Headnote for Walt Whitman

By

John O'Brien

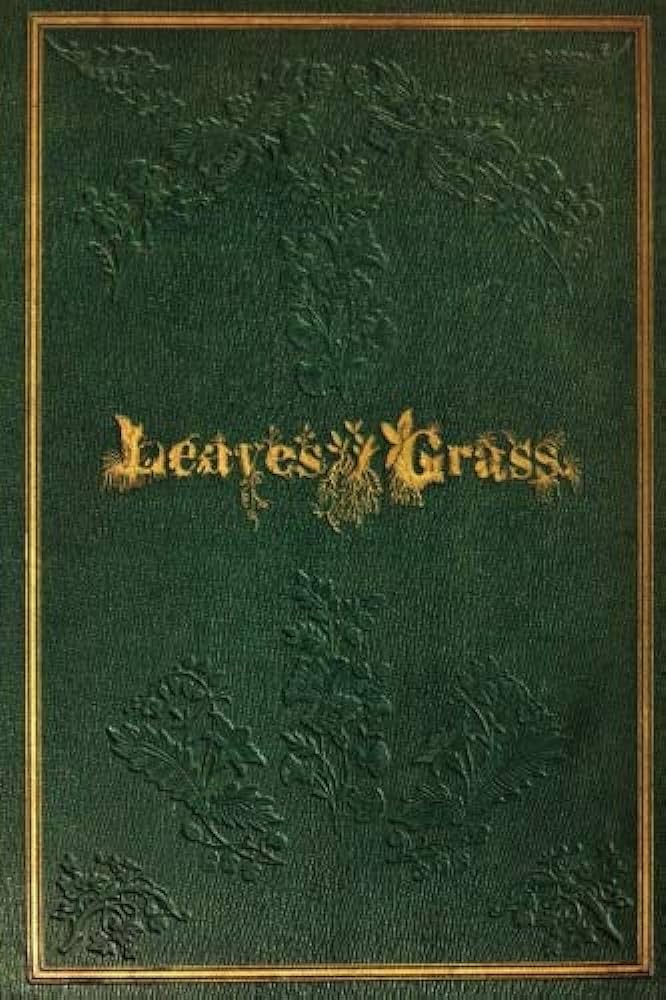

Imagine that it is the summer of 1855, and that you have wandered into a book shop in Brooklyn, New York. On a front table, along with other just-published books, you see a slender volume with a distinctive, embossed and gilded green cover. The title is Leaves of Grass.

Source: Cover of 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass from Walt Whitman Archive.

You are intrigued; is this a book about gardening, maybe? Opening the book, you are surprised to discover that this is a book of poetry, and you turn to a poem, also entitled “Leaves of Grass.” It is unlike any poem that you have ever seen before:

Source: Cover of 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass from Walt Whitman Archive.

You are intrigued; is this a book about gardening, maybe? Opening the book, you are surprised to discover that this is a book of poetry, and you turn to a poem, also entitled “Leaves of Grass.” It is unlike any poem that you have ever seen before:

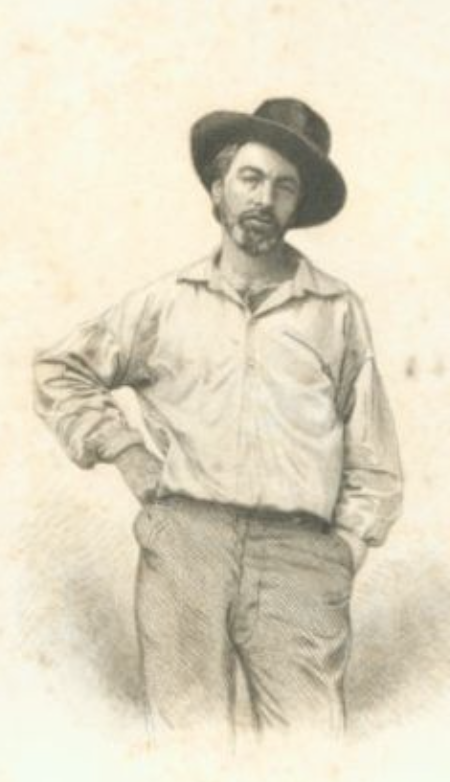

And so on: pages and pages of beautiful, hypnotic verse, spoken by voice that invites the reader in to celebrate a shared world of sensual pleasures, among them the sheer pleasure of language itself. No author is identified on the title page. But there is a portrait of a man in the place where author’s portraits tend to be. This too is stange: the man is not dressed in the kind of respectable suit that you would expect, but in workingman’s clothes, with his undershirt visible. You are intrigued; you purchase the book.

The author, of course, was Walt Whitman, and Leaves of Grass would become one of the most important works in all of American literature. The book seemed to come out of nowhere. Whitman was at this point 36 years old, unmarried and working odd construction jobs and living with his parents in Brooklyn. He had been a printer, a schoolteacher, and newspaper editor in Brooklyn and, for a brief time, New Orleans. To this point, his most substantial published work had been two novels: Franklin Evans, The Inebriate, published in a periodical called the New World in 1842 and a serialized novel, The Life and Adventures of Jack Engel: An Auto-Biography, published in the New York Sunday Dispatch in March and April 1852. He had contributed dozens of stories, poems, editorials, and reviews in papers in New York and Brooklyn, and become well known in literary circles in both cities. Leaves of Grass was something quite different than anything he had published before: a full-sized book, of poetry that did not always look like poetry, in a voice that was very different from any poetic voice that had been heard before. The lines vary from very short to extremely long. There are very few rhymes, but the rhythms of the poem are beautiful, like incantations or verses from the King James Bible. This is poetry that is very accessible, with a vocabulary drawn largely from everyday speech. "Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?" the poet asks, speaking to a reader who comes to poetry as an experience rooted in, not in schools, but in the real world.

Source: Frontispiece portrait of Walt Whitman, from 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass, from Walt Whitman Archive

Source: Frontispiece portrait of Walt Whitman, from 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass, from Walt Whitman Archive

Whitman set out to become what he called an “American Bard,” the poet of a nation that still felt new in his lifetime; as an adult, Whitman fondly recalled being hoisted as a child on the shoulders of Lafayette during the Revolutionary War hero’s visit to Brooklyn in 1826. He was responding to the call that Ralph Waldo Emerson had made in his essay "The Poet" for a native-born poet who could describe the richness of the nation: "America is a poem in our eyes," wrote Emerson, "its ample geography dazzles the imagination, and it will not wait long for metres." Leaves of Grass is Whitman's answer, the "metres" that Emerson imagined would correspond to America's amplitude; as Whitman remembered years later, "I was simmering, simmering, simmering; Emerson brought me to a boil." Whitman was acutely aware, though, that the integrity of that nation was being challenged even as he was writing, as the question of the future of slavery was coming to a head in the 1850s, with the question of whether slavery would be extended into territories that had been conquered from Mexico dividing the country, and the Fugitive Slave Act, which required even citizens of free states to return people who had escaped bondage back to their enslavers spurring the abolitionist movement. Whitman never wrote openly about his political opinions. But Leaves of Grass makes it clear that he wanted to promoted a radically democratic vision, where all the people of the United States were equal, at least in his poetic imagination, if not under the law. The figure of "leaves of grass" seems to be a way of describing a combination of individuality and collectivity, the discrete blades of a field having their own integrity while also making up a broad and unified expanse:

Or I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic, And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones, Growing among black folks as white.In 1855, incorporationg African-Americans into this "uniform hierogloyphic" was a radical statement of imaginative sympathy. The integrity of the nation that Whitman celebrated would be tested a few years after the first edition of Leaves of Grass by the outbreak of the American Civil War. Whitman moved to Washington, where he held clerical jobs and volunteered in hospitals to help care for wounded soldiers. Whitman maintained his faith in the project of American democracy through the war and after, and saw his own role as sustaining that project in imagination and verse.

Another way in which Whitman is both radically expansive and also somewhat evasive in the way that he describes sexuality. Throughout his poetry, Whitman celebrates our embodied selves: nothing about the human body is shameful, every human body is beautiful because it is part of the same creation. Sexuality is glorious as well, and Whitman's poetry is more openly positive towards all forms of sexual desire than any American poetry that had come before it. Whitman never married, and although he claimed to have loved women, it seems clear that he had little interest in conventional forms of heterosexual romance. There was no real thing as a gay identity in his lifetime, but it does seem that Whitman's strongest erotic impulses were towards other men, and his longest-term relationship was with a much younger man named Peter Doyle, an Irish immigrant who was a conductor on a Washington bus when they met. Sexuality was one of the other domains where Whitman was determined to be radically inclusive, open to all kinds of people and experience.

Leaves of Grass has been an influence on many American poets, establishing a line of loose-limbed, colloquial verse that runs from Whitman through Edna St. Vincent Millay, Allen Ginsberg and many others. Whitman's works have been set to music by something like 500 different composers.

Multiple editions of Leaves of Grass followed that first publication in Brooklyn in 1855. In each one, Whitman revised and expanded, adding new poems, rearranging them, giving them new names. The central poem in each version, and the most important poem of Whitman’s career, is the poem that became known as “Song of Myself,” which celebrates Whitman, America, the human body, and life itself. Our edition of Whitman’s poems is taken from the last edition of Leaves of Grass, published in 1892.