Headnote for Arthur Conan Doyle

By

Tonya Howe

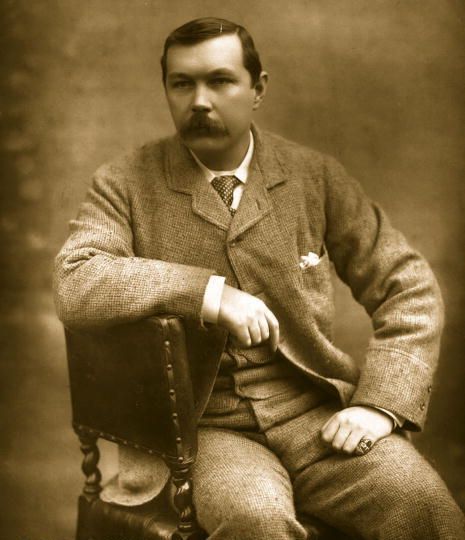

Source: Photographic portrait of Doyle (1890)Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930)

was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in May of 1859, to Irish Catholic parents; his

father was an alcoholic who experienced significant psychiatric illness throughout

his life, but Doyle was very close to his mother. For a period of their lives, the

family lived in characteristically squalid tenement housing. He was sent to live and

study in England as a child, and he eventually rejected the faith of his parents and

became agnostic. In his twenties, he studied medicine at the University of

Edinburgh, and he began writing during that period of his life with some minor

successes. After graduating, he served briefly as a ship’s surgeon traveling to West

Africa, and then set up a series of unsuccessful medical practices. After marrying

twice, first to Louisa Hawkins and after her death to Jean Leckie, he returned to

South Africa where he served as a field surgeon during the Second Boer War. Elements

in his own biography therefore connect Doyle to James Watson, the doctor and

military man. Like Watson, Doyle was also athletic; he played soccer, cricket, and

golf, among other sports, and he boxed, as well. He eventually turned to writing—as

does Watson—as a way to make his living, though he never stopped studying medicine,

which became an important part of his most famous literary creations. The image included here is a photograph of Doyle from 1890, by Herbert Rose Barraud (1845-1896), in the public domain.

Source: Photographic portrait of Doyle (1890)Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930)

was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in May of 1859, to Irish Catholic parents; his

father was an alcoholic who experienced significant psychiatric illness throughout

his life, but Doyle was very close to his mother. For a period of their lives, the

family lived in characteristically squalid tenement housing. He was sent to live and

study in England as a child, and he eventually rejected the faith of his parents and

became agnostic. In his twenties, he studied medicine at the University of

Edinburgh, and he began writing during that period of his life with some minor

successes. After graduating, he served briefly as a ship’s surgeon traveling to West

Africa, and then set up a series of unsuccessful medical practices. After marrying

twice, first to Louisa Hawkins and after her death to Jean Leckie, he returned to

South Africa where he served as a field surgeon during the Second Boer War. Elements

in his own biography therefore connect Doyle to James Watson, the doctor and

military man. Like Watson, Doyle was also athletic; he played soccer, cricket, and

golf, among other sports, and he boxed, as well. He eventually turned to writing—as

does Watson—as a way to make his living, though he never stopped studying medicine,

which became an important part of his most famous literary creations. The image included here is a photograph of Doyle from 1890, by Herbert Rose Barraud (1845-1896), in the public domain.

Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes story was A Study in Scarlet, which he wrote in three weeks and published in 1886. The Sign of Four, the second Holmes and Watson story, was published in Lippincott’s Magazine of February 1890. These stories became highly popular, though Doyle himself thought they “[took his] mind from better things” and he killed Holmes off in a 1893 story. However, the public was so upset that the character had been killed that Doyle was forced to resurrect him in 1901. Overall, Doyle wrote 60 pieces featuring the detective, who has remained an iconic figure, and the subject of much recreation in print and film—but Doyle wrote other material, as well, including theatrical pieces for the stage.

Doyle modeled Sherlock Holmes on one of his professors at the University of Edinburgh, Dr. Joseph Bell, who advocated close empirical study and deductive thinking as the chief tools in diagnostic medicine, is sometimes seen as a progenitor of modern forensic science. Among other investigative activities, Bell consulted with Scotland Yard on the notorious Jack the Ripper murders, and he also served as Queen Victoria’s private physician when she visited Scotland.

Literature in Context contains three Doyle pieces: The Speckled Band, The Copper Beeches, and The Sign of Four.

The Sign of Four (1888)It is impossible to understand The Sign of Four without considering several important contexts. Doyle wrote during the Victorian and Edwardian eras, and he died in 1930—after seeing several wars, including the First World War, reshape the modern world. The 19th century was known for its quickly growing economy, characterized by factory labor and industrialization. During the period of this novella, London was an incredibly dirty and polluted city as a result. This was a truly class-based society, with a middle class and a working class that saw themselves as such, distinct groups of people with characteristic traits and interests. But class was not just about income; it is both economic and cultural, extending to what sort of occupation and education you had, how your family was structured, political beliefs, sexuality, and even how you spent your free time—those who read the “penny dreadfuls” of the day were not in the same class as those who read Greek or Latin, or even the “classics” of British literature. Science was popularized as a form of entertainment—mesmerism, electricity, and photography were all entertainment economies that grew out of scientific developments of the 19th century, and Doyle himself was a spiritualist (he met Harry Houdini!). Literacy was rapidly growing, and print had reached truly popular proportions--magazines, circulating libraries, newspapers made both knowledge and entertainment common and accessible. Like other Holmes and Watson tales, The Sign of Four, like most of Doyle's Watson and Holmes tales, was published in periodical form, easily accessible by almost any reader. It was not, however, serialized because of its short length. In the 19th century, many novelists published “serially,” meaning their works were released piecemeal in magazines, and therefore more accessible to working and middle-class readerships.

An important element of this material context is the gender ideology of the Victorian period. While the vote was expanding and women’s suffrage was in full swing, women were seen in a paradoxical light. On the one hand, femininity was seen as central to the moral power of the middle class; and yet, women are separated fully from the masculine world of Watson and Holmes. Victorian gender roles are very much in evidence in The Sign of Four; consider that Dr. Watson’s central conflict is how to negotiate the conventions of class and gender that keep him from romantically pursuing Miss Morstan. It is often—and falsely—claimed that the Victorian era is a “sexually repressed” period; in reality, sexuality and gender were highly monitored. Pay attention to the way that Doyle reveals the subtle landscape of acceptable and unacceptable gender norms. What attitudes shape the gendered depiction of Mary Morstan? Thaddeus Sholto? Holmes? Watson?

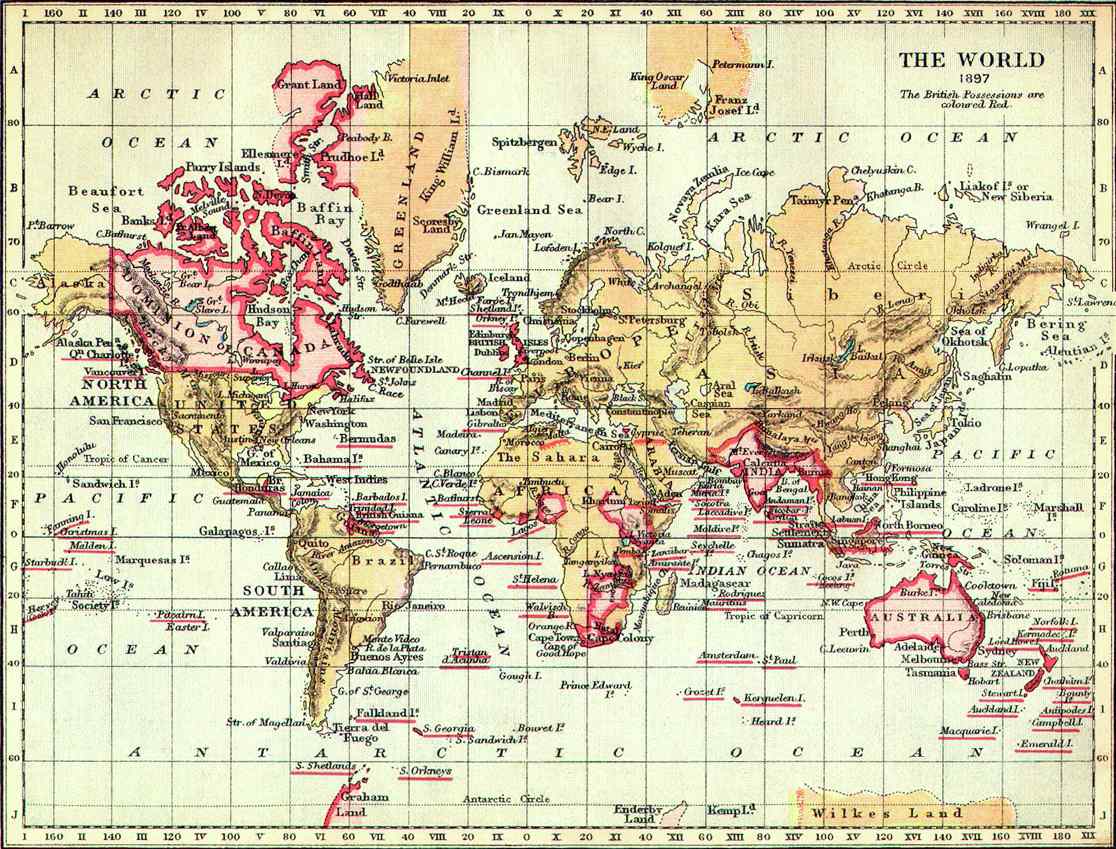

Source: 1897 map of the world, British posessions noted in redDuring the Victorian period, Britain was the most powerful empire in the world, with

territories across the globe. In the image here, an 1897 map of the world, British imperial possessions are noted in red. It was said that “the sun never sets on the British

empire,” referring both to the fact that there were British colonies all around the

world (there was always a place where the sun had not yet set), and the belief that

the empire would persist in perpetuity. Despite its immense wealth, much of that

wealth was consolidated at the top. Because of the shifting economy, there were very

high numbers of individuals in poverty—think of Holmes’ “Street Arabs.” About 75% of

the whole population of London was in poverty. Virtually none of the vast wealth of

the empire trickled down to the working classes, but it was precisely this colonial

income that grew the middle classes, increasingly seen as the “moral center” of

English society. The story of The Sign of Four is driven by

this colonial context; the mystery at the heart of the tale is a stolen treasure

that once belonged to India, while the very English Miss Mary Morstan in some ways

represents all that must be kept safe from the dangerous non-English world, and yet

is also the rightful beneficiary of the wealth of empire. As you read, pay attention

to the way that “civility” and “Englishness” are represented. To what are these

features opposed? How are “the Four” characterized? What about the Sholtos and

Captain Morstan? Tonga? If we think of The Sign of Four as an

imperial tale, what roles do Watson and Holmes play?

Source: 1897 map of the world, British posessions noted in redDuring the Victorian period, Britain was the most powerful empire in the world, with

territories across the globe. In the image here, an 1897 map of the world, British imperial possessions are noted in red. It was said that “the sun never sets on the British

empire,” referring both to the fact that there were British colonies all around the

world (there was always a place where the sun had not yet set), and the belief that

the empire would persist in perpetuity. Despite its immense wealth, much of that

wealth was consolidated at the top. Because of the shifting economy, there were very

high numbers of individuals in poverty—think of Holmes’ “Street Arabs.” About 75% of

the whole population of London was in poverty. Virtually none of the vast wealth of

the empire trickled down to the working classes, but it was precisely this colonial

income that grew the middle classes, increasingly seen as the “moral center” of

English society. The story of The Sign of Four is driven by

this colonial context; the mystery at the heart of the tale is a stolen treasure

that once belonged to India, while the very English Miss Mary Morstan in some ways

represents all that must be kept safe from the dangerous non-English world, and yet

is also the rightful beneficiary of the wealth of empire. As you read, pay attention

to the way that “civility” and “Englishness” are represented. To what are these

features opposed? How are “the Four” characterized? What about the Sholtos and

Captain Morstan? Tonga? If we think of The Sign of Four as an

imperial tale, what roles do Watson and Holmes play?

Two specific elements of England’s imperialism are essential for understanding The Sign of Four. Doyle himself served as a field surgeon in the Boer War, as Watson did in the Second Anglo-Afghan War. The Boer War (1899-1902) was fought between the British Empire and two independent Boer states over the British Empire's influence in South Africa. The “Boers” (now often termed Afrikaners) are the Dutch-speaking descendants of 17th and 18th century colonial settlers. The Boer republics were annexed by Britain to became South Africa. During this time, Britain also administered Egypt—which Doyle also visited. The Second Afghan war (1878-1880) was fought between Britain and the Afghan state because then—as today—Britain was worried about Russian influence in the region. Doyle’s personal experience in South Africa, Watson’s experience in Afghanistan, and with the vivid presentness of the global world to the Victorian English more broadly is important to keep in mind as you read.

But perhaps even more significant than the Boer war for The Sign of Four, however, is the British colonization of India, which is the direct backdrop against which the novella is set. In 1600, the East India Company was set up to facilitate trade principally between England and the Asian subcontinent. The EIC dominated trade in all the luxury goods of the time, as well as in saltpetre, a chief ingredient in gunpowder, and it had its own vast armies. From 1757 to 1858, the East India Company essentially ruled India. Indians resisted Company rule, and this resistance came to a head with the Indian Rebellion of 1857—sometimes called the Sepoy Mutiny or the First Indian War of Independence. There are many reasons for the rebellion, including British administrative practices, military authority, traditional caste systems, religious division, and more. But the tipping point came with a new munition the Company gave to its soldiers, including the Sepoys—Indian members of the Company army. The bullets were initially greased with animal fat, deeply offensive to both Hindus and Muslims. The rebellion ignited, and it would last for three years. Widespread atrocities led to hundreds of thousands of Indian deaths, and a large number of British in India were also killed. The Rebellion led to the end of Company rule and saw the creation of the “British Raj,” or was monarchial administrative rule. Queen Victoria became the Empress of India in 1877. The Sign of Four was published in 1890, but is set against the backdrop of the Indian Rebellion, and the penal colonies set up in the Andaman Islands, where “the Four” were imprisoned; Tonga is also a native Andaman. Captain Morstan and his comrades were stationed in the penal colony, and through their machinations, the treasure stolen by the Four during the Rebellion in turn made its way to England. It is the quest to discover this treasure and uncover its history that sets the plot of Doyle’s novella in motion.

Both because of Britain’s long history and its global concerns, London was a multicultural city, a modern city, a mercantile city. The Sign of Four tells a story that is beholden to those values—in addition to being a rollicking good read.