Headnote for T. S. Eliot

By

Tonya Howe

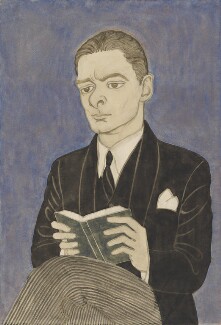

Source: Powys Evans, Portrait of T. S. Eliot (National Portrait Gallery, UK)Thomas Sterns Eliot (1888-1965) was born in

St. Louis, Missouri, to a wealthy family historically from New England; his father

was a business man, and his mother a social worker and a poet. He lived in St. Louis

for much of his youth, studying at a college preparatory school affiliated with

Washington University, before leaving for Massachusetts. He earned a BA from Harvard

in 1909, and continued on to earn a MA, both degrees in literature. Youthful

attempts at poetry failed, but during his college years he became much more

successful and he met many influential people, including the future publisher of The Waste Land. Eliot also studied philosophy at the Sorbonne

and Sanskrit, again at Harvard. It is likely that his natural tendency toward books

was enhanced by physical limitations caused by a hernia; he that he focused so much

of his energy on literature. As the first World War broke out, Eliot was heading to

Oxford on a scholarship, but he spent a lot of time in London, which was accessible

by train. There, he met the poet Ezra Pound, to whom Eliot dedicated The Waste Land. Having left his first love, Emily Hale, in

the US, he married Vivienne Haigh-Wood in 1915—though they did not have a happy

relationship and eventually separated (Vivienne died in a mental asylum, and Eliot

remarried very late in life to the 30-year old Esmé Fletcher. Eliot officially

renounced US citizenship for British citizenship in 1927.

Source: Powys Evans, Portrait of T. S. Eliot (National Portrait Gallery, UK)Thomas Sterns Eliot (1888-1965) was born in

St. Louis, Missouri, to a wealthy family historically from New England; his father

was a business man, and his mother a social worker and a poet. He lived in St. Louis

for much of his youth, studying at a college preparatory school affiliated with

Washington University, before leaving for Massachusetts. He earned a BA from Harvard

in 1909, and continued on to earn a MA, both degrees in literature. Youthful

attempts at poetry failed, but during his college years he became much more

successful and he met many influential people, including the future publisher of The Waste Land. Eliot also studied philosophy at the Sorbonne

and Sanskrit, again at Harvard. It is likely that his natural tendency toward books

was enhanced by physical limitations caused by a hernia; he that he focused so much

of his energy on literature. As the first World War broke out, Eliot was heading to

Oxford on a scholarship, but he spent a lot of time in London, which was accessible

by train. There, he met the poet Ezra Pound, to whom Eliot dedicated The Waste Land. Having left his first love, Emily Hale, in

the US, he married Vivienne Haigh-Wood in 1915—though they did not have a happy

relationship and eventually separated (Vivienne died in a mental asylum, and Eliot

remarried very late in life to the 30-year old Esmé Fletcher. Eliot officially

renounced US citizenship for British citizenship in 1927.

Eliot’s first major poetic success was "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," published in 1915 in Poetry, an important magazine then edited by Pound. Seven years later, he published The Waste Land, and after that, several other poems and plays. His playful collection of poems, Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, became the basis for the hit Broadway musical Cats. His last major work was The Four Quartets, published in four separate named parts from 1936 to 1942. It was this work that led to the Nobel Prize in Literature, which he was awarded in 1948, "for his outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry." Eliot also wrote plays and literary criticism. To learn more about Eliot, you might find Angelica Frey’s biography of interest. This headnote draws on material from this article and other commonly available web sources. Eliot was also something of an anti-semite, often expressing stereotypical beliefs about Jewish people. His friend and mentor Ezra Pound, however, was not only anti-Semitic but fascist as well, and under indictment for treason against the US, he ended up in St. Elizabeths Hospital, a federal mental institution in Southeast Washington, DC.

The Waste Land is a modernist text. Modernism is a philosophical and aesthetic movement of the early 20th century, broadly 1890-1940, which developed after and as a result of the innovations of the industrial revolution. The industrial revolution, which began in the 18th century and culminated in the middle of the 19th century, radically altered the basic nature of life in Western society and ushered in the technological era we experience today. In literary history, modernism reached its most clear articulation during the period of World War I, which seemed to epitomize the mechanized destruction of older forms of human experience. Factory production turned people into cogs in a much larger machine; new work in science saw the development of mustard gas and other forms of chemical warfare used for the first time in World War I; so too with the machine gun, the tank, the bomb, all among the new technologies of death that killed millions and demolished the landscape of much of Western Europe. The Waste Land was the work that cemented Eliot’s reputation as an important writer in the modernist movement. The title of the poem is virtually a direct allusion to the effect of shelling. Though Eliot himself dismissed this reading, it is difficult not to see his work through this lens. The panoramic photograph below, from the Imperial War Museum, shows the ruins of a farm after the Battle of the Somme in 1916, captured by Lieutenant Ernest Brooks. Modernist poets and artists rejected the aesthetic forms of the previous generations and the mode of storytelling that often accompanied them—for instance, the realism of the 19th century was rejected in favor of fragmented, daring modes of expression that tried to capture a new, broken reality. Modernist writers like James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, and Gertrude Stein channeled the questions raised by the modern world—in particular the question of whether and to what extent it is possible to tell stories or make art in this brave new world—into the very fabric of their work. Artists in many media were responding as well—in music, Claude Debussey and Igor Stravinsky were creating radically new modes of expression; in painting, Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso built on the experimentations of the Impressionists, who fractured light in pursuit of new ways of seeing. The first portrait of Eliot, above (1920), was painted by Powys Evans, also a modernist most well-known for his caricatures (National Portrait Gallery UK). To read more about the impact of the first World War on the development of modernism in literature, you might find this accessible article from The Irish Times interesting; the article touches on The Waste Land and several other key pieces of literature from the era.

Perhaps one of the most challenging and influential of texts in all of Modernist

literature, The Waste Land features multiple characters, multiple voices, and

multiple vignettes flitting in and out of visibility. Published in 1922 (first in a

London journal, then in an American one, and finally as a standalone book with

footnotes by the author), the long poem is most often examined as a response to the

shattering experience of the first World War, using the grail legend as a loosely

connective thread.

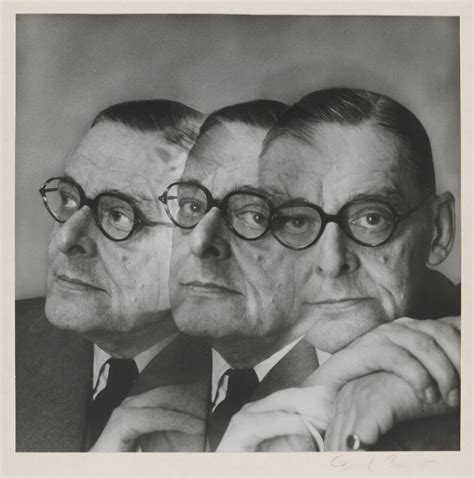

Source: Photographic portrait of Eliot by Cecil Beaton (National Portrait Gallery, UK)The grail has a long and varied literary history, possibly

beginning with early fertility rituals. In the 12th century, it was given Christian

meaning through Chrétien de Troyes’ early medieval romance Perceval. It is also the

holy object sought by the Arthurian knights, popularized in Thomas Malory’s Le Morte

d'Arthur (1485). The grail in Western Christian contexts is associated with the

resurrection of Jesus, specifically the cup that was used to hold the blood of

Christ. Throughout medieval Arthurian romance, the grail was guarded by the Fisher

King, a Christ-like character, depicted as infertile or wounded—which also becomes a

metaphor for the state of his kingdom. His wounds (and those of the land) will be

healed when the quest is completed by the hero asking the Fisher King the right

question: whom does the grail serve? There are many variations of the story, from

many different cultural contexts. Eliot uses the grail quest to heal the Fisher King

as a broad metaphor for the wounded modern world, torn apart by modernity and the

cataclysmic violence of the Great War. You can see something of the style of modernism in the second photographic portrait of Eliot here, by Cecil Beaton (1956), housed in the National Portrait Gallery UK.

Source: Photographic portrait of Eliot by Cecil Beaton (National Portrait Gallery, UK)The grail has a long and varied literary history, possibly

beginning with early fertility rituals. In the 12th century, it was given Christian

meaning through Chrétien de Troyes’ early medieval romance Perceval. It is also the

holy object sought by the Arthurian knights, popularized in Thomas Malory’s Le Morte

d'Arthur (1485). The grail in Western Christian contexts is associated with the

resurrection of Jesus, specifically the cup that was used to hold the blood of

Christ. Throughout medieval Arthurian romance, the grail was guarded by the Fisher

King, a Christ-like character, depicted as infertile or wounded—which also becomes a

metaphor for the state of his kingdom. His wounds (and those of the land) will be

healed when the quest is completed by the hero asking the Fisher King the right

question: whom does the grail serve? There are many variations of the story, from

many different cultural contexts. Eliot uses the grail quest to heal the Fisher King

as a broad metaphor for the wounded modern world, torn apart by modernity and the

cataclysmic violence of the Great War. You can see something of the style of modernism in the second photographic portrait of Eliot here, by Cecil Beaton (1956), housed in the National Portrait Gallery UK.

Eliot’s poem is as challenging--and rewarding for the curious reader--as it is influential; however, it can be read fruitfully without a deep understanding of the literary tradition that informs it. For a detailed discussion of the many allusions and other references in The Waste Land, see Allyson Booth’s Reading The Waste Land from the Bottom Up (2015). The first pages of each chapter are available as free preview, but your institution may have electronic access to the book as a whole.

Source: Photograph of the Somme battlefield, 1916 (Imperial War Museum)

Source: Photograph of the Somme battlefield, 1916 (Imperial War Museum)