Fantomina; or, Love in a Maze

By

Eliza Haywood

OR,

LOVE in a Maze.

BEING A

Secret Historysecret_historysecret_historyWhile there are many critical understandings of the secret history in literature, as the essays in The Secret History in Literature: 1660-1820 (2017) suggest, the genre usually offers a glimpse into the secret lives of public individuals. In the amatory tradition of Fantomina, this "private" side is typically filled with sexual or political intrigue. - [TH]

OF AN

AMOUR

Between Two

PERSONS OF CONDITION.

By Mrs. ELIZA HAYWOOD.author author

Source: Engraved portrait of Haywood Eliza Haywood (c.1693-1756) was a

prolific author, actor, and publisher of the early- to mid-eighteenth century. She

is most famous, today, for her novels and novellas, among which Fantominais numbered. The image included here, via

Wikimedia Commons, is an engraved frontispiece portrait by George Vertue.

Haywood wrote in a number of different genres, including amatory fiction, domestic

fiction, and essay. - [TH]

Source: Engraved portrait of Haywood Eliza Haywood (c.1693-1756) was a

prolific author, actor, and publisher of the early- to mid-eighteenth century. She

is most famous, today, for her novels and novellas, among which Fantominais numbered. The image included here, via

Wikimedia Commons, is an engraved frontispiece portrait by George Vertue.

Haywood wrote in a number of different genres, including amatory fiction, domestic

fiction, and essay. - [TH]In Love the Victors from the Vanquish'd fly. They fly that wound, and they pursue that dye. WALLER.

wallerThis epigraph is composed of the last couplet from "To A. H: Of the Different Successe of Their Loves," a poem by Edmund Waller (1606-1687). Waller's poem, published in 1645, takes a Petrarchan perspective of the relationship between the male lover and the female beloved. This couplet was oft-quoted during the period, and features in George Etheredge's Restoration comedy Man of Mode, where it is spoken by the protagonist Dorimant. Read more about Waller at Encyclopaedia Britannica. - [TH]

London:

Printed for jun. at the Black-Swan

without Temple-Bar, and S. CHAPMAN, at

the Angel in Pallmall. M.DCC.XXV.

[257] FANTOMINA:

OR,

LOVE in a Maze.

A YOUNG Lady of distinguished Birth, Beauty, Wit, and Spirit, happened to be in a

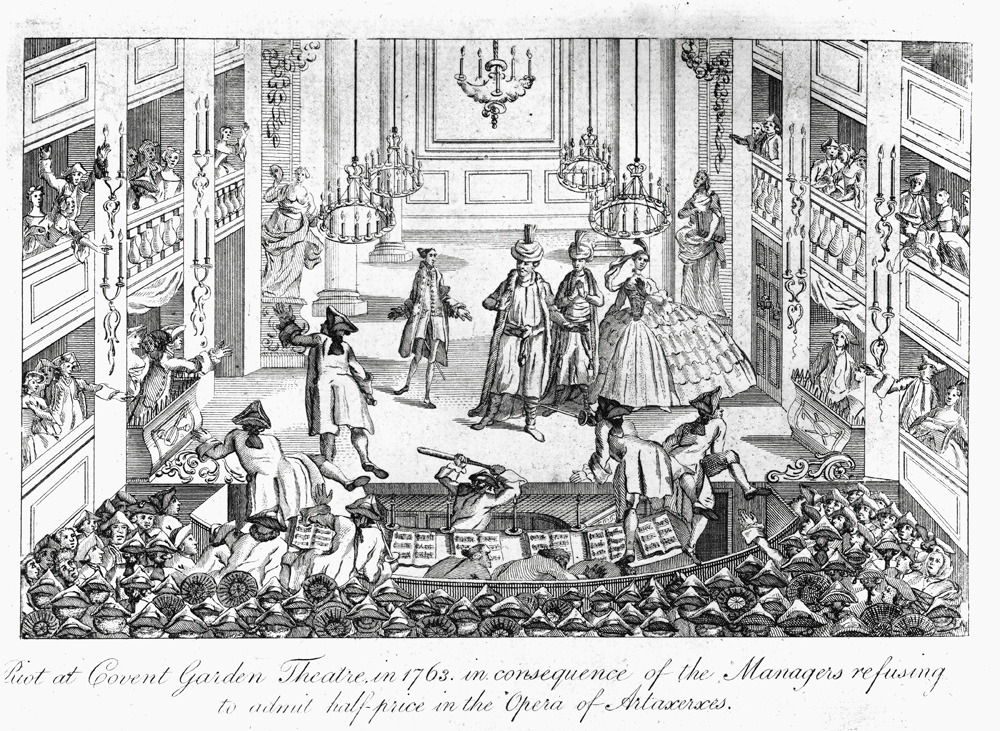

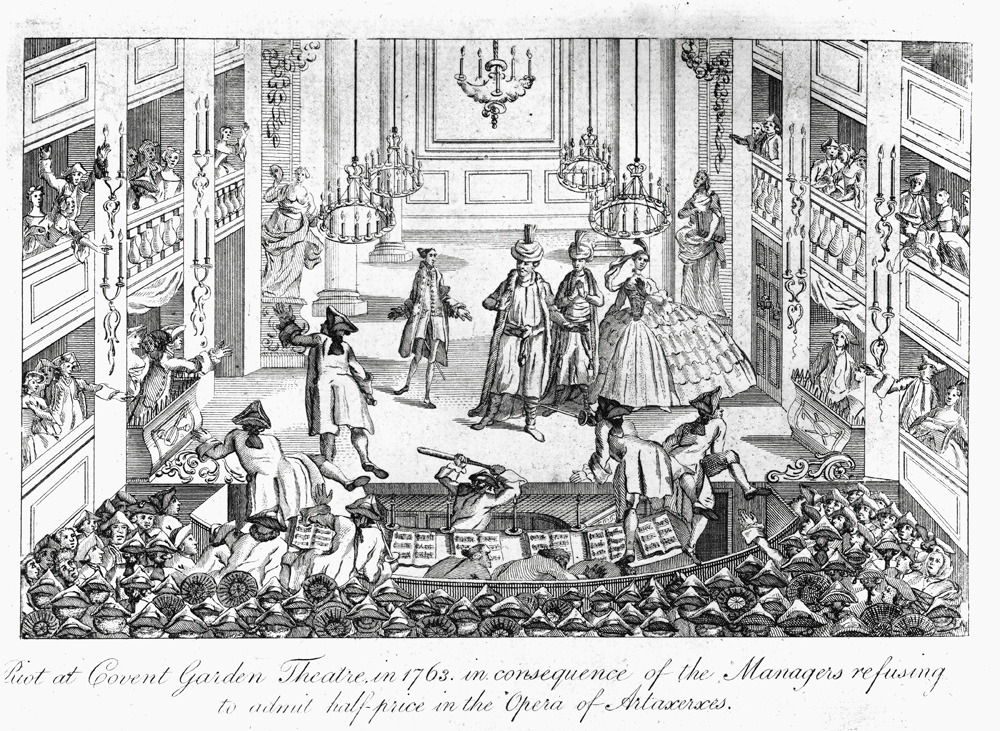

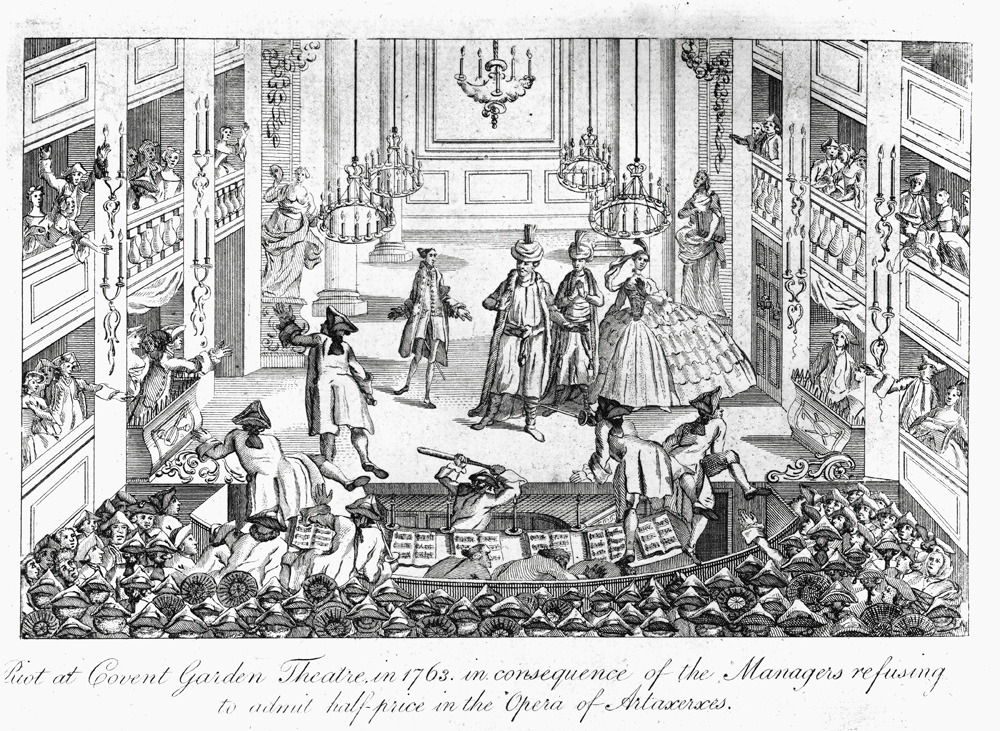

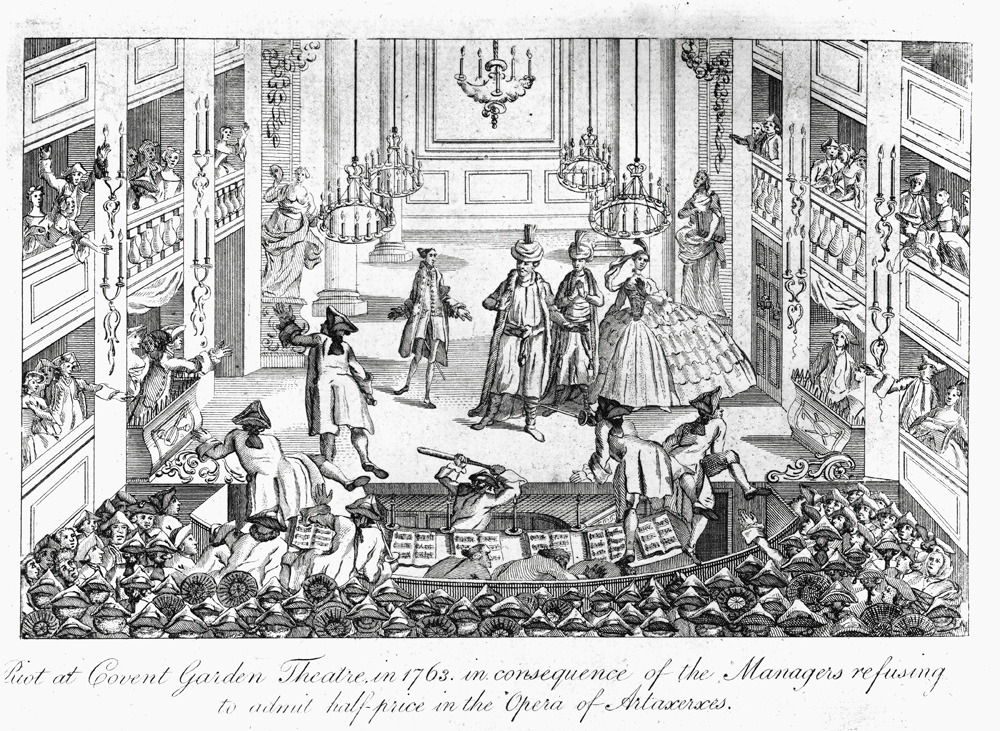

Boxboxbox Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatrePlayhouses

during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in England organized seating

according to price and social status. Boxes were the most expensive of seating

areas, and could hold several people in style. The image included here, from

the Victoria and Albert Museum, depicts a famous riot at Covent Garden

theater during a performance of the opera Artaxerxes in

1763. For more information about the development of theater in the eighteenth

century, see Andrew Dickson's introduction at the British Library. - [TH] one

Night at the Playhouse; where, though there were a great Number of celebrated ToaststoaststoastsAccording to the OED, a

"toast" is a "[a] lady who is named as the person to whom a company is requested

to drink; often one who is the reigning belle of the season" (n2.1). - [TH], she

perceived several Gentlemen extremely pleased themselves with entertaining a Woman

who sat in a Corner of the PitpitpitThe "pit" was a

mixed-sex seating area in the eighteenth-century, notable for its energy and

activity. According to The Oxford Companion to Theatre and

Performance, the "pit occupied the floor of the theatre at a lower level

than the stage and, unlike the standing pit of earlier public theatres, contained

rows of backless benches set on a raked floor. Seats in the pit were half the

price of a seat in the box and attracted a mixed audience of men and women. The

activity of the audience in the pit and the behaviour of the occupants of the

boxes, especially with the King present, were part of the theatregoing spectacle."

Prostitutes, wits, and rakes frequented the pit and the middle galleries. For more

information, see Douglas Canfield's introduction to The Broadview Anthology

of Restoration and Early Eighteenth-Century Drama

(vxiii). - [TH], and, by her Air and Manner of receiving them, might easily be known

to be one of those who come there for no other Purpose, than to create Acquaintance

with as many as seem desirous of it. She could not help testifying her Contempt of

Men, who, regardless either of the Play, or Circle, threw away their Time in such a

Manner, to some Ladies that sat by her: But they, either less surprised by being more

accustomed to such Sights, than she who had been bred for the most Part in the

Country, or not of a Disposition to consider any Thing very deeply, took but little

Notice of it. She still thought of it, however; and the longer she reflected on it,

the greater was her Wonder, that Men, some of whom she knew were accounted to have

Wit, should have Tastes so 258 very Depraved. – This excited a Curiosity in

her to know in what Manner these Creatures were address'd:– She was young, a Stranger

to the World, and consequently to the Dangers of it; and having no Body in Town, at

that Time, to whom she was oblig'd to be accountable for her Actions, did in every

Thing as her Inclinations or Humours render'd most agreeable to her: Therefore

thought it not in the least a Fault to put in practice a little Whim which came

immediately into her Head, to dress herself as near as she could in the Fashion of

those Women who make sale of their Favours, and set herself in the Way of being

accosted as such a one, having at that Time no other Aim, than the Gratification of

an innocent Curiosity.— She had no sooner design'd this Frolick, than she put it in

Execution; and muffling her HoodshoodshoodsThroughout

the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, hoods and

hooded cloaks were both practical and fashionable garments for women. In

the winter, hoods and masks protected the body from icy air, and they generally

allowed women more freedom to move un-seen throughout the city, as described in

this article from the BBC's History

Magazine. - [TH] over her Face, went the next Night into the Gallery-BoxgallerygalleryThe gallery-box or middle

gallery is a seating area in cost between pit and box seats. Servants often sat in

the inexpensive upper gallery seats. When Fantomina goes again tho the playhouse

on her "frolick," she sits in the gallery areas that signify her sexual

availability. Often, sex workers found partners and keepers at the playhouse,

earning the theater a reputation for sexual display. - [TH], and practising as

much as she had observ'd, at that Distance, the Behaviour of that Woman, was not long

before she found her Disguise had answer'd the Ends she wore it for: – A Crowd of

Purchasers of all Degrees and Capacities were in a Moment gather'd about her, each

endeavouring to out-bid the other, in offering her a Price for her Embraces. – She

listen'd to 'em all, and was not a little diverted in her Mind at the Disappointment

she shou'd give to so many, each of which thought himself secure of gaining her. –

She was told by 'em all, that she was the most lovely Woman in the World; and some

cry'd, Gad, she is mighty like my fine Lady Such-a-one, – naming her

own Name. She was naturally vain, and receiv'd no small Pleasure in hearing herself

prais'd, tho' in the Person of another, and a suppos'd Prostitute; but she dispatch'd

as soon as she cou'd all that had hitherto attack'd her, when she saw the

accomplish'd BeauplaisirbeauplaisirbeauplaisirBeauplaisir is a French portmanteau word meaning "beautiful pleasure." Beau was

also a generic term in the eighteenth century for a lady's suitor or sweetheart,

according to the OED. - [TH] was making his Way thro' the Crowd as fast as he was

able, to reach the Bench she sat on. She had often seen him in the Drawing-Roomdrawing_roomdrawing_roomThe drawing or "withdrawing" room was a room in the home of

a wealthier class of people to which women would "withdraw" after dinner, to brew

tea and converse. Later, the male contingent would join the women in the drawing

room for polite conversation and mingling. For more information on the history and

evolution of the drawing room, see this review of Jeremy Musson's Drawing

Room. - [TH], had talk'd with him; but then her Quality and reputed

Virtue kept him from using her with that Freedom she now expected he wou'd 259 do, and had discover'd something in him, which had made her often think

she shou'd not be displeas'd, if he wou'd abate some Part of his Reserve. – Now was

the Time to have her Wishes answer'd: – He look'd in her Face, and fancy'd, as many

others had done, that she very much resembled that Lady whom she really was; but the

vast Disparity there appear'd between their Characters, prevented him from

entertaining even the most distant Thought that they cou'd be the same. – He

address'd her at first with the usual SalutationssalutationssalutationsSalutations refer to

customary greetings. - [TH] of her pretended Profession, as, Are you

engag'd, Madam? – Will you permit me to wait on you home after the Play? – By

Heaven, you are a fine Girl! – How long have you us'd this House? – And

such like Questions; but perceiving she had a Turn of Wit, and a genteelgenteelgenteelUsed here as an

adjective, "genteel" refers to a quality of polite refinement thought to be

possessed by those of the gentry class. According to this review of Peter

Cross's The Origins of the English Gentry, the gentry

class is "a type of lesser nobility, based on landholding," that often

dispensed justice in the locality and wielded great social power. - [TH]

Manner in her RailleryrailleryrailleryAccording to the OED, raillery refers to "[g]ood-humoured ridicule or banter,"

which can sometimes be more satirical or mocking. - [TH], beyond what is

frequently to be found among those Wretches, who are for the most part Gentlewomen

but by Necessity, few of 'em having had an Education suitable to what they affect to

appear, he chang'd the Form of his Conversation, and shew'd her it was not because he

understood no better, that he had made use of Expressions so little polite. – In

fine, they were infinitely charm'd with each other: He was transported to find so

much Beauty and Wit in a Woman, who he doubted not but on very easy Terms he might

enjoy; and she found a vast deal of Pleasure in conversing with him in this free and

unrestrain'd Manner. They pass'd their Time all the Play with an equal Satisfaction;

but when it was over, she found herself involv'd in a Difficulty, which before never

enter'd into her Head, but which she knew not well how to get over. – The Passion he

profess'd for her, was not of that humble Nature which can be content with distant

Adorations: – He resolv'd not to part from her without the Gratifications of those

Desires she had inspir'd; and presuming on the Liberties which her suppos'd Function

allow'd off, told her she must either go with him to some convenient House of his

procuring, or permit him to wait on her to her own 260 Lodgings. – Never had she been in such a Dilemma:

Three or four Times did she open her Mouth to confess her real Qualityqualityquality"Quality" is a difficult concept to grasp;

in the eighteenth century, it typically referred to rank or social position, and

more particularly, noble or high social position, as indicated by senses 4 and 5

in the OED. - [TH]; but the influence of her ill Stars prevented it, by putting an

Excuse into her Head, which did the Business as well, and at the same Time did not

take from her the Power of seeing and entertaining him a second Time with the same

Freedom she had done this. – She told him, she was under Obligations to a Man

who maintain'd her, and whom she durst not disappoint, having promis'd to meet him

that Night at a House hard by. – This Story so like what those Ladies

sometimes tell, was not at all suspected by Beauplaisir; and assuring her he wou'd be

far from doing her a Prejudice, desir'd that in return for the Pain he shou'd suffer

in being depriv'd of her Company that Night, that she wou'd order her Affairs, so as

not to render him unhappy the next. She gave a solemn Promise to be in the same Box

on the Morrow Evening; and they took Leave of each other; he to the Tavern to drown

the Remembrance of his Disappointment; she in a Hackney-ChairchairchairA hackney or sedan chair was a hireable mode of

transportation that consisted of a single enclosed seat carried, on poles, by two

strong men. It was small enough to enter into the front doors of a well-appointed

house, thus ensuring secresy. Read more about the hackney or sedan chair in this article from Bath Magazine. The image

included here shows an early eighteenth-century French sedan chair, without the

horizontal carrying poles, housed

in the VAM.

Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatrePlayhouses

during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in England organized seating

according to price and social status. Boxes were the most expensive of seating

areas, and could hold several people in style. The image included here, from

the Victoria and Albert Museum, depicts a famous riot at Covent Garden

theater during a performance of the opera Artaxerxes in

1763. For more information about the development of theater in the eighteenth

century, see Andrew Dickson's introduction at the British Library. - [TH] one

Night at the Playhouse; where, though there were a great Number of celebrated ToaststoaststoastsAccording to the OED, a

"toast" is a "[a] lady who is named as the person to whom a company is requested

to drink; often one who is the reigning belle of the season" (n2.1). - [TH], she

perceived several Gentlemen extremely pleased themselves with entertaining a Woman

who sat in a Corner of the PitpitpitThe "pit" was a

mixed-sex seating area in the eighteenth-century, notable for its energy and

activity. According to The Oxford Companion to Theatre and

Performance, the "pit occupied the floor of the theatre at a lower level

than the stage and, unlike the standing pit of earlier public theatres, contained

rows of backless benches set on a raked floor. Seats in the pit were half the

price of a seat in the box and attracted a mixed audience of men and women. The

activity of the audience in the pit and the behaviour of the occupants of the

boxes, especially with the King present, were part of the theatregoing spectacle."

Prostitutes, wits, and rakes frequented the pit and the middle galleries. For more

information, see Douglas Canfield's introduction to The Broadview Anthology

of Restoration and Early Eighteenth-Century Drama

(vxiii). - [TH], and, by her Air and Manner of receiving them, might easily be known

to be one of those who come there for no other Purpose, than to create Acquaintance

with as many as seem desirous of it. She could not help testifying her Contempt of

Men, who, regardless either of the Play, or Circle, threw away their Time in such a

Manner, to some Ladies that sat by her: But they, either less surprised by being more

accustomed to such Sights, than she who had been bred for the most Part in the

Country, or not of a Disposition to consider any Thing very deeply, took but little

Notice of it. She still thought of it, however; and the longer she reflected on it,

the greater was her Wonder, that Men, some of whom she knew were accounted to have

Wit, should have Tastes so 258 very Depraved. – This excited a Curiosity in

her to know in what Manner these Creatures were address'd:– She was young, a Stranger

to the World, and consequently to the Dangers of it; and having no Body in Town, at

that Time, to whom she was oblig'd to be accountable for her Actions, did in every

Thing as her Inclinations or Humours render'd most agreeable to her: Therefore

thought it not in the least a Fault to put in practice a little Whim which came

immediately into her Head, to dress herself as near as she could in the Fashion of

those Women who make sale of their Favours, and set herself in the Way of being

accosted as such a one, having at that Time no other Aim, than the Gratification of

an innocent Curiosity.— She had no sooner design'd this Frolick, than she put it in

Execution; and muffling her HoodshoodshoodsThroughout

the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, hoods and

hooded cloaks were both practical and fashionable garments for women. In

the winter, hoods and masks protected the body from icy air, and they generally

allowed women more freedom to move un-seen throughout the city, as described in

this article from the BBC's History

Magazine. - [TH] over her Face, went the next Night into the Gallery-BoxgallerygalleryThe gallery-box or middle

gallery is a seating area in cost between pit and box seats. Servants often sat in

the inexpensive upper gallery seats. When Fantomina goes again tho the playhouse

on her "frolick," she sits in the gallery areas that signify her sexual

availability. Often, sex workers found partners and keepers at the playhouse,

earning the theater a reputation for sexual display. - [TH], and practising as

much as she had observ'd, at that Distance, the Behaviour of that Woman, was not long

before she found her Disguise had answer'd the Ends she wore it for: – A Crowd of

Purchasers of all Degrees and Capacities were in a Moment gather'd about her, each

endeavouring to out-bid the other, in offering her a Price for her Embraces. – She

listen'd to 'em all, and was not a little diverted in her Mind at the Disappointment

she shou'd give to so many, each of which thought himself secure of gaining her. –

She was told by 'em all, that she was the most lovely Woman in the World; and some

cry'd, Gad, she is mighty like my fine Lady Such-a-one, – naming her

own Name. She was naturally vain, and receiv'd no small Pleasure in hearing herself

prais'd, tho' in the Person of another, and a suppos'd Prostitute; but she dispatch'd

as soon as she cou'd all that had hitherto attack'd her, when she saw the

accomplish'd BeauplaisirbeauplaisirbeauplaisirBeauplaisir is a French portmanteau word meaning "beautiful pleasure." Beau was

also a generic term in the eighteenth century for a lady's suitor or sweetheart,

according to the OED. - [TH] was making his Way thro' the Crowd as fast as he was

able, to reach the Bench she sat on. She had often seen him in the Drawing-Roomdrawing_roomdrawing_roomThe drawing or "withdrawing" room was a room in the home of

a wealthier class of people to which women would "withdraw" after dinner, to brew

tea and converse. Later, the male contingent would join the women in the drawing

room for polite conversation and mingling. For more information on the history and

evolution of the drawing room, see this review of Jeremy Musson's Drawing

Room. - [TH], had talk'd with him; but then her Quality and reputed

Virtue kept him from using her with that Freedom she now expected he wou'd 259 do, and had discover'd something in him, which had made her often think

she shou'd not be displeas'd, if he wou'd abate some Part of his Reserve. – Now was

the Time to have her Wishes answer'd: – He look'd in her Face, and fancy'd, as many

others had done, that she very much resembled that Lady whom she really was; but the

vast Disparity there appear'd between their Characters, prevented him from

entertaining even the most distant Thought that they cou'd be the same. – He

address'd her at first with the usual SalutationssalutationssalutationsSalutations refer to

customary greetings. - [TH] of her pretended Profession, as, Are you

engag'd, Madam? – Will you permit me to wait on you home after the Play? – By

Heaven, you are a fine Girl! – How long have you us'd this House? – And

such like Questions; but perceiving she had a Turn of Wit, and a genteelgenteelgenteelUsed here as an

adjective, "genteel" refers to a quality of polite refinement thought to be

possessed by those of the gentry class. According to this review of Peter

Cross's The Origins of the English Gentry, the gentry

class is "a type of lesser nobility, based on landholding," that often

dispensed justice in the locality and wielded great social power. - [TH]

Manner in her RailleryrailleryrailleryAccording to the OED, raillery refers to "[g]ood-humoured ridicule or banter,"

which can sometimes be more satirical or mocking. - [TH], beyond what is

frequently to be found among those Wretches, who are for the most part Gentlewomen

but by Necessity, few of 'em having had an Education suitable to what they affect to

appear, he chang'd the Form of his Conversation, and shew'd her it was not because he

understood no better, that he had made use of Expressions so little polite. – In

fine, they were infinitely charm'd with each other: He was transported to find so

much Beauty and Wit in a Woman, who he doubted not but on very easy Terms he might

enjoy; and she found a vast deal of Pleasure in conversing with him in this free and

unrestrain'd Manner. They pass'd their Time all the Play with an equal Satisfaction;

but when it was over, she found herself involv'd in a Difficulty, which before never

enter'd into her Head, but which she knew not well how to get over. – The Passion he

profess'd for her, was not of that humble Nature which can be content with distant

Adorations: – He resolv'd not to part from her without the Gratifications of those

Desires she had inspir'd; and presuming on the Liberties which her suppos'd Function

allow'd off, told her she must either go with him to some convenient House of his

procuring, or permit him to wait on her to her own 260 Lodgings. – Never had she been in such a Dilemma:

Three or four Times did she open her Mouth to confess her real Qualityqualityquality"Quality" is a difficult concept to grasp;

in the eighteenth century, it typically referred to rank or social position, and

more particularly, noble or high social position, as indicated by senses 4 and 5

in the OED. - [TH]; but the influence of her ill Stars prevented it, by putting an

Excuse into her Head, which did the Business as well, and at the same Time did not

take from her the Power of seeing and entertaining him a second Time with the same

Freedom she had done this. – She told him, she was under Obligations to a Man

who maintain'd her, and whom she durst not disappoint, having promis'd to meet him

that Night at a House hard by. – This Story so like what those Ladies

sometimes tell, was not at all suspected by Beauplaisir; and assuring her he wou'd be

far from doing her a Prejudice, desir'd that in return for the Pain he shou'd suffer

in being depriv'd of her Company that Night, that she wou'd order her Affairs, so as

not to render him unhappy the next. She gave a solemn Promise to be in the same Box

on the Morrow Evening; and they took Leave of each other; he to the Tavern to drown

the Remembrance of his Disappointment; she in a Hackney-ChairchairchairA hackney or sedan chair was a hireable mode of

transportation that consisted of a single enclosed seat carried, on poles, by two

strong men. It was small enough to enter into the front doors of a well-appointed

house, thus ensuring secresy. Read more about the hackney or sedan chair in this article from Bath Magazine. The image

included here shows an early eighteenth-century French sedan chair, without the

horizontal carrying poles, housed

in the VAM. Source: Early 18th-century French sedan chair (VAM) - [TH] hurry'd home to

indulge Contemplation on the Frolick she had taken, designing nothing less on her

first Reflections, than to keep the Promise she had made him, and hugging herself

with Joy, that she had the good Luck to come off undiscover'd.

Source: Early 18th-century French sedan chair (VAM) - [TH] hurry'd home to

indulge Contemplation on the Frolick she had taken, designing nothing less on her

first Reflections, than to keep the Promise she had made him, and hugging herself

with Joy, that she had the good Luck to come off undiscover'd.

But these Cogitationscogitationscogitations"Cogitations" are thoughts; often, the word contains a humourously exaggerated connotation. - [TH] were but of a short Continuance, they vanish'd with the Hurry of her Spirits, and were succeeded by others vastly different and ruinous: – All the Charms of Beauplaisir came fresh into her Mind; she languish'd, she almost dy'd for another Opportunity of conversing with him; and not all the Admonitions of her Discretion were effectual to oblige her to deny laying hold of that which offer'd itself the next Night. – She depended on the Strength of her Virtue, to bear her fate thro' Tryals more dangerous than she apprehended this to be, and never having been address'd by him as Lady, — was resolv'd to receive his DevoirsdevoirsdevoirsFrom the French word for duty, "devoirs" are dutiful addresses paid to someone out of respect or courtesy. See sense 4 in the OED. - [TH] as a Town-Mistress, imagining a world of Satisfaction to herself in engaging him in the Character 261 of such a one, and in observing the Surprise he would be in to find himself refused by a Woman, who he supposed granted her Favours without Exception. – Strange and unaccountable were the Whimsies she was possess'd of, – wild and incoherent her Desires, – unfix'd and undetermin'd her Resolutions, but in that of seeing Beauplaisir in the Manner she had lately done. As for her Proceedings with him, or how a second Time to escape him, without discovering who she was, she cou'd neither assure herself, nor whither or not in the last Extremity she wou'd do so. – Bent, however, on meeting him, whatever shou'd be the Consequence, she went out some Hours before the Time of going to the Playhouse, and took lodgingslodgingslodgingsFantomina explains that she rented rooms near the playhouse, which were centrally located and more expensive than houses or rooms in houses further afield. She would likely have rented the furnished first floor for between 2 and 4 guineas per week, according to John Trusler's late eighteenth-century London Adviser and Guide. For a sense of the cost of living in the period, see "Currency, Coinage and the Cost of Living" at the Old Bailey Online. For a good overview of early Georgian town houses, see this Google Arts and Culture Spotter's Guide. - [TH] in a House not very far from it, intending, that if he shou'd insist on passing some Part of the Night with her, to carry him there, thinking she might with more Security to her Honour entertain him at a Place where she was Mistress, than at any of his own chusing.

THE appointed Hour being arriv'd, she had the Satisfaction to find his Love in his Assiduity: He was there before her; and nothing cou'd be more tender than the Manner in which he accosted her: But from the first Moment she came in, to that of the Play being done, he continued to assure her no Consideration shou'd prevail with him to part from her again, as she had done the Night before; and she rejoic'd to think she had taken that Precaution of providing herself with a Lodging, to which she thought she might invite him, without running any Risque, either of her Virtue or Reputation. – Having told him she wou'd admit of his accompanying her home, he seem'd perfectly satisfy'd; and leading her to the Place, which was not above twenty Houses distant, wou'd have order'd a CollationcollationcollationA "collation," according to the OED, is a light, often cold meal of meats, fruits, and wine that has little to no need of preparation. - [TH] to be brought after them. But she wou'd not permit it, telling him she was not one of those who suffer'd themselves to be treated at their own Lodgings; and as soon as she was come in, sent a Servant, belonging to the HousehousehouseWhen renting furnished rooms, a lodger might bring their own servant or use the servants who work consistently at the house. Here, we learn that Fantomina did not bring her own servant, but drew on the services of those from whom she rented. - [TH], to provide a very handsome Supper, and Wine, and every Thing was 262 serv'd to Table in a Manner which shew'd the Director neither wanted Money, nor was ignorant how it shou'd be laid out.

THIS Proceeding, though it did not take from him the Opinion that she was what she appeared to be, yet it gave him Thoughts of her, which he had not before. – He believ'd her a Mistress, but believ'd her to be one of a superior Rank, and began to imagine the Possession of her would be much more Expensive than at first he had expected: But not being of a Humour to grudge any Thing for his Pleasures, he gave himself no further Trouble, than what were occasioned by Fears of not having Money enough to reach her Price, about him.

SUPPER being over, which was intermixed with a vast deal of amorous Conversation, he began to explain himself more than he had done; and both by his Words and Behaviour let her know, he would not be denied that Happiness the Freedoms she allow'd had made him hope. – It was in vain; she would have retracted the Encouragement she had given: – In vain she endeavoured to delay, till the next Meeting, the fulfilling of his Wishes: – She had now gone too far to retreat: – He was bold; – he was resolute: She fearful, – confus'd, altogether unprepar'd to resist in such Encounters, and rendered more so, by the extreme Liking she had to him. – Shock'd, however, at the Apprehension of really losing her HonourhonourhonourHonor, in this sense, is being used to refer to Fantomina's "virtue as regards sexual morality," according to sense 7 in the OED--or, "a reputation for this, one's good name." - [TH], she struggled all she could, and was just going to reveal the whole Secret of her Name and Quality, when the Thoughts of the Liberty he had taken with her, and those he still continued to prosecute, prevented her, with representing the Danger of being expos'd, and the whole Affair made a Theme for publick Ridicule. – Thus much, indeed, she told him, that she was a Virgin, and had assumed this Manner of Behaviour only to engage him. But that he little regarded, or if he had, would have been far from obliging him to desist; – nay, in the present burning Eagerness of Desire, 'tis probable, that had he been 263 acquainted both with who and what she really was, the Knowledge of her Birth would not have influenc'd him with Respect sufficient to have curb'd the wild Exuberance of his luxurious Wishes, or made him in that longing, – that impatient Moment, change the Form of his Addresses. In fine, she was undone; and he gain'd a Victory, so highly rapturous, that had he known over whom, scarce could he have triumphed more. Her Tears, however, and the Destraction she appeared in, after the ruinous Extasy was past, as it heighten'd his Wonder, so it abated his Satisfaction: – He could not imagine for what Reason a Woman, who, if she intended not to be a Mistress, had counterfeited the Part of one, and taken so much Pains to engage him, should lament a Consequence which she could not but expect, and till the last Test, seem'd inclinable to grant; and was both surpris'd and troubled at the Mystery. – He omitted nothing that he thought might make her easy; and still retaining an Opinion that the Hope of Interest had been the chief Motive which had led her to act in the Manner she had done, and believing that she might know so little of him, as to suppose, now she had nothing left to give, he might not make that Recompense she expected for her Favours: To put her out of that Pain, he pulled out of his Pocket a Purse of Gold, entreating her to accept of that as an Earnest of what he intended to do for her; assuring her, with ten thousand Protestations, that he would spare nothing, which his whole Estate could purchase, to procure her Content and Happiness. This Treatment made her quite forget the Part she had assum'd, and throwing it from her with an Air of Disdain, Is this a Reward (said she) for Condescensions, such as I have yeilded to? – Can all the Wealth you are possessed of, make a Reparation for my Loss of Honour? – Oh! no, I am undone beyond the Power of Heaven itself to help me! – She uttered many more such Exclamations; which the amaz'd Beauplaisir heard without being able to reply to, till by Degrees sinking 264 from that Rage of Temper, her Eyes resumed their softning Glances, and guessing at the Consternation he was in, No, my dear Beauplaisir, (added she,) your Love alone can compensate for the Shame you have involved me in; be you sincere and constant, and I hereafter shall, perhaps, be satisfy'd with my Fate, and forgive myself the Folly that betray'd me to you.

BEAUPLAISIR thought he could not have a better Opportunity than these Words gave him of enquiring who she was, and wherefore she had feigned herself to be of a Profession which he was now convinc'd she was not; and after he had made her thousand Vows of an Affection, as inviolable and ardent as she could wish to find in him, entreated she would inform him by what Means his Happiness has been brought about, and also to whom he was indebted for the Bliss he had enjoy'd. – Some remains of yet unextinguished Modesty, and Sense of Shame, made her Blush exceedingly at this Demand; but recollecting herself in a little Time, she told him so much of the Truth, as to what related to the Frolick she had taken of satisfying her Curiosity in what Manner Mistresses, of the Sort she appeared to be, were treated by those who addressed them; but forbore discovering her true Name and Quality, for the Reasons she had done before, resolving, if he boasted of this Affair, he should not have it in his Power to touch her Character: She therefore said she was the Daughter of a Country GentlemancountrycountryA country gentleman would be a member of the landed gentry, residing most likely in a country house or mansion where the business of the locality was often conducted. The country gentleman would likely have also had a town house in London. To read more about the country house, see Mark Girouard's Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural History (1978). - [TH], who was come to town to buy Cloaths, and that she was call'd Fantomina. He had no Reason to distrust the Truth of this Story, and was therefore satisfy'd with it; but did not doubt by the Beginning of her Conduct, but that in the End she would be in Reality, the Thing she so artfully had counterfeited; and had good Nature enough to pity the Misfortunes he imagin'd would be her Lot: But to tell her so, or offer his Advice in that Point, was not his Business, as least, as yet. 265

THEY parted not till towards Morning; and she oblig'd him to a willing Vow of visiting her the next Day at Three in the Afternoon. It was too late for her to go home that Night, therefore contented herself with lying there. In the Morning she sent for the Woman of the House to come up to her; and easily perceiving, by her Manner, that she was a Woman who might be influenced by Gifts, made her a Present of a Couple of Broad PiecespiecepieceA broad piece is a coin approximately the same as a pound, worth 20 shillings. It was called a "broad piece" because it was thicker and and bigger than newer coins, minted after 1663. See "A Note on British Money", included in the Broadview edition of Anti-Pamela and Shamela (50ff). - [TH], and desir'd her, that if the Gentleman, who had been there the night before, should ask any Questions concerning her, that he should be told, she was lately come out of the Country, had lodg'd there about a Fortnight, and that her Name was Fantomina. I shall (also added she) lie but seldom here; nor, indeed, ever come but in those Times when I expect to meet him: I would, therefore, have you order it so, that he may think I am but just gone out, if he should happen by any Accident to call when I am not here; for I would not, for the World, have him imagine I do not constantly lodge here. The Landlady assur'd her she would do every Thing as she desired, and gave her to understand she wanted not the Gift of Secrecy.

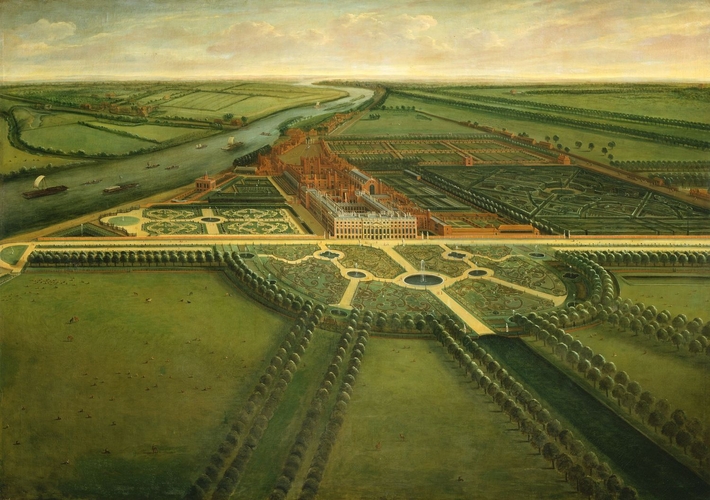

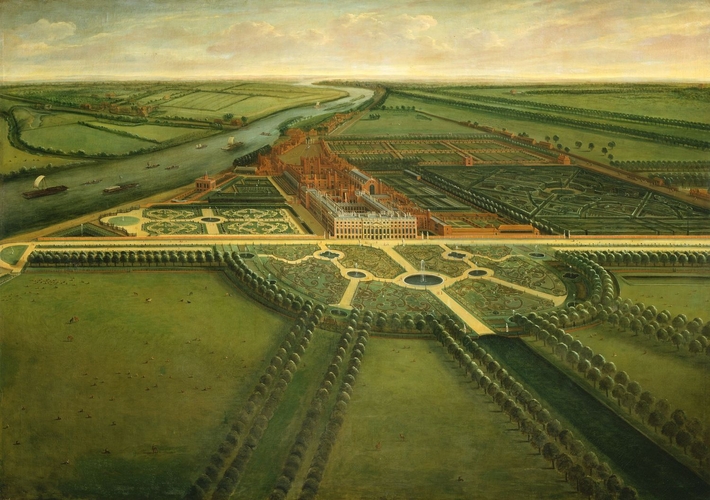

EVERY Thing being ordered at this Home for the Security of her Reputation, she

repaired to the other, where she easily excused to an unsuspecting Aunt, with whom

she boarded, her having been abroad all Night, saying, she went with a Gentleman and

his Lady in a Bargebargebarge Source: https://www.rct.uk/collection/404760/a-view-of-hampton-courtThe river Thames was a

source of work, pleasure, and transportation in the eighteenth century; it

connected many significant country towns to London, and access to Hampton Court

Palace as well as the many London pleasure gardens was primarily accomplished via

the river. To

learn more about the history of the Thames, see this BBC article by Andy

Dangerfield. The image included here, an early

eighteenth-century painting by Leonard Knyff via the Royal Collection

Trust, shows Hampton Court Palace and the barges passing on the river

Thames. - [TH],

to a little Country Seat of theirs up the River, all of them designing to return the

same Evening; but that one of the Bargemen happ'ning to be taken ill on the sudden,

and no other Waterman to be got that Night, they were oblig'd to tarry till Morning.

Thus did this Lady's Wit and Vivacity assist her in all, but where it was most

needful. – She had Discernment to forsee, and avoid all those Ills which might attend

the Loss of her Reputation, but was wholly blind to those of the Ruin of her Virtue;

and having managed her Affairs so as to secure the one, grew perfectly easy with the

Remembrance, 266she had forfeited the other. –

The more she reflected on the Merits of Beauplaisir, the more she excused herself for

what she had done; and the Prospect of that continued Bliss she expected to share

with him, took from her all Remorse for having engaged in an Affair which promised

her so much Satisfaction, and in which she found not the least Danger of Misfortune.

– If he is really (said she, to herself) the faithful, the constant Lover he

has sworn to be, how charming will be our Amour? – And if he should be false, grow

satiated, like other Men, I shall but, at the worst, have the private Vexation of

knowing I have lost him; – the IntreagueintrigueintrigueAccording to the OED, an "intrigue" is at once a secret

intimacy between lovers, as well as an intricate or maze-like contrivance,

perhaps enabling the clandestine romance. - [TH] being a Secret, my Disgrace

will be so too: – I shall hear no Whispers as I pass, – She is Forsaken: – The

odious Word Forsaken will never wound my Ears; nor will my Wrongs excite either

the Mirth or Pity of the talking World: – It will not be even in the Power of my

Undoer himself to triumph over me; and while he laughs at, and perhaps despises

the fond, the yielding Fantomina, he will revere and esteem the virtuous, the

reserv'd Lady. – In this Manner did she applaud her own Conduct, and exult

with the Imagination that she had more Prudence than all her Sex beside. And it must

be confessed, indeed, that she preserved an OEconomy in the management of this

Intreague, beyond what almost any Woman but herself ever did: In the first Place, by

making no Person in the World a Confident in it; and in the next, in concealing from

Beauplaisir himself the Knowledge who she was; for though she met him three or four

Days in a Week, at the Lodging she had taken for that Purpose, yet as much as he

employ'd her Time and Thoughts, she was never miss'd from any Assembly she had been

accustomed to frequent. – The Business of her Love has engross'd her till Six in the

Evening, and before Seven she has been dress'd in a different HabithabithabitA habit used in this sense refers to a particular garment or

mode of dress, often specific to a profession or activity. See the OED senses 1

and 2. - [TH], and in another Place. – Slippers, and a Nightgown loosely flowing,

has been the Garb in which he has left the languishing Fantomina; – Lac'd, and 267 adorn'd with all the Blaze of Jewels, has he, in less than an Hour

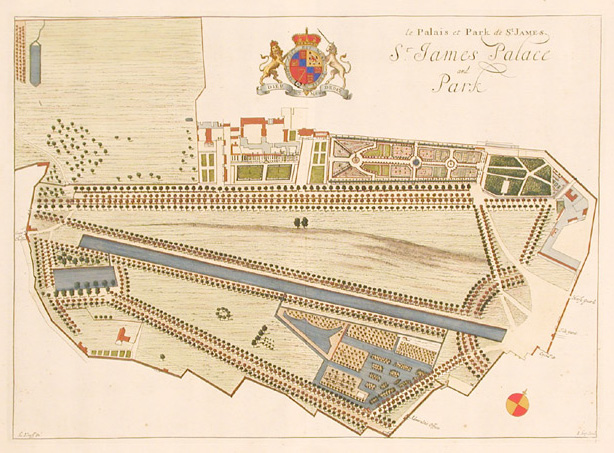

after, beheld at the Royal ChapelchapelchapelFantomina

here likely refers to the Chapel Royal at St. James's Palace. During the Georgian

period, the Chapel Royal became "a significant cultural centre." For more

information on the Chapel Royal, see this article by Carolyn Harris. - [TH], the Palace Gardensgardensgardens

Source: https://www.rct.uk/collection/404760/a-view-of-hampton-courtThe river Thames was a

source of work, pleasure, and transportation in the eighteenth century; it

connected many significant country towns to London, and access to Hampton Court

Palace as well as the many London pleasure gardens was primarily accomplished via

the river. To

learn more about the history of the Thames, see this BBC article by Andy

Dangerfield. The image included here, an early

eighteenth-century painting by Leonard Knyff via the Royal Collection

Trust, shows Hampton Court Palace and the barges passing on the river

Thames. - [TH],

to a little Country Seat of theirs up the River, all of them designing to return the

same Evening; but that one of the Bargemen happ'ning to be taken ill on the sudden,

and no other Waterman to be got that Night, they were oblig'd to tarry till Morning.

Thus did this Lady's Wit and Vivacity assist her in all, but where it was most

needful. – She had Discernment to forsee, and avoid all those Ills which might attend

the Loss of her Reputation, but was wholly blind to those of the Ruin of her Virtue;

and having managed her Affairs so as to secure the one, grew perfectly easy with the

Remembrance, 266she had forfeited the other. –

The more she reflected on the Merits of Beauplaisir, the more she excused herself for

what she had done; and the Prospect of that continued Bliss she expected to share

with him, took from her all Remorse for having engaged in an Affair which promised

her so much Satisfaction, and in which she found not the least Danger of Misfortune.

– If he is really (said she, to herself) the faithful, the constant Lover he

has sworn to be, how charming will be our Amour? – And if he should be false, grow

satiated, like other Men, I shall but, at the worst, have the private Vexation of

knowing I have lost him; – the IntreagueintrigueintrigueAccording to the OED, an "intrigue" is at once a secret

intimacy between lovers, as well as an intricate or maze-like contrivance,

perhaps enabling the clandestine romance. - [TH] being a Secret, my Disgrace

will be so too: – I shall hear no Whispers as I pass, – She is Forsaken: – The

odious Word Forsaken will never wound my Ears; nor will my Wrongs excite either

the Mirth or Pity of the talking World: – It will not be even in the Power of my

Undoer himself to triumph over me; and while he laughs at, and perhaps despises

the fond, the yielding Fantomina, he will revere and esteem the virtuous, the

reserv'd Lady. – In this Manner did she applaud her own Conduct, and exult

with the Imagination that she had more Prudence than all her Sex beside. And it must

be confessed, indeed, that she preserved an OEconomy in the management of this

Intreague, beyond what almost any Woman but herself ever did: In the first Place, by

making no Person in the World a Confident in it; and in the next, in concealing from

Beauplaisir himself the Knowledge who she was; for though she met him three or four

Days in a Week, at the Lodging she had taken for that Purpose, yet as much as he

employ'd her Time and Thoughts, she was never miss'd from any Assembly she had been

accustomed to frequent. – The Business of her Love has engross'd her till Six in the

Evening, and before Seven she has been dress'd in a different HabithabithabitA habit used in this sense refers to a particular garment or

mode of dress, often specific to a profession or activity. See the OED senses 1

and 2. - [TH], and in another Place. – Slippers, and a Nightgown loosely flowing,

has been the Garb in which he has left the languishing Fantomina; – Lac'd, and 267 adorn'd with all the Blaze of Jewels, has he, in less than an Hour

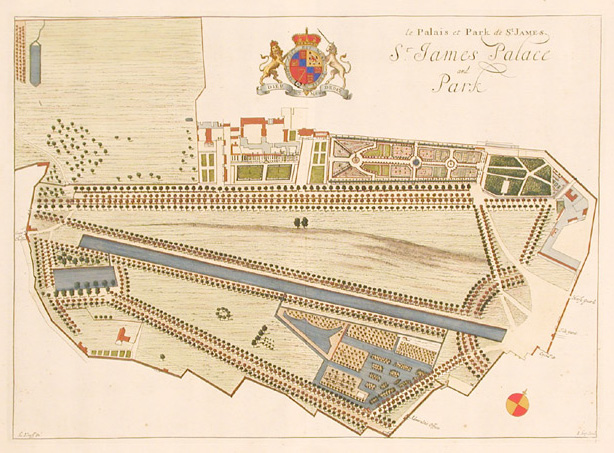

after, beheld at the Royal ChapelchapelchapelFantomina

here likely refers to the Chapel Royal at St. James's Palace. During the Georgian

period, the Chapel Royal became "a significant cultural centre." For more

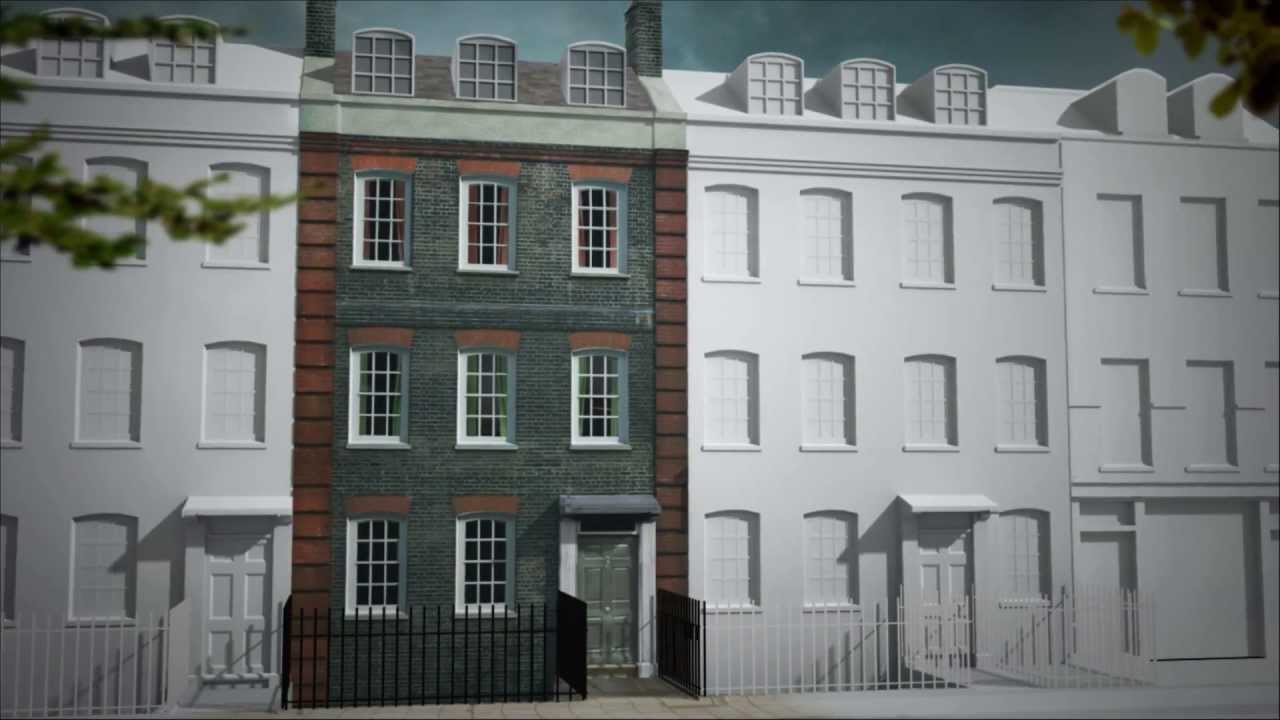

information on the Chapel Royal, see this article by Carolyn Harris. - [TH], the Palace Gardensgardensgardens Source: Jan Kip, plan of St.James's Palace and Gardens, early 18th centuryThe

palace gardens at St. James's Palace, which was the primary royal residence until

early nineteenth century, are pictured in the bird's eye plan by Jan Kip shown

here (via Wikimedia Commons). Something of the spirit of the parks and gardens of

the period can be grasped by examining the 1745 painting of St. James's Park and the Mall, by Joseph Nickolls,

discussed here. - [TH], Drawing-Room, Operaoperaopera

Source: Jan Kip, plan of St.James's Palace and Gardens, early 18th centuryThe

palace gardens at St. James's Palace, which was the primary royal residence until

early nineteenth century, are pictured in the bird's eye plan by Jan Kip shown

here (via Wikimedia Commons). Something of the spirit of the parks and gardens of

the period can be grasped by examining the 1745 painting of St. James's Park and the Mall, by Joseph Nickolls,

discussed here. - [TH], Drawing-Room, Operaoperaopera Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatreOpera became

extraordinarily fashionable during the eighteenth century. Read more about the

history of opera during the period from the

Victoria and Albert Museum. The image included here shows a riot during

an opera at Covent Garden Theatre in 1763. - [TH], or Play, the Haughty

Awe-Inspiring Lady – A thousand Times has he stood amaz'd at the prodigious Likeness

between his little Mistress, and this Court Beauty; but was still as far from

imagining they were the same, as he was the first Hour he had accosted her in the

Playhouse, though it is not impossible, but that her Resemblance to this celebrated

Lady, might keep his Inclination alive something longer than otherwise they would

have been; and that it was to the Thoughts of this (as he supposed) unenjoy'd

Charmer, she ow'd in great measure the Vigour of his latter Caresses.

Source: Engraving depicting a riot at Covent Garden TheatreOpera became

extraordinarily fashionable during the eighteenth century. Read more about the

history of opera during the period from the

Victoria and Albert Museum. The image included here shows a riot during

an opera at Covent Garden Theatre in 1763. - [TH], or Play, the Haughty

Awe-Inspiring Lady – A thousand Times has he stood amaz'd at the prodigious Likeness

between his little Mistress, and this Court Beauty; but was still as far from

imagining they were the same, as he was the first Hour he had accosted her in the

Playhouse, though it is not impossible, but that her Resemblance to this celebrated

Lady, might keep his Inclination alive something longer than otherwise they would

have been; and that it was to the Thoughts of this (as he supposed) unenjoy'd

Charmer, she ow'd in great measure the Vigour of his latter Caresses.

BUT he varied not so much from his Sex as to be able to prolong Desire, to any great Length after Possession: The rifled Charms of Fantomina soon lost their PoinancypoignancypoignancyAccording to the OED, "poingnancy" refers to the sharpness or piquancy of a feeling. - [TH], and grew tastless and insipid; and when the Season of the Year inviting the Company to the Bath, she offer'd to accompany him, he made an Excuse to go without her. She easily perceiv'd his Coldness, and the Reason why he pretended her going would be inconvenient, and endur'd as much from the Discovery as any of her Sex could do: She dissembleddissembledissembleTo "dissemble" is to disguise or feign--to appear otherwise (OED). - [TH] it, however, before him, and took her Leave of him with the Shew of no other Concern than his Absence occasion'd: But this she did to take from him all Suspicion of her following him, as she intended, and had already laid a Scheme for. – From her first finding out that he design'd to leave her behind, she plainly saw it was for no other Reason, than being tir'd of her Conversation, he was willing to be at liberty to pursue new Conquests; and wisely considering that Complaints, Tears, Swooning, and all the Extravagancies which Women make use of in such Cases, have little Prevailence over a Heart inclin'd to rove, and only serve to render those who practice them more contemptible, by robbing them of that Beauty which alone can bring back the 268 fugitive Lover, she resolved to take another Course; and remembring the Height of Transport she enjoyed when the agreeable Beauplaisir kneel'd at her Feet, imploring her first Favours, she long'd to prove the same again. Not but a Woman of her Beauty and Accomplishments might have beheld a Thousand in that Condition Beauplaisir had been; but with her Sex's Modesty, she had not also thrown off another Virtue equally valuable, tho' generally unfortunate, Constancy: She loved Beauplaisir; it was only he whose Solicitations could give her Pleasure; and had she seen the whole Species despairing, dying for her sake, it might, perhaps, have been a Satisfaction to her Pride, but none to her more tender Inclination. – Her Design was once more to engage him, to hear him sigh, to see him languish, to feel the strenuous Pressures of his eager Arms, to be compelled, to be sweetly forc'd to what she wished with equal Ardour, was what she wanted, and what she had form'd a Stratagem to obtain, in which she promis'd herself Success.

SHE no sooner heard he had left the Town, than making a Pretence to her Aunt, that

she was going to visit a Relation in the Country, went towards BathbathbathBath is a fashionable resort and thermal spa town located in

the south west of England, near Bristol. In the eighteenth century, it became a

destination and, according to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, "one of the most beautiful cities

in Europe, with architecture and landscape combined harmoniously for the

enjoyment of the spa town’s cure takers." - [TH], attended but by two

Servants, who she found Reasons to quarrel with on the Road and discharg'd: Clothing

herself in a Habit she had brought with her, she forsook the Coach, and went into a

WagonwagonwagonA wagon is a much ruder

form of transportation than the elegant coach, befitting Fantomina's new

character. Travel by stage coach from London to Bath during this period would have

taken at least two days. - [TH], in which Equipage she arriv'd at Bath. The Dress

she was in, was a round-ear'd Capcapcap Source: Round-eared cap (VAM)According to The

Dictionary of Fashion History, a round-eared cap is a "white

indoor cap curving round the face to the level of the ears or below," often

ruffled, and drawn close with a string along the shallow back edge of the cap.

These caps were popular among all classes from around 1730 to 1760, making this an

early reference. The image included here, from the Victoria and Albert Museum, shows a mannequin in a quilted green

petticoat and round-eared cap. - [TH], a short Red Petticoat, and a

little Jacket of Grey Stuffstuffstuff"Stuff" here

refers to a type of woven material made of worsted woollen cloth. See OED sense

5c. - [TH]; all the rest of her Accoutrements were answerable to these, and join'd

with a broad Country Dialect, a rude unpolish'd Air, which she, having been bred in

these Parts, knew very well how to imitate, with her Hair and Eye-brows black'd, made

it impossible for her to be known, or taken for any other than what she seem'd. Thus

disguis'd did she offer herself to Service in the House where Beauplaisir lodg'd,

having made it her Business to find out immediately where he was. Notwithstanding

this Metamorphosis 269 she was still extremely

pretty; and the Mistress of the House happening at that Time to want a MaidmaidmaidA maidservant was one of the lowest-paid

members of a domestic household, though others--like scullery maids, who were

responsible for scrubbing kitchen pans--earned much less. A housemaid was

typically responsible for airing rooms, emptying chamber pots, cleaning and

beating rugs and beds, and so on. For more information on female domestic

servants, see Part 12

of Eighteenth-Century Women: An Anthology, Volume

21. - [TH], was very glad of the Opportunity of taking her. She was

presently receiv'd into the Family; and had a Post in it (such as she would have

chose, had she been left at her Liberty,) that of making the Gentlemen's Beds,

getting them their Breakfasts, and waiting on them in their Chambers. Fortune in this

Exploit was extremely on her side; there were no others of the Male-Sex in the House,

than an old Gentleman, who had lost the Use of his Limbs with the Rheumatism, and had

come thither for the Benefit of the

Waterswaterswaters

Source: Round-eared cap (VAM)According to The

Dictionary of Fashion History, a round-eared cap is a "white

indoor cap curving round the face to the level of the ears or below," often

ruffled, and drawn close with a string along the shallow back edge of the cap.

These caps were popular among all classes from around 1730 to 1760, making this an

early reference. The image included here, from the Victoria and Albert Museum, shows a mannequin in a quilted green

petticoat and round-eared cap. - [TH], a short Red Petticoat, and a

little Jacket of Grey Stuffstuffstuff"Stuff" here

refers to a type of woven material made of worsted woollen cloth. See OED sense

5c. - [TH]; all the rest of her Accoutrements were answerable to these, and join'd

with a broad Country Dialect, a rude unpolish'd Air, which she, having been bred in

these Parts, knew very well how to imitate, with her Hair and Eye-brows black'd, made

it impossible for her to be known, or taken for any other than what she seem'd. Thus

disguis'd did she offer herself to Service in the House where Beauplaisir lodg'd,

having made it her Business to find out immediately where he was. Notwithstanding

this Metamorphosis 269 she was still extremely

pretty; and the Mistress of the House happening at that Time to want a MaidmaidmaidA maidservant was one of the lowest-paid

members of a domestic household, though others--like scullery maids, who were

responsible for scrubbing kitchen pans--earned much less. A housemaid was

typically responsible for airing rooms, emptying chamber pots, cleaning and

beating rugs and beds, and so on. For more information on female domestic

servants, see Part 12

of Eighteenth-Century Women: An Anthology, Volume

21. - [TH], was very glad of the Opportunity of taking her. She was

presently receiv'd into the Family; and had a Post in it (such as she would have

chose, had she been left at her Liberty,) that of making the Gentlemen's Beds,

getting them their Breakfasts, and waiting on them in their Chambers. Fortune in this

Exploit was extremely on her side; there were no others of the Male-Sex in the House,

than an old Gentleman, who had lost the Use of his Limbs with the Rheumatism, and had

come thither for the Benefit of the

Waterswaterswaters Source: Rowlandson, 'The Comforts of Bath' (1798)Througout the

eighteenth century, Bath--known for its thermal springs--became a fashionable

place to relax and "take the waters." Thomas Rowlandson's satirical 1798 watercolor, "The Comforts of Bath: The Pump

Room," included here via Wikimedia Commons, depicts patients suffering

from a variety of illnesses descending on the Pump Room to drink the hot mineral

spring waters. It was believed that the mineral spring waters had curative

properties, though many people went to Bath for relaxation and leisure in

general. - [TH], and her belov'd Beauplaisir; so that she was in no Apprehensions

of any Amorous Violence, but where she wish'd to find it. Nor were her Designs

disappointed: He was fir'd with the first Sight of her; and tho' he did not presently

take any farther Notice of her, than giving her two or three hearty Kisses, yet she,

who now understood that Language but too well, easily saw they were the Prelude to

more substantial Joys. – Coming the next Morning to bring his Chocolate, as he had

order'd, he catch'd her by the pretty Leg, which the Shortness of her Petticoat did

not in the least oppose; then pulling her gently to him, ask'd her, how long

she had been at Service? – How many Sweethearts she had? If she had ever been in

Love? and many other such Questions, befitting one of the Degree she

appear'd to be: All which she answer'd with such seeming Innocence, as more enflam'd

the amorous Heart of him who talk'd to her. He compelled her to sit in his Lap; and

gazing on her blushing Beauties, which, if possible, receiv'd Addition from her plain

and rural Dress, he soon lost the Power of containing himself. – His wild Desires

burst out in all his Words and Actions: he call'd her little Angel, Cherubim, swore

he must enjoy her, though Death were to be the Consequence, devour'd her Lips, her

Breasts with greedy Kisses, held to his burning Bosom her half-yielding,

half-reluctant Body, nor suffered her to get loose, 270 till he had ravaged all, and glutted each rapacious

Sense with the sweet Beauties of the pretty CeliaceliaceliaCelia is a generic pastoral female name. - [TH], for that

was the Name she bore in this second Expedition. – Generous as Liberality itself to

all who gave him Joy this way, he gave her a handsome Sum of Gold, which she durst

not now refuse, for fear of creating some Mistrust, and losing the Heart she so

lately had regain'd; therefore taking it with an humble Curtesy, and a well

counterfeited Shew of Surprise and Joy, cry'd, O Law, Sir! what must I do for

all this? He laughed at her Simplicity, and kissing her again, tho' less

fervently than he had done before, bad her not be out of the Way when he came home at

Night. She promis'd she would not, and very obediently kept her Word.

Source: Rowlandson, 'The Comforts of Bath' (1798)Througout the

eighteenth century, Bath--known for its thermal springs--became a fashionable

place to relax and "take the waters." Thomas Rowlandson's satirical 1798 watercolor, "The Comforts of Bath: The Pump

Room," included here via Wikimedia Commons, depicts patients suffering

from a variety of illnesses descending on the Pump Room to drink the hot mineral

spring waters. It was believed that the mineral spring waters had curative

properties, though many people went to Bath for relaxation and leisure in

general. - [TH], and her belov'd Beauplaisir; so that she was in no Apprehensions

of any Amorous Violence, but where she wish'd to find it. Nor were her Designs

disappointed: He was fir'd with the first Sight of her; and tho' he did not presently

take any farther Notice of her, than giving her two or three hearty Kisses, yet she,

who now understood that Language but too well, easily saw they were the Prelude to

more substantial Joys. – Coming the next Morning to bring his Chocolate, as he had

order'd, he catch'd her by the pretty Leg, which the Shortness of her Petticoat did

not in the least oppose; then pulling her gently to him, ask'd her, how long

she had been at Service? – How many Sweethearts she had? If she had ever been in

Love? and many other such Questions, befitting one of the Degree she

appear'd to be: All which she answer'd with such seeming Innocence, as more enflam'd

the amorous Heart of him who talk'd to her. He compelled her to sit in his Lap; and

gazing on her blushing Beauties, which, if possible, receiv'd Addition from her plain

and rural Dress, he soon lost the Power of containing himself. – His wild Desires

burst out in all his Words and Actions: he call'd her little Angel, Cherubim, swore

he must enjoy her, though Death were to be the Consequence, devour'd her Lips, her

Breasts with greedy Kisses, held to his burning Bosom her half-yielding,

half-reluctant Body, nor suffered her to get loose, 270 till he had ravaged all, and glutted each rapacious

Sense with the sweet Beauties of the pretty CeliaceliaceliaCelia is a generic pastoral female name. - [TH], for that

was the Name she bore in this second Expedition. – Generous as Liberality itself to

all who gave him Joy this way, he gave her a handsome Sum of Gold, which she durst

not now refuse, for fear of creating some Mistrust, and losing the Heart she so

lately had regain'd; therefore taking it with an humble Curtesy, and a well

counterfeited Shew of Surprise and Joy, cry'd, O Law, Sir! what must I do for

all this? He laughed at her Simplicity, and kissing her again, tho' less

fervently than he had done before, bad her not be out of the Way when he came home at

Night. She promis'd she would not, and very obediently kept her Word.

His Stay at Bath exceeded not a Month; but in that Time his suppos'd Country Lass

had persecuted him so much with her Fondness, that in spite of the Eagerness with

which he first enjoy'd her, he was at last grown more weary of her, than he had been

of Fantomina; which she perceiving, would not be troublesome, but quitting her Serviceserviceservice"Service" in this sense

refers to the position of domestic servitude she has acquired (OED). - [TH],

remained privately in the Town till she heard he was on his Return; and in that Time

provided herself of another Disguise to carry on a third Plot, which her inventing

Brain had furnished her with, once more to renew his twice-decay'd Ardours. The Dress

she had order'd to be made, was such as Widows wear in their first Mourningmourning_mourning_ Source: Portrait of a widow in mourning garbIn this enamel miniature portrait c.1710, via Philip

Mould and Company, the artist

Christian Zincke has depicted Henrietta Maria, Lady Ashburnham, in first

mourning for her husband; Henrietta Maria is twenty-three in this

portrait. First or deep mourning lasted approximately three months after

the death of a spouse, during which time the mourner wore non-reflective black

fabrics like bombazine. - [TH], which, together with the most afflicted and

penitential Countenance that ever was seen, was no small Alteration to her who us'd

to seem all Gaiety. – To add to this, her Hair, which she was accustom'd to wear very

loose, both when Fantomina and Celia, was now ty'd back so straight, and her PinnerspinnerspinnersA pinner is, according to

the OED, a cap with long flaps on either side that fits more tightly around the

head; it is often worn by women of higher social standing. "Pinners" also refers

to the flaps on either side of the cap. - [TH] coming so very forward, that there

was none of it to be seen. In fine, her Habit and her Air were so much chang'd, that

she was not more difficult to be known in the rude Country Girl, than she was now in

the sorrowful Widow. 271

Source: Portrait of a widow in mourning garbIn this enamel miniature portrait c.1710, via Philip

Mould and Company, the artist

Christian Zincke has depicted Henrietta Maria, Lady Ashburnham, in first

mourning for her husband; Henrietta Maria is twenty-three in this

portrait. First or deep mourning lasted approximately three months after

the death of a spouse, during which time the mourner wore non-reflective black

fabrics like bombazine. - [TH], which, together with the most afflicted and

penitential Countenance that ever was seen, was no small Alteration to her who us'd

to seem all Gaiety. – To add to this, her Hair, which she was accustom'd to wear very

loose, both when Fantomina and Celia, was now ty'd back so straight, and her PinnerspinnerspinnersA pinner is, according to

the OED, a cap with long flaps on either side that fits more tightly around the

head; it is often worn by women of higher social standing. "Pinners" also refers

to the flaps on either side of the cap. - [TH] coming so very forward, that there

was none of it to be seen. In fine, her Habit and her Air were so much chang'd, that

she was not more difficult to be known in the rude Country Girl, than she was now in

the sorrowful Widow. 271

SHE knew that Beauplaisir came alone in his Chariot to the Bath, and in the Time of her being Servant in the House where he lodg'd, heard nothing of any Body that was to accompany him to London, and hop'd he wou'd return in the same Manner he had gone: She therefore hir'd Horses and a Man to attend her to an Inn about ten Miles on this side Bath, where having discharg'd them, she waited till the Chariot should come by; which when it did, and she saw that he was alone in it, she call'd to him that drove it to stop a Moment, and going to the Door saluted the Master with these Words:

THE Distress'd and Wretched, Sir, (said she,) never fail to excite Compassion in a generous Mind; and I hope I am not deceiv'd in my Opinion that yours is such: – You have the Appearance of a Gentleman, and cannot, when you hear my Story, refuse that Assistance which is in your Power to give to an unhappy Woman, who without it, may be rendered the most miserable of all created Beings.

IT would not be very easy to represent the Surprise, so odd an Address created in the Mind of him to whom it was made. – She had not the Appearance of one who wanted Charity; and what other Favour she requir'd he cou'd not conceive: But telling her, she might command any Thing in his Power, gave her Encouragement to declare herself in this Manner: You may judge, (resumed she,) by the melancholy Garb I am in, that I have lately lost all that ought to be valuable to Womankind; but it is impossible for you to guess the Greatness of my Misfortune, unless you had known my Husband, who was Master of every Perfection to endear him to a Wife's Affections. — But, notwithstanding, I look on myself as the most unhappy of my Sex in out-living him, I must so far obey the Dictates of my Discretion, as to take care of the little Fortune he left behind him, which being in the hands of a Brother of his in London, will be all carried off to Holland, where he is going to settle; if I reach not the Town before 272he leaves it, I am undone for ever. – To which End I left BristolbristolbristolBristol is a port town about 15 miles west of Bath. - [TH], the Place where we liv'd, hoping to get a Place in the Stage at Bath, but they were all taken up before I came; and being, by a Hurt I got in a Fall, render'd incapable of travelling any long Journey on Horseback, I have no Way to go to London, and must be inevitably ruin'd in the Loss of all I have on Earth, without you have good Nature enough to admit me to take Part of your Chariot.

HERE the feigned Widow ended her sorrowful Tale, which had been several Times interrupted by a Parenthesis of Sighs and Groans; and Beauplaisir, with a complaisant and tender Air, assur'd her of his Readiness to serve her in Things of much greater Consequence than what she desir'd of him; and told her, it would be an Impossibility of denying a Place in his Chariot to a Lady, who he could not behold without yielding one in his Heart. She answered the Compliments he made her but with Tears, which seem'd to stream in such abundance from her Eyes, that she could not keep her Handkerchief from her Face one Moment. Being come into the Chariot, Beauplaisir said a thousand handsome Things to perswade her from giving way to so violent a Grief, which, he told her, would not only be distructive to her Beauty, but likewise her Health. But all his Endeavours for Consolement appear'd ineffectual, and he began to think he should have but a dull Journey, in the Company of one who seem'd so obstinately devoted to the Memory of her dead Husband, that there was no getting a Word from her on any other Theme: – But bethinking himself of the celebrated Story of the Ephesian Matronephesian_matronephesian_matronIn the story of the Ephesian matron, first told in Petronius' Satyricon, a new widow in deep mourning for her husband and known for her chastity is seduced by a soldier tasked with guarding the crucified bodies of three theives. While the soldier and the beautiful young widow are otherwise employed, one of the bodies disappears, and to save her lover, the widow replaces the missing thief with her husband's corpse. This story was adapted in the seventeenth century by Jean de La Fontaine. Read more about this story and the seventeenth-century adaptation that Haywood would have known of in Robert Colton's article, "The Story of the Widow of Ephesus in Petronius and La Fontaine." - [TH], it came into his Head to make Tryal, she who seem'd equally susceptible of Sorrow, might not also be so too of Love; and having begun a Discourse on almost every other Topick, and finding her still incapable of answering, resolv'd to put it to the Proof, if this would have no more Effect to rouze her sleeping Spirits: – With a gay Air, therefore, though accompany'd with 273 the greatest Modesty and Respect, he turned the Conversation, as though without Design, on that Joy-giving Passion, and soon discover'd that was indeed the Subject she was best pleas'd to be entertained with; for on his giving her a Hint to begin upon, never any Tongue run more voluble than hers, on the prodigious Power it had to influence the Souls of those posses'd of it, to Actions even the most distant from their Intentions, Principles, or Humours. – From that she pass'd to a Description of the Happiness of mutual Affection; – the unspeakable Extasy of those who meet with equal Ardency; and represented it in Colours so lively, and disclos'd by the Gestures with which her Words were accompany'd, and the Accent of her Voice so true a Feeling of what she said, that Beauplaisir, without being as stupid, as he was really the contrary, could not avoid perceiving there were Seeds of Fire, not yet extinguish'd, in this fair Widow's Soul, which wanted but the kindling Breath of tender Sighs to light into a Blaze. – He now thought himself as fortunate, as some Moments before he had the Reverse; and doubted not, but, that before they parted, he should find a Way to dry the Tears of this lovely Mourner, to the Satisfaction of them both. He did not, however, offer, as he had done to Fantomina and Celia, to urge his Passion directly to her, but by a thousand little softning Artifices, which he well knew how to use, gave her leave to guess he was enamour'd. When they came to the Inn where they were to lie, he declar'd himself somewhat more freely, and perceiving she did not resent it past Forgiveness, grew more encroaching still: – He now took the Liberty of kissing away her Tears, and catching the Sighs as they issued from her Lips; telling her if Grief was infectious, he was resolv'd to have his Share; protesting he would gladly exchange Passions with her, and be content to bear her Load of Sorrow, if she would as willingly ease the Burden of his Love. – She said little in answer to the strenuous Pressures with which at last he 274 ventur'd to enfold her, but not thinking it Decent, for the Character she had assum'd, to yield so suddenly, and unable to deny both his and her own Inclinations, she counterfeited a fainting, and fell motionless upon his Breast. – He had no great Notion that she was in a real Fit, and the Room they supp'd in happening to have a Bed in it, he took her in his Arms and laid her on it, believing, that whatever her Distemper was, that was the most proper Place to convey her to. – He laid himself down by her, and endeavour'd to bring her to herself; and she was too grateful to her kind Physician at her returning Sense, to remove from the Posture he had put her in, without his Leave.

IT may, perhaps, seem strange that Beauplaisir should in such near Intimacies continue still deceiv'd: I knownarratornarratorWhile "Fantomina" appears to be told in the third person omniscient, there is a first-person narrator who interjects at points with her own thoughts, as she does here. - [TH] there are Men who will swear it is an Impossibility, and that no Disguise could hinder them from knowing a Woman they had once enjoy'd. In answer to these Scruples, I can only say, that besides the Alteration which the Change of Dress made in her, she was so admirably skill'd in the Art of feigning, that she had the Power of putting on almost what Face she pleas'd, and knew so exactly how to form her Behaviour to the Character she represented, that all the Comedians at both Playhouses are infinitely short of her Performances: She could vary her very Glances, tune her Voice to Accents the most different imaginable from those in which she spoke when she appear'd herself. – These Aids from Nature, join'd to the Wiles of Art, and the Distance between the Places where the imagin'd Fantomina and Celia were, might very well prevent his having any Thought that they were the same, or that the fair Widow was either of them: It never so much as enter'd his Head, and though he did fancy he observed in the Face of the latter, Features which were not altogether unknown to him, yet he could not recollect when or where he had known them; – and being told by her, that from her Birth, she had 275 never remov'd from Bristol, a Place where he never was, he rejected the Belief of having seen her, and suppos'd his Mind had been deluded by an Idea of some other, whom she might have a Resemblance of.

THEY pass'd the Time of their Journey in as much Happiness as the most luxurious Gratification of wild Desires could make them; and when they came to the End of it, parted not without a mutual Promise of seeing each other often. – He told her to what Place she should direct a Letter to him; and she assur'd him she would send to let him know where to come to her, as soon as she was fixed in Lodgings.

SHE kept her Promise; and charm'd with the Continuance of his eager Fondness, went not home, but into private Lodgings, whence she wrote to him to visit her the first Opportunity, and enquire for the Widow Bloomer. – She had no sooner dispatched this BilletbilletbilletA "billet" is the French word for letter; a billet doux is a love letter. - [TH], than she repair'd to the House where she had lodg'd as Fantomina, charging the People if Beauplaisir should come there, not to let him know she had been out of Town. From thence she wrote to him, in a different Handhandhand"Hand" here refers to the style of handwriting used in the letter. - [TH], a long Letter of Complaint, that he had been so cruel in not sending one Letter to her all the Time he had been absent, entreated to see him, and concluded with subscribing herself his unalterably Affectionate Fantomina. She received in one Day Answers to both these. The first contain'd these Lines:

To the Charming Mrs. BLOOMER,IT would be impossible, my Angel! for me to express the thousandth Part of that Infinity of Transport, the Sight of your dear Letter gave me. – Never was Woman form'd to charm like you: Never did any look like you, – write like you, – bless like you; – nor did ever Man adore as I do. – Since 276 Yesterday we parted, I have seem'd a Body without a Soul; and had you not by this inspiring Billet, gave me new Life, I know not what by To-morrow I should have been. – I will be with you this Evening about Five: – O, 'tis an Age till then! – But the cursed Formalities of Duty oblige me to Dine with my Lord – who never rises from Table till that Hour; – therefore Adieu till then sweet lovely Mistress of the Soul and all the Faculties of

Your most faithful,BEAUPLAISIR.

The other was in this Manner:

To the Lovely FANTOMINA.IF you were half so sensible as you ought of your own Power of charming, you would be assur'd, that to be unfaithful or unkind to you, would be among the Things that are in their very Natures Impossibilities. – It was my Misfortune, not my Fault, that you were not persecuted every Post with a Declaration of my unchanging Passion; but I had unluckily forgot the Name of the Woman at whose House you are, and knew not how to form a Direction that it might come safe to your Hands. – And, indeed, the Reflection how you might misconstrue my Silence, brought me to Town some Weeks sooner than I intended – If you knew how I have languish'd to renew those Blessings I am permitted to enjoy in your Society, you would rather pity than condemn