mens Words began to be feared and watched; and then first began the poysonous Race of Informers, banished indeed under the righteous Administration of Titus, Narva, Trajan, Aurelius, &c. but encouraged and enriched under the vile Ministry of Sejanus, Tigillinus, Pallas, and Cleander: Queri libet, quod in secreta nostra non inquirant principes, nisi quos Odimus, says Pliny to Trajanplinytrans.

"The best Princes have ever encouraged and promoted Freedom of Speech; they know that upright Measures would defend themselves, and that all upright Men would defend them. Tacitustacitus, speaking of the Reign of some of the Princes abovemention'd, says with Extasy, Rara Temporum felicitate, ubi sentire quae velis, & quae sentias dicere licetA blessed Time when you might think what you would, and speak what you thought.

"I doubt not but old Spencer and his Son, who were the Chief Ministers and Betrayers of Edward the Secondedwardii, would have been very glad to have stopped the Mouths of all the honest Men in England. They dreaded to be called Traytors, because they were Traytors. And I dare say, Queen Elizabeth's Walsinghamwalsingham, who deserved no Reproaches, feared none. Misrepresentation of publick Measures is easily overthrown, by representing publick Measures truly; when they are honest, they ought to be publickly known, that they may be publickly commended; but if they are knavishknavish or perniciouspernicious, they ought to be publickly exposed, in order to be publickly detested." Yours, &c.,

SILENCE DOGOOD.

July 23, 1722 [No. 9] Corruptio optimi est pessimacorruptio. To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

It has been for some Time a Question with me, Whether a Commonwealth suffers more by hypocritical Pretenders to Religion, or by the openly Profaneprofane? But some late Thoughts of this Nature, have inclined me to think, that the Hypocrite is the most dangerous Person of the Two, especially if he sustains a Post in the Government, and we consider his Conduct as it regards the Publick. The first Artificeartifice of a State Hypocrite is, by a few savoury Expressions which cost him Nothing, to betray the best Men in his Country into an Opinion of his Goodness; and if the Country wherein he lives is noted for the Purity of Religion, he the more easily gains his End, and consequently may more justly be expos'd and detested. A notoriously profane Person in a private Capacity, ruins himself, and perhaps forwards the Destruction of a few of his Equals; but a publick Hypocrite every day deceives his betters, and makes them the Ignorant Trumpeterstrumpeters of his supposed Godliness: They take him for a Saint, and pass him for one, without considering that they are (as it were) the Instruments of publick Mischief out of Conscience, and ruin their Country for God's sake.

This Political Description of a Hypocrite, may (for ought I know) be taken for a new Doctrine by some of your Readers; but let them consider, that a little Religion, and a little Honesty, goes a great way in Courts. 'Tis not inconsistent with Charity to distrust a Religious Man in Power, tho' he may be a good Man; he has many Temptations "to propagate publick Destruction for Personal Advantages and Security": And if his Natural Temper be covetous, and his Actions often contradict his pious Discourse, we may with great Reason conclude, that he has some other Design in his Religion besides barely getting to Heaven. But the most dangerous Hypocrite in a Common-Wealth, is one who leaves the Gospel for the sake of the Law: A Man compounded of Law and Gospel, is able to cheat a whole Country with his Religion, and then destroy them under Colour of Lawcolour: And here the Clergy are in great Danger of being deceiv'd, and the People of being deceiv'd by the Clergy, until the Monster arrives to such Power and Wealth, that he is out of the reach of both, and can oppress the People without their own blind Assistance. And it is a sad Observation, that when the People too late see their Error, yet the Clergy still persist in their Encomiumsencomium2 on the Hypocrite; and when he happens to die for the Good of his Country, without leaving behind him the Memory of one good Action, he shall be sure to have his Funeral Sermon stuff'd with Pious Expressions which he dropt at such a Time, and at such a Place, and on such an Occasion; than which nothing can be more prejudicial to the Interest of Religion, nor indeed to the Memory of the Person deceas'd. The Reason of this Blindness in the Clergy is, because they are honourably supported (as they ought to be) by their People, and see nor feel nothing of the Oppression which is obvious and burdensome to every one else.

But this Subject raises in me an Indignationindignation not to be born; and if we have had, or are like to have any Instances of this Nature in New England, we cannot better manifest our Love to Religion and the Country, than by setting the Deceivers in a true Light, and undeceiving the Deceived, however such Discoveries may be represented by the ignorant or designing Enemies of our Peace and Safety.

I shall conclude with a Paragraph or two from an ingenious Political Writer in the London Journal, the better to convince your Readers, that Publick Destruction may be easily carry'd on by hypocritical Pretenders to Religion.

"A raging Passion for immoderate Gain had made Men universally and intensely hard-hearted: They were every where devouring one another. And yet the Directors and their Accomplices, who were the acting Instruments of all this outrageous Madness and Mischief, set up for wonderful pious Persons, while they were defying Almighty God, and plundering Men; and they set apart a Fund of Subscriptions for charitable Uses; that is, they mercilessly made a whole People Beggars, and charitably supported a few necessitous and worthless Favourites. I doubt not, but if the Villany had gone on with Success, they would have had their Names handed down to Posterity with Encomiums; as the Names of other publick Robbers have been! We have Historians and Ode Makers now living, very proper for such a Task. It is certain, that most People did, at one Time, believe the Directors to be great and worthy Persons. And an honest Country Clergyman told me last Summer, upon the Road, that Sir John was an excellent publick-spirited Person, for that he had beautified his Chancelchancel.

"Upon the whole we must not judge of one another by their best Actions; since the worst Men do some Good, and all Men make fine Professions: But we must judge of Men by the whole of their Conduct, and the Effects of it. Thorough Honesty requires great and long Proof, since many a Man, long thought honest, has at length proved a Knaveknave. And it is from judging without Proof, or false Proof, that Mankind continue Unhappy." I am, Sir, Your humble Servant,

SILENCE DOGOOD.

August 13, 1722 [No. 10] Optimè societas hominum servabitur. Cic.cicerotrans2 To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

Discoursing lately with an intimate Friend of mine of the lamentable Condition of Widows, he put into my Hands a Book, wherein the ingenious Author proposes (I think) a certain Method for their Relief. I have often thought of some such Project for their Benefit my self, and intended to communicate my Thoughts to the Publick; but to prefer my own Proposals to what follows, would be rather an Argument of Vanity in me than Good Will to the many Hundreds of my Fellow-Sufferers now in New-England.

“We have (says he) abundance of Women, who have been Bred well, and Liv’d well, Ruin’d in a few Years, and perhaps, left Young, with a House full of Children, and nothing to Support them; which falls generally upon the Wives of the Inferior Clergy, or of Shopkeepers and Artificersartificer.

“They marry Wives with perhaps £300 to £1000 Portionportion, and can settle no Jointurejointure upon them; either they are Extravagant and Idle, and Waste it, or Trade decays, or Losses, or a Thousand Contingences happen to bring a Tradesman to Poverty, and he Breaks; the Poor Young Woman, it may be, has Three or Four Children, and is driven to a thousand shifts, while he lies in the Mintmint or Fryarsfryar under the Dilemma of a Statute of Bankrupt; but if he Dies, then she is absolutely Undone, unless she has Friends to go to.

“Suppose an Office to be Erected, to be call’d An Office of Ensurance for Widows, upon the following Conditions;

“Two thousand Women, or their Husbands for them, Enter their Names into a Register to be kept for that purpose, with the Names, Age, and Trade of their Husbands, with the Place of their abode, Paying at the Time of their Entring 5sbritcash. down with 1s. 4d. per Quarter, which is to the setting up and support of an Office with Clerks, and all proper Officers for the same; for there is no maintaining such without Charge; they receive every one of them a Certificate, Seal’d by the Secretary of the Office, and Sign’d by the Governors, for the Articles hereafter mentioned.

“If any one of the Women becomes a Widow, at any Time after Six Months from the Date of her Subscription, upon due Notice given, and Claim made at the Office in form, as shall be directed, she shall receive within Six Months after such Claim made, the Sum of £500 in Money, without any Deductions, saving some small Fees to the Officers, which the Trustees must settle, that they may be known.

“In Consideration of this, every Woman so Subscribing, Obliges her self to Pay as often as any Member of the Society becomes a Widow, the due Proportion or Share allotted to her to Pay, towards the £500 for the said Widow, provided her Share does not exceed the Sum of 5s.

“No Seamen or Soldiers Wives to be accepted into such a Proposal as this, on the Account before mention’d, because the Contingences of their Lives are not equal to others, unless they will admit this general Exception, supposing they do not Die out of the Kingdom.

“It might also be an Exception, That if the Widow, that Claim’d, had really, bona fidebonafide,left her by her Husband to her own use, clear of all Debts and Legacies, £2000 she shou’d have no Claim; the Intent being to Aid the Poor, not add to the Rich. But there lies a great many Objections against such an Article: As

“1. It may tempt some to forswearforswear themselves. “2. People will Order their Wills so as to defrauddefraud the Exception.“One Exception must be made; and that is, Either very unequal Matches, as when a Woman of Nineteen Marries an old Man of Seventy; or Women who have infirminfirm Husbands, I mean known and publickly so. To remedy which, Two things are to be done.

“[1.] The Office must have moving Officers without doors, who shall inform themselves of such matters, and if any such Circumstances appear, the Office should have 14 days time to return their Money, and declare their Subscriptions Void. “2. No Woman whose Husband had any visible Distemperdistemper, should claim under a Year after her Subscription.“One grand Objection against this Proposal, is, How you will oblige People to pay either their Subscription, or their Quarteridgequarteridge.

“To this I answer, By no Compulsion (tho’ that might be perform’d too) but altogether voluntary; only with this Argument to move it, that if they do not continue their Payments, they lose the Benefit of their past Contributions.

“I know it lies as a fair Objection against such a Project as this, That the number of Claims are so uncertain, That no Body knows what they engage in, when they Subscribe, for so many may die Annually out of Two Thousand, as may perhaps make my Payment £20 or 25 per Annperannum., and if a Woman happen to Pay that for Twenty Years, though she receives the £500 at last she is a great Loser; but if she dies before her Husband, she has lessened his Estate considerably, and brought a great Loss upon him.

“First, I say to this, That I wou’d have such a Proposal as this be so fair and easy, that if any Person who had Subscrib’d found the Payments too high, and the Claims fall too often, it shou’d be at their Liberty at any Time, upon Notice given, to be released and stand Oblig’d no longer; and if so, Volenti non fit Injuriaviolenti; every one knows best what their own Circumstances will bear.

“In the next Place, because Death is a Contingency, no Man can directly Calculate, and all that Subscribe must take the Hazard; yet that a Prejudice against this Notion may not be built on wrong Grounds, let’s examine a little the Probable hazard, and see how many shall die Annually out of 2000 Subscribers, accounting by the common proportion of Burials, to the number of the Living.

“Sir William Petty in his Political Arithmetick, by a very Ingenious Calculation, brings the Account of Burials in London, to be 1 in 40 Annually, and proves it by all the proper Rules of proportion’d Computation; and I’le take my Scheme from thence. If then One in Forty of all the People in England should Die, that supposes Fifty to Die every Year out of our Two Thousand Subscribers; and for a Woman to Contribute 5s. to every one, would certainly be to agree to Pay £12 10s. per Ann. upon her Husband’s Life, to receive £500 when he Di’d, and lose it if she Di’d first; and yet this wou’d not be a hazard beyond reason too great for the Gain.

“But I shall offer some Reasons to prove this to be impossible in our Case; First, Sir William Petty allows the City of London to contain about a Million of People, and our Yearly Bill of Mortality never yet amounted to 25000 in the most Sickly Years we have had, Plague Years excepted, sometimes but to 20000, which is but One in Fifty: Now it is to be consider’d here, that Children and Ancient People make up, one time with another, at least one third of our Bills of Mortality; and our Assurances lies upon none but the Midling Age of the People, which is the only age wherein Life is any thing steady; and if that be allow’d, there cannot Die by his Computation, above One in Eighty of such People, every Year; but because I would be sure to leave Room for Casualty, I’le allow one in Fifty shall Die out of our Number Subscrib’d.

“Secondly, It must be allow’d, that our Payments falling due only on the Death of Husbands, this One in Fifty must not be reckoned upon the Two thousand; for ’tis to be suppos’d at least as many Women shall die as Men, and then there is nothing to Pay; so that One in Fifty upon One Thousand, is the most that I can suppose shall claim the Contribution in a Year, which is Twenty Claims a Year at 5s. each, and is £5 per Ann. and if a Woman pays this for Twenty Year, and claims at last, she is Gainer enough, and no extraordinary Loser if she never claims at all: And I verily believe any Office might undertake to demand at all Adventures not above £6 per Ann. and secure the Subscriber £500 in case she come to claim as a Widow.”

I would leave this to the Consideration of all who are concern’d for their own or their Neighbour’s Temporaltemporal Happiness; and I am humbly of Opinion, that the Country is ripe for many such Friendly Societies, whereby every Man might help another, without any Disservice to himself. We have many charitable Gentlemen who Yearly give liberally to the Poor, and where can they better bestow their Charity than on those who become so by Providence, and for ought they know on themselves. But above all, the Clergy have the most need of coming into some such Project as this. They as well as poor Men (according to the Proverb) generally abound in Children; and how many Clergymen in the Country are forc’d to labour in their Fields, to keep themselves in a Condition above Want? How then shall they be able to leave any thing to their forsaken, dejected, and almost forgotten Wives and Children. For my own Part, I have nothing left to live on, but Contentment and a few Cows; and tho’ I cannot expect to be reliev’d by this Project, yet it would be no small Satisfaction to me to see it put in Practice for the Benefit of others. I am, Sir, &c.

SILENCE DOGOOD

August 20, 1722 [No. 11] Neque licitum interea est meam amicam visere.unknownlatin To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

From a natural Compassion to my Fellow-Creatures, I have sometimes been betray'd into Tears at the Sight of an Object of Charity, who by a bear [sic]sic Relation of his Circumstances, seem'd to demand the Assistance of those about him. The following Petition represents in so lively a Manner the forlorn State of a Virgin well stricken in Years and Repentance, that I cannot forbear publishing it at this Time, with some Advice to the Petitioner.

To Mrs. Silence Dogood.

"1. That your Petitioner being puff'd up in her younger Years with a numerous Train of Humble Servants, had the Vanity to think, that her extraordinary Wit and Beauty would continually recommend her to the Esteem of the Gallantsgallant; and therefore as soon as it came to be publickly known that any Gentleman address'd her, he was immediately discarded.

"2. That several of your Petitioners Humble Servants, who upon their being rejected by her, were, to all Apperance in a dying Condition, have since recover'd their Health, and been several Years married, to the great Surprize and Grief of your Petitioner, who parted with them upon no other Conditions, but that they should die or run distracted for her, as several of them faithfully promis'd to do.

"3. That your Petitioner finding her self disappointed in and neglected by her former Adorers, and no new Offers appearing for some Years past, she has been industriously contracting Acquaintance with several Families in Town and Country, where any young Gentlemen or Widowers have resided, and endeavour'd to appear as conversable as possible before them: She has likewise been a strict Observer of the Fashion, and always appear'd well dress'd. And the better to restore her decay'd Beauty, she has consum'd above Fifty Pound's Worthfiftylb of the most approved Cosmeticks. But all won't do.

"Your Petitioner therefore most humbly prays, That you would be pleased to form a Project for the Relief of all those penitentpenitent Mortals of the fair Sex, that are like to be punish'd with their Virginity until old Age, for the Pride and Insolence of their Youth.

"And your Petitioner (as in Duty bound) shall ever pray, &c.

Margaret Aftercast"

Were I endow'd with the Faculty of Match-making, it should be improv'd for the Benefit of Mrs. Margaret, and others in her Condition: But since my extream Modesty and Taciturnitytaciturn, forbids an Attempt of this Nature, I would advise them to relieve themselves in a Method of Friendly Society; and that already publish'd for Widows, I conceive would be a very proper Proposal for them, whereby every single Woman, upon full Proof given of her continuing a Virgin for the Space of Eighteen Years, (dating her Virginity from the Age of Twelve,) should be entituled to £500 in ready Cash.

But then it will be necessary to make the following Exceptions.

1. That no Woman shall be admitted into the Society after she is Twenty Five Years old, who has made a Practice of entertaining and discarding Humble Servants, without sufficient Reason for so doing, until she has manifested her Repentance in Writing under her Hand.

2. No Member of the Society who has declar'd before two credible Witnesses, That it is well known she has refus'd several good Offers since the Time of her Subscribing, shall be entituled to the £500 when she comes of Age; that is to say, Thirty Years.

3. No Woman, who after claiming and receiving, has had the good Fortune to marry, shall entertain any Company with Encomiumsencomium3 on her Husband, above the Space of one Hour at a Time, upon Pain of returning one half the Money into the Office, for the first Offence; and upon the second Offence to return the Remainder. I am, Sir, Your Humble Servant,

SILENCE DOGOOD

September 10, 1722 [No. 12] Quod est in cordi sobrii, est in ore ebriicordi. To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

It is no unprofitable tho' unpleasant Pursuit, diligently to inspect and consider the Manners and Conversation of Men, who, insensible of the greatest Enjoyments of humane Life, abandon themselves to Vice from a false Notion of Pleasure and good Fellowship. A true and natural Representation of any Enormity, is often the best Argument against it and Means of removing it, when the most severe Reprehensions alone, are found ineffectual.

I would in this letter improve the little Observation I have made on the Vice of Drunkeness, the better to reclaim the good Fellows who usually pay the Devotions of the Evening to Bacchusbacchus.

I doubt not but moderate Drinking has been improv'd for the Diffusion of Knowledge among the ingenious Part of Mankind, who want the Talent of a ready Utterance, in order to discover the Conceptions of their Minds in an entertaining and intelligible Manner. 'Tis true, drinking does not improve our Faculties, but it enables us to use them; and therefore I conclude, that much Study and Experience, and a little Liquor, are of absolute Necessity for some Tempers, in order to make them accomplish'd Orators. Dic. Ponder discovers an excellent Judgment when he is inspir'd with a Glass or two of Claretclaret, but he passes for a Fool among those of small Observation, who never saw him the better for Drink. And here it will not be improper to observe, That the moderate Use of Liquor, and a well plac'd and well regulated Anger, often produce this same Effect; and some who cannot ordinarily talk but in broken Sentences and false Grammar, do in the Heat of Passion express themselves with as much Eloquence as Warmth. Hence it is that my own Sex are generally the most eloquent, because the most passionate. "It has been said in the Praise of some Men, (says an ingenious Author,) that they could talk whole Hours together upon any thing; but it must be owned to the Honour of the other Sex, that there are many among them who can talk whole Hours together upon Nothing. I have known a Woman branch out into a long extemporeextempore Dissertation on the Edging of a Petticoatedging, and chidechide her Servant for breaking a China Cup, in all the Figures of Rhetorick."

But after all it must be consider'd, that no Pleasure can give Satisfaction or prove advantageous to a reasonable Mind, which is not attended with the Restraints of Reason. Enjoyment is not to be found by Excess in any sensual Gratification; but on the contrary, the immoderate Cravings of the Voluptuaryvoluptuary, are always succeeded with Loathing and a palledpalled Appetite. What Pleasure can the Drunkard have in the Reflection, that, while in his Cups, he retain'd only the Shape of a Man, and acted the Part of a Beast; or that from reasonable Discourse a few Minutes before, he descended to Impertinenceimpertinence2 and Nonsense?

I cannot pretend to account for the different Effects of Liquor on Persons of different Dispositions, who are guilty of Excess in the Use of it. 'Tis strange to see Men of a regular Conversation become rakishrakish and profane when intoxicated with Drink, and yet more surprizing to observe, that some who appear to be the most profligateprofligate Wretches when sober, become mighty religious in their Cups, and will then, and at no other Time address their Maker, but when they are destitute of Reason, and actually affrontingaffront him. Some shrink in the Wettingwetting, and others swell to such an unusual Bulk in their Imaginations, that they can in an Instant understand all Arts and Sciences, by the liberal Education of a little vivifyingvivifying Punch, or a sufficient Quantity of other exhilerating Liquor.

And as the Effects of Liquor are various, so are the Characters given to its Devourers. It argues some Shame in the Drunkards themselves, in that they have invented numberless Words and Phrases to cover their Folly, whose proper Significations are harmless, or have no Signification at all. They are seldom known to be drunk, tho' they are very often boozey, cogey, tipsey, fox'd, merry, mellow, fuddl'd, groatable, Confoundedly cut, See two Moons, are Among the Philistines, In a very good Humour, See the Sun, or, The Sun has shone upon them; they Clip the King's English, are Almost froze, Feavourish, In their Altitudes, Pretty well enter'd, &cdrunk. In short, every Day produces some new Word or Phrase which might be added to the Vocabulary of the Tiplerstipler: But I have chose to mention these few, because if at any Time a Man of Sobriety and Temperance happens to cut himself confoundedly, or is almost froze, or feavourish, or accidentally sees the Sun, &c. he may escape the Imputationimputation of being drunk, when his Misfortune comes to be related. I am Sir, Your Humble Servant,

SILENCE DOGOOD

September 24, 1722 [No. 13] To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

In Persons of a contemplative Disposition, the most indifferent Things provoke the Exercise of the Imagination; and the Satisfactions which often arise to them thereby, are a certain Relief to the Labour of the Mind (when it has been intensely fix'd on more substantial Subjects) as well as to that of the Body.

In one of the late pleasant Moon-light Evenings, I so far indulg'd in my self the Humour of the Town in walking abroad, as to continue from my Lodgings two or three Hours later than usual, and was pleas'd beyond Expectation before my Return. Here I found various Company to observe, and various Discourse to attend to. I met indeed with the common Fate of Listeners, (who hear no good of themselves,) but from a Consciousness of my Innocence, receiv'd it with a Satisfaction beyond what the Love of Flattery and the Daubingsdaubing of a Parasite could produce. The Company who rally'd me were about Twenty in Number, of both Sexes; and tho' the Confusion of Tongues (like that of Babel) which always happens among so many impetuousimpetuous Talkers, render'd their Discourse not so intelligible as I could wish, I learnt thus much, That one of the Females pretended to know me, from some Discourse she had heard at a certain House before the Publication of one of my Letters; adding, That I was a Person of an ill Character, and kept a criminal Correspondence with a Gentleman who assisted me in Writing. One of the Gallantsgallant2 clear'd me of this random Charge, by saying, That tho' I wrote in the Character of a Woman, he knew me to be a Man; But, continu'd he, he has more need of endeavouring a Reformation in himself, than spending his Wit in satyrizing others.

I had no sooner left this Set of Ramblersrambler, but I met a Crowd of Tarpolinstarpolins and their Doxiesdoxies, link'd to each other by the Arms, who ran (by their own Account) after the Rate of Six Knots an Hourknot, and bent their Course towards the Common. Their eager and amorous Emotions of Body, occasion'd by taking their Mistresses in Tow, they call'd wild Steeragesteerage: And as a Pair of them happen'd to trip and come to the Ground, the Company were call'd upon to bring to, for that Jack and Betty were founder'd. But this Fleet were not less comical or irregular in their Progress than a Company of Females I soon after came up with, who, by throwing their Heads to the Right and Left, at every one who pass'd by them, I concluded came out with no other Design than to revive the Spirit of Love in Disappointed Batchelors, and expose themselves to Sale to the first Bidder.

But it would take up too much Room in your Paper to mention all the Occasions of Diversion I met with in this Night's Rambleramble. As it grew later, I observed, that many pensive Youths with down Looks and a slow Pace, would be ever now and then crying out on the Cruelty of their Mistresses; others with a more rapid Pace and chearful Air, would be swinging their Canes and clapping their Cheeks, and whispering at certain Intervals, I'm certain I shall have her! This is more than I expected! How charmingly she talks! &c.

Upon the whole I conclude, That our Night-Walkers are a Set of People, who contribute very much to the Health and Satisfaction of those who have been fatigu'd with Business or Study, and occasionally observe their pretty Gestures and Impertinenciesimpertinence3. But among Men of Business, the Shoemakers, and other Dealers in Leather, are doubly oblig'd to them, inasmuch as they exceedingly promote the Consumption of their Ware: And I have heard of a Shoemaker, who being ask'd by a noted Rambler, Whether he could tell how long her Shoes would last; very prettily answer'd, That he knew how many Days she might wear them, but not how many Nights; because they were then put to a more violent and irregular Service than when she employ'd her self in the common Affairs of the House. I am, Sir, Your Humble Servant,

SILENCE DOGOOD

October 8, 1722 [No. 14] Earum causarum quantum quaeque valeat, videamus. Cicerocicerotrans3. To the Author of the New-England Courant.Sir,

It often happens, that the most zealous Advocates for any Cause find themselves disappointed in the first Appearance of Success in the Propagation of their Opinion; and the Disappointment appears unavoidable, when their easy Proselytesproselyte too suddenly start into Extreams, and are immediately fill'd with Arguments to invalidate their former Practice. This creates a Suspicion in the more considerate Part of Mankind, that those who are thus given to Change, neither fear God, nor honour the King. In Matters of Religion, he that alters his Opinion on a religious Account, must certainly go thro' much Reading, hear many Arguments on both Sides, and undergo many Struggles in his Conscience, before he can come to a full Resolution: Secular Interest will indeed make quick Work with an immoral Man, especially if, notwithstanding the Alteration of his Opinion, he can with any Appearance of Credit retain his Immorality. But, by this Turn of Thought I would not be suspected of Uncharitableness to those Clergymen at Connecticut, who have lately embrac'd the Establish'd Religion of our Nation, some of whom I hear made their Professions with a Seriousness becoming their Order: However, since they have deny'd the Validity of Ordination by the Hands of Presbyters, and consequently their Power of Administring the Sacraments, &c. we may justly expect a suitable Manifestation of their Repentance for invading the Priests Office, and living so long in a Corah-likecorah Rebellion. All I would endeavour to shew is, That an indiscreet Zeal for spreading an Opinion, hurts the Cause of the Zealot. There are too many blind Zealots among every Denomination of Christians; and he that propagates the Gospel among Rakesrake and Beausbeau without reforming them in their Morals, is every whit as ridiculous and impolitick as a Statesman who makes Tools of Ideots and Tale-Bearersgossip.

Much to my present Purpose are the Words of two Ingenious Authors of the Church of England, tho' in all Probability they were tainted with Whiggishwhiggish Principles; and with these I shall conclude this Letter.

"I would (says one) have every zealous Man examine his Heart thoroughly, and, I believe, he will often find that what he calls a Zeal for his Religion, is either Pride, Interest or Ill-nature. A Man who differs from another in Opinion sets himself above him in his own Judgment, and in several Particulars pretends to be the wiser Person. This is a great Provocation to the Proud Man, and gives a keen Edge to what he calls his Zeal. And that this is the Case very often, we may observe from the Behaviour of some of the most Zealous for Orthodoxy, who have often great Friendships and Intimacies with vicious immoral Men, provided they do but agree with them in the same Scheme of Belief. The Reason is, because the vicious Believer gives the Precedency to the virtuous Man, and allows the good Christian to be the worthier Person, at the same Time that he cannot come up to his Perfections. This we find exemplified in that trite Passage which we see quoted in almost every System of Ethicks, tho' upon another Occasion;

--Video meliore proboque Deteriora sequor-- ovidtrans