"Saturday. The Small-Pox"

By

Mary Wortley Montagu, Lady

Correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Workshop participants at the Behn/Burney

Conference 2019, Laura Runge, Mona Narain, Shea Stuart, Emily MN Kugler

[TP]

SIX

TOWN ECLOGUES

With some other

POEMS

By the Rt. Hon. L. M. W. M.montagu

montagu Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, born

Pierrepont (1689-1762), was an eccentric woman and talented writer who has not

received as much attention as her friends and contemporaries, like Alexander Pope,

with whom she had a close relationship before it turned acrimonious. Montagu was a

member of the aristocracy, daughter of the Earl of Kingston and Lady Mary Fielding

(yes, she was related to the Henry Fielding of Tom Jones

fame!). She fled an arranged marriage and eloped with Edward Wortley Montagu. Most

remember her as a letter-writer, whose letters were designed for posthumous

publication. Most significant in these letters are those typically referred to as

the "Turkish Embassy" letters, because they discuss her experience traveling to

and living in Contantinople (now Istanbul) with her husband, who served as

ambassador to Turkey from 1716-1718.

Her "Town Eclogues," from which this

selection is taken, are a series of six adaptations of the Roman poet Virgil’s

Eclogues, written in 37BCE. An "eclogue" is a kind of poem that presents a snippet

(or a "selection") of life. In Virgil’s eclogues—a series of 10 poems—rural

herdsman sing and discuss their experiences, often relating to the turbulent time

in Rome just as the Roman Empire was emerging. In the early 18th century,

"Augustan" British poets saw themselves as modern inheritors of a Roman tradition

inaugurated by Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome.

Montagu’s eclogues focus

similarly on a turbulent, transitional era characterized by the social, political,

and economic structures of rapid commercialization in the England and the United

Kingdom. These "Town Eclogues" offer a series of six poems, which you can read in

their entirety on Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive. The poems are organized by days of

the week and discuss themes of sexuality, relationships between men and women,

illness, and fashionable society. In this poem, "Saturday; or the Small-Pox," the

poetic speaker recounts the character Flavia’s thoughts about her smallpox scars,

which were shared by Mary Wortley Montagu herself—Montagu suffered from smallpox

in her youth, which marked her for the rest of her life. During her travels to

Turkey, she witnessed the act of inoculation for smallpox, which she employed to

inoculate her children. She brought word of the innovation back to England, though

she is not credited with its popularization. To read more about Montagu’s

connection with the smallpox vaccine, read Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation.

In

1736, Montagu fell in love with an Italian writer, and she left her husband and

family to live with him on the Continent, under cover of traveling for health

reasons. He never caught up with her in Italy, however, and she traveled through

France and Italy in the 40s and 50s, living for a decade with an Italian Count.

After her husband died in 1761, she returned to London, and died of cancer shortly

after. Her letters were published in 1763, but the first complete modern edition

was published in the 1960s. The portrait of Montagu included here was painted in

1725 by Jonathan Richardson. It is currently in the collection of the Earl of

Harrowby, Stafford (via Wikimedia Commons). - [TH]

LONDON:

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, born

Pierrepont (1689-1762), was an eccentric woman and talented writer who has not

received as much attention as her friends and contemporaries, like Alexander Pope,

with whom she had a close relationship before it turned acrimonious. Montagu was a

member of the aristocracy, daughter of the Earl of Kingston and Lady Mary Fielding

(yes, she was related to the Henry Fielding of Tom Jones

fame!). She fled an arranged marriage and eloped with Edward Wortley Montagu. Most

remember her as a letter-writer, whose letters were designed for posthumous

publication. Most significant in these letters are those typically referred to as

the "Turkish Embassy" letters, because they discuss her experience traveling to

and living in Contantinople (now Istanbul) with her husband, who served as

ambassador to Turkey from 1716-1718.

Her "Town Eclogues," from which this

selection is taken, are a series of six adaptations of the Roman poet Virgil’s

Eclogues, written in 37BCE. An "eclogue" is a kind of poem that presents a snippet

(or a "selection") of life. In Virgil’s eclogues—a series of 10 poems—rural

herdsman sing and discuss their experiences, often relating to the turbulent time

in Rome just as the Roman Empire was emerging. In the early 18th century,

"Augustan" British poets saw themselves as modern inheritors of a Roman tradition

inaugurated by Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome.

Montagu’s eclogues focus

similarly on a turbulent, transitional era characterized by the social, political,

and economic structures of rapid commercialization in the England and the United

Kingdom. These "Town Eclogues" offer a series of six poems, which you can read in

their entirety on Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive. The poems are organized by days of

the week and discuss themes of sexuality, relationships between men and women,

illness, and fashionable society. In this poem, "Saturday; or the Small-Pox," the

poetic speaker recounts the character Flavia’s thoughts about her smallpox scars,

which were shared by Mary Wortley Montagu herself—Montagu suffered from smallpox

in her youth, which marked her for the rest of her life. During her travels to

Turkey, she witnessed the act of inoculation for smallpox, which she employed to

inoculate her children. She brought word of the innovation back to England, though

she is not credited with its popularization. To read more about Montagu’s

connection with the smallpox vaccine, read Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation.

In

1736, Montagu fell in love with an Italian writer, and she left her husband and

family to live with him on the Continent, under cover of traveling for health

reasons. He never caught up with her in Italy, however, and she traveled through

France and Italy in the 40s and 50s, living for a decade with an Italian Count.

After her husband died in 1761, she returned to London, and died of cancer shortly

after. Her letters were published in 1763, but the first complete modern edition

was published in the 1960s. The portrait of Montagu included here was painted in

1725 by Jonathan Richardson. It is currently in the collection of the Earl of

Harrowby, Stafford (via Wikimedia Commons). - [TH]

LONDON:

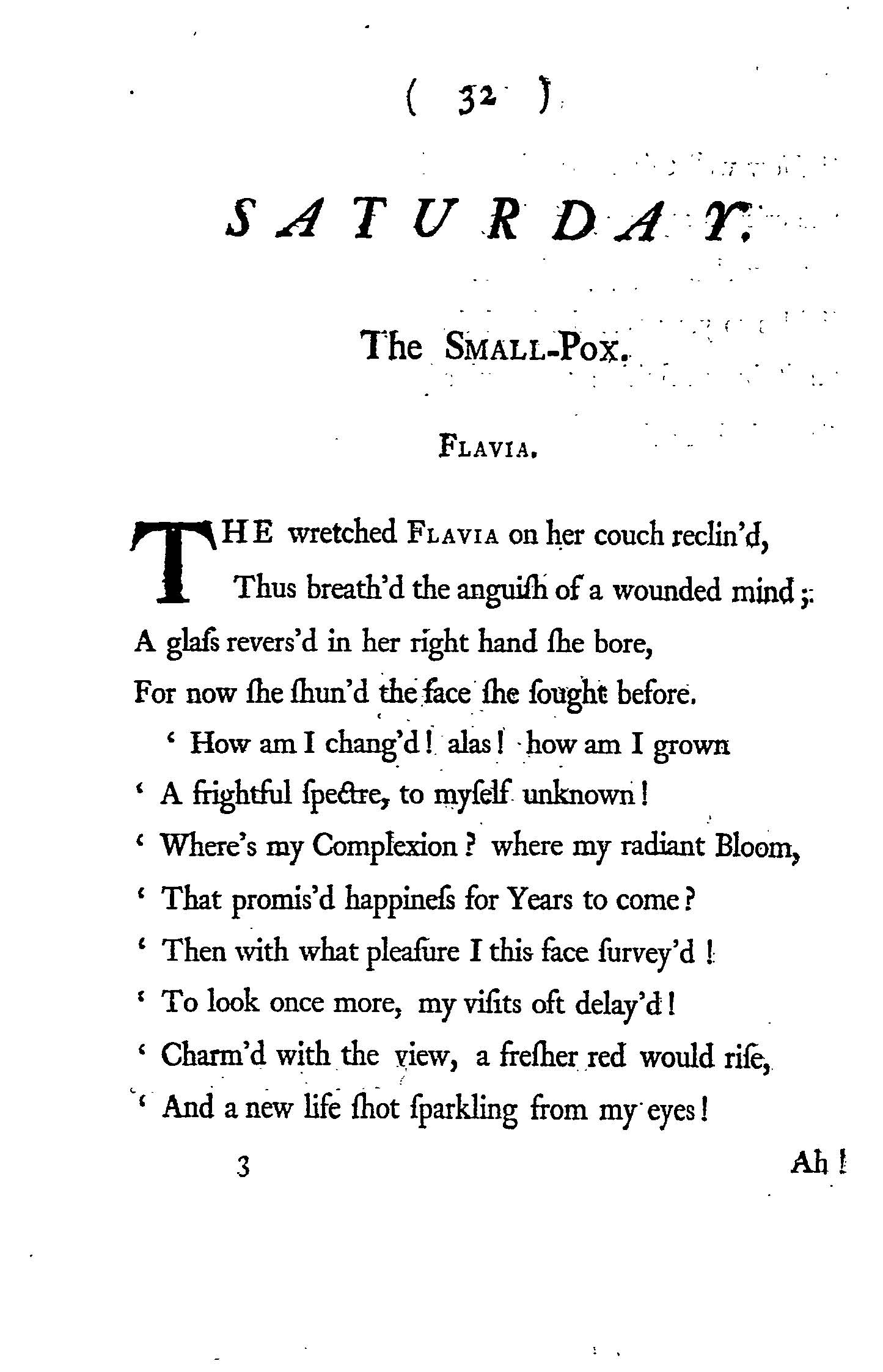

Printed for M. Cooper in Pater-noster-Row. 1747. 32 SATURDAY.

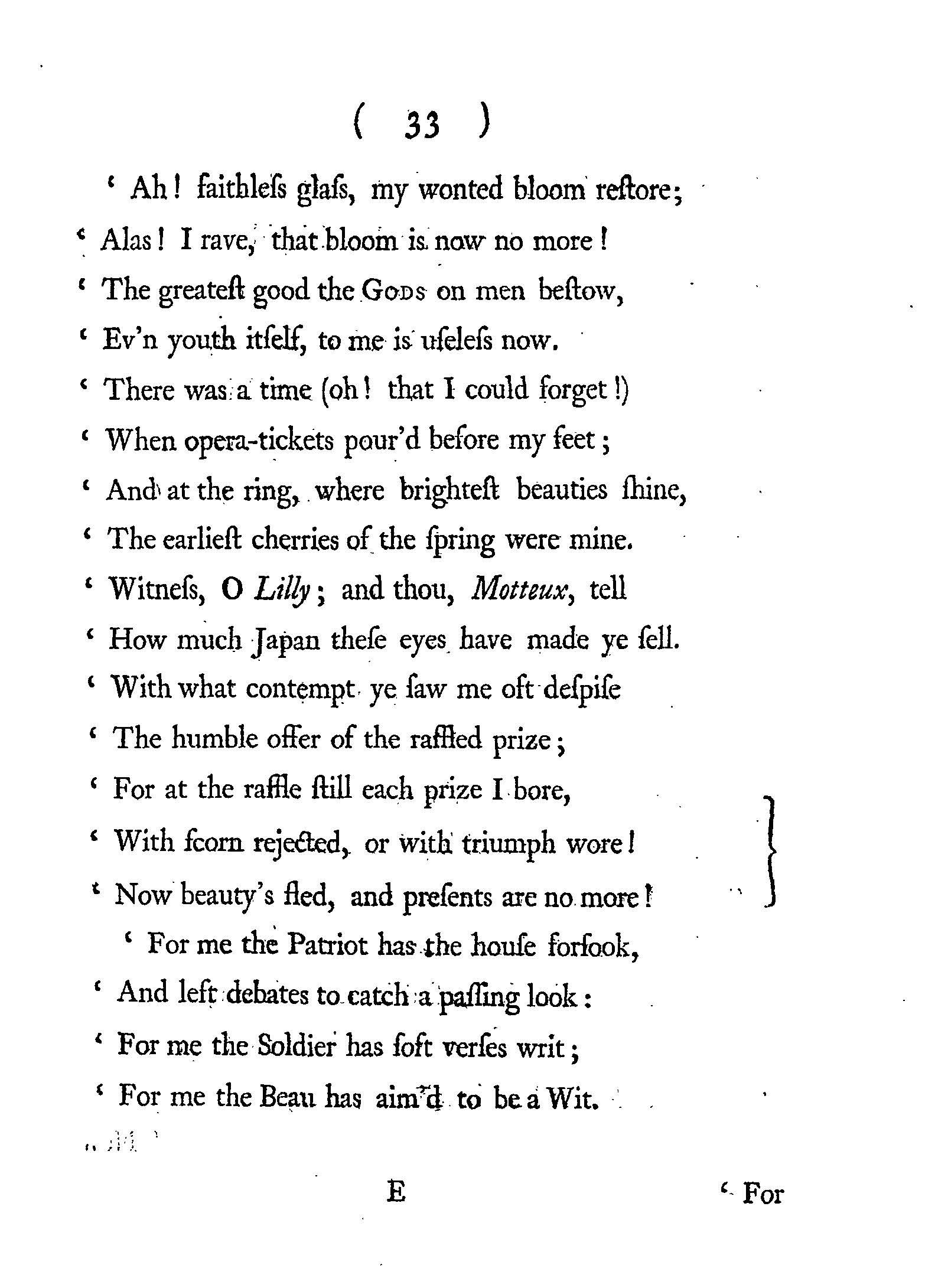

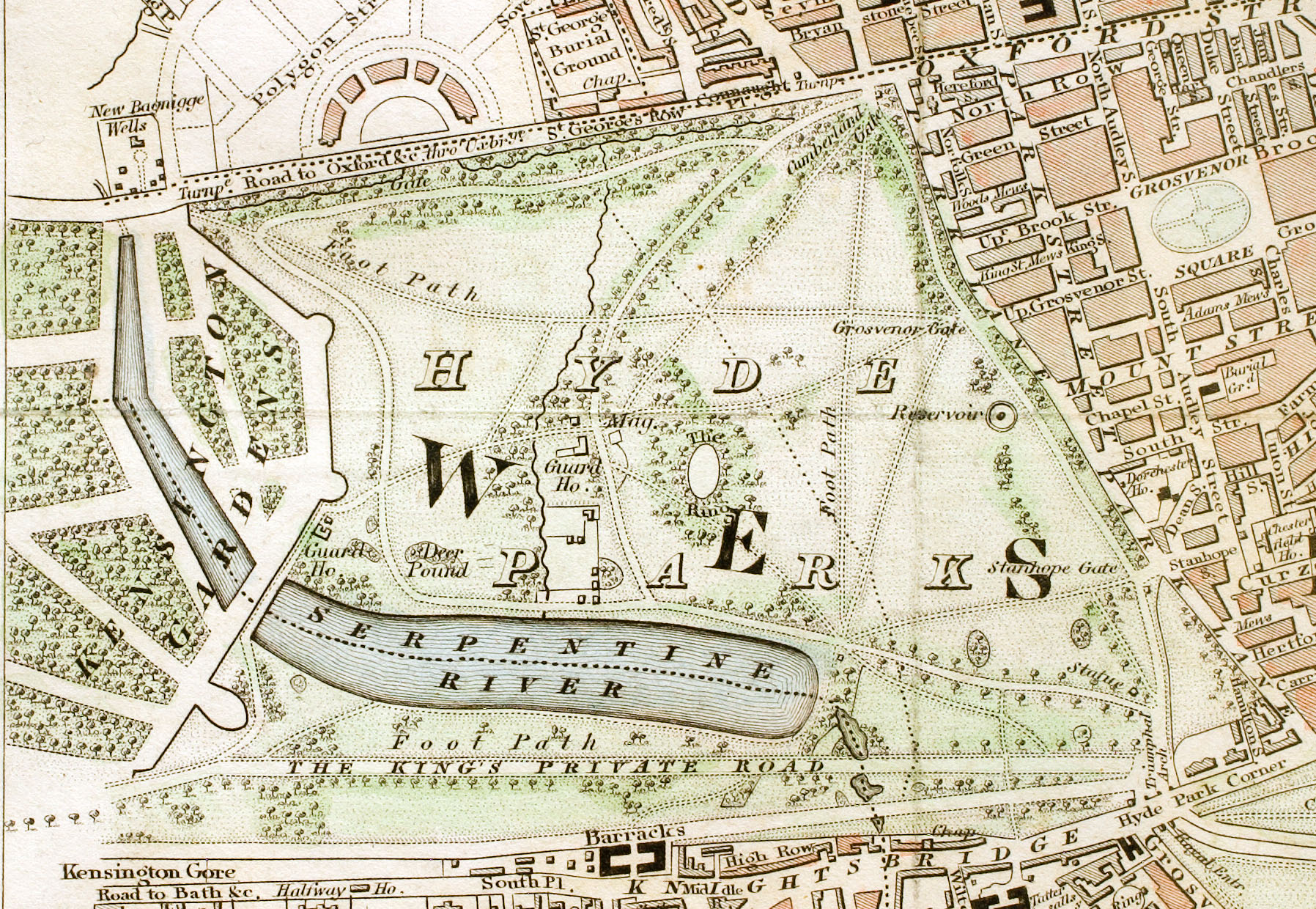

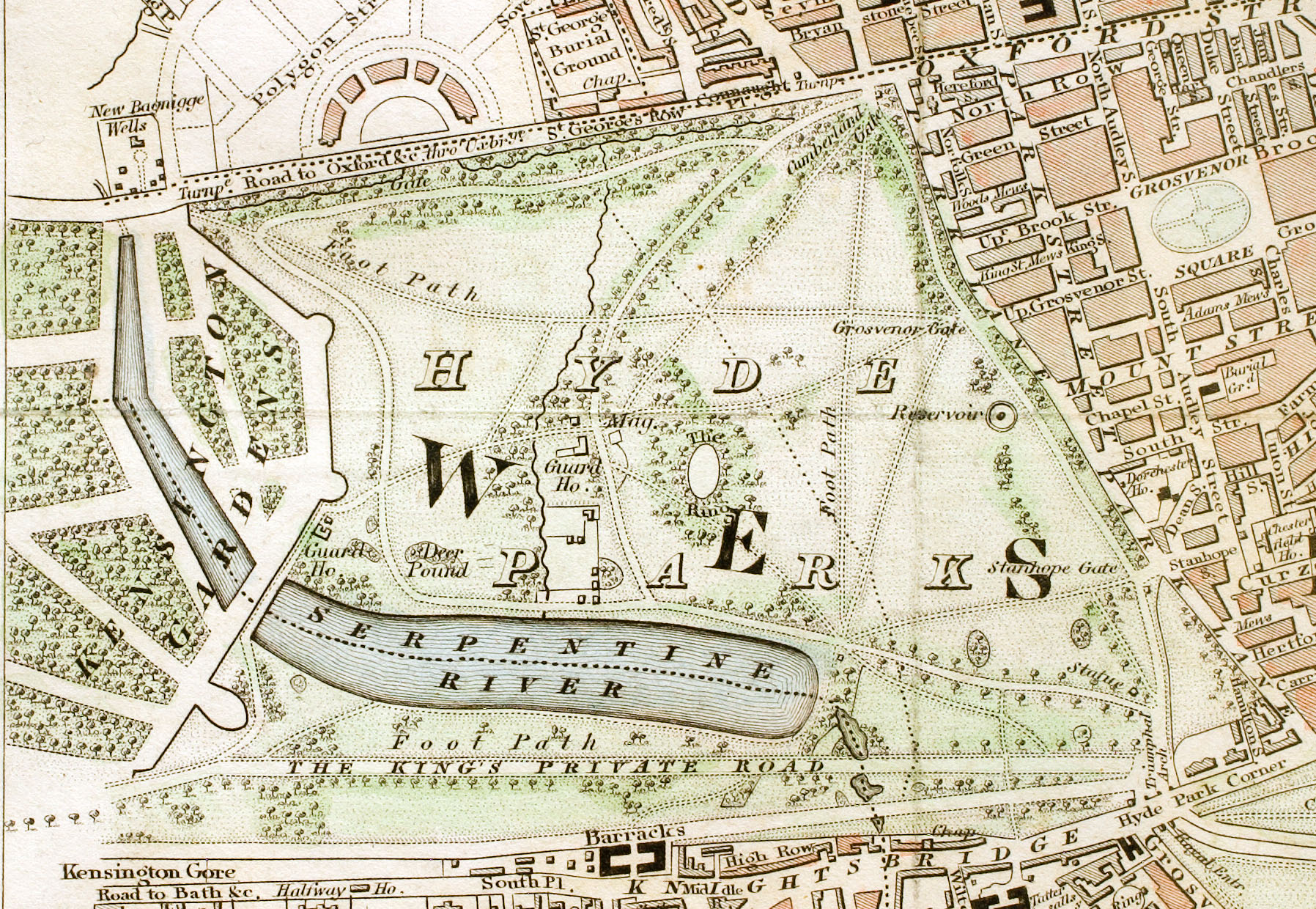

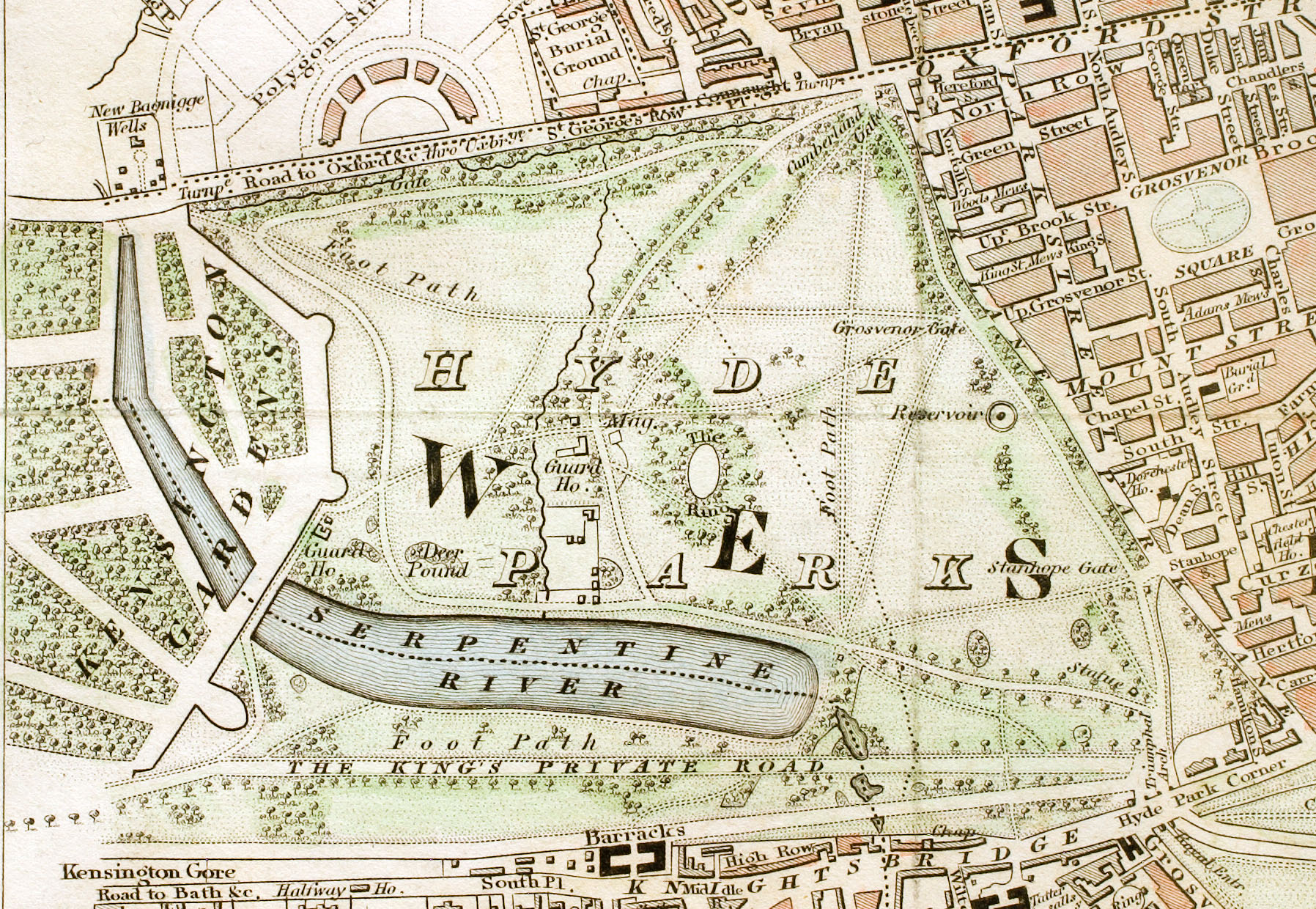

The SMALL-POXsmallpox. smallpoxSmallpox is an infectious disease caused by the variola virus, which ravaged many parts of the world until its eradication in 1980. Throughout the eighteenth century, over 400,000 people died in Europe from the disease. It is characterized by pus-filled blisters that form on the skin, before hardening and falling off; smallpox often caused severe scarring and even blindness among those who survived. The virus was used as a biological weapon, notably by the British against Native Americans in Pontiac's War of the 1760s. The disease was 90% fatal among the Amerindian population, causing mass destruction. Before a vaccine was developed, the virus was managed through a process of inoculation--also called variolation--whereby a small amount of infected fluid, often from a cow, was introduced to a healthy person's body, causing an immune response. This process of inoculation was practiced in Asia and Africa, before appearing in the Ottoman Empire, where Mary Wortley Montagu witnessed the procedure. To read more, see Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation. - [BehnBurney19] FLAVIA. 1THE wretched FLAVIA on her couch reclin'd, 2Thus breath'd the anguish of a wounded mind; 3A glass revers'd in her right hand she bore, 4For now she shun'd the face she sought before. 5'How am I chang'd! alas! how am I grown 6'A frightful spectre, to myself unknown! 7'Where's my complexion? where my radiant bloom, 8'That promis'd happiness for years to come? 9'Then with what pleasure I this face survey'd! 10'To look once more, my visits oft delay'd! 11'Charm'd with the view, a fresher red would rise, 12'And a new life shot sparkling from my eyes! 33 13'Ah! faithless glass, my wonted bloom restore; 14'Alas! I rave, that bloom is now no more! 15'The greatest good the Gods on men bestow, 16'Ev'n youth itself, to me is useless now. 17'There was a time (oh! that I cou'd forget!) 18'When opera-ticketsopera-tickets pour’d before my feet; opera-ticketsOpera was a fashionable entertainment past-time in the eighteenth century. Opera stars were celebrities, often extravagantly-compensated, and also the subject of some criticism, as Michael Burden describes in "Opera, Excess, and the Discourse of Luxury in Eighteenth-Century England." Here, Flavia claims that "opera-tickets pour'd before [her] feet," which would have been an extravagance, indeed. According to Judith Milhous and Robert Hume, throughout much of the period ticket prices were fixed at 1s 6d or 5s, for pit/boxes or gallery seating, respectively. "A season subscription for fifty nights," they note, "was 15 [guineas]" (79). For more information on eighteenth-century opera, see this overview from the Victoria and Albert Museum. For more information on cost of living in the early eighteenth century, see the discussion of coinage at the Old Bailey Online. - [TH] 19'And at the ringring, where brightest beauties shine, ring The "ring"

referred to a circular path in Hyde Park where fashionable people would walk,

ride, or take a carriage ride. It was a place to be seen. You can see a

rendering of the Ring in the detail, included here, of the 1833 map of London

engraved by William Smollinger. For more information on Hyde Park, see article from

Wikipedia. - [LR]

20'The earliest cherries of the spring were mine.

21'Witness, O

Lilly; and thou, MotteuxLilly, tell

LillyCharles

Lilly, also known as Charles Lille, "opened a perfume shop on The Strand in London in 1708 where he sold ‘snuffs

and perfumes that refresh the brain.’" Peter Motteux, author, also

owned an "India house" on Leadenhall Street that sold oriental goods. For more

information about Motteux and his shop, see Wikipedia

and British History Online. - [LR]

22'How much japanJapan these eyes have

made ye sell.

JapanJapanese

artifacts with painted or vanished design. A fashionable item that would be

found in Motteux's store. For more information, see this

article on East Asian lacquer from the Victoria and Albert

Museum. - [LR]

23'With what contempt ye saw me oft despise

24'The humble offer of the raffled prize;

25'For at the raffle still each prize I bore,

26'With scorn rejected, or with triumph wore!

27'Now beauty's fled, and presents are no more!

28'For me the Patriot has the house forsook,

29'And left debates to catch a passing look:

30'For me the Soldier has soft verses writ;

31'For me the Beaubeau_ has aim'd to be

a wit.

beauFrom the French, a beau is a ladies' man, or a suitor, often very fashionable (OED).

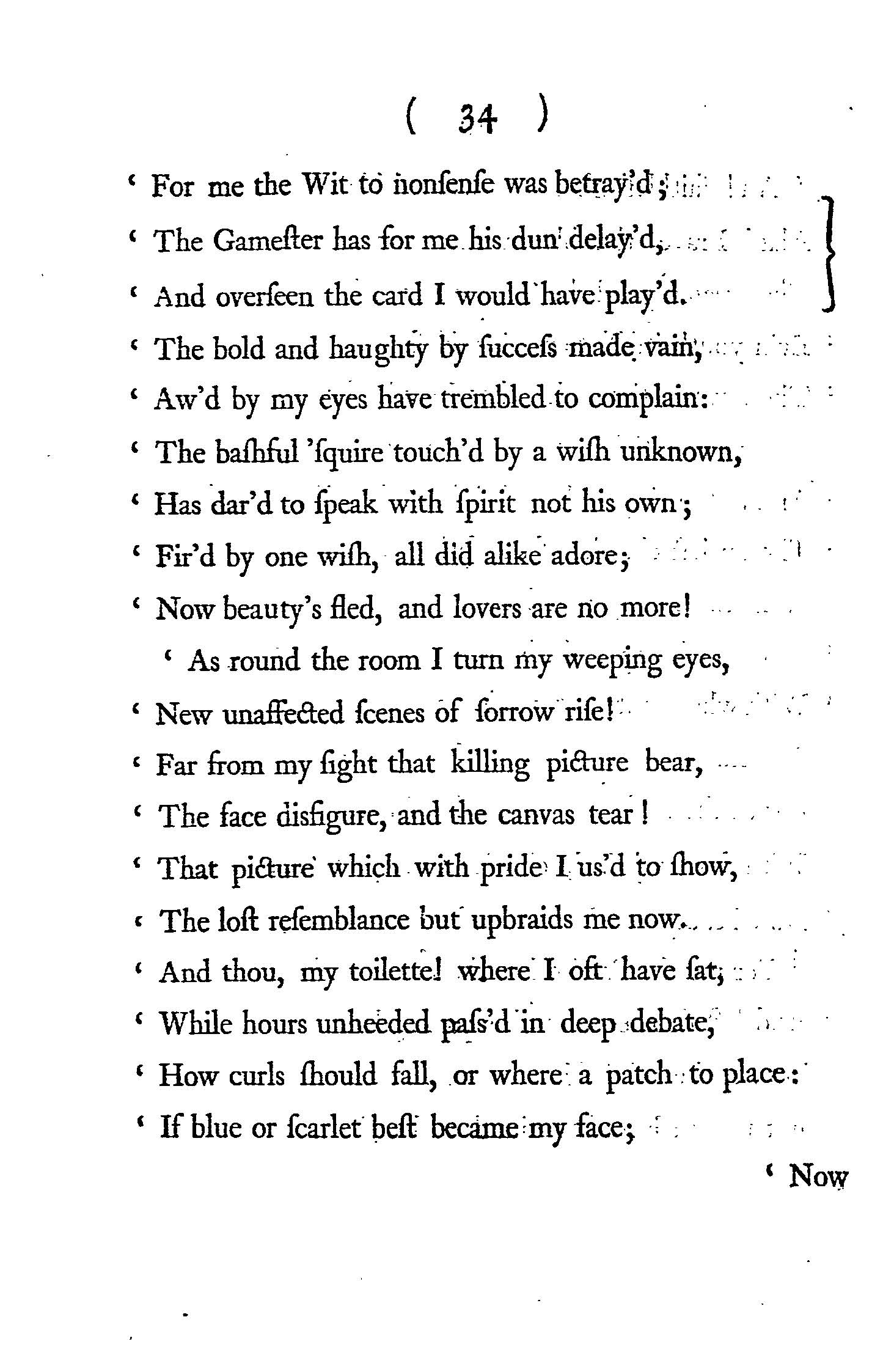

34

32'For me the Witwit to nonsense was

betray'd;

witUsed here as a noun, a wit was (usually) a man known for cleverness or wittiness (OED).

33'The Gamester has for me his dundun

delay'd,

dunUsed here as a noun, a dun in this sense is a demand for payment of a debt (OED). - [BehnBurney19]

34'And overseen the card I would have pay'd.

35'The bold and haughty by success made vain,

36'Aw'd by my eyes, have trembled to complain:

37'The bashful 'Squire touch'd by a wish unknown,

38'Has dar'd to speak with spirit not his own;

39'Fir'd by one wish, all did alike adore;

40'Now beauty's fled, and lovers are no more!

41'As round the room I turn my weeping eyes,

42'New unaffected scenes of sorrow rise!

43'Far from my sight that killing picture bear,

44'The face disfigure, and the canvas tear!

45'That picture, which with pride I us'd to show,

46'The lost resemblance but upbraids me now.

47'And thou, my toilettetoilette! where I

oft have sate,

toiletteFlavia's toilette is her dressing table. The word is used in multiple senses, either to refer to the location of the action of dressing and readying oneself for the day or as a collective term for the items of dressing or applying makeup (OED). - [BehnBurney19]

48'While hours unheeded pass'd in deep debate,

49'How curls should fall, or where a patchpatch to place;

patch

The "ring"

referred to a circular path in Hyde Park where fashionable people would walk,

ride, or take a carriage ride. It was a place to be seen. You can see a

rendering of the Ring in the detail, included here, of the 1833 map of London

engraved by William Smollinger. For more information on Hyde Park, see article from

Wikipedia. - [LR]

20'The earliest cherries of the spring were mine.

21'Witness, O

Lilly; and thou, MotteuxLilly, tell

LillyCharles

Lilly, also known as Charles Lille, "opened a perfume shop on The Strand in London in 1708 where he sold ‘snuffs

and perfumes that refresh the brain.’" Peter Motteux, author, also

owned an "India house" on Leadenhall Street that sold oriental goods. For more

information about Motteux and his shop, see Wikipedia

and British History Online. - [LR]

22'How much japanJapan these eyes have

made ye sell.

JapanJapanese

artifacts with painted or vanished design. A fashionable item that would be

found in Motteux's store. For more information, see this

article on East Asian lacquer from the Victoria and Albert

Museum. - [LR]

23'With what contempt ye saw me oft despise

24'The humble offer of the raffled prize;

25'For at the raffle still each prize I bore,

26'With scorn rejected, or with triumph wore!

27'Now beauty's fled, and presents are no more!

28'For me the Patriot has the house forsook,

29'And left debates to catch a passing look:

30'For me the Soldier has soft verses writ;

31'For me the Beaubeau_ has aim'd to be

a wit.

beauFrom the French, a beau is a ladies' man, or a suitor, often very fashionable (OED).

34

32'For me the Witwit to nonsense was

betray'd;

witUsed here as a noun, a wit was (usually) a man known for cleverness or wittiness (OED).

33'The Gamester has for me his dundun

delay'd,

dunUsed here as a noun, a dun in this sense is a demand for payment of a debt (OED). - [BehnBurney19]

34'And overseen the card I would have pay'd.

35'The bold and haughty by success made vain,

36'Aw'd by my eyes, have trembled to complain:

37'The bashful 'Squire touch'd by a wish unknown,

38'Has dar'd to speak with spirit not his own;

39'Fir'd by one wish, all did alike adore;

40'Now beauty's fled, and lovers are no more!

41'As round the room I turn my weeping eyes,

42'New unaffected scenes of sorrow rise!

43'Far from my sight that killing picture bear,

44'The face disfigure, and the canvas tear!

45'That picture, which with pride I us'd to show,

46'The lost resemblance but upbraids me now.

47'And thou, my toilettetoilette! where I

oft have sate,

toiletteFlavia's toilette is her dressing table. The word is used in multiple senses, either to refer to the location of the action of dressing and readying oneself for the day or as a collective term for the items of dressing or applying makeup (OED). - [BehnBurney19]

48'While hours unheeded pass'd in deep debate,

49'How curls should fall, or where a patchpatch to place;

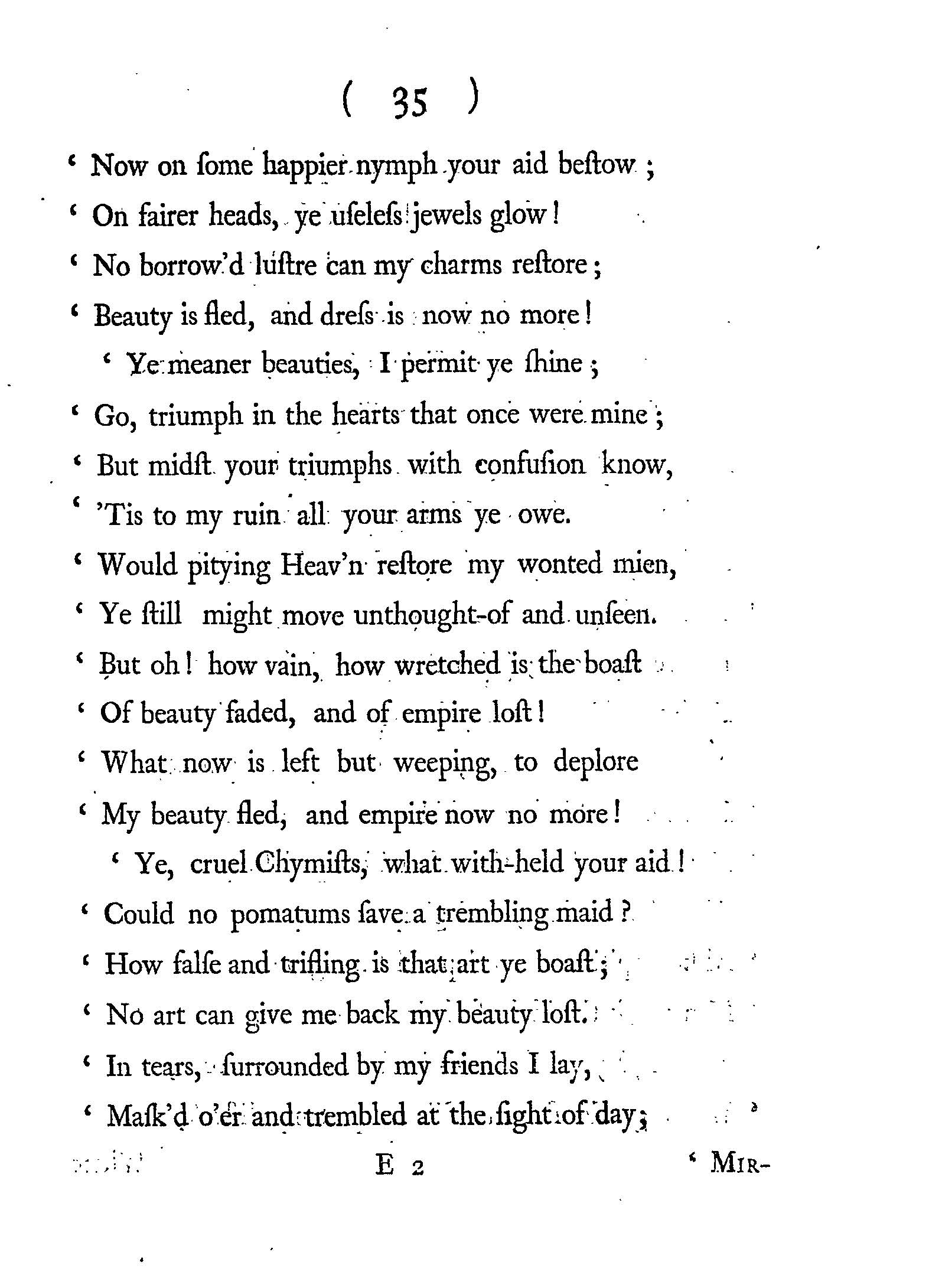

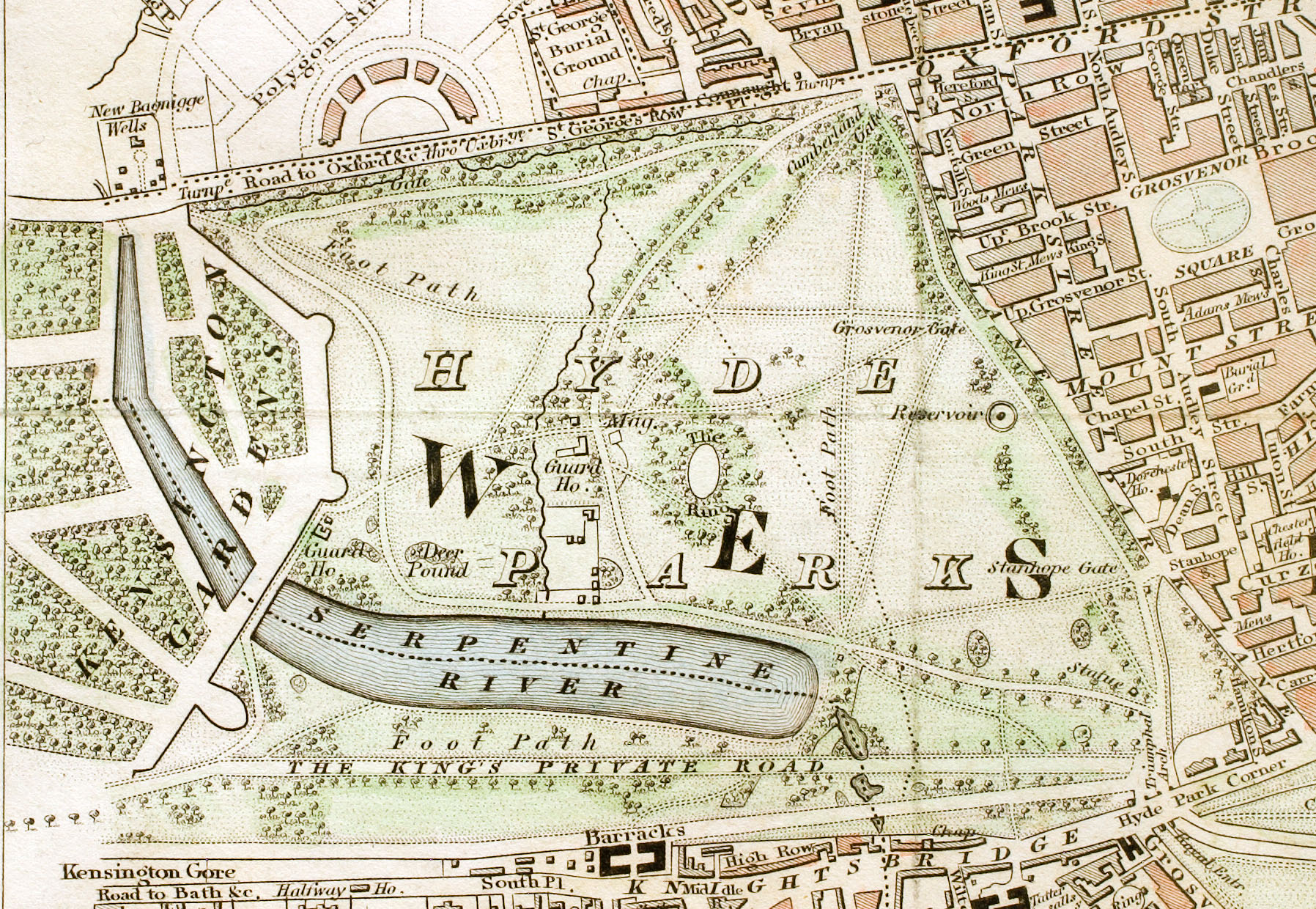

patch A patch in this sense has a specific historical meaning, now obsolete. In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was common for fasionable people to wear "patches," or small pieces of black silk or velvet, sometimes cut into shapes. These patches--called "les mouches" in French, because they resembled a fly--would be worn on the face, sometimes to cover a blemish or simply for fashionable purposes, as an artificial beauty mark. Patches were also sometimes used to declare a particular loyalty or party. To learn more about patches, see the Collector's Weekly article, "That Time the French Aristocracy Was Obsessed With Sexy Face Stickers." The image included here, from that article (via the Metropolitan Museum of Art), is an engraving showing a fashionable young woman at her toilette; she has two patches on her cheek. Engraving “The Morning: The Woman at Her Toilet” by Gilles-Edme Petit, c. 1745-1760. - [TH]

50'If blue or scarlet best became my face;

35

51'Now on some happier nymphnymph your

aid bestow;

nymphAccording to

the OED, "nymph" (n1. 1-3) is a poetic way of describing a beautiful young

woman. It derives from classical mythology, but also can suggest an ironic

usage. - [TH]

52'On fairer heads, ye useless jewels, glow!

53'No borrow'd lusture can my charms restore;

54'Beauty is fled, and dress is now no more!

55'Ye meaner beauties, I permit ye shine;

56'Go, triumph in the hearts that once were mine;

57'But 'midst your triumphs with confusion know,

58''Tis to my ruin all your arms ye owe.

59'Would pitying heav'n restore my wonted mein,

60'Ye still might move unthought-of and unseen:

61'But oh! how vain, how wretched is the boast

62'Of beauty faded, and of empire lost!

63'What now is left but weeping, to deplore

64'My beauty fled, and empire now no more!

65'Ye, cruel Chymists, what with-held your aid!

66'Could no pomatumspomatums save a

trembling maid?

pomatumsPomatum, or pomade, refers to a cosmetic applied to the face--often, it was made with lead, and used to add a whiteness to the skin (OED). - [TH]

67'How false and trifling is that art ye boast;

68'No art can give me back my beauty lost.

69'In tears, surrounded by my friends I lay,

70'Mask'd o'er and trembled at the

sight of day;

36

71'MIRMILIOMirmilio came my fortune to

deplore,

MirmilioIn these

lines, Montagu invokes characters from Samuel Garth's popular early mock-epic

poem, "The Dispensary" (1699). According to Sarah Gillam, writing for the Royal College of Physicians, Mirmillo

likely represents William Gibbons, one of the physicians caught up in the late

17th century dispute about whether to open a free dispensary for the health of

the poor in London. - [TH]

72'(A golden headed cane well carv'd he bore)

73'Cordials, he cried, my spirits must restore:

74'Beauty is fled, and spirit is no more!

75'GALENGalen, the grave;

officious SQUIRTSquirt, was there,

GalenWhile not referenced in Garth's

"Dispensary," Galen is

a Greek physician (129-216 CE) known for pioneering work in anatomy, among

other branches of medicine and philosophy. His humoral work was highly

influential in the Medieval and Early Modern periods.

SquirtAnother

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Squirt--always designated there

"officious"--is an assistant to Horoscope, the chief apothecary in the poem,

who revives his master with a squirt from a urinal at the end of Canto II: Oft he essay'd the Magus to

restore,

By Salt of Succinum's prevailing pow'r;

But still supine the solid Lumber lay,

An Image of scarce animated Clay; Till Fates, indulgent when

Disasters call, Bethought th' Assistant of a Urinal; Whose

Steam the Wight no sooner did receive, But rowz'd, and blest the

Stale Restorative. The Springs of Life their former Vigour feel,

Such Zeal he had for that vile Urensil.

- [TH]

76'With fruitless grief and unavailing care:

77'MACHAONMachaon too, the great MACHAON,

known

MachaonAnother

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Machaon there represents a late

seventeenth-century physician Sir Thomas Millington (Gillum). Machaon is also the name of a mythic figure, the son of the

Greco-Roman god of medicine Asclepius. In The Illiad, Machaon was the surgeon for the Greek army

during the Trojan War. - [TH]

78'By his red cloak and his superior frown;

79 'And why, he cry'd, this grief and this despair?

80'You shall again be well, again be fair;

81'Believe my oath; (with that an oath he swore)

82'False was his oath; my beauty is no more!

83'Cease, hapless maid no more thy tale pursue,

84'Forsake mankind, and bid the world adieu!

85'Monarchs and beauties rule with equal sway;

86'All strive to serve, and glory to obey:

87'Alike unpitied when depos'd they grow;

88'Men mock the idol of their former vow.

89'Adieu! ye parks!—in some obscure recess,

90'Where gentle streams will weep at my distress,

37

91'Where no false friend will in my grief take part,

92'And mourn my ruin with a joyful heart;

93'There let me live in some deserted place,

94'There hide in shades this lost inglorious face.

95'Ye operas, circles, I no more must view!

96'My toilette, patches, all the world adieu!

A patch in this sense has a specific historical meaning, now obsolete. In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was common for fasionable people to wear "patches," or small pieces of black silk or velvet, sometimes cut into shapes. These patches--called "les mouches" in French, because they resembled a fly--would be worn on the face, sometimes to cover a blemish or simply for fashionable purposes, as an artificial beauty mark. Patches were also sometimes used to declare a particular loyalty or party. To learn more about patches, see the Collector's Weekly article, "That Time the French Aristocracy Was Obsessed With Sexy Face Stickers." The image included here, from that article (via the Metropolitan Museum of Art), is an engraving showing a fashionable young woman at her toilette; she has two patches on her cheek. Engraving “The Morning: The Woman at Her Toilet” by Gilles-Edme Petit, c. 1745-1760. - [TH]

50'If blue or scarlet best became my face;

35

51'Now on some happier nymphnymph your

aid bestow;

nymphAccording to

the OED, "nymph" (n1. 1-3) is a poetic way of describing a beautiful young

woman. It derives from classical mythology, but also can suggest an ironic

usage. - [TH]

52'On fairer heads, ye useless jewels, glow!

53'No borrow'd lusture can my charms restore;

54'Beauty is fled, and dress is now no more!

55'Ye meaner beauties, I permit ye shine;

56'Go, triumph in the hearts that once were mine;

57'But 'midst your triumphs with confusion know,

58''Tis to my ruin all your arms ye owe.

59'Would pitying heav'n restore my wonted mein,

60'Ye still might move unthought-of and unseen:

61'But oh! how vain, how wretched is the boast

62'Of beauty faded, and of empire lost!

63'What now is left but weeping, to deplore

64'My beauty fled, and empire now no more!

65'Ye, cruel Chymists, what with-held your aid!

66'Could no pomatumspomatums save a

trembling maid?

pomatumsPomatum, or pomade, refers to a cosmetic applied to the face--often, it was made with lead, and used to add a whiteness to the skin (OED). - [TH]

67'How false and trifling is that art ye boast;

68'No art can give me back my beauty lost.

69'In tears, surrounded by my friends I lay,

70'Mask'd o'er and trembled at the

sight of day;

36

71'MIRMILIOMirmilio came my fortune to

deplore,

MirmilioIn these

lines, Montagu invokes characters from Samuel Garth's popular early mock-epic

poem, "The Dispensary" (1699). According to Sarah Gillam, writing for the Royal College of Physicians, Mirmillo

likely represents William Gibbons, one of the physicians caught up in the late

17th century dispute about whether to open a free dispensary for the health of

the poor in London. - [TH]

72'(A golden headed cane well carv'd he bore)

73'Cordials, he cried, my spirits must restore:

74'Beauty is fled, and spirit is no more!

75'GALENGalen, the grave;

officious SQUIRTSquirt, was there,

GalenWhile not referenced in Garth's

"Dispensary," Galen is

a Greek physician (129-216 CE) known for pioneering work in anatomy, among

other branches of medicine and philosophy. His humoral work was highly

influential in the Medieval and Early Modern periods.

SquirtAnother

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Squirt--always designated there

"officious"--is an assistant to Horoscope, the chief apothecary in the poem,

who revives his master with a squirt from a urinal at the end of Canto II: Oft he essay'd the Magus to

restore,

By Salt of Succinum's prevailing pow'r;

But still supine the solid Lumber lay,

An Image of scarce animated Clay; Till Fates, indulgent when

Disasters call, Bethought th' Assistant of a Urinal; Whose

Steam the Wight no sooner did receive, But rowz'd, and blest the

Stale Restorative. The Springs of Life their former Vigour feel,

Such Zeal he had for that vile Urensil.

- [TH]

76'With fruitless grief and unavailing care:

77'MACHAONMachaon too, the great MACHAON,

known

MachaonAnother

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Machaon there represents a late

seventeenth-century physician Sir Thomas Millington (Gillum). Machaon is also the name of a mythic figure, the son of the

Greco-Roman god of medicine Asclepius. In The Illiad, Machaon was the surgeon for the Greek army

during the Trojan War. - [TH]

78'By his red cloak and his superior frown;

79 'And why, he cry'd, this grief and this despair?

80'You shall again be well, again be fair;

81'Believe my oath; (with that an oath he swore)

82'False was his oath; my beauty is no more!

83'Cease, hapless maid no more thy tale pursue,

84'Forsake mankind, and bid the world adieu!

85'Monarchs and beauties rule with equal sway;

86'All strive to serve, and glory to obey:

87'Alike unpitied when depos'd they grow;

88'Men mock the idol of their former vow.

89'Adieu! ye parks!—in some obscure recess,

90'Where gentle streams will weep at my distress,

37

91'Where no false friend will in my grief take part,

92'And mourn my ruin with a joyful heart;

93'There let me live in some deserted place,

94'There hide in shades this lost inglorious face.

95'Ye operas, circles, I no more must view!

96'My toilette, patches, all the world adieu!

TOWN ECLOGUES

With some other

POEMS

By the Rt. Hon. L. M. W. M.montagu

montagu

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, born

Pierrepont (1689-1762), was an eccentric woman and talented writer who has not

received as much attention as her friends and contemporaries, like Alexander Pope,

with whom she had a close relationship before it turned acrimonious. Montagu was a

member of the aristocracy, daughter of the Earl of Kingston and Lady Mary Fielding

(yes, she was related to the Henry Fielding of Tom Jones

fame!). She fled an arranged marriage and eloped with Edward Wortley Montagu. Most

remember her as a letter-writer, whose letters were designed for posthumous

publication. Most significant in these letters are those typically referred to as

the "Turkish Embassy" letters, because they discuss her experience traveling to

and living in Contantinople (now Istanbul) with her husband, who served as

ambassador to Turkey from 1716-1718.

Her "Town Eclogues," from which this

selection is taken, are a series of six adaptations of the Roman poet Virgil’s

Eclogues, written in 37BCE. An "eclogue" is a kind of poem that presents a snippet

(or a "selection") of life. In Virgil’s eclogues—a series of 10 poems—rural

herdsman sing and discuss their experiences, often relating to the turbulent time

in Rome just as the Roman Empire was emerging. In the early 18th century,

"Augustan" British poets saw themselves as modern inheritors of a Roman tradition

inaugurated by Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome.

Montagu’s eclogues focus

similarly on a turbulent, transitional era characterized by the social, political,

and economic structures of rapid commercialization in the England and the United

Kingdom. These "Town Eclogues" offer a series of six poems, which you can read in

their entirety on Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive. The poems are organized by days of

the week and discuss themes of sexuality, relationships between men and women,

illness, and fashionable society. In this poem, "Saturday; or the Small-Pox," the

poetic speaker recounts the character Flavia’s thoughts about her smallpox scars,

which were shared by Mary Wortley Montagu herself—Montagu suffered from smallpox

in her youth, which marked her for the rest of her life. During her travels to

Turkey, she witnessed the act of inoculation for smallpox, which she employed to

inoculate her children. She brought word of the innovation back to England, though

she is not credited with its popularization. To read more about Montagu’s

connection with the smallpox vaccine, read Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation.

In

1736, Montagu fell in love with an Italian writer, and she left her husband and

family to live with him on the Continent, under cover of traveling for health

reasons. He never caught up with her in Italy, however, and she traveled through

France and Italy in the 40s and 50s, living for a decade with an Italian Count.

After her husband died in 1761, she returned to London, and died of cancer shortly

after. Her letters were published in 1763, but the first complete modern edition

was published in the 1960s. The portrait of Montagu included here was painted in

1725 by Jonathan Richardson. It is currently in the collection of the Earl of

Harrowby, Stafford (via Wikimedia Commons). - [TH]

LONDON:

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, born

Pierrepont (1689-1762), was an eccentric woman and talented writer who has not

received as much attention as her friends and contemporaries, like Alexander Pope,

with whom she had a close relationship before it turned acrimonious. Montagu was a

member of the aristocracy, daughter of the Earl of Kingston and Lady Mary Fielding

(yes, she was related to the Henry Fielding of Tom Jones

fame!). She fled an arranged marriage and eloped with Edward Wortley Montagu. Most

remember her as a letter-writer, whose letters were designed for posthumous

publication. Most significant in these letters are those typically referred to as

the "Turkish Embassy" letters, because they discuss her experience traveling to

and living in Contantinople (now Istanbul) with her husband, who served as

ambassador to Turkey from 1716-1718.

Her "Town Eclogues," from which this

selection is taken, are a series of six adaptations of the Roman poet Virgil’s

Eclogues, written in 37BCE. An "eclogue" is a kind of poem that presents a snippet

(or a "selection") of life. In Virgil’s eclogues—a series of 10 poems—rural

herdsman sing and discuss their experiences, often relating to the turbulent time

in Rome just as the Roman Empire was emerging. In the early 18th century,

"Augustan" British poets saw themselves as modern inheritors of a Roman tradition

inaugurated by Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome.

Montagu’s eclogues focus

similarly on a turbulent, transitional era characterized by the social, political,

and economic structures of rapid commercialization in the England and the United

Kingdom. These "Town Eclogues" offer a series of six poems, which you can read in

their entirety on Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive. The poems are organized by days of

the week and discuss themes of sexuality, relationships between men and women,

illness, and fashionable society. In this poem, "Saturday; or the Small-Pox," the

poetic speaker recounts the character Flavia’s thoughts about her smallpox scars,

which were shared by Mary Wortley Montagu herself—Montagu suffered from smallpox

in her youth, which marked her for the rest of her life. During her travels to

Turkey, she witnessed the act of inoculation for smallpox, which she employed to

inoculate her children. She brought word of the innovation back to England, though

she is not credited with its popularization. To read more about Montagu’s

connection with the smallpox vaccine, read Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation.

In

1736, Montagu fell in love with an Italian writer, and she left her husband and

family to live with him on the Continent, under cover of traveling for health

reasons. He never caught up with her in Italy, however, and she traveled through

France and Italy in the 40s and 50s, living for a decade with an Italian Count.

After her husband died in 1761, she returned to London, and died of cancer shortly

after. Her letters were published in 1763, but the first complete modern edition

was published in the 1960s. The portrait of Montagu included here was painted in

1725 by Jonathan Richardson. It is currently in the collection of the Earl of

Harrowby, Stafford (via Wikimedia Commons). - [TH]

LONDON:Printed for M. Cooper in Pater-noster-Row. 1747. 32 SATURDAY.

The SMALL-POXsmallpox. smallpoxSmallpox is an infectious disease caused by the variola virus, which ravaged many parts of the world until its eradication in 1980. Throughout the eighteenth century, over 400,000 people died in Europe from the disease. It is characterized by pus-filled blisters that form on the skin, before hardening and falling off; smallpox often caused severe scarring and even blindness among those who survived. The virus was used as a biological weapon, notably by the British against Native Americans in Pontiac's War of the 1760s. The disease was 90% fatal among the Amerindian population, causing mass destruction. Before a vaccine was developed, the virus was managed through a process of inoculation--also called variolation--whereby a small amount of infected fluid, often from a cow, was introduced to a healthy person's body, causing an immune response. This process of inoculation was practiced in Asia and Africa, before appearing in the Ottoman Empire, where Mary Wortley Montagu witnessed the procedure. To read more, see Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation. - [BehnBurney19] FLAVIA. 1THE wretched FLAVIA on her couch reclin'd, 2Thus breath'd the anguish of a wounded mind; 3A glass revers'd in her right hand she bore, 4For now she shun'd the face she sought before. 5'How am I chang'd! alas! how am I grown 6'A frightful spectre, to myself unknown! 7'Where's my complexion? where my radiant bloom, 8'That promis'd happiness for years to come? 9'Then with what pleasure I this face survey'd! 10'To look once more, my visits oft delay'd! 11'Charm'd with the view, a fresher red would rise, 12'And a new life shot sparkling from my eyes! 33 13'Ah! faithless glass, my wonted bloom restore; 14'Alas! I rave, that bloom is now no more! 15'The greatest good the Gods on men bestow, 16'Ev'n youth itself, to me is useless now. 17'There was a time (oh! that I cou'd forget!) 18'When opera-ticketsopera-tickets pour’d before my feet; opera-ticketsOpera was a fashionable entertainment past-time in the eighteenth century. Opera stars were celebrities, often extravagantly-compensated, and also the subject of some criticism, as Michael Burden describes in "Opera, Excess, and the Discourse of Luxury in Eighteenth-Century England." Here, Flavia claims that "opera-tickets pour'd before [her] feet," which would have been an extravagance, indeed. According to Judith Milhous and Robert Hume, throughout much of the period ticket prices were fixed at 1s 6d or 5s, for pit/boxes or gallery seating, respectively. "A season subscription for fifty nights," they note, "was 15 [guineas]" (79). For more information on eighteenth-century opera, see this overview from the Victoria and Albert Museum. For more information on cost of living in the early eighteenth century, see the discussion of coinage at the Old Bailey Online. - [TH] 19'And at the ringring, where brightest beauties shine, ring

The "ring"

referred to a circular path in Hyde Park where fashionable people would walk,

ride, or take a carriage ride. It was a place to be seen. You can see a

rendering of the Ring in the detail, included here, of the 1833 map of London

engraved by William Smollinger. For more information on Hyde Park, see article from

Wikipedia. - [LR]

20'The earliest cherries of the spring were mine.

21'Witness, O

Lilly; and thou, MotteuxLilly, tell

LillyCharles

Lilly, also known as Charles Lille, "opened a perfume shop on The Strand in London in 1708 where he sold ‘snuffs

and perfumes that refresh the brain.’" Peter Motteux, author, also

owned an "India house" on Leadenhall Street that sold oriental goods. For more

information about Motteux and his shop, see Wikipedia

and British History Online. - [LR]

22'How much japanJapan these eyes have

made ye sell.

JapanJapanese

artifacts with painted or vanished design. A fashionable item that would be

found in Motteux's store. For more information, see this

article on East Asian lacquer from the Victoria and Albert

Museum. - [LR]

23'With what contempt ye saw me oft despise

24'The humble offer of the raffled prize;

25'For at the raffle still each prize I bore,

26'With scorn rejected, or with triumph wore!

27'Now beauty's fled, and presents are no more!

28'For me the Patriot has the house forsook,

29'And left debates to catch a passing look:

30'For me the Soldier has soft verses writ;

31'For me the Beaubeau_ has aim'd to be

a wit.

beauFrom the French, a beau is a ladies' man, or a suitor, often very fashionable (OED).

34

32'For me the Witwit to nonsense was

betray'd;

witUsed here as a noun, a wit was (usually) a man known for cleverness or wittiness (OED).

33'The Gamester has for me his dundun

delay'd,

dunUsed here as a noun, a dun in this sense is a demand for payment of a debt (OED). - [BehnBurney19]

34'And overseen the card I would have pay'd.

35'The bold and haughty by success made vain,

36'Aw'd by my eyes, have trembled to complain:

37'The bashful 'Squire touch'd by a wish unknown,

38'Has dar'd to speak with spirit not his own;

39'Fir'd by one wish, all did alike adore;

40'Now beauty's fled, and lovers are no more!

41'As round the room I turn my weeping eyes,

42'New unaffected scenes of sorrow rise!

43'Far from my sight that killing picture bear,

44'The face disfigure, and the canvas tear!

45'That picture, which with pride I us'd to show,

46'The lost resemblance but upbraids me now.

47'And thou, my toilettetoilette! where I

oft have sate,

toiletteFlavia's toilette is her dressing table. The word is used in multiple senses, either to refer to the location of the action of dressing and readying oneself for the day or as a collective term for the items of dressing or applying makeup (OED). - [BehnBurney19]

48'While hours unheeded pass'd in deep debate,

49'How curls should fall, or where a patchpatch to place;

patch

The "ring"

referred to a circular path in Hyde Park where fashionable people would walk,

ride, or take a carriage ride. It was a place to be seen. You can see a

rendering of the Ring in the detail, included here, of the 1833 map of London

engraved by William Smollinger. For more information on Hyde Park, see article from

Wikipedia. - [LR]

20'The earliest cherries of the spring were mine.

21'Witness, O

Lilly; and thou, MotteuxLilly, tell

LillyCharles

Lilly, also known as Charles Lille, "opened a perfume shop on The Strand in London in 1708 where he sold ‘snuffs

and perfumes that refresh the brain.’" Peter Motteux, author, also

owned an "India house" on Leadenhall Street that sold oriental goods. For more

information about Motteux and his shop, see Wikipedia

and British History Online. - [LR]

22'How much japanJapan these eyes have

made ye sell.

JapanJapanese

artifacts with painted or vanished design. A fashionable item that would be

found in Motteux's store. For more information, see this

article on East Asian lacquer from the Victoria and Albert

Museum. - [LR]

23'With what contempt ye saw me oft despise

24'The humble offer of the raffled prize;

25'For at the raffle still each prize I bore,

26'With scorn rejected, or with triumph wore!

27'Now beauty's fled, and presents are no more!

28'For me the Patriot has the house forsook,

29'And left debates to catch a passing look:

30'For me the Soldier has soft verses writ;

31'For me the Beaubeau_ has aim'd to be

a wit.

beauFrom the French, a beau is a ladies' man, or a suitor, often very fashionable (OED).

34

32'For me the Witwit to nonsense was

betray'd;

witUsed here as a noun, a wit was (usually) a man known for cleverness or wittiness (OED).

33'The Gamester has for me his dundun

delay'd,

dunUsed here as a noun, a dun in this sense is a demand for payment of a debt (OED). - [BehnBurney19]

34'And overseen the card I would have pay'd.

35'The bold and haughty by success made vain,

36'Aw'd by my eyes, have trembled to complain:

37'The bashful 'Squire touch'd by a wish unknown,

38'Has dar'd to speak with spirit not his own;

39'Fir'd by one wish, all did alike adore;

40'Now beauty's fled, and lovers are no more!

41'As round the room I turn my weeping eyes,

42'New unaffected scenes of sorrow rise!

43'Far from my sight that killing picture bear,

44'The face disfigure, and the canvas tear!

45'That picture, which with pride I us'd to show,

46'The lost resemblance but upbraids me now.

47'And thou, my toilettetoilette! where I

oft have sate,

toiletteFlavia's toilette is her dressing table. The word is used in multiple senses, either to refer to the location of the action of dressing and readying oneself for the day or as a collective term for the items of dressing or applying makeup (OED). - [BehnBurney19]

48'While hours unheeded pass'd in deep debate,

49'How curls should fall, or where a patchpatch to place;

patch A patch in this sense has a specific historical meaning, now obsolete. In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was common for fasionable people to wear "patches," or small pieces of black silk or velvet, sometimes cut into shapes. These patches--called "les mouches" in French, because they resembled a fly--would be worn on the face, sometimes to cover a blemish or simply for fashionable purposes, as an artificial beauty mark. Patches were also sometimes used to declare a particular loyalty or party. To learn more about patches, see the Collector's Weekly article, "That Time the French Aristocracy Was Obsessed With Sexy Face Stickers." The image included here, from that article (via the Metropolitan Museum of Art), is an engraving showing a fashionable young woman at her toilette; she has two patches on her cheek. Engraving “The Morning: The Woman at Her Toilet” by Gilles-Edme Petit, c. 1745-1760. - [TH]

50'If blue or scarlet best became my face;

35

51'Now on some happier nymphnymph your

aid bestow;

nymphAccording to

the OED, "nymph" (n1. 1-3) is a poetic way of describing a beautiful young

woman. It derives from classical mythology, but also can suggest an ironic

usage. - [TH]

52'On fairer heads, ye useless jewels, glow!

53'No borrow'd lusture can my charms restore;

54'Beauty is fled, and dress is now no more!

55'Ye meaner beauties, I permit ye shine;

56'Go, triumph in the hearts that once were mine;

57'But 'midst your triumphs with confusion know,

58''Tis to my ruin all your arms ye owe.

59'Would pitying heav'n restore my wonted mein,

60'Ye still might move unthought-of and unseen:

61'But oh! how vain, how wretched is the boast

62'Of beauty faded, and of empire lost!

63'What now is left but weeping, to deplore

64'My beauty fled, and empire now no more!

65'Ye, cruel Chymists, what with-held your aid!

66'Could no pomatumspomatums save a

trembling maid?

pomatumsPomatum, or pomade, refers to a cosmetic applied to the face--often, it was made with lead, and used to add a whiteness to the skin (OED). - [TH]

67'How false and trifling is that art ye boast;

68'No art can give me back my beauty lost.

69'In tears, surrounded by my friends I lay,

70'Mask'd o'er and trembled at the

sight of day;

36

71'MIRMILIOMirmilio came my fortune to

deplore,

MirmilioIn these

lines, Montagu invokes characters from Samuel Garth's popular early mock-epic

poem, "The Dispensary" (1699). According to Sarah Gillam, writing for the Royal College of Physicians, Mirmillo

likely represents William Gibbons, one of the physicians caught up in the late

17th century dispute about whether to open a free dispensary for the health of

the poor in London. - [TH]

72'(A golden headed cane well carv'd he bore)

73'Cordials, he cried, my spirits must restore:

74'Beauty is fled, and spirit is no more!

75'GALENGalen, the grave;

officious SQUIRTSquirt, was there,

GalenWhile not referenced in Garth's

"Dispensary," Galen is

a Greek physician (129-216 CE) known for pioneering work in anatomy, among

other branches of medicine and philosophy. His humoral work was highly

influential in the Medieval and Early Modern periods.

SquirtAnother

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Squirt--always designated there

"officious"--is an assistant to Horoscope, the chief apothecary in the poem,

who revives his master with a squirt from a urinal at the end of Canto II: Oft he essay'd the Magus to

restore,

By Salt of Succinum's prevailing pow'r;

But still supine the solid Lumber lay,

An Image of scarce animated Clay; Till Fates, indulgent when

Disasters call, Bethought th' Assistant of a Urinal; Whose

Steam the Wight no sooner did receive, But rowz'd, and blest the

Stale Restorative. The Springs of Life their former Vigour feel,

Such Zeal he had for that vile Urensil.

- [TH]

76'With fruitless grief and unavailing care:

77'MACHAONMachaon too, the great MACHAON,

known

MachaonAnother

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Machaon there represents a late

seventeenth-century physician Sir Thomas Millington (Gillum). Machaon is also the name of a mythic figure, the son of the

Greco-Roman god of medicine Asclepius. In The Illiad, Machaon was the surgeon for the Greek army

during the Trojan War. - [TH]

78'By his red cloak and his superior frown;

79 'And why, he cry'd, this grief and this despair?

80'You shall again be well, again be fair;

81'Believe my oath; (with that an oath he swore)

82'False was his oath; my beauty is no more!

83'Cease, hapless maid no more thy tale pursue,

84'Forsake mankind, and bid the world adieu!

85'Monarchs and beauties rule with equal sway;

86'All strive to serve, and glory to obey:

87'Alike unpitied when depos'd they grow;

88'Men mock the idol of their former vow.

89'Adieu! ye parks!—in some obscure recess,

90'Where gentle streams will weep at my distress,

37

91'Where no false friend will in my grief take part,

92'And mourn my ruin with a joyful heart;

93'There let me live in some deserted place,

94'There hide in shades this lost inglorious face.

95'Ye operas, circles, I no more must view!

96'My toilette, patches, all the world adieu!

A patch in this sense has a specific historical meaning, now obsolete. In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was common for fasionable people to wear "patches," or small pieces of black silk or velvet, sometimes cut into shapes. These patches--called "les mouches" in French, because they resembled a fly--would be worn on the face, sometimes to cover a blemish or simply for fashionable purposes, as an artificial beauty mark. Patches were also sometimes used to declare a particular loyalty or party. To learn more about patches, see the Collector's Weekly article, "That Time the French Aristocracy Was Obsessed With Sexy Face Stickers." The image included here, from that article (via the Metropolitan Museum of Art), is an engraving showing a fashionable young woman at her toilette; she has two patches on her cheek. Engraving “The Morning: The Woman at Her Toilet” by Gilles-Edme Petit, c. 1745-1760. - [TH]

50'If blue or scarlet best became my face;

35

51'Now on some happier nymphnymph your

aid bestow;

nymphAccording to

the OED, "nymph" (n1. 1-3) is a poetic way of describing a beautiful young

woman. It derives from classical mythology, but also can suggest an ironic

usage. - [TH]

52'On fairer heads, ye useless jewels, glow!

53'No borrow'd lusture can my charms restore;

54'Beauty is fled, and dress is now no more!

55'Ye meaner beauties, I permit ye shine;

56'Go, triumph in the hearts that once were mine;

57'But 'midst your triumphs with confusion know,

58''Tis to my ruin all your arms ye owe.

59'Would pitying heav'n restore my wonted mein,

60'Ye still might move unthought-of and unseen:

61'But oh! how vain, how wretched is the boast

62'Of beauty faded, and of empire lost!

63'What now is left but weeping, to deplore

64'My beauty fled, and empire now no more!

65'Ye, cruel Chymists, what with-held your aid!

66'Could no pomatumspomatums save a

trembling maid?

pomatumsPomatum, or pomade, refers to a cosmetic applied to the face--often, it was made with lead, and used to add a whiteness to the skin (OED). - [TH]

67'How false and trifling is that art ye boast;

68'No art can give me back my beauty lost.

69'In tears, surrounded by my friends I lay,

70'Mask'd o'er and trembled at the

sight of day;

36

71'MIRMILIOMirmilio came my fortune to

deplore,

MirmilioIn these

lines, Montagu invokes characters from Samuel Garth's popular early mock-epic

poem, "The Dispensary" (1699). According to Sarah Gillam, writing for the Royal College of Physicians, Mirmillo

likely represents William Gibbons, one of the physicians caught up in the late

17th century dispute about whether to open a free dispensary for the health of

the poor in London. - [TH]

72'(A golden headed cane well carv'd he bore)

73'Cordials, he cried, my spirits must restore:

74'Beauty is fled, and spirit is no more!

75'GALENGalen, the grave;

officious SQUIRTSquirt, was there,

GalenWhile not referenced in Garth's

"Dispensary," Galen is

a Greek physician (129-216 CE) known for pioneering work in anatomy, among

other branches of medicine and philosophy. His humoral work was highly

influential in the Medieval and Early Modern periods.

SquirtAnother

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Squirt--always designated there

"officious"--is an assistant to Horoscope, the chief apothecary in the poem,

who revives his master with a squirt from a urinal at the end of Canto II: Oft he essay'd the Magus to

restore,

By Salt of Succinum's prevailing pow'r;

But still supine the solid Lumber lay,

An Image of scarce animated Clay; Till Fates, indulgent when

Disasters call, Bethought th' Assistant of a Urinal; Whose

Steam the Wight no sooner did receive, But rowz'd, and blest the

Stale Restorative. The Springs of Life their former Vigour feel,

Such Zeal he had for that vile Urensil.

- [TH]

76'With fruitless grief and unavailing care:

77'MACHAONMachaon too, the great MACHAON,

known

MachaonAnother

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Machaon there represents a late

seventeenth-century physician Sir Thomas Millington (Gillum). Machaon is also the name of a mythic figure, the son of the

Greco-Roman god of medicine Asclepius. In The Illiad, Machaon was the surgeon for the Greek army

during the Trojan War. - [TH]

78'By his red cloak and his superior frown;

79 'And why, he cry'd, this grief and this despair?

80'You shall again be well, again be fair;

81'Believe my oath; (with that an oath he swore)

82'False was his oath; my beauty is no more!

83'Cease, hapless maid no more thy tale pursue,

84'Forsake mankind, and bid the world adieu!

85'Monarchs and beauties rule with equal sway;

86'All strive to serve, and glory to obey:

87'Alike unpitied when depos'd they grow;

88'Men mock the idol of their former vow.

89'Adieu! ye parks!—in some obscure recess,

90'Where gentle streams will weep at my distress,

37

91'Where no false friend will in my grief take part,

92'And mourn my ruin with a joyful heart;

93'There let me live in some deserted place,

94'There hide in shades this lost inglorious face.

95'Ye operas, circles, I no more must view!

96'My toilette, patches, all the world adieu!

Footnotes

montagu_ Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, born

Pierrepont (1689-1762), was an eccentric woman and talented writer who has not

received as much attention as her friends and contemporaries, like Alexander Pope,

with whom she had a close relationship before it turned acrimonious. Montagu was a

member of the aristocracy, daughter of the Earl of Kingston and Lady Mary Fielding

(yes, she was related to the Henry Fielding of Tom Jones

fame!). She fled an arranged marriage and eloped with Edward Wortley Montagu. Most

remember her as a letter-writer, whose letters were designed for posthumous

publication. Most significant in these letters are those typically referred to as

the "Turkish Embassy" letters, because they discuss her experience traveling to

and living in Contantinople (now Istanbul) with her husband, who served as

ambassador to Turkey from 1716-1718.

Her "Town Eclogues," from which this

selection is taken, are a series of six adaptations of the Roman poet Virgil’s

Eclogues, written in 37BCE. An "eclogue" is a kind of poem that presents a snippet

(or a "selection") of life. In Virgil’s eclogues—a series of 10 poems—rural

herdsman sing and discuss their experiences, often relating to the turbulent time

in Rome just as the Roman Empire was emerging. In the early 18th century,

"Augustan" British poets saw themselves as modern inheritors of a Roman tradition

inaugurated by Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome.

Montagu’s eclogues focus

similarly on a turbulent, transitional era characterized by the social, political,

and economic structures of rapid commercialization in the England and the United

Kingdom. These "Town Eclogues" offer a series of six poems, which you can read in

their entirety on Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive. The poems are organized by days of

the week and discuss themes of sexuality, relationships between men and women,

illness, and fashionable society. In this poem, "Saturday; or the Small-Pox," the

poetic speaker recounts the character Flavia’s thoughts about her smallpox scars,

which were shared by Mary Wortley Montagu herself—Montagu suffered from smallpox

in her youth, which marked her for the rest of her life. During her travels to

Turkey, she witnessed the act of inoculation for smallpox, which she employed to

inoculate her children. She brought word of the innovation back to England, though

she is not credited with its popularization. To read more about Montagu’s

connection with the smallpox vaccine, read Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation.

In

1736, Montagu fell in love with an Italian writer, and she left her husband and

family to live with him on the Continent, under cover of traveling for health

reasons. He never caught up with her in Italy, however, and she traveled through

France and Italy in the 40s and 50s, living for a decade with an Italian Count.

After her husband died in 1761, she returned to London, and died of cancer shortly

after. Her letters were published in 1763, but the first complete modern edition

was published in the 1960s. The portrait of Montagu included here was painted in

1725 by Jonathan Richardson. It is currently in the collection of the Earl of

Harrowby, Stafford (via Wikimedia Commons).

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, born

Pierrepont (1689-1762), was an eccentric woman and talented writer who has not

received as much attention as her friends and contemporaries, like Alexander Pope,

with whom she had a close relationship before it turned acrimonious. Montagu was a

member of the aristocracy, daughter of the Earl of Kingston and Lady Mary Fielding

(yes, she was related to the Henry Fielding of Tom Jones

fame!). She fled an arranged marriage and eloped with Edward Wortley Montagu. Most

remember her as a letter-writer, whose letters were designed for posthumous

publication. Most significant in these letters are those typically referred to as

the "Turkish Embassy" letters, because they discuss her experience traveling to

and living in Contantinople (now Istanbul) with her husband, who served as

ambassador to Turkey from 1716-1718.

Her "Town Eclogues," from which this

selection is taken, are a series of six adaptations of the Roman poet Virgil’s

Eclogues, written in 37BCE. An "eclogue" is a kind of poem that presents a snippet

(or a "selection") of life. In Virgil’s eclogues—a series of 10 poems—rural

herdsman sing and discuss their experiences, often relating to the turbulent time

in Rome just as the Roman Empire was emerging. In the early 18th century,

"Augustan" British poets saw themselves as modern inheritors of a Roman tradition

inaugurated by Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome.

Montagu’s eclogues focus

similarly on a turbulent, transitional era characterized by the social, political,

and economic structures of rapid commercialization in the England and the United

Kingdom. These "Town Eclogues" offer a series of six poems, which you can read in

their entirety on Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive. The poems are organized by days of

the week and discuss themes of sexuality, relationships between men and women,

illness, and fashionable society. In this poem, "Saturday; or the Small-Pox," the

poetic speaker recounts the character Flavia’s thoughts about her smallpox scars,

which were shared by Mary Wortley Montagu herself—Montagu suffered from smallpox

in her youth, which marked her for the rest of her life. During her travels to

Turkey, she witnessed the act of inoculation for smallpox, which she employed to

inoculate her children. She brought word of the innovation back to England, though

she is not credited with its popularization. To read more about Montagu’s

connection with the smallpox vaccine, read Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation.

In

1736, Montagu fell in love with an Italian writer, and she left her husband and

family to live with him on the Continent, under cover of traveling for health

reasons. He never caught up with her in Italy, however, and she traveled through

France and Italy in the 40s and 50s, living for a decade with an Italian Count.

After her husband died in 1761, she returned to London, and died of cancer shortly

after. Her letters were published in 1763, but the first complete modern edition

was published in the 1960s. The portrait of Montagu included here was painted in

1725 by Jonathan Richardson. It is currently in the collection of the Earl of

Harrowby, Stafford (via Wikimedia Commons).

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, born

Pierrepont (1689-1762), was an eccentric woman and talented writer who has not

received as much attention as her friends and contemporaries, like Alexander Pope,

with whom she had a close relationship before it turned acrimonious. Montagu was a

member of the aristocracy, daughter of the Earl of Kingston and Lady Mary Fielding

(yes, she was related to the Henry Fielding of Tom Jones

fame!). She fled an arranged marriage and eloped with Edward Wortley Montagu. Most

remember her as a letter-writer, whose letters were designed for posthumous

publication. Most significant in these letters are those typically referred to as

the "Turkish Embassy" letters, because they discuss her experience traveling to

and living in Contantinople (now Istanbul) with her husband, who served as

ambassador to Turkey from 1716-1718.

Her "Town Eclogues," from which this

selection is taken, are a series of six adaptations of the Roman poet Virgil’s

Eclogues, written in 37BCE. An "eclogue" is a kind of poem that presents a snippet

(or a "selection") of life. In Virgil’s eclogues—a series of 10 poems—rural

herdsman sing and discuss their experiences, often relating to the turbulent time

in Rome just as the Roman Empire was emerging. In the early 18th century,

"Augustan" British poets saw themselves as modern inheritors of a Roman tradition

inaugurated by Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome.

Montagu’s eclogues focus

similarly on a turbulent, transitional era characterized by the social, political,

and economic structures of rapid commercialization in the England and the United

Kingdom. These "Town Eclogues" offer a series of six poems, which you can read in

their entirety on Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive. The poems are organized by days of

the week and discuss themes of sexuality, relationships between men and women,

illness, and fashionable society. In this poem, "Saturday; or the Small-Pox," the

poetic speaker recounts the character Flavia’s thoughts about her smallpox scars,

which were shared by Mary Wortley Montagu herself—Montagu suffered from smallpox

in her youth, which marked her for the rest of her life. During her travels to

Turkey, she witnessed the act of inoculation for smallpox, which she employed to

inoculate her children. She brought word of the innovation back to England, though

she is not credited with its popularization. To read more about Montagu’s

connection with the smallpox vaccine, read Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation.

In

1736, Montagu fell in love with an Italian writer, and she left her husband and

family to live with him on the Continent, under cover of traveling for health

reasons. He never caught up with her in Italy, however, and she traveled through

France and Italy in the 40s and 50s, living for a decade with an Italian Count.

After her husband died in 1761, she returned to London, and died of cancer shortly

after. Her letters were published in 1763, but the first complete modern edition

was published in the 1960s. The portrait of Montagu included here was painted in

1725 by Jonathan Richardson. It is currently in the collection of the Earl of

Harrowby, Stafford (via Wikimedia Commons).

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, born

Pierrepont (1689-1762), was an eccentric woman and talented writer who has not

received as much attention as her friends and contemporaries, like Alexander Pope,

with whom she had a close relationship before it turned acrimonious. Montagu was a

member of the aristocracy, daughter of the Earl of Kingston and Lady Mary Fielding

(yes, she was related to the Henry Fielding of Tom Jones

fame!). She fled an arranged marriage and eloped with Edward Wortley Montagu. Most

remember her as a letter-writer, whose letters were designed for posthumous

publication. Most significant in these letters are those typically referred to as

the "Turkish Embassy" letters, because they discuss her experience traveling to

and living in Contantinople (now Istanbul) with her husband, who served as

ambassador to Turkey from 1716-1718.

Her "Town Eclogues," from which this

selection is taken, are a series of six adaptations of the Roman poet Virgil’s

Eclogues, written in 37BCE. An "eclogue" is a kind of poem that presents a snippet

(or a "selection") of life. In Virgil’s eclogues—a series of 10 poems—rural

herdsman sing and discuss their experiences, often relating to the turbulent time

in Rome just as the Roman Empire was emerging. In the early 18th century,

"Augustan" British poets saw themselves as modern inheritors of a Roman tradition

inaugurated by Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome.

Montagu’s eclogues focus

similarly on a turbulent, transitional era characterized by the social, political,

and economic structures of rapid commercialization in the England and the United

Kingdom. These "Town Eclogues" offer a series of six poems, which you can read in

their entirety on Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive. The poems are organized by days of

the week and discuss themes of sexuality, relationships between men and women,

illness, and fashionable society. In this poem, "Saturday; or the Small-Pox," the

poetic speaker recounts the character Flavia’s thoughts about her smallpox scars,

which were shared by Mary Wortley Montagu herself—Montagu suffered from smallpox

in her youth, which marked her for the rest of her life. During her travels to

Turkey, she witnessed the act of inoculation for smallpox, which she employed to

inoculate her children. She brought word of the innovation back to England, though

she is not credited with its popularization. To read more about Montagu’s

connection with the smallpox vaccine, read Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation.

In

1736, Montagu fell in love with an Italian writer, and she left her husband and

family to live with him on the Continent, under cover of traveling for health

reasons. He never caught up with her in Italy, however, and she traveled through

France and Italy in the 40s and 50s, living for a decade with an Italian Count.

After her husband died in 1761, she returned to London, and died of cancer shortly

after. Her letters were published in 1763, but the first complete modern edition

was published in the 1960s. The portrait of Montagu included here was painted in

1725 by Jonathan Richardson. It is currently in the collection of the Earl of

Harrowby, Stafford (via Wikimedia Commons).smallpox_Smallpox is an infectious disease caused by the

variola virus, which ravaged many parts of the world until its eradication in

1980. Throughout the eighteenth century, over 400,000 people died in Europe from

the disease. It is characterized by pus-filled blisters that form on the skin,

before hardening and falling off; smallpox often caused severe scarring and even

blindness among those who survived. The virus was used as a biological weapon,

notably by the British against Native Americans in Pontiac's War of the 1760s. The

disease was 90% fatal among the Amerindian population, causing mass destruction.

Before a vaccine was developed, the virus was managed through a process of

inoculation--also called variolation--whereby a small amount of infected fluid,

often from a cow, was introduced to a healthy person's body, causing an immune

response. This process of inoculation was practiced in Asia and Africa, before

appearing in the Ottoman Empire, where Mary Wortley Montagu witnessed the

procedure. To read more, see Tom Solomon’s article on The Conversation.

opera-tickets_Opera was

a fashionable entertainment past-time in the eighteenth century. Opera stars

were celebrities, often extravagantly-compensated, and also the subject of some

criticism, as Michael

Burden describes in "Opera, Excess, and the Discourse of Luxury in

Eighteenth-Century England." Here, Flavia claims that "opera-tickets pour'd

before [her] feet," which would have been an extravagance, indeed. According to

Judith Milhous and Robert Hume, throughout much of the period ticket prices

were fixed at 1s 6d or 5s, for pit/boxes or gallery seating, respectively. "A

season subscription for fifty nights," they note, "was 15 [guineas]" (79). For more information

on eighteenth-century opera, see this

overview from the Victoria and Albert Museum. For more information on

cost of living in the early eighteenth century, see the discussion of

coinage at the Old Bailey Online.

ring_ The "ring"

referred to a circular path in Hyde Park where fashionable people would walk,

ride, or take a carriage ride. It was a place to be seen. You can see a

rendering of the Ring in the detail, included here, of the 1833 map of London

engraved by William Smollinger. For more information on Hyde Park, see article from

Wikipedia.

The "ring"

referred to a circular path in Hyde Park where fashionable people would walk,

ride, or take a carriage ride. It was a place to be seen. You can see a

rendering of the Ring in the detail, included here, of the 1833 map of London

engraved by William Smollinger. For more information on Hyde Park, see article from

Wikipedia.

The "ring"

referred to a circular path in Hyde Park where fashionable people would walk,

ride, or take a carriage ride. It was a place to be seen. You can see a

rendering of the Ring in the detail, included here, of the 1833 map of London

engraved by William Smollinger. For more information on Hyde Park, see article from

Wikipedia.

The "ring"

referred to a circular path in Hyde Park where fashionable people would walk,

ride, or take a carriage ride. It was a place to be seen. You can see a

rendering of the Ring in the detail, included here, of the 1833 map of London

engraved by William Smollinger. For more information on Hyde Park, see article from

Wikipedia.Lilly_Charles

Lilly, also known as Charles Lille, "opened a perfume shop on The Strand in London in 1708 where he sold ‘snuffs

and perfumes that refresh the brain.’" Peter Motteux, author, also

owned an "India house" on Leadenhall Street that sold oriental goods. For more

information about Motteux and his shop, see Wikipedia

and British History Online.

Japan_Japanese

artifacts with painted or vanished design. A fashionable item that would be

found in Motteux's store. For more information, see this

article on East Asian lacquer from the Victoria and Albert

Museum.

dun_Used here as a noun, a dun in this sense is a demand for payment of a debt (OED).

toilette_Flavia's toilette is her dressing table. The word is used in multiple senses, either to refer to the location of the action of dressing and readying oneself for the day or as a collective term for the items of dressing or applying makeup (OED).

patch_ A patch in this sense has a specific historical meaning, now obsolete. In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was common for fasionable people to wear "patches," or small pieces of black silk or velvet, sometimes cut into shapes. These patches--called "les mouches" in French, because they resembled a fly--would be worn on the face, sometimes to cover a blemish or simply for fashionable purposes, as an artificial beauty mark. Patches were also sometimes used to declare a particular loyalty or party. To learn more about patches, see the Collector's Weekly article, "That Time the French Aristocracy Was Obsessed With Sexy Face Stickers." The image included here, from that article (via the Metropolitan Museum of Art), is an engraving showing a fashionable young woman at her toilette; she has two patches on her cheek. Engraving “The Morning: The Woman at Her Toilet” by Gilles-Edme Petit, c. 1745-1760.

A patch in this sense has a specific historical meaning, now obsolete. In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was common for fasionable people to wear "patches," or small pieces of black silk or velvet, sometimes cut into shapes. These patches--called "les mouches" in French, because they resembled a fly--would be worn on the face, sometimes to cover a blemish or simply for fashionable purposes, as an artificial beauty mark. Patches were also sometimes used to declare a particular loyalty or party. To learn more about patches, see the Collector's Weekly article, "That Time the French Aristocracy Was Obsessed With Sexy Face Stickers." The image included here, from that article (via the Metropolitan Museum of Art), is an engraving showing a fashionable young woman at her toilette; she has two patches on her cheek. Engraving “The Morning: The Woman at Her Toilet” by Gilles-Edme Petit, c. 1745-1760.

A patch in this sense has a specific historical meaning, now obsolete. In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was common for fasionable people to wear "patches," or small pieces of black silk or velvet, sometimes cut into shapes. These patches--called "les mouches" in French, because they resembled a fly--would be worn on the face, sometimes to cover a blemish or simply for fashionable purposes, as an artificial beauty mark. Patches were also sometimes used to declare a particular loyalty or party. To learn more about patches, see the Collector's Weekly article, "That Time the French Aristocracy Was Obsessed With Sexy Face Stickers." The image included here, from that article (via the Metropolitan Museum of Art), is an engraving showing a fashionable young woman at her toilette; she has two patches on her cheek. Engraving “The Morning: The Woman at Her Toilet” by Gilles-Edme Petit, c. 1745-1760.

A patch in this sense has a specific historical meaning, now obsolete. In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was common for fasionable people to wear "patches," or small pieces of black silk or velvet, sometimes cut into shapes. These patches--called "les mouches" in French, because they resembled a fly--would be worn on the face, sometimes to cover a blemish or simply for fashionable purposes, as an artificial beauty mark. Patches were also sometimes used to declare a particular loyalty or party. To learn more about patches, see the Collector's Weekly article, "That Time the French Aristocracy Was Obsessed With Sexy Face Stickers." The image included here, from that article (via the Metropolitan Museum of Art), is an engraving showing a fashionable young woman at her toilette; she has two patches on her cheek. Engraving “The Morning: The Woman at Her Toilet” by Gilles-Edme Petit, c. 1745-1760.nymph_According to

the OED, "nymph" (n1. 1-3) is a poetic way of describing a beautiful young

woman. It derives from classical mythology, but also can suggest an ironic

usage.

pomatums_Pomatum, or pomade, refers to a cosmetic applied to the face--often, it was made with lead, and used to add a whiteness to the skin (OED).

Mirmilio_In these

lines, Montagu invokes characters from Samuel Garth's popular early mock-epic

poem, "The Dispensary" (1699). According to Sarah Gillam, writing for the Royal College of Physicians, Mirmillo

likely represents William Gibbons, one of the physicians caught up in the late

17th century dispute about whether to open a free dispensary for the health of

the poor in London.

Galen_While not referenced in Garth's

"Dispensary," Galen is

a Greek physician (129-216 CE) known for pioneering work in anatomy, among

other branches of medicine and philosophy. His humoral work was highly

influential in the Medieval and Early Modern periods.

Squirt_Another

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Squirt--always designated there

"officious"--is an assistant to Horoscope, the chief apothecary in the poem,

who revives his master with a squirt from a urinal at the end of Canto II: Oft he essay'd the Magus to

restore,

By Salt of Succinum's prevailing pow'r;

But still supine the solid Lumber lay,

An Image of scarce animated Clay; Till Fates, indulgent when

Disasters call, Bethought th' Assistant of a Urinal; Whose

Steam the Wight no sooner did receive, But rowz'd, and blest the

Stale Restorative. The Springs of Life their former Vigour feel,

Such Zeal he had for that vile Urensil.

Machaon_Another

character in Garth's "Dispensary," Machaon there represents a late

seventeenth-century physician Sir Thomas Millington (Gillum). Machaon is also the name of a mythic figure, the son of the

Greco-Roman god of medicine Asclepius. In The Illiad, Machaon was the surgeon for the Greek army

during the Trojan War.