Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World ["Gulliver's

Travels"]

By

Jonathan Swift

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students of The University of Virginia

Audio

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverDampierWilliam Dampier (1651-1715), English

explorer and pirate whose memoir A New Voyage Round the

World (1697), told the story of his adventures, including one of

the first European accounts of the island of Australia. SmithfieldLarge open space in central London that, among other

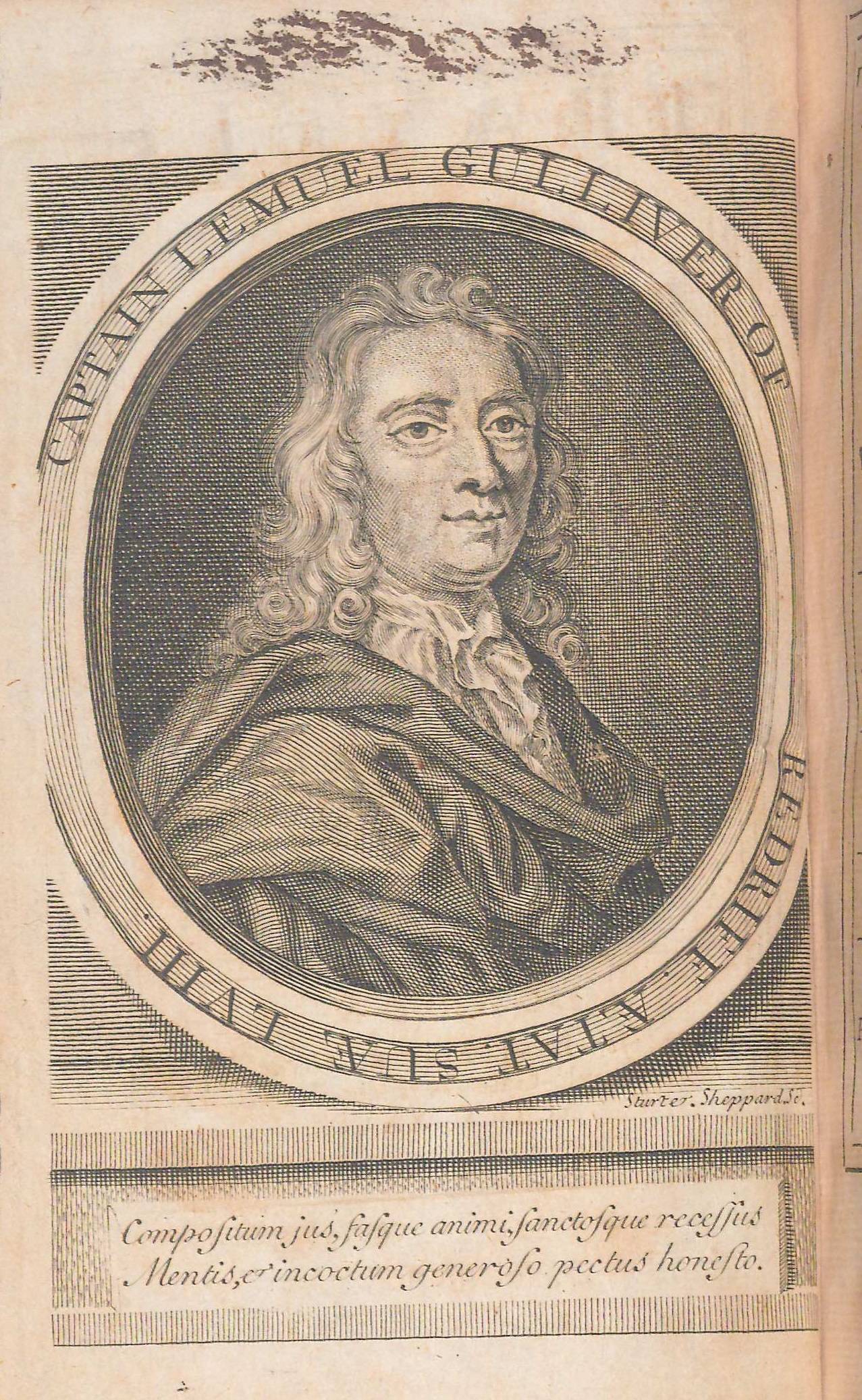

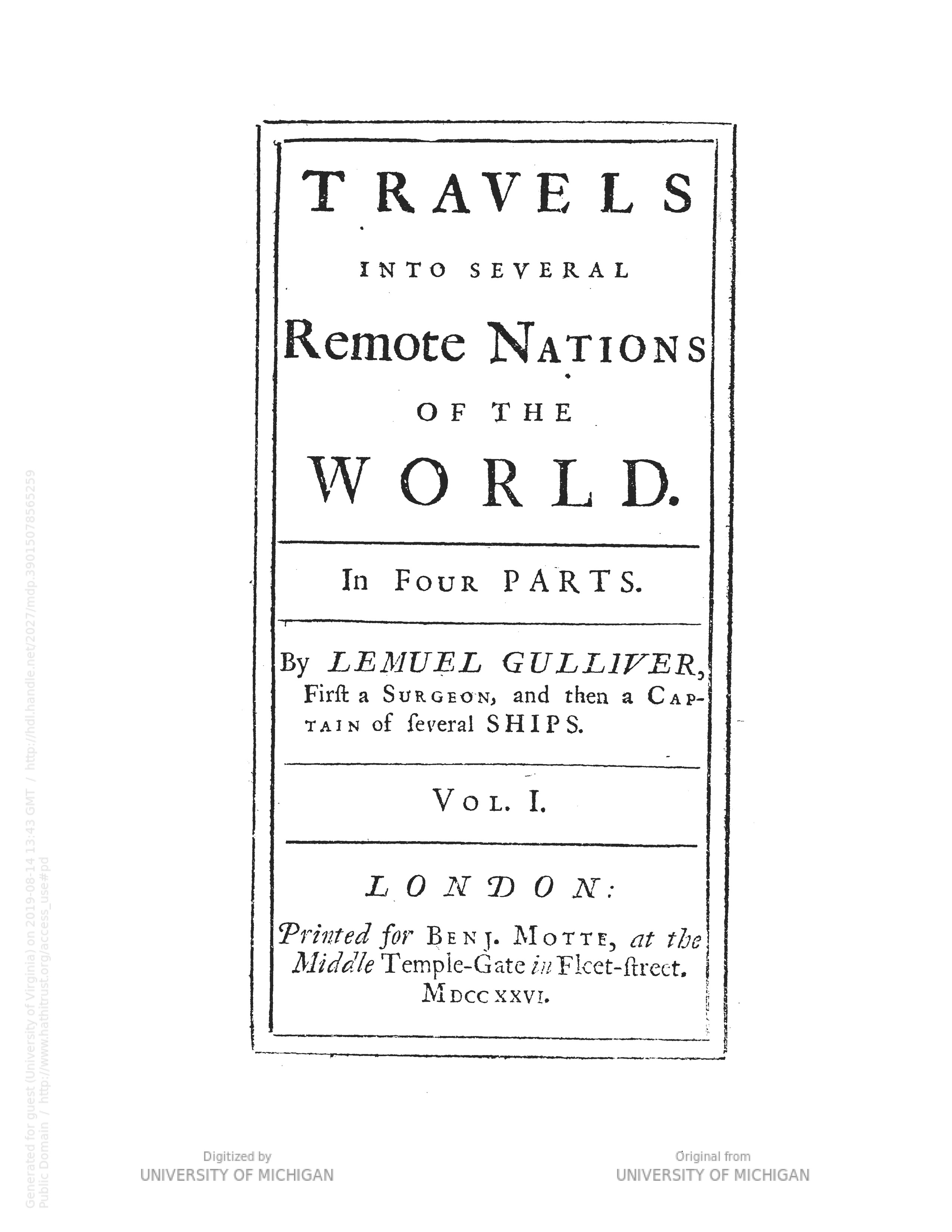

things, was famous for the annual Bartholomew Fair in the summer.TravelsWhen it was

first published in 1726, the book that we have come to call Gulliver’s Travels appeared, without any advance

notice or fanfare, on the shelves of London booksellers under the title

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the

World. The author was identified as “Lemuel Gulliver, first a

Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships." The name Jonathan Swift

appeared nowhere on the book; rather, “Lemuel Gulliver" was portrayed in

a frontispiece portrait that identified him as being fifty-eight years

old and a resident of Redriff, a village on the Thames river to the

southeast of London. Below the portrait appears a Latin quote from the

second Satire of the classical poet Persius, that translates as

something like "justice, uprightness, and nobility of soul, in the

sacred places of the mind, with a heart filled with generous honor,"

endorsing Gulliver as a man who could be believed. Redriff would also be

logical place for a retired seaman to be living, and details like this,

along with the frontispiece portrait, confer a sense of realism on the

book that follows. But of course there was no Lemuel Gulliver; the image

is a fake, the first of the many hoaxes that would follow. And by

quoting Persius (without identifying him as the author), the

frontispiece also might tip the savvy reader off to the fact that the

work it prefaces is a satire.

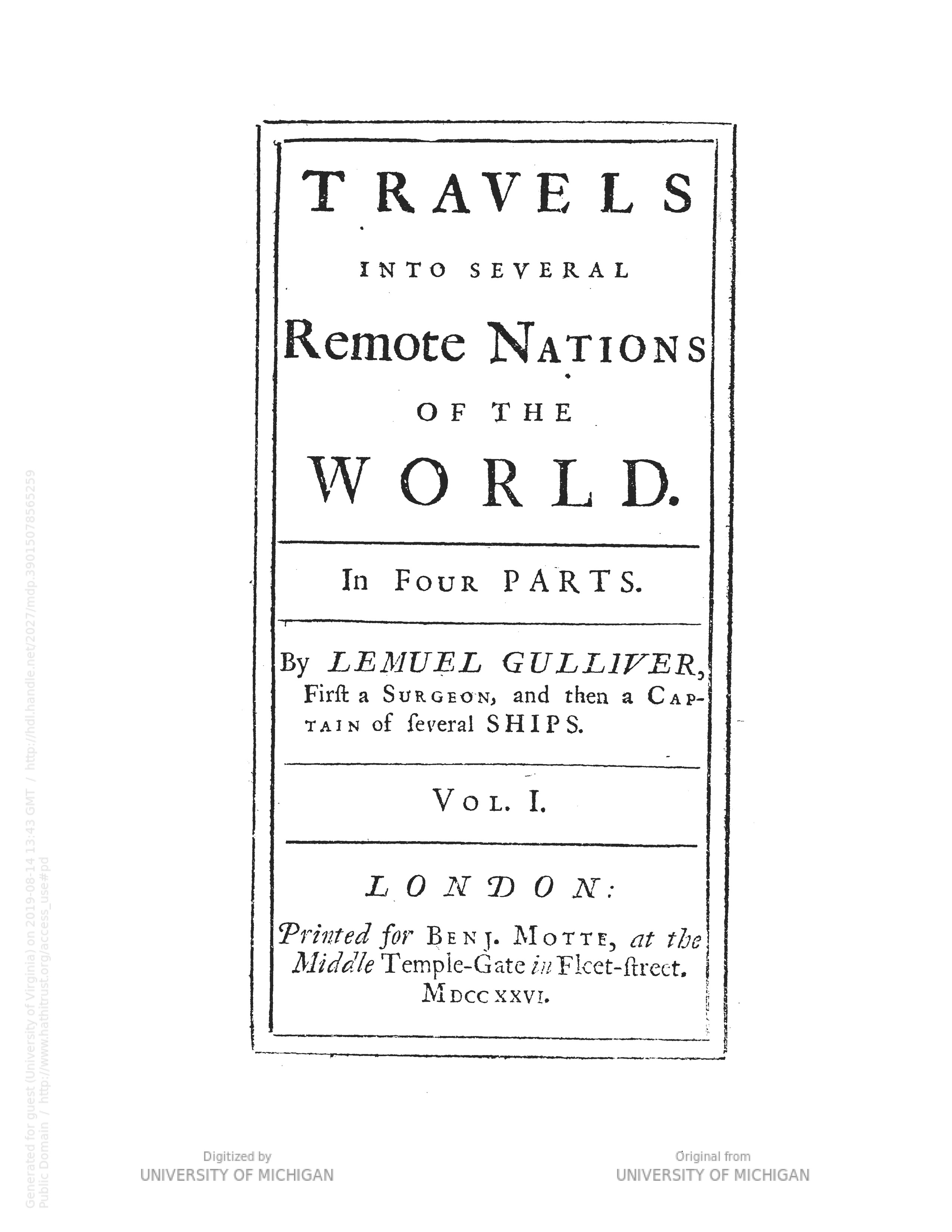

Source: Title page of first edition

Source: Title page of first edition

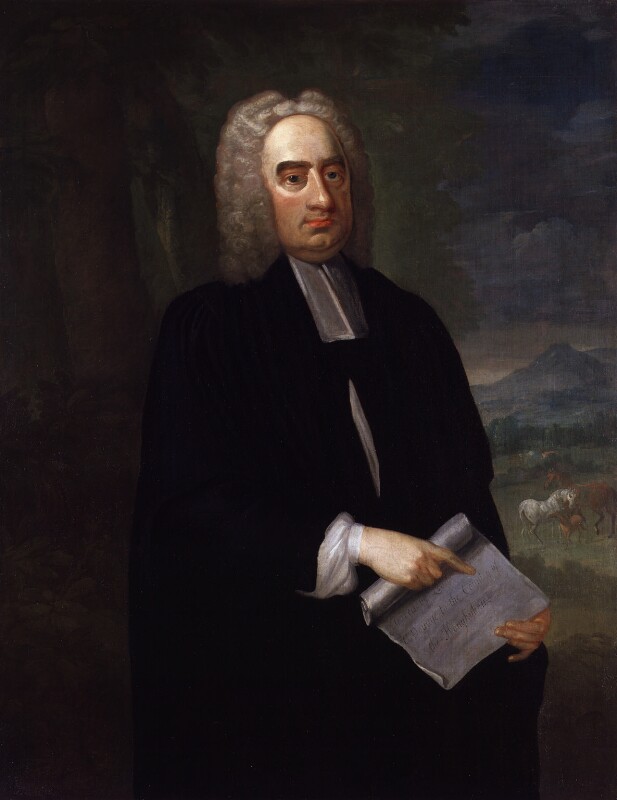

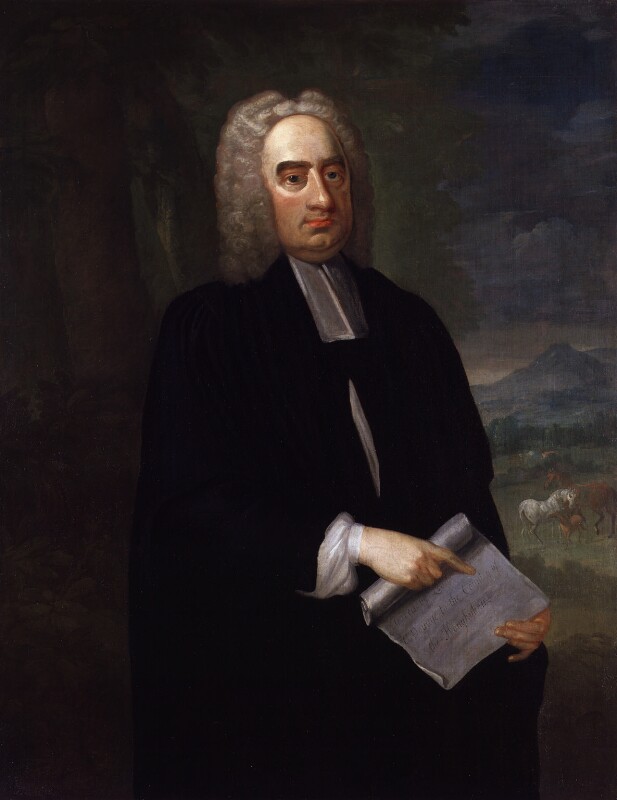

There was no one quite like the book’s real author, Jonathan Swift, either. He was born in Ireland in 1667 to a family that was a part of the wave of English people who went there in that period, English Protestants who were encouraged to emigrate and take positions in Irish institutions in order to bind that island more tightly to English domination. Almost all biographical accounts state that his father, also named Jonathan Swift, died seven months before he was born. But there is no documentary evidence for that, or for his parents’ marriage, the date of his father’s death, or even for Swift’s baptism. Swift’s most recent biographer, Leo Damrosch, suggests that his real father may have been Sir John Temple, a wealthy English nobleman who was living in Ireland at the time and who knew Swift’s mother and her family. There is no way of proving this, and we will probably never know one way or the other. But if Sir John Temple were Swift's father, that would explain some things, such as how Swift would become the private secretary to William Temple, Sir John Temple’s son. Swift, who had an undistinguished career as a student at Trinity College in Dublin, would not have been an obvious choice, and he seems not to have met William Temple before he began working for him. Again, we will probably never be certain of the truth here, and Swift seems to have cultivated a certain amount of mystery about his private life. Although we know, for example, that he had intimate friendships with several women, notably Esther Johnson (to whom he gave the name “Stella") and Esther Vanhomrigh (who he referred to as Vanessa, a name that he invented), the full nature of these relationships eluded, even mystified people then, and frustrates us now. (Some people believed that Swift and Stella had been secretly married; others thought that idea was ridiculous.) Friends found him to be witty and generous, but he could also be demanding and moody. He suffered for much of his life from Meniere’s disease, a disorder where fluid builds up in the inner ear. The condition sometimes left him bedridden for days as he dealt with intense vertigo and nausea; he eventually went deaf. Satirists are often outsiders, and it is not hard to imagine how Swift might have felt himself to be an outsider to his society, set apart by his birth and his health to be an ironic observer as often as a full participant.

Source: Portrait of Jonathan Swift by Francis Bindon, c. 1735, National Portrait Gallery, London

Gulliver's Travels was immediately a hit with

readers, and it did not take long for its real author to be identified,

even though Swift publicly stayed silent about his role for several

years. The book was translated into French and other European languages

very early on; theatrical versions, some with children playing the

Lilliputians, were on the stage in London within a few years. Gulliver's

adventures, particularly his experiences with the small but ruthless

Lilliputians and the large but gentle Brobdignagians, have become myths

of the modern world, stories that everyone knows the general outlines of

even if they have never opened the book. But fully grasping what Swift

was up to has proven to be a challenge. Swift provided no gloss on his

own work, and the book defies an easy moral or satisfying conclusion.

What, exactly, are we to make of the Houyhnhnms, the intelligent horses

of book IV? They seem have come up with the kind of minimal, direct mode

of governance that Swift, in other writings, often advocated. But they

are also able to contemplete genocide, casually thinking of

exterminating all the Yahoos, a fact that Gulliver does not comment

upon. What do all of the encounters of Book III, where Gulliver visits a

series of miserable projectors of various kinds, add up to, if anything?

Who is this Gulliver, anyway, and what kind of character are we dealing

with? Swift plays with, defies, and undercuts our expectations for what

either a truthful travel narrative or a fictional story should be. Gulliver's Travels is one of the greatest books

in English from the eighteenth century.

Source: Portrait of Jonathan Swift by Francis Bindon, c. 1735, National Portrait Gallery, London

Gulliver's Travels was immediately a hit with

readers, and it did not take long for its real author to be identified,

even though Swift publicly stayed silent about his role for several

years. The book was translated into French and other European languages

very early on; theatrical versions, some with children playing the

Lilliputians, were on the stage in London within a few years. Gulliver's

adventures, particularly his experiences with the small but ruthless

Lilliputians and the large but gentle Brobdignagians, have become myths

of the modern world, stories that everyone knows the general outlines of

even if they have never opened the book. But fully grasping what Swift

was up to has proven to be a challenge. Swift provided no gloss on his

own work, and the book defies an easy moral or satisfying conclusion.

What, exactly, are we to make of the Houyhnhnms, the intelligent horses

of book IV? They seem have come up with the kind of minimal, direct mode

of governance that Swift, in other writings, often advocated. But they

are also able to contemplete genocide, casually thinking of

exterminating all the Yahoos, a fact that Gulliver does not comment

upon. What do all of the encounters of Book III, where Gulliver visits a

series of miserable projectors of various kinds, add up to, if anything?

Who is this Gulliver, anyway, and what kind of character are we dealing

with? Swift plays with, defies, and undercuts our expectations for what

either a truthful travel narrative or a fictional story should be. Gulliver's Travels is one of the greatest books

in English from the eighteenth century.

- [JOB]Audio1

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverinducementsInducements are something that persuades or leads

someone to take a course of action.

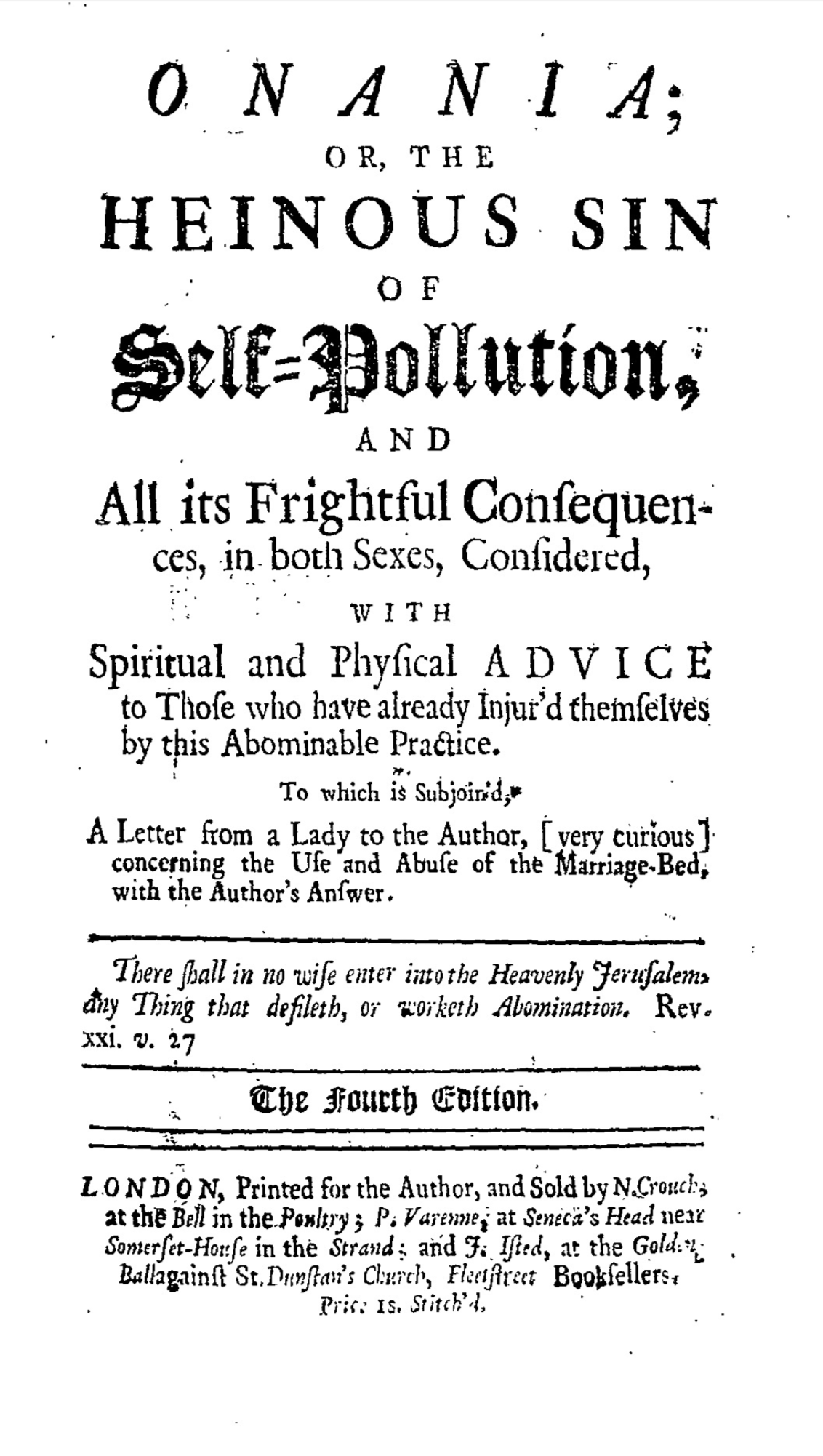

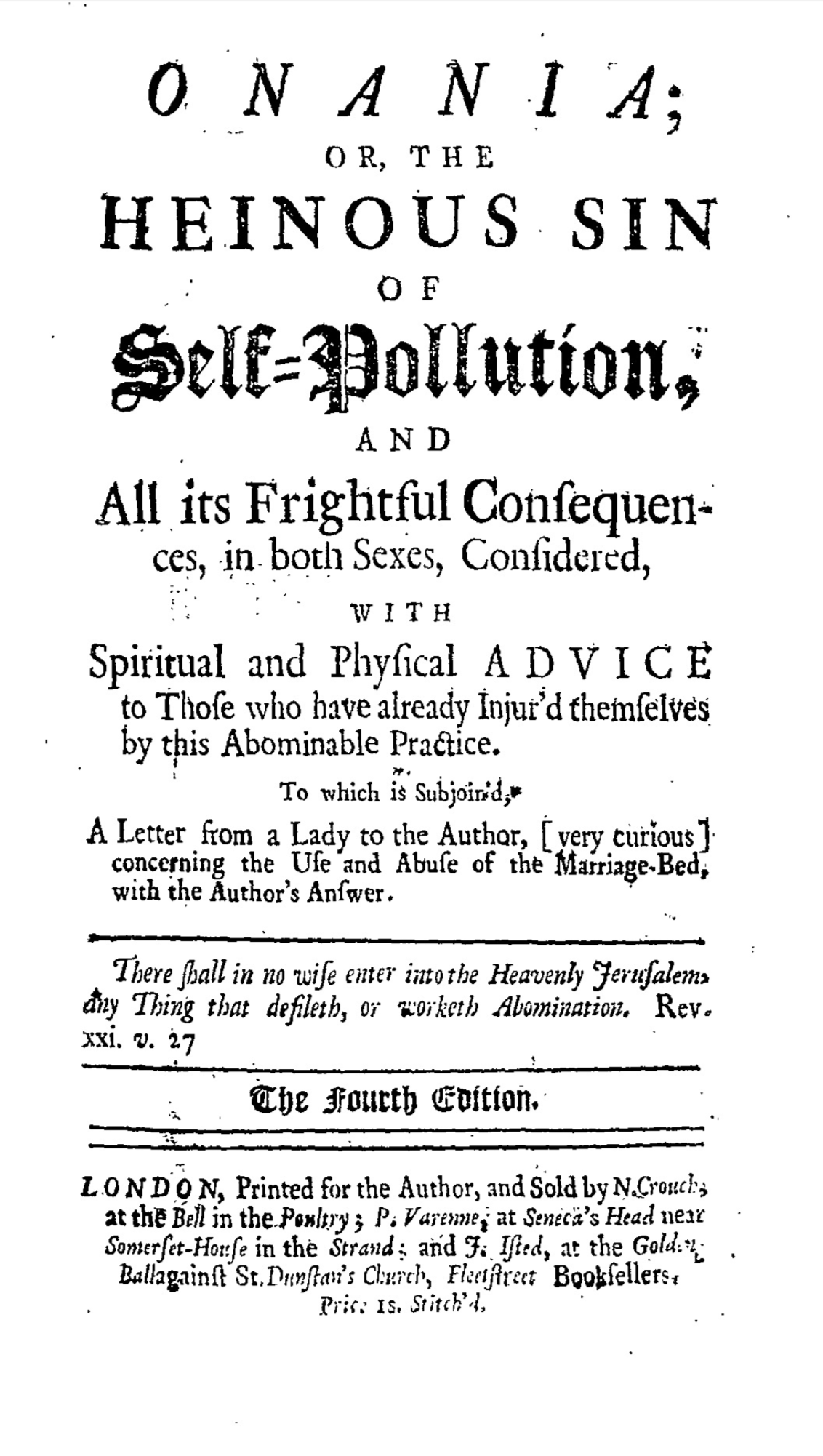

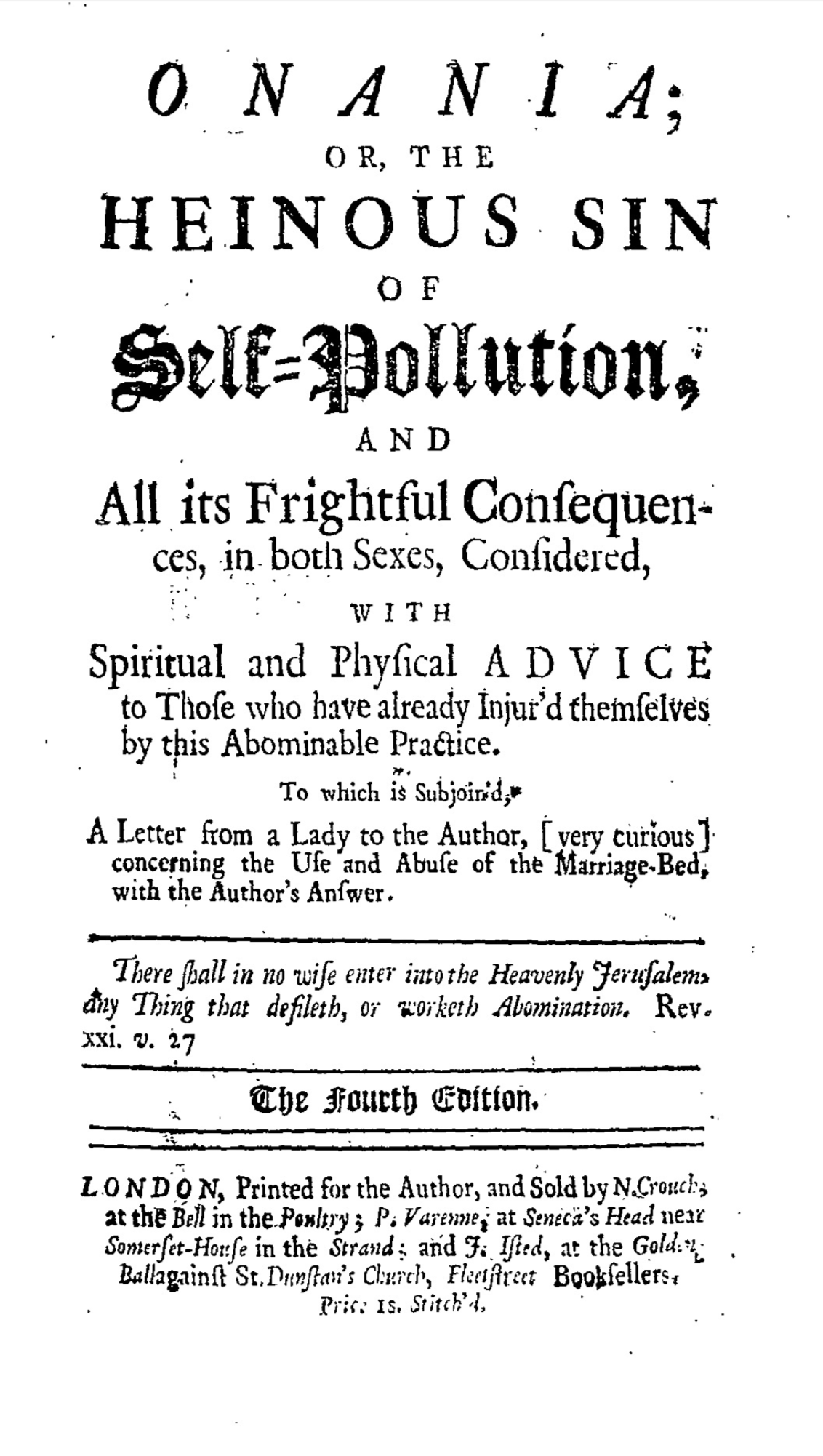

Source: Oxford English Dictionary.NottinghamshireNottinghamshire is a county in the English Midlands, about 125 miles north of London. There is probably no special significance attached to the fact that Gulliver comes from there, which may be part of the point; this is as nondescript and middle-of-the-road kind of place for the protagonist of a story to have come from. Gulliver is, in every way, an unremarkable person. - [JOB]eminentSurgery was not a prestigious part of the medical profession in this period because it was such a hands-on, often bloody business. Surgeons were responsible for pulling teeth, amputating limbs, lancing boils, letting blood from patients, and also (because it was another procedure that involved using sharp instruments to cut away part of the body) cutting hair, which is why the profession was organized under the aegis of the guild of Barber-Surgeons. Doctors of "physic," who diagnosed diseases and dispensed medicine (and from which our modern term "physicians" derives) tended to look down upon surgeons. There is a sense in which the term "eminent surgeon" is a contradiction in terms: surgeons were by definition not particularly eminent. - [JOB]apprenticeshipA typical apprenticeship in this period would have lasted at least seven years. It would thus likely have been deeply embarrassing to Gulliver and his family for him to have failed to complete this apprenticeship. The reasons why Gulliver abandoned his apprenticeship are never explained, although as the following clause suggests, Gulliver may not have been all that interested in surgery, spending more time on other subjects. - [JOB]poundsForty pounds would be worth about 5,600 pounds today or $8,000. It is always hard to compare the cost of living in an era so far removed from our own, but contemporary readers would have recognized that Gulliver's family is giving him pretty minimal support, just enough to keep him going. - [JOB]LeydenThe University of Leyden (now more frequently spelled Leiden) was a well-known and prestigious school for studying medicine, and was a much better option at the time than any school in the British Isles.physic"Physic" was the period's term for what we would now call internal medicine; it is where we get the term "physician" from. Physic was a more prestigious branch of the medical profession than surgery; physicians thought of themselves as members of a profession, and looked down on surgeons--who worked with their hands--as being more working class, just another kind of manual laborer. But as with his apprenticeship to the surgeon James Bates, Gulliver did not complete his program of study in this profession, which would have lasted at least three years. And again Gulliver gives no explanation for his early departure. But any contemporary reader who knew anything about the training of people in medical fields would have noticed there is something amiss here. - [JOB]Levant The Levant is composed of the countries on the Eastern Mediterranean Sea spanning from approximately Greece to Egypt. Source: Oxford English DictionaryJuryThe Old Jury, or the Old Jewry, is a street in the City of London, the main financial and commercial district in England. It was not a fashionable residential area. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryhosier A hosier is a maker of women's panty hose, stockings, or tights. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryportion Portion refers to the dowry that Gulliver received from his wife's family at the time of his marriage. Four hundred pounds would have been a modest dowry by the standards of the period.BatesAfter having teased the reader by presenting the name of Gulliver's master in a number of different combinations, Swift finally comes out and makes the joke that we have been waiting for: "master Bates." Gulliver does not seem aware that he is making a joke about masturbation. We can be certain, however, that Swift knows exactly what he is doing. The precise point of the joke is, as often in this book, not easy to figure out, opening up a number of possibilities but not securely picking any one of them. How are we supposed to understand this bawdy joke? Masturbation, or, as it was called at the time "onanism," was written about in a number of pamphlets and books in this period, most famously in a book called Onania: or, the Heinous Sin of Self-Pollution, and All its Frightful Consequences, in Both Sexes, Considered, published sometime in the early part of the century and reproduced dozens of times over the course of the eighteenth century. Many readers of the period would have come across a copy of this book at some point. Source: Title Page of fourt edition, Google Books Masturbation was

widely condemned as a sin that was both anti-social and also dangerous,

likely to damage one's health. And it was also seen as an unhealthy

indulgence of fantasy at the expense of reality. Which suggests that one

possibility for the book that follows is that it is also a fantasy, a

kind of day-dream of Gulliver's, a man who does not seem to enjoy a lot

of success in the real world here making up a far more interesting life

for himself than he had ever really led. Swift never gives us enough

information to decide this question one way or another, but the joke,

and the fact that Gulliver seems oblivious to it, is one of many details

in the book that should lead a careful reader to be a little dubious

about the narrator's veracity. - [JOB]voyagesGulliver does not say so, but it

seems very likely that at least some of these voyages would have been on

ships transporting enslaved people to work on plantations in the

Caribbean and South America.East-Indies In this period, the "East

Indies" referred to the Indian subucontinent and also regions such as

the island archpeligo now known as Indonesia.West-Indies The islands in the

Caribbean.account To "turn to account" is turn

something into your advantage. That is to say that Gulliver is not

making any money trying to treat sailors. Which is a little strange,

because Wapping in this period was located right in the heart of

London's docklands, and would have been teeming with sailors. It is hard

not to suspect that Gulliver does not have a great reputation as a

doctor among his potential clientele. - [JOB]South-SeaThe "South-Sea" in this period could refer either

to the southern Atlantic Ocean or the southern Pacific Ocean. It is

notable that Gulliver does not want to "trouble the reader" with the

details of the voyage, except to note that it was "very prosperous" at

first. One possibility, perhaps hinted at by the fact that the ship left

from Bristol, was that the first part of the voyage involved kidnapping

people into slavery in west Africa and then selling them in the

Americas; Bristol was at this time a prominent port for departing ships

in the Atlantic slave trade. - [JOB]Van_Diemen Van Diemen's Land was the Dutch name used for what

is now the Australian island of Tasmania.cable A cable's length is a

nautical measurement that is roughly 608 feet. So the rock was spied

approximately 304 feet off the ship. Source: Oxford

English DictionaryleagueA league is about three nautical miles,

so three leagues would be about nine nautical miles.declivityA declivity is a descending

incline. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryjerkin A yellow or beige

vest or short jacket, typically made of leather, which would explain why

it can resist the arrows.page A page is a servant, often young. Source: Oxford English Dictionarytrain A train is the bottom of a robe, dress, or coat. If a

train is long enough it will drag on the ground, and thus a monarch's

train would be carried by servants. Source: Oxford

English Dictionaryforbear Forbear means "to bear, endure, or

submit to." Source: Oxford English

Dictionarylark A lark is a type of small brown bird, often known as a

songbird. Source: Oxford English

Dictionarybullet The

diameter of a musket ball was half an inch on average.hogsheads A hogshead

is a cask or barrel. Source: Oxford English

Dictionarydraught Draught is the

"drawing of liquid into the mouth or down the throat; an act of

drinking, a drink; the quantity of drink swallowed at one 'pull.'"

Source: Oxford English Dictionaryprodigious Prodigious is an adjective

meaning amazing, or extraordinary. Source: Oxford

English Dictionaryretinue

The king's retinue is a group of his attendants or closest servants.

Source: Oxford English Dictionarydisapprobation Disapprobation is "the

act of disapproving." Source: Oxford English

Dictionarysmart A smart is the feeling

of sharp pain inflicted by some outside source. Source: Oxford English Dictionarymake_water To "make water" is to urinate.

Source: Oxford English DictionarydaubedTo cover or put on. In this context the Lilliputions

are putting on the ointment. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryvictualsFood, thus

they're providing Gulliver with food and drink.packthread Small

twine or thread used to sew or close up bags. Source: Oxford English Dictionarygirt bound or secured sopiferousTo cause someone to fall

asleep. The medicine will cause Gulliver to fall sleep or pass out.

Source: Oxford English Dictionarymurder Swift is probably referring to the execution of

Charles I by Parliament in 1649, at the end of the English Civil War. It

took place on Whitehall, in front of the Banqueting House, designed by

Inigo Jones for Charles's father, James I, and still a landmark that can

be visited in London. For conservatives like Swift, the execution of a

monarch was indeed "unnatural"; even now, the execution of the head of

state is shocking to imagine.

Source: Title Page of fourt edition, Google Books Masturbation was

widely condemned as a sin that was both anti-social and also dangerous,

likely to damage one's health. And it was also seen as an unhealthy

indulgence of fantasy at the expense of reality. Which suggests that one

possibility for the book that follows is that it is also a fantasy, a

kind of day-dream of Gulliver's, a man who does not seem to enjoy a lot

of success in the real world here making up a far more interesting life

for himself than he had ever really led. Swift never gives us enough

information to decide this question one way or another, but the joke,

and the fact that Gulliver seems oblivious to it, is one of many details

in the book that should lead a careful reader to be a little dubious

about the narrator's veracity. - [JOB]voyagesGulliver does not say so, but it

seems very likely that at least some of these voyages would have been on

ships transporting enslaved people to work on plantations in the

Caribbean and South America.East-Indies In this period, the "East

Indies" referred to the Indian subucontinent and also regions such as

the island archpeligo now known as Indonesia.West-Indies The islands in the

Caribbean.account To "turn to account" is turn

something into your advantage. That is to say that Gulliver is not

making any money trying to treat sailors. Which is a little strange,

because Wapping in this period was located right in the heart of

London's docklands, and would have been teeming with sailors. It is hard

not to suspect that Gulliver does not have a great reputation as a

doctor among his potential clientele. - [JOB]South-SeaThe "South-Sea" in this period could refer either

to the southern Atlantic Ocean or the southern Pacific Ocean. It is

notable that Gulliver does not want to "trouble the reader" with the

details of the voyage, except to note that it was "very prosperous" at

first. One possibility, perhaps hinted at by the fact that the ship left

from Bristol, was that the first part of the voyage involved kidnapping

people into slavery in west Africa and then selling them in the

Americas; Bristol was at this time a prominent port for departing ships

in the Atlantic slave trade. - [JOB]Van_Diemen Van Diemen's Land was the Dutch name used for what

is now the Australian island of Tasmania.cable A cable's length is a

nautical measurement that is roughly 608 feet. So the rock was spied

approximately 304 feet off the ship. Source: Oxford

English DictionaryleagueA league is about three nautical miles,

so three leagues would be about nine nautical miles.declivityA declivity is a descending

incline. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryjerkin A yellow or beige

vest or short jacket, typically made of leather, which would explain why

it can resist the arrows.page A page is a servant, often young. Source: Oxford English Dictionarytrain A train is the bottom of a robe, dress, or coat. If a

train is long enough it will drag on the ground, and thus a monarch's

train would be carried by servants. Source: Oxford

English Dictionaryforbear Forbear means "to bear, endure, or

submit to." Source: Oxford English

Dictionarylark A lark is a type of small brown bird, often known as a

songbird. Source: Oxford English

Dictionarybullet The

diameter of a musket ball was half an inch on average.hogsheads A hogshead

is a cask or barrel. Source: Oxford English

Dictionarydraught Draught is the

"drawing of liquid into the mouth or down the throat; an act of

drinking, a drink; the quantity of drink swallowed at one 'pull.'"

Source: Oxford English Dictionaryprodigious Prodigious is an adjective

meaning amazing, or extraordinary. Source: Oxford

English Dictionaryretinue

The king's retinue is a group of his attendants or closest servants.

Source: Oxford English Dictionarydisapprobation Disapprobation is "the

act of disapproving." Source: Oxford English

Dictionarysmart A smart is the feeling

of sharp pain inflicted by some outside source. Source: Oxford English Dictionarymake_water To "make water" is to urinate.

Source: Oxford English DictionarydaubedTo cover or put on. In this context the Lilliputions

are putting on the ointment. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryvictualsFood, thus

they're providing Gulliver with food and drink.packthread Small

twine or thread used to sew or close up bags. Source: Oxford English Dictionarygirt bound or secured sopiferousTo cause someone to fall

asleep. The medicine will cause Gulliver to fall sleep or pass out.

Source: Oxford English Dictionarymurder Swift is probably referring to the execution of

Charles I by Parliament in 1649, at the end of the English Civil War. It

took place on Whitehall, in front of the Banqueting House, designed by

Inigo Jones for Charles's father, James I, and still a landmark that can

be visited in London. For conservatives like Swift, the execution of a

monarch was indeed "unnatural"; even now, the execution of the head of

state is shocking to imagine.  Source: A contemporary engraving by an unknown artist of the execution of Charles I. Note the blood spurting from the decapitated body and the executioner holding the head of the dead King up for the crowd to see. Source: National Portrait Gallery, London

- [JOB]fourscoreFourscore is four times twenty or

eighty. 80+11=91: there were ninety-one chains. Source: Oxford English DictionaryAudio2

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie Driverstang A stang is an archiac measurement of

land that was about a quarter of an acre.expedient An expedient is something done

so that one can quickly achieve something. Source: Oxford English Dictionarymaligners People who have attacked him in

public. What's strange about this, of course, is that Gulliver is a

fictional person, so no such maligners could have existed prior to the

publication of the book. alighted Got down off his horse. - [UVAStudStaff]nose

Source: A contemporary engraving by an unknown artist of the execution of Charles I. Note the blood spurting from the decapitated body and the executioner holding the head of the dead King up for the crowd to see. Source: National Portrait Gallery, London

- [JOB]fourscoreFourscore is four times twenty or

eighty. 80+11=91: there were ninety-one chains. Source: Oxford English DictionaryAudio2

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie Driverstang A stang is an archiac measurement of

land that was about a quarter of an acre.expedient An expedient is something done

so that one can quickly achieve something. Source: Oxford English Dictionarymaligners People who have attacked him in

public. What's strange about this, of course, is that Gulliver is a

fictional person, so no such maligners could have existed prior to the

publication of the book. alighted Got down off his horse. - [UVAStudStaff]nose Source: Portrait of William III, after Willem Wissing (c.1685), National Portrait Gallery, LondonThe Lilliputian

King's facial features would have reminded Swift's readers of those of

William III (1650-1702). An "Austrian lip," a thick lower lip and jaw,

was common among members of the Hapsburg family, the dynasty that ruled

the Holy Roman Empire and whose members were found in royal families

throughout continental Europe in this era. William's jaw and arched nose

are clearly depicted in this portrait from the 1680s, believed to be a

copy of a now-lost original painting by Willem Wissing. - [UVAStudStaff]deportmentDeportment is the manner with which

one conducts oneself. Source: Oxford English

Dictionary - [UVAStudStaff]prime This may be a dig

at George I, who was King of England at the time of the publication of

Swift's book, and was 66 years old. - [UVAStudStaff]sevenAnother way of associating the

Lillipution King with George I of England, who had also reigned for

seven years at the time of the publication of Gulliver's Travels. - [UVAStudStaff]felicity Felicity is the quality or state of being happy.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryscabbardA sheath for a sword. Source: Oxford English DictionaryDutch"High" Dutch (an English corruption of the German word

"Deutsch") refers to the dialect spoken by people in what is now

southern Germany, and is the ancestor of modern German. "Low" Dutch

refers to the language spoken in what is now northern Germany and the

Netherlands.Lingua A mix of the southern Romance

languages. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryBeeves Oxen or cattle.

Source: Oxford English Dictionarydemesnes Land held by

the state, or, in this case, by the monarch himself. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryfobs A small

pocket, usually for watches, money, or small valuables. Source: Oxford English DictionaryImprimisLegal

term denoting a list of items. Placed at the top of many legal documents

of the time, from wills to inventories. Source: perspectiveTelescope or spyglass. Source: Oxford English DictionaryAudio3

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverRope-dancers Rope dancers did acrobatics while suspended on a

slack line of rope above the ground; it resembled tightrope walking, but

there was much less tension in the rope.Flimnap_ Flimnap" is a near-anagram for "Walpole," and readers would have

recognized that Swift was satirizing Sir Robert Walpole, the First Lord

of the Treasury, and at this point the most powerful figure in the

British government. Swift and many others accused Walpole (with good

reason) of corruption. summerset Somersault. Souce: Oxford English

DictionaryReldresal It's not exactly clear who Swift

might be referring to here; a contemporary book purporting to identify

some of the satiric targets in the book suggests that this refers to

"T---d," which would probably be Lord Townshend, who was at this time

one of Walpole's main allies in the government. See A

Key, Being Observations and Explanatory Notes, Upon the Travels of

Lemuel Gulliver. By Signor Corolini, a noble Venetian now residing

in London. In a letter to Dean Swift. Translated from the Italian

Original (London: Edmund Curll, 1726), but it is impossible to

be sure. This book was not, of course, written by an Italian

author--there is no Signor Coroloni--but the fact that the publisher

pretended that this was the case, and also veiled the name of the person

it is trying to identify with so many dashes, indicates just how risky

it was to satirize such important figures in the government at this

time. The publisher of the Key, Edmund Curll, was

forced to stand in the pillory for seditious libel in 1728 for

publishing another book suspected to be directed at the

government.cushionsThis is probably a reference to the

Duchess of Kendal, who was known to be the mistress of George I, and who

was believed to have intervened on Walpole's behalf.threadsThe silken

threads are the same colors as the Order of the Garter, Order of Bath,

and Order of the Thistle. These were military and civilian order

conferred theoretically based on merit, but in many cases in this period

simply went to political cronies of the ruling party. Swift was

satirizing the focus on what he saw as arbitrary and possibly corrupt

distinctions and awards. In the first edition in 1726, Swift's publisher

changed the colors to purple, yellow, and white to avoid possible

political retribution. Swift was upset and wrote a note decrying this

change, and later editions restored the original colors. discovered Revealed. Souce: Oxford English Dictionaryin-a-breast Abreast. Source: Oxford English

DictionarySkyresh Believed to be a reference to the Second Earl of

Nottingham. Source: F. P. Lock, The Politics of

Gulliver's Travels (Clarendon Press, 1980), 114.Center That is, the center of the

earth.ninety-firstGiven that there is a full moon every twenty nine

days, "the ninety-first moon of our reign" is a little over seven years.

prostratingThe act of prostration is similar to kneeling or

bowing, and is meant to show submission to a higher power. Source: Oxford English Dictionary

censureA formal disapproval, criticism, or judgement. Source: Oxford English DictionaryquadrantA tool for measuring angle. A quadrant is

particularly useful for measuring angles of celestial objects, and thus

in this period was widely used for navigation, which relied on mariners

being able to triangulate their position against the movement of the

sun, the moon, and stars in the sky. This image from 1564 shows the

ancient astronomer Ptolemy, the purported inventor of the quadrant,

using one to observe the heavens.

Source: Portrait of William III, after Willem Wissing (c.1685), National Portrait Gallery, LondonThe Lilliputian

King's facial features would have reminded Swift's readers of those of

William III (1650-1702). An "Austrian lip," a thick lower lip and jaw,

was common among members of the Hapsburg family, the dynasty that ruled

the Holy Roman Empire and whose members were found in royal families

throughout continental Europe in this era. William's jaw and arched nose

are clearly depicted in this portrait from the 1680s, believed to be a

copy of a now-lost original painting by Willem Wissing. - [UVAStudStaff]deportmentDeportment is the manner with which

one conducts oneself. Source: Oxford English

Dictionary - [UVAStudStaff]prime This may be a dig

at George I, who was King of England at the time of the publication of

Swift's book, and was 66 years old. - [UVAStudStaff]sevenAnother way of associating the

Lillipution King with George I of England, who had also reigned for

seven years at the time of the publication of Gulliver's Travels. - [UVAStudStaff]felicity Felicity is the quality or state of being happy.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryscabbardA sheath for a sword. Source: Oxford English DictionaryDutch"High" Dutch (an English corruption of the German word

"Deutsch") refers to the dialect spoken by people in what is now

southern Germany, and is the ancestor of modern German. "Low" Dutch

refers to the language spoken in what is now northern Germany and the

Netherlands.Lingua A mix of the southern Romance

languages. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryBeeves Oxen or cattle.

Source: Oxford English Dictionarydemesnes Land held by

the state, or, in this case, by the monarch himself. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryfobs A small

pocket, usually for watches, money, or small valuables. Source: Oxford English DictionaryImprimisLegal

term denoting a list of items. Placed at the top of many legal documents

of the time, from wills to inventories. Source: perspectiveTelescope or spyglass. Source: Oxford English DictionaryAudio3

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverRope-dancers Rope dancers did acrobatics while suspended on a

slack line of rope above the ground; it resembled tightrope walking, but

there was much less tension in the rope.Flimnap_ Flimnap" is a near-anagram for "Walpole," and readers would have

recognized that Swift was satirizing Sir Robert Walpole, the First Lord

of the Treasury, and at this point the most powerful figure in the

British government. Swift and many others accused Walpole (with good

reason) of corruption. summerset Somersault. Souce: Oxford English

DictionaryReldresal It's not exactly clear who Swift

might be referring to here; a contemporary book purporting to identify

some of the satiric targets in the book suggests that this refers to

"T---d," which would probably be Lord Townshend, who was at this time

one of Walpole's main allies in the government. See A

Key, Being Observations and Explanatory Notes, Upon the Travels of

Lemuel Gulliver. By Signor Corolini, a noble Venetian now residing

in London. In a letter to Dean Swift. Translated from the Italian

Original (London: Edmund Curll, 1726), but it is impossible to

be sure. This book was not, of course, written by an Italian

author--there is no Signor Coroloni--but the fact that the publisher

pretended that this was the case, and also veiled the name of the person

it is trying to identify with so many dashes, indicates just how risky

it was to satirize such important figures in the government at this

time. The publisher of the Key, Edmund Curll, was

forced to stand in the pillory for seditious libel in 1728 for

publishing another book suspected to be directed at the

government.cushionsThis is probably a reference to the

Duchess of Kendal, who was known to be the mistress of George I, and who

was believed to have intervened on Walpole's behalf.threadsThe silken

threads are the same colors as the Order of the Garter, Order of Bath,

and Order of the Thistle. These were military and civilian order

conferred theoretically based on merit, but in many cases in this period

simply went to political cronies of the ruling party. Swift was

satirizing the focus on what he saw as arbitrary and possibly corrupt

distinctions and awards. In the first edition in 1726, Swift's publisher

changed the colors to purple, yellow, and white to avoid possible

political retribution. Swift was upset and wrote a note decrying this

change, and later editions restored the original colors. discovered Revealed. Souce: Oxford English Dictionaryin-a-breast Abreast. Source: Oxford English

DictionarySkyresh Believed to be a reference to the Second Earl of

Nottingham. Source: F. P. Lock, The Politics of

Gulliver's Travels (Clarendon Press, 1980), 114.Center That is, the center of the

earth.ninety-firstGiven that there is a full moon every twenty nine

days, "the ninety-first moon of our reign" is a little over seven years.

prostratingThe act of prostration is similar to kneeling or

bowing, and is meant to show submission to a higher power. Source: Oxford English Dictionary

censureA formal disapproval, criticism, or judgement. Source: Oxford English DictionaryquadrantA tool for measuring angle. A quadrant is

particularly useful for measuring angles of celestial objects, and thus

in this period was widely used for navigation, which relied on mariners

being able to triangulate their position against the movement of the

sun, the moon, and stars in the sky. This image from 1564 shows the

ancient astronomer Ptolemy, the purported inventor of the quadrant,

using one to observe the heavens. Source: Image of the Greek astronomer PtolemyAudio4

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriversidelingMoving sideways. Source: Oxford English DictionarycircumspectionCaution. Source: Oxford

English DictionarygarretGarret windows are windows in the roofs

of buildings; the highest windows in a building. Source: Oxford English DictionarycontrivanceA mechanical device or invention for a particular

situation. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryTramecksan H. D.

Kelling theorizes that Swift is making an elaborate play on words: "In

the names themselves, Swift may, by reversing foreign words, be

indicating to the reader the original difference between the two

parties, a difference not in heels but in noses. If we reverse the names

"Tramecksan" and "Slamecksan" we find that the former are "nas camard"

(nas keemart) or snub-noses while the latter are "nas camels" (nas

keemals) or camels'-noses. "Nas" is of course still a French variant for

"nez"-or may be the root of "nasus"-while "keemart" is a fairly accurate

phonetic spelling of "camard". "Kcenmals" is a phonetic spelling of

camels with "e" and "a" transposed." See H. D. Kelling, "Some

Significant Names in Gulliver's Travels," Studies in

Philology 48 (October 1951), 761-778.intestineInternal or

domestic. Source: Oxford English

DictionarymoonsA little over 476 years.six-and-thirtyNearly three years.

fomentedRoused or

instigated. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryBig-EndiansSwift

is mocking the intensity with which minor differences in religious

doctrine end up causing enormous political strife.expostulateExpress disapproval. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryAlcoranThat is, the Koran, the sacred text

in the Islamic faith.Audio5

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverplumbedMeasured the depths of. Source: Oxford English DictionaryhillockA little hill. Source: Oxford English DictionarywarwarshipspuissantFrench for powerful. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryencomiumswords or shouts of praiseside-windAn indirect means of influence.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryjuntoA faction, generally in politics. Source: Oxford English Dictionary At this time, the term

was associated with a group of Whig party politicians, who dominated the

British government through much of the early years of the eighteenth

century, so this is another moment where Swift's readers would have

recognized a parallel between Lillipution and British politics. Swift,

who identified himself more with the Tory party, was shut out of power

by dominance of the Whig Junto.diureticA substance that causes the

increased production of urine. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryAudio6

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverlarkPlucking the lark’s feather. Source: Oxford English DictionaryCascagiansswift is making up the "Cascagians" and their

writing system; there is no such nation or language. ignominiousInvolving shame or disgrace. Source: Oxford English DictionarychargesThe expenses that the defendant had incurred. Source:

Oxford English DictionaryA dishonest unprincipled man; a cunning unscrupulous

rogue; a villain. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryextenuationThat is, Gulliver is trying to diminishing the

accusation, arguing that the criminal had not so much stolen the money

as broken the trust of his master. It is not at all clear why Gulliver

would care or want to intervene in this instance.concupiscenceEager or vehement desire; the coveting of carnal

things. In short, lust. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryclemencyMildness or

gentleness of temper, as shown in the exercise of authority or power;

mercy, leniency. Source: Oxford English

Dictionaryplumb-lineA line

or cord with a weight at one end, for determining the vertical. Source:

Oxford English DictionarystaffThe white staff is a symbol of his office; in the

British government, the Lord Chamberlain has a ceremonial white,

sometimes referred to as the "wand of office" that they receive when

they are appointed, and must return to the monarch when they retire.

exchequerA royal or

national treasury. Many readers at the time would have easily associated

Flimnap with Sir Robert Walpole, the powerful Chancellor of the

Exchequer, who dominated the British political scene from 1721 until

1742. Source: Oxford English DictionaryspangleA small round

thin piece of glittering metal (usually brass) with a hole in the centre

to pass a thread through, used for the decoration of textile fabrics and

other materials of various sorts. Source: Oxford

English DictionaryAudio7

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie Driverreasons A purely political

ground of action on the part of a ruler or government, esp. as involving

expediency or some departure from strict justice, honesty, or open

dealing. Source: Oxford English

Dictionarymercy Swift might be alluding

to the speeches given by George I where he praised the mercy he showed

towards Jacobite rebels who had plotted to overthrow him in 1715; the

joke is that George and his government, far from showing any mercy, were

actually ruthless, executing as many of the ringleaders of the rebellion

as they could find.Audio8

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DrivertallowThe fat, adipose

tissue, of an animal. Source: Oxford English

Dictionary. Gulliver will use the fat of these cows to help

make the boat water-resistant, and also for lubricating the oars and

other parts of the boat.ancient An ensign, standard, or flag. Source: Oxford English Dictionarycharacter That is,

he testified to Gulliver's reliability and general uprightness. To give

someone a good "character" was to in effect to serve as a character

reference. Downs The part of the sea within the Goodwin Sands, off the

east coast of Kent, a famous rendezvous for ships. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryparish In this period, most of what we would now call the

social safety net, was governed by a 1601 statute that was known as the

Poor Law (formally 43 Eliz. I Cap. 2). Under the terms of the Poor Law,

relief in the form of food aid or money for people who had fallen into

abject poverty was handled by the Church of English at the level of

individual parishes. The relief was notoriously stingy and also

inconsistent; turning to the parish for aid was a desperate

measure.towardly Promising,

‘hopeful’, forward; apt to learn, docile: chiefly of young persons or

their dispositions. Source: Oxford English

Dictionary

Surat Surat is a city in the

modern Indian state of Gujarat, on the west coast of India. The British

East India Company established a trading post there in 1612, after which

it became a major trading port for the export of Indian textiles and

other valuable commodities.

Source: Image of the Greek astronomer PtolemyAudio4

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriversidelingMoving sideways. Source: Oxford English DictionarycircumspectionCaution. Source: Oxford

English DictionarygarretGarret windows are windows in the roofs

of buildings; the highest windows in a building. Source: Oxford English DictionarycontrivanceA mechanical device or invention for a particular

situation. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryTramecksan H. D.

Kelling theorizes that Swift is making an elaborate play on words: "In

the names themselves, Swift may, by reversing foreign words, be

indicating to the reader the original difference between the two

parties, a difference not in heels but in noses. If we reverse the names

"Tramecksan" and "Slamecksan" we find that the former are "nas camard"

(nas keemart) or snub-noses while the latter are "nas camels" (nas

keemals) or camels'-noses. "Nas" is of course still a French variant for

"nez"-or may be the root of "nasus"-while "keemart" is a fairly accurate

phonetic spelling of "camard". "Kcenmals" is a phonetic spelling of

camels with "e" and "a" transposed." See H. D. Kelling, "Some

Significant Names in Gulliver's Travels," Studies in

Philology 48 (October 1951), 761-778.intestineInternal or

domestic. Source: Oxford English

DictionarymoonsA little over 476 years.six-and-thirtyNearly three years.

fomentedRoused or

instigated. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryBig-EndiansSwift

is mocking the intensity with which minor differences in religious

doctrine end up causing enormous political strife.expostulateExpress disapproval. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryAlcoranThat is, the Koran, the sacred text

in the Islamic faith.Audio5

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverplumbedMeasured the depths of. Source: Oxford English DictionaryhillockA little hill. Source: Oxford English DictionarywarwarshipspuissantFrench for powerful. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryencomiumswords or shouts of praiseside-windAn indirect means of influence.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryjuntoA faction, generally in politics. Source: Oxford English Dictionary At this time, the term

was associated with a group of Whig party politicians, who dominated the

British government through much of the early years of the eighteenth

century, so this is another moment where Swift's readers would have

recognized a parallel between Lillipution and British politics. Swift,

who identified himself more with the Tory party, was shut out of power

by dominance of the Whig Junto.diureticA substance that causes the

increased production of urine. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryAudio6

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverlarkPlucking the lark’s feather. Source: Oxford English DictionaryCascagiansswift is making up the "Cascagians" and their

writing system; there is no such nation or language. ignominiousInvolving shame or disgrace. Source: Oxford English DictionarychargesThe expenses that the defendant had incurred. Source:

Oxford English DictionaryA dishonest unprincipled man; a cunning unscrupulous

rogue; a villain. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryextenuationThat is, Gulliver is trying to diminishing the

accusation, arguing that the criminal had not so much stolen the money

as broken the trust of his master. It is not at all clear why Gulliver

would care or want to intervene in this instance.concupiscenceEager or vehement desire; the coveting of carnal

things. In short, lust. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryclemencyMildness or

gentleness of temper, as shown in the exercise of authority or power;

mercy, leniency. Source: Oxford English

Dictionaryplumb-lineA line

or cord with a weight at one end, for determining the vertical. Source:

Oxford English DictionarystaffThe white staff is a symbol of his office; in the

British government, the Lord Chamberlain has a ceremonial white,

sometimes referred to as the "wand of office" that they receive when

they are appointed, and must return to the monarch when they retire.

exchequerA royal or

national treasury. Many readers at the time would have easily associated

Flimnap with Sir Robert Walpole, the powerful Chancellor of the

Exchequer, who dominated the British political scene from 1721 until

1742. Source: Oxford English DictionaryspangleA small round

thin piece of glittering metal (usually brass) with a hole in the centre

to pass a thread through, used for the decoration of textile fabrics and

other materials of various sorts. Source: Oxford

English DictionaryAudio7

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie Driverreasons A purely political

ground of action on the part of a ruler or government, esp. as involving

expediency or some departure from strict justice, honesty, or open

dealing. Source: Oxford English

Dictionarymercy Swift might be alluding

to the speeches given by George I where he praised the mercy he showed

towards Jacobite rebels who had plotted to overthrow him in 1715; the

joke is that George and his government, far from showing any mercy, were

actually ruthless, executing as many of the ringleaders of the rebellion

as they could find.Audio8

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DrivertallowThe fat, adipose

tissue, of an animal. Source: Oxford English

Dictionary. Gulliver will use the fat of these cows to help

make the boat water-resistant, and also for lubricating the oars and

other parts of the boat.ancient An ensign, standard, or flag. Source: Oxford English Dictionarycharacter That is,

he testified to Gulliver's reliability and general uprightness. To give

someone a good "character" was to in effect to serve as a character

reference. Downs The part of the sea within the Goodwin Sands, off the

east coast of Kent, a famous rendezvous for ships. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryparish In this period, most of what we would now call the

social safety net, was governed by a 1601 statute that was known as the

Poor Law (formally 43 Eliz. I Cap. 2). Under the terms of the Poor Law,

relief in the form of food aid or money for people who had fallen into

abject poverty was handled by the Church of English at the level of

individual parishes. The relief was notoriously stingy and also

inconsistent; turning to the parish for aid was a desperate

measure.towardly Promising,

‘hopeful’, forward; apt to learn, docile: chiefly of young persons or

their dispositions. Source: Oxford English

Dictionary

Surat Surat is a city in the

modern Indian state of Gujarat, on the west coast of India. The British

East India Company established a trading post there in 1612, after which

it became a major trading port for the export of Indian textiles and

other valuable commodities.  Source: A view of Surat in about 1690. Note the European ships in the harbor, and, to the left of the shore, a long jetty at which they can dock. From Jacob Peeters, Description des principales ville, havres et isles due golfe de Venise de cote oriental, Antwerp, 1690. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: A view of Surat in about 1690. Note the European ships in the harbor, and, to the left of the shore, a long jetty at which they can dock. From Jacob Peeters, Description des principales ville, havres et isles due golfe de Venise de cote oriental, Antwerp, 1690. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Audio9

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverCornishmanA man

from the Southwest county of Cornwall in the United Kingdom. Source: Oxford English Dictionary

agueAgue is derived from the

old French word Aguë which meant "acute fever." So ague describes

diseases such as malaria that cause high fevers. Source: Oxford English Dictionary. It is worth noting

that Gulliver, the ship's doctor, witnesses a lot of illness among the

crews whose health he is in charge of overseeing.MoluccaThe "Molucca" Islands, now generally called the Maluku

Islands, form an archipelago of more than 1000 islands in the eastern

part of modern Indonesia.

Image source: Wikimedia CommonsFindingIn this paragraph, Swift makes use of many nautical terms to the point of excess. He is most likely trying to poke fun at the travel narratives of the time which were often filled with obscure nautical terminology and jargon.longboatA longboat is one of the many boats that were carried along bigger sailing ships, such as a man-of-war ship. Longboats were manned by men with oars (usually about eight or ten men). They were used to bring sailors from the main ship to the beach, as often the main ship was too big to dock by the beach. Source: Oxford English DictionarystileA structure of steps that allows for passage over fences and hedges. Source: Oxford English DictionarygrievouslyVery severely, even painfully.supplicatingThe act of begging (often used in a religious context) that is often marked by being down on one's knees with palms facing towards the sky. Source: Oxford English DictionarylappetLapel or a flap in a garmet. Source: Oxford English DictionaryhindsLaborers or workers. Source: Oxford English Dictionarypistoles"Pistole" was a word used to refer to a number of different kinds of gold coins in this period; they would have been comparatively valuable simply because they were gold. The joke is that Gulliver is trying in effect to buy his freedom with coins so tiny as to be completely worthless in this land.trencherA trencher is a flat piece of wood or a flat piece of bread that was used as a plate during a meal. Source: Oxford English DictionarydramA dram is a unit of measurement defined as about 3.5ml of fluid, but of course in this world, a "dram cup" holds vastly more than that. Source: Oxford English DictionaryarchMischevious. Source: Oxford English DictionaryboxTo box someone's ear means to slap them on the side of the head. Source: Oxford English DictionaryChelseaA distance of about five miles.oratorySpeaking, or in the case of an infant, probably screaming. Source: Oxford English Dictionary. Gulliver is being a little sarcastic.dugNipple. Source: Oxford English DictionarydiscoursingSpeaking about. Source: Oxford English DictionarycomelyAttractive or agreeable. Source: Oxford English DictionaryhangerA short, usually curved sword. They were called "hangers" because they were hung from a belt. Source: Oxford English Dictionary Audio10

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverrequiteTo repay. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryignominyShame. Source: Oxford English DictionarypursuantIn accordance with. Source: Oxford English DictionarypillionA seat or bench behind the main driver's seat. Source

Oxford English DictionarygimletA gimlet is a hand tool for boring

holes into wood. Here, Gulliver is saying that the Brobdignagian drilled

some air holes with a gimlet, probably one like the tool depicted here.

Source: Oxford English Dictionary

Image source: Wikimedia Commons journeyA distance of about twenty miles.fopperiesFoolishness. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryvexationdistress or anxiety pumpionAn archaic word for pumpkin.scoreA "score" is 20, so they would have travelled something like 140 to 160 miles a day. This was much more than anyone could plausibly travel in the early eighteenth century, when a good day's journey on horseback or coach would be more like 30 miles.palisadoedEnclosed; fenced in. Source: Oxford English DictionarySansonNicholas Sanson was a French cartographer who created multiple atlases. These would have been large books in Europe, folio sized volumes around 19 x 12 inches; in Brobdignag, such a large book fits into a child's pocket.Audio11

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DrivermoidoresPortugese gold

coins. Source: Oxford English DictionaryguineasGold coins minted in England. A

guinea was worth a pound plus a shilling.improprietiesImproper language.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryscrutoreFrom the French "scrutoire," a desk for

writing.waitingAttendance at court. Source:Oxford

English Dictionary

evinceTo reveal or indicate. Source: Oxford English Dictionarylusus"Lusus naturae" is Latin for "freak of nature." Source:

Oxford English DictionarywindowA sash window is a

window with movable panels; these windows are still in popular use

today. Source: Oxford English Dictionary

WhigWhigs and Tories were

opposing factions in the British Parliament from the 1680's to the

1850's. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryequipage"Equipage" is literally

"equipment," but in this context it would have referred specifically

associated with the materials that went into equipping and outfitting of

horses, such as a carriage. Wealthy and powerful people would have

outfitted their horses, carriages, and the attendants who rode alongside

them with grand clothing and apparatus.colorIndignation

is defined as anger towards a misunderstanding or mistreatment. Thus,

color here refers to the flushing of Gulliver's face from anger. Source:

Oxford English DictionaryartbitressAn arbitress is the feminine

form of an arbiter, which is a person who has the ultimate decision

making power. Source: Oxford English

DictionarypratingTalking foolishly. Source: Oxford

English DictionaryglassA mirror.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryreparteesWitty remarks and conversations. Source: Oxford English DictionaryscurvyContemptible.

Source: Oxford English DictionarycashieredTo dismiss from one's position. Source: Oxford English DictionaryentreatyRequest.

Source: Oxford English Dictionaryralliedlightly mockedpiecemealPiece by piece. Source: Oxford English DictionaryAudio12

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DrivercounterpoiseOppose. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryTartary"Tartary" was the term that western Europeans in this period often used

to refer to central Asia in general, an area now composed of parts of

Ukraine, Russia, Mongolia, and China. It's far from a precise

geographical term, and does not map accurately onto any specific place.

Western Europeans like Gulliver (and Swift) simply did not know all that

much about this part of the world. WestminsterWestminster Hall is the

oldest part of the medieval palace of Westminster, the seat of

government in London. Gulliver seems to be thinking of the large stone

squares that, then and now, make up the floor of the Hall.wenA cyst, or possibly a goiter

caused by the lack of iodine in the man's diet. Source: Oxford English Dictionarywool-packBags of

wool bagged for sale. Source: Oxford English

DictionarylouseA single insect, for which the plural is "lice."

Gulliver (and Swift) may be thinking of the images of a louse under a

microscope drawn by Robert Hooke in his 1667 book Micrographia.

A louse as seen under a microsope, from Robert Hooke, Micrographia. Image source: Wikimedia CommonsrootedRooting is the action of digging with one's snout. Rooting is a common act done by pigs. Source: Oxford English Dictionary sedanA sedan-chair, a chair by which a wealthy person would have been carried by servants.liveryDress or uniform. Source: Oxford English DictionarySalisburyThe steeple at the Salisbury Cathedral is 404 feet tall. cupolaThe diameter of the cupola, or dome of St. Paul's Cathedral in London is 112 feet. shewsAn older spelling for shows. Source: Oxford English DictionaryAudio13

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverespalierUsually referring to a fruit tree that has been

trained to grow up against a wall or a solid frame.cudgelA stick used for beating, similar to a club. Source:

Oxford English DictionarylinnetA

type of finch.scrupleHesitate. Source:

Oxford English DictionarymalefactorA

criminal. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryVersailles"Jet d'eau" is French for water

jet or fountain. At the Palace of Versailles there are many fountains

that contain water jets. wherryA rowboat for

carrying passengers. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryjoinerA craftsman of wood who could make furniture or the

wooden parts of a building, such as stairs and window frames. Audio14

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverleveeA morning meeting held

where visitors come to see the King as he wakes up and goes about his

morning. Source: Oxford English DictionaryawlA pointed tool

for making holes. Oxford English

DictionaryspinetA

small keyboard instrument, usually a small harpsichord, but sometimes a

piano. sagacitywisdomsignalsignificant or

importantDemosthenesDemosthenes (384-322 BCE) was a Greek politician who was famous for his

orations.CiceroCicero (106-43 BCE)

was a famous Roman orator and politician.felicityHappiness.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryPeersThe House of Peers, also known as the

House of Lords, is the upper house in the Parliament of the United

Kingdom. In this era, the House of Lords was entirely composed of

noblemen who had gained their seats through inheritance, as well as

bishops in the church of England. In this passage, while Gulliver is

loyally touting the excellence of the British political system, Swift is

being deeply ironic and satirical, because any reader would have

recognized that the government described here bore little resemblence to

the frequently corrupt government of the period. patrimoniesInheritance (generally of a church or religious

body). Source: Oxford English DictionaryjudicatureIn this

era, the House of Lords functioned in effect as the highest court in

Britain, the final court of appeal.bulwarkStrong "defense or safeguard."

Source: Oxford English DictionaryCommonsThe lower house of Parliament, whose

membership was, in theory, by election. But many members of the House of

Commons were put there by local noblemen, and elections were frequently

very corrupt.culledGathered or plucked. Source: Oxford

English DictionarymemorandumsNotes

to aid memory. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryavariceGreed. Source: Oxford English

DictionarypartialitiesBiases. Source: Oxford English

DictionarychaplainsMembers of the clergy who were

employed privately by a noble family as their personal religious

advisor.servilelyWith the spirit of a slave or a

servant. Source: Oxford English DictionarychanceryThe court of the Lord Chancellor in England, which

typically handled property disputes, and was notorious for expensive,

drawn-out procedures.penningAuthoring; writing up.pecuniaryfinancialcordialsComforting,

usually sweet alcoholic drinks, such as a liqueur. habituateTo get used to; to grow

accustomed.perfidiousness_Deceitfulness or unfaithfulness. Source: Oxford English Dictionaryn0128To

bring together in a concise manner to repeat or summarize. Source: Oxford English DictionarypanegyricA speech of praise.perniciousHarmful

or villainous. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryodioushatefulAudio15

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverlaudablePraiseworthy. Source: Oxford English DictionaryHalicarnassensisDionysius of

Harlicarnassus (60-c 7 BCE) was a Greek historian who was best known for

a history of Rome. Oxford English

Dictionaryingratiateto curry

favorcontriverInventor. Source: Oxford English

DictionarylenityMildness [or]

gentleness; leniency. Source: Oxford English

DictionarydeterminationCessation or end to a judicial case. Source: Oxford English Dictionary.transcendentalsMental conceptions; ideas or abstractions that

are not about the physical world.mercurialQuick-witted or imaginative. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryleafPage. Source: Oxford English

DictionarypasteboardPasteboard is about as thick as card stock or

cardboard. Source: Wikipediafoliosfolio was the largest book size available in Swift's

day.floridFlowery or ornamental. Soruce: Oxford English

DictionaryinclemenciesSevere weather. Source: Oxford English

DictionarygentryA rank below the

nobility but above the common people.Audio16

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DrivertumbrilA cart. Source: Oxford English

DictionarypropogateTo increase or multiply, such as by reproduction.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryquarrypreybuffetsHits or blows.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryNiagaraThat is, louder than the roar of Niagara

Falls.disconsolateGloomy or despondent. Source: Oxford English

DictionarypigmiesPeople of small stature. Source: Oxford English Dictionarysunksunk immediatelybiscuitHardtack or a simple biscuit/cracker that was made on ships made from

flour, water, and occasionally salt. Because of its inexpensiveness and

non-perishable qualty it was often taken on ships. imputedAttributed to or ascribed to. Source: Oxford English DictionaryleagueA league is about three miles, so thus

a hundred leagues would be about three hundred miles. Source: Oxford English Dictionarytinctureextract or

componentcandorIntegrity, honesty. Source: Oxford English DictionaryveracityTruthfulness. Source: Oxford English DictionarypippinA variety of apple

first cultivated in Kent, in southern England.three-pence_A

silver three-pence coin has a diameter of 16.20mm.PhaetonIn Greek mythology, the son of

Helios, the sun god. Phaeton rode his father's chariot (which in myth

carried the sun through the sky during teh day), but lost control of the

horses and plunged into the sea.TonquinModern-day

Vietnam.New_Holland_That is,

Australia; the first Europeans to map Australia were Dutch, and though

they never established a colony there, much of what we now call

Australia was referred to as New Holland by Europeans until the early

nineteenth century. farthingA quarter of a penny; that is, a

coin with very low value.Audio17

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverdefrayTo pay, especially in the sense of

offset. Source: Oxford English DictionarysloopA small

boat. Source: Oxford English DictionarytrafficTo trade. Source: Oxford English DictionarypinionedBeing bound or

shackled. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryreprobateA malicious

person. Source: Oxford English DictionaryheathBits of shrubs and

twigs. Source: Oxford English DictionaryvergeEdge or border.disquietudesDisturbances. Source: Oxford English DictionaryAudio18

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DrivertactionTouching or contact. Source: Oxford English

DictionarycogitationThinking

or reflection. Source: Oxford English

DictionarykennelA street drain or a gutter. Source: Oxford English DictionaryconcourseA crowd or

gathering of people. Source: Oxford English

DictionarytrussedTied. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryhautboysA woodwind

instument of a higher pitch than the bassoon. It is the ancestor of the

modern oboe, which is a corruption of "hautboy," itself a corruption of

the French for "high wood." Source: Oxford English

DictionaryetymologyThe etymology of Laputa is fairly obvious; the word

is derived from the Spanish "la puta" or prostitute. Gulliver is thus

either very dumb, or is playing dumb. Readers have associated the name

with the idea that the Laputans have corrupted their power of reason. obtrudeTo force unto

someone. Source: Oxford English

Dictionaryleague Approximately 310 miles. Source: Oxford English DictionaryvoyageAt about 310 miles

in 4.5 days (108 hours,) Laputa is moving at about 2.87 miles per hour.

(Perhaps the actual speed of Laputa is a bit more, however, it's

impossible to calcuate the floating island's wind resistance, so 2.87 is

a good approximation).spheres"One or other of

the concentric, transparent, hollow globes imagined by the older

astronomers as revolving round the earth and respectively carrying with

them the several heavenly bodies (moon, sun, planets, and fixed stars)."

Source: Oxford English Dictionary. Oddly enough,

for the great thinkers that they are, the Laputians are still following

the geocentric model of the solar system.bevelBevel is

the action of cutting away at something so as to change the angle from

90 degrees to something more acute or obtuse. Source: Oxford English DictionaryinfirmityLack of strength or power.

Source: Oxford English DictionaryeffluviaAn

imperceptible stream of flowing particles. Source: Oxford English DictionaryperihelionThe

point in a planet's revolution when it is nearest the sun. Source: Oxford English DictionarycapricesFancies or whimsies. Source: Oxford English DictionaryAudio19

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriveradamantA hard rock or mineral. Source: Oxford English DictionaryloadstoneA magnetic

oxide of iron. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryshuttleA box containing thread that is

thrown back and forth across a loom to weave cloth.obliqueNeither horizontal or vertical, but rather at some slanted angle

between the two. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryperiodsThe length of oen revolution. Source: Oxford English DictionarydearthA time of scarcity, specifically in

terms of food or other necessary resources. Source: Oxford English DictionarydemesnPossession. Source: Oxford English DictionaryexorbitancesOutragious demandsAudio20

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie Driverpounds_EnglishA substantial sum,

enough to live on comfortably for a year or more in Britain at this

time.grandeeA high-ranking

nobleman.MunodiThe name Munodi is

probably designed to echo the Latin phrase "mundum odi," or "I hate the

world." Here, Munodi has withdrawn himself from Laputan society, for

which he clearly has contempt.AcademyAs

imagined in this part of the book, The Academy of Projectors in Lagado

is a satire on the Royal Society, the world's first organization devoted

to natural science, founded in London in 1660. The Royal Society is now

remembered for its innovative sponsorship of experimental science, and

some of the expriments mocked here are not all that far removed from

experiments described in the Society's journal, the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, a

journal that is published to this day. Like many conservative thinkers

of this era, Swift sees the Royal Society and experimental science as a

kind of fad, its members wasting their time pursueing trivial

things.projectorSomeone who

came up with projects designed to advance the cause of science and

improve society. By this time, the term "projector" was also sometimes

used perjoratively to describe people who engaged in fraudulent

activities like business scams. Audio21

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverhermeticallySealed so tightly that no contaminant can enter.rawCold and damp. Source: Oxford English DictionarytinctureColour, dye,

or pigment. Source: Oxford English

DictionarygallGall

bladder. Source: Oxford English

DictionarycalcineTo heat for the

purpose of breaking down the item. Soruce: Oxford

English DictionarymastThe fruit of various nut bearing trees. Source: Oxford English DictionaryweathercockA type of weather vane where

the vane is a rooster that turns with the direction of the wind. Source:

Oxford English Dictionary

diurnalDaily or day-long. Source: Oxford English

DictionarycolicAbdominal pain such as

to the stomach, colon, or bowels. Source: Oxford

English DictionarybellowsA bellows is an instrument that blows

air into a fire. Source: Oxford English

Dictionary

lank"Loose from emptiness." Source: Oxford

English DictionarynitrePottasium nitrate.percolateTo filter

or sift a liquid. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryfounderingBreaking. Source: Oxford English DictionarychaffThe husks of corn or other grain plants. Source: Oxford English Dictionary. That is, the projector

wants to try to grow grain by using the husk rather than the seeds,

which is, of course, impossible.seminalThat is, the husks, the projector

believes, are where the real power of germination lies.superficiesThe surface layer. Source: Oxford English DictionarydelineateTo draw, portray, or write down.

Source: Oxford English DictionarycephalicReferring to the head. Source: Oxford English Dictionary. It's not exactly clear

how a tincture or extract could be made out of a head.bolusA very large pill.Audio22

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverchimerasFrom Greek mythology, a fantastical

beast that is made up of various different parts of different animals.

Source: Oxford English DictionarylicentiousnessLawlessness. Source: Oxford

English Dictionaryebullientagitated Source: Oxford English DictionarypeccantDiseased. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryscrofulousScrofula is a disease that causes the lymph nodes

and glands to swell and deteriorate, especially around the neck. Source:

Oxford English DictionaryfetidBad smelling. Source: Oxford English

DictionarypurulentPus-like. Source: Oxford English DictionaryructationsBurps. Source: Oxford English Dictionarylenitives_A wide variety of different

medicines. Source: Oxford English

DictionarypertOutspoken. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryocciputThe back of the head. Source: Oxford English

DictionarycommodiusBeneficial, good. Source: Oxford English DictionaryTribniaAn anagram for

"Britain."LangdenAn anagram for "England."forfeituresThe

loss of property of money given up as the result of a court case. The

sense is that politicians are in effect stealing money by seizing money

forfeited in legal proceedings.gibbetGallows. Source: Oxford English DictionarycapA jester's cap. Source: Oxford English Dictionary

tunA cask. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryAudio23

Librivox recording, read by Lizzie DriverPortsmouthA town

on the south coast of England and a major port, with a large

dockyard.five_leaguesAbout 17 miles. Source: Oxford

English DictionarybarqueA small sailing vessel, usually with

three masts.WightThe Isle of Wight, off the south coast of England is

about 150sq miles, thus Glubbdubrib is about 50sq miles. Source:

Wikipedia.anticGross, weird, or absurd. Source: Oxford English DictionaryAlexanderAlexander the Great (356-323 BCE) was the king of the Macedonian empire

who created the largest empire of the ancient world. His influence

caused the emergence of the Hellenistic Period. he was rumored to have

died by poison. Source: WikipediaArbela_The battle of

Arbela, also known as the battle of Gaugamela, saw an outnumbered

Alexander the Great defeat the Persians. Source: WikipediaHannibalHannibal Barca (247-183) BCE, a

Cathaginian general who led one of the most famous military crusades

when he took his army across the Alps to fight the Roman Republic.

Source: WikipediavinegarAccording to the Roman historian

Livy, Hannibal had his soldiers boil vinegar and pour it over rocks to

break them up so that he could make his way through the Alps. The story

may or many not be true. Source: WikipediaCaesarJulius Caesar (100-44 BCE) A Roman

politician and general who was a member of the first triumvirate with

Crassus and Pompey. With his hunger for power he declared himself

dictator. He was assassinated by rivals on the Ides of March in 44 BCE,

leading to a long civil war that resulted in the end of the Roman

Republic and the foundation of the Roman Empire. PompeyPompey (106-48 BCE), was a ruler of the late Roman

Republic and general who was a part of the first triumvirate alongside

Caesar. However, their friendship didn't last long as they fought for

control of Rome. Losing against Caesar in the Battle of Pharsalus in 48

BCE, Pompey fled to Egypt where he was later assassinated. Source:

WikipediasenateA long enduring political body in Rome

based on a Republican government where a state is ruled by a body of

elected governing citizens. Source: WikipediaBrutusMarcus Junius Brutus, 85-42 BCE. Famed assassin of Caesar, Brutus was a

Roman politician of the Roman Republic. During the civil war between

Pompey and Caesar for power, Brutus sided with Pompey, but surrendered

to Caesar after Pompey's defeat. After assassinating Caesar with his

fellow liberators, Brutus later went on to commit suicide after being

defeated by Caesar's grandnephew Octavian. Source: Wikipedia venerationRespect. Source: Oxford English

DictionaryconsummateComplete

or perfect. Source: Oxford English

DictionarylineamentPortion. Source: Oxford English DictionaryJuniusJunius is a famous family of Rome; the

specific reference is probably to Lucius Junius Brutus, a founder of the

Roman Republic. Source: WikipediaSocrates_Socrates (470-399 BCE) Famed Greek philosopher and in

a real sense the origin point of European philosophy. While Socrates

never wrote anything himself, his method of "Socratic inquiry" conducted

through intense dialogue and his theories live through the writings of

his student Plato. Source: WikipediaEpimanandas_Epaminondas (?-362 BCE) A Greek general who free

Thebes from Spartan Control. Source: WikipediaCatoCato the Younger (95-6 BCE). A statesman of the Roman

Republic. He was a famous orator known for hatred for corruption. Cato

became a figure of admiration among eighteenth-century British political

thinkers for his integrity. Source: WikipediaMoreSir Thomas More 1478-1535 CE. A Renaissance humanist who

was famed as a lawyer, philosopher, statesman, and councilor to the

King. He opposed the Protestant Reformation. Source: WikipediasextumviriteA group of six. Source: Oxford