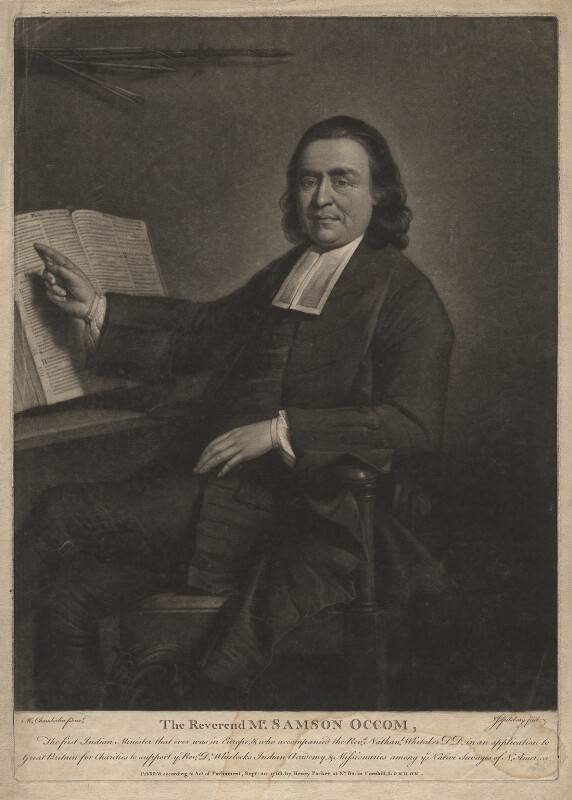

The Female American; Or, The Adventures of Unca Eliza Winkfield

(Vol. I)

By

Unca Eliza Winkfield

OR, THE ADVENTURES

OF UNCA ELIZA WINKFIELD,

COMPILED BY HERSELF.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

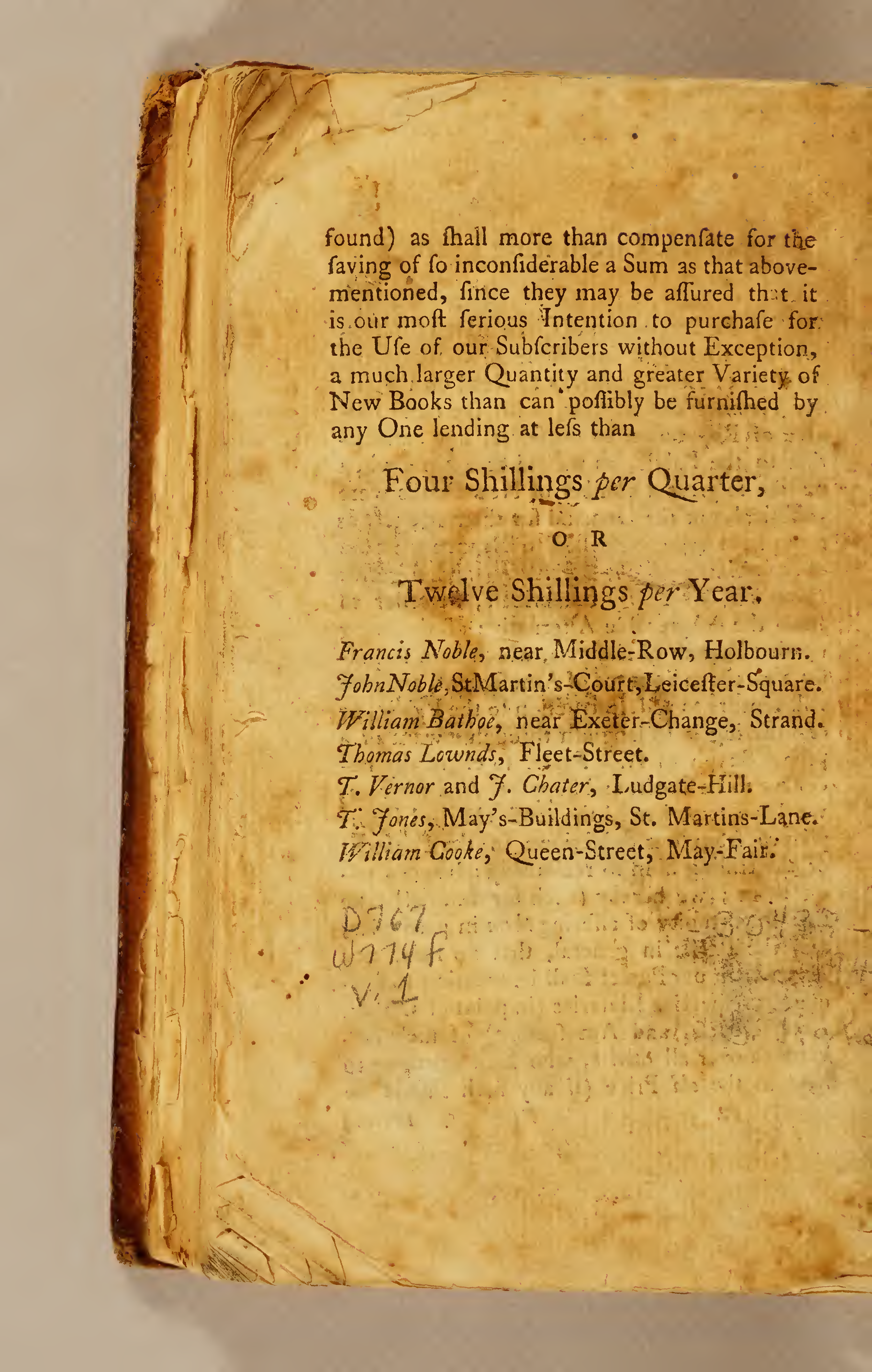

Printed for FRANCIS NOBLE, at his Circulating

Library, opposite Gray's-Inn Gate, Holbourn;

AND JOHN NOBLE, at his Circulating Library, in

St. Martin's-Court, near Leicester-Square.

MDCCLXVII. i ADVERTISEMENT.

THE following extraordinary History will prove either acceptable or not to the reader; in either case, it ought to be a matter of indifference to him from what quarter, or by what means, he receives it.

But if curiosity demands a satisfaction of this kind, all that he can receive is only this, that I found it among the papers of my late father.

Upon a perusal of it, I found it both pleasing and instructive, ii not unworthy of the most sensible reader; highly fit to be perused by the youth of both sexes, as a rational, moral entertainment; and, as such, I doubt not, but that it will descend to late posterity, when, most of its cotemporaries, founded only in fiction, will have been long forgotten.

The EDITOR. 1 THEFemale American;

OR THE

ADVENTURES

OF UNCA ELIZA WINKFIELD. CHAP. I. Motives for writing this history; discovery of Virginia; the author's grandfather settles there; he is killed by the natives; his son is taken prisoner, but is saved by one of the king's daughters.

THE following history of my life I never completely related but to one person; and at that time had no intention of committing it to writing: but finding the remembrance of 2it burdensome to my memory, I thought I might, in some degree, exonerate myself, by digesting the most material events in the form of an history; for which purpose I collected together such loose memorandums as I had occasionally made, which have enabled me to render the following relation more regular and complete than otherwise it could have been, had I been obliged to trust only to the power of recollection: how, and why, I afterwards came otherwise to dispose of it will appear in due time. The lives of women being commonly domestic, the occurrences of them are generally pretty nearly of the same kindwomenwomenThis introduction into the novel claims to make space for women within parts of life - and within literary genres - where many thought that only men could go. Mary Helen McMurran calls The Female American "an irresistible antidote to the two pillars of the eighteenth-century development of the realist novel: masculine individualism and female domesticity" ( "Realism and the Unreal in The Female American", 324). - [UOStudStaff] ; whilst those of men, frequently more vagrant, subject them often to experience greater vicissitudes, many times wonderful and strange. Though a woman, it has been my 3 lot to have experienced much of the latter; for so wonderful, strange, and uncommon have been the events of my life, that true history, perhaps, never recorded any that were more so. However, I shall not endeavour to extort the reader's credence of them, if such my work should ever have any, by solemn professions of veracity; for, perhaps, they may never be read; but if they should, I think the greatest sceptic will allow, uncommon as they are, that they do not exceed the bounds of probability. Here are two ends they cannot fail of answering, rational entertainment, and mental improvement. To proceed then:

The peaceful reign of king James I of

England gave opportunity to the first attempt of the English to

make a settlement4 [page breaks after 'settle-']

in the Indies, at a

place called, originally, WingandacoaWingandacoa

Wingandacoa

According to the Joyner Library at East Carolina University, "Wingandacoa" is

another name for the mainland of Virginia. - [UOStudStaff], part of the continent

adjoining to Florida, called

afterwards Virginia, in honour

of our maiden queen Elizabeth,

of blessed memory. As this place was first discovered by the great Sir Walter Raleigh, he obtained

letters patent to settle a plantation there, Anno Dom.

1584. But it was some years after that time before any

colony was sent there. The first plantation that proved successful, was began in 1607: at this time a colony arrived there of about an

hundred persons, among the conductors of whom was Mr. Edward Maria Winkfield, my grandfather; but

as many of these died, a further supply was sent the year after, under the care

of captain Nilson and again more in 1610, 1611, 1612.

According to the Joyner Library at East Carolina University, "Wingandacoa" is

another name for the mainland of Virginia. - [UOStudStaff], part of the continent

adjoining to Florida, called

afterwards Virginia, in honour

of our maiden queen Elizabeth,

of blessed memory. As this place was first discovered by the great Sir Walter Raleigh, he obtained

letters patent to settle a plantation there, Anno Dom.

1584. But it was some years after that time before any

colony was sent there. The first plantation that proved successful, was began in 1607: at this time a colony arrived there of about an

hundred persons, among the conductors of whom was Mr. Edward Maria Winkfield, my grandfather; but

as many of these died, a further supply was sent the year after, under the care

of captain Nilson and again more in 1610, 1611, 1612.

In 1618, the settlement was thought of consequence enough to receive a governor from England. A very large colony arrived there two years after; and now the newcomers formed themselves into corporations. The first, and principal town, was honoured with the name of king James. But the happy prospect, with which the newcomers flattered themselves, was unhappily obscured by the native Indians, who came unexpectedly upon them, and massacred three hundred of them; but this loss was soon repaired by a fresh recruit from England.---Thus much for the first peopling my native country.

The plantation which my grandfather first began, and which was the largest and most successful, devolved in a flourishing6 [page breaks after 'flou-'] state to my father, Mr. William Winkfield, of whom I must relate a very extraordinary adventure, as it gave occasion to his growing more suddenly rich than he could have done by an infant plantation, and gave birth to me; and in the consequences of it effected a more happy issue to my future adventures than could otherwise have happened.

At the time of the massacre, mentioned above, my grandfather was killed, and my father, with a few more, was taken prisoners by the Indians; and as it was a very dark night, was hurried along many miles before he could perfectly discover any objects: at length the rising sun discovered to his view, at some distance, a large river with a great number7 [page breaks after 'num-']number of boats on it; into one of these he was forced, and then bound hand and foot. In a little time all the boats were in motion, and for some hours continued to go with great rapidity. My father had now but too much time to reflect on his unpromising situation, and recalling to his mind the words of his elder brother, whom he had left in England, he thought them unhappily predictive.

He was a clergyman, and one of true piety and sound erudition. When his brother, my father, was about to quit England, with their father, to settle in this new discovered country, "My dear brother Bill," said he, "I know too well my duty to my father to remonstrate against any action of his, 8though in secret I may dread the consequence; but as I am your brother, and your elder, I may presume to give my opinion; may it not be prophetic! We have no right to invade the country of another, and I fear invaders will always meet a curse; but as your youth disenables you from viewing this expedition in that equitable light that it ought to be looked on, may your sufferings be proportionably light! for our God is just, and will weigh our actions in a just scale."

My father at this time was about twenty years old, of a remarkable fair complexion for a man, with brown hair, black eyes, and was well shaped. I 9should not give a description of his person, but that to it he owed, as it seems, his future preservation. The Indians continued their voyage above four or five hours, when they stopped on the same side of the shore on which they had embarked. As soon as they were landed, my father, with five other English captives, tied one to another, were drove, like sheep, many miles up the country, and then lodged in a cabin till next day; however, in the interim, they were plentifully supplied with dried Indian corn, dried goats flesh, and a kind of small wine, but thick, though well flavoured. They had heard that some of the Indians were men-eaterscannibals cannibalscannibals - [UOStudStaff], and thought these were such, or that they would not have fed them so plentifully but to render 10 them, as we do hogs, the better food: however, in this they were mistakenmistaken mistakenWinkfield’s father and companions are referred to twice in this passage as livestock (sheep, then hogs). Winkfield alludes to, then quickly dismisses, the possibility that the Indians are cannibals. The early rejection of a 'savage cannibal' trope in The Female American fundamentally changes Winkfield’s experience living on the island compared to Robinson Crusoe and the portrayal of the 'Indians' she encounters. - [UOStudStaff].

The next day, soon after sun-rising, my father and his five unhappy companions were brought out of their cabin; their cloathscloaths cloathsclothes - [UOStudStaff] were taken off, and they placed in a circle formed by a great number of Indians of both sexes, all naked, except a small covering of foliage about their middle, which decently covered the distinction of sexes. This local covering of several of the females was composed of beautiful flowers. The unhappy captives flood amidst this assembly a considerable time, whilst a venerable old man seemed to address them in a pathetic manner, for tears accompanied his words. He was, as my father afterwards learned, their king, 11 and of a very numerous people; and the purport of his long speech was this:

"Men, for I see you have legs, arms, and heads

as we have, look to the sunfirstfirst

The Indigenous king is the first character in the book to speak, giving him a voice not

just literally, but metaphorically. Adding further weight to his words is the power he

wields to order execution, as he threatens to do. Winkfield's choice to make this the

first line of spoken dialogue in the book lends the king power and respect, and it may

appear to foreshadow the centering of Indigenous voices as the story unfolds. At the

same time, there is an element of ableism,

as the king makes worship contingent on having limbs. - [UOStudStaff],"

here he pointed up to that luminary, "he is our god, is he yours?sun

sunAncient Israel was surrounded by peoples who worshiped solar deities.

Abrahamic religions thus condemn solar cults and other forms of animism,

viewing nature-worship as a form of idolatry. (See Deuteronomy 4.19, 17.3). The narrator equates the Indigenous

people’s religious practices with the enemies of ancient Israel, a

connection that is explicit in Chapter XI when she compares island natives

to the prophets of Baal.

Biblical passages quoted by the narrator do not

perfectly match the wording of any English translation. Here and throughout,

we have chosen to link to the King James Version, which was the official

Anglican Bible in the eighteenth century. - [UOStudStaff] He made us, he warms us, he

lights us, he makes our corn and

grass to growcreation. creationAllusion to Psalm 104.14, probably to further underscore that they mistakenly

worship the creation instead of the creator. - [UOStudStaff], we love and praise him;

did he make you? Did he send you to punish us? if he did, we will die, here are

our bows and arrows, kill us." Saying this, they all threw their bows and arrows

within the circle, between themselves and the captives. Not then knowing their

meaning, they stood silent; the king then continued his speech, "Our god is not

12 angry; the evil being who made you

has sent you into our land to kill us; we know you not, and have never offended

you; why then have you taken possesion of our lands, ate our fruits, and made

our countrymen prisoners? Had you no lands of your own? Why did you not ask? we

would have given you some. Speak." It seems they had no idea that there are more

languages than one; therefore taking their silence for a confession of guilt,

their king proceeded, "You designed to kill us, but we hurt no man who has not

first offended us; our god has given you into our hands, and you must die."

This said, the Indians took up their bows and, arrows, whilst others bound 13 my father and his five unhappy countrymen, and cut off the heads of the latter, one after another. My father expected the same fate; but just as the executioner was about to give the stroke, a maiden, who stood by the king, and whose neck, breast, and arms, were curiously adorned with jewels, diamonds, and solid pieces of gold and silver, and who was one of the king's daughters, stroked my father with a wand. This was the signal for deliverance; he was immediately unbound, and a covering, like that the Indians wore, was put round his body, and a kind of chain, formed of long grass, round his neck, of a considerable length, one end of which the princess took hold of, and gently led him along, till she came to a bower composed of the most pleasing greens, 14 delightfully variegatedvariegated variegatedconsisting of many different types of things, markings or persons - [UOStudStaff] with the most beautiful flowers; a shady defense from the sun, which then shone with uncommon heat. Beneath, was a large collection of leaves, which covered the whole surface of the ground to a great depth; here she made him sit, none present but themselves. She seated herself by him, viewed him with great attention from head to foot, felt his face and hands, but with the greatest modesty. She then arose, and going out returned presently with a cocoa nutcoconut coconutcoconut - [UOStudStaff] shell, and drinking first, presented him the remainder of a liquor of most delicious taste, of the vinousvinous vinousderivate of wine - [UOStudStaff] kind; at the same time offering him a basket of various fruitsfruitsfruitsAhuja, author of the article "Coconut - History, Uses, and Folklore," describes the best environment that coconuts thrive in, which includes "free-draining aerated soil often found on sandy beaches, a supply of fresh groundwater, humid atmosphere, and temperatures between 27°C and 30°C" (221). Given that the characters are in Virginia, a climate unsupportive of growing such fruits, Indigenous people would be unlikely to have access to the coconut during this time period. The action is also set during the first attempt of the English to make a settlement in the area. Later, tropical plant species like the coconut palm would become an important part of the colonial fruit hierarchy. To have tropical fruits imported from Caribbean islands to colonies like Virginia was considered a luxury and a way to show off wealth and status. - [UOStudStaff]. My father freely accepted of both, and found himself surprizingly refreshed. She then made a sign to him to lie 15 down, and with looks of ineffable tenderness, retired; having first laid her bow and quiver filled with arrows by him, and fastened the door of the bower with a twig.

This tender and extraordinary treatment had so far composed my father's mind, that, joined with the excessive heat of the day, and the wine together, he was so much overcome, that he insensibly fell asleep, amidst his reflections on this strange adventure. When he awoke, he found two Indian slaves fanning and defending him from the flies; which in that country are very hurtful. No sooner did they perceive he was awake, but one of his attendants withdrew, and presently returned, I cannot say with his fair, but with his black deliverer, who, smiling, gently pulled him by his chain, and led him, now willing and fearless, to a neighbouring16 [page breaks after 'neigh-'] cabin, greatly distinguished from those about it, both by its largeness and elegance.

Here he again saw the king, before whom he bowed; whilst his patroness presented the end of the chain she held to her father, who with much seeming affability returned it to his daughter. By this act my father understood he gave him as a captive to his daughter, who, immediately breaking the chain from around his neck, threw it at his feet, making a motion to him that he should set his foot upon it, which he having done, she clapt her hands, and cried out, Hala pana chi nu, language languageDespite Unca Eliza’s many references to her ability to comprehend and speak a multitude of languages of American natives, this is the only instance in Vol. 1 where the author provides a written version of a “native phrase”. However, this is most likely a fabrication. In "Realism and the Unreal in The Female American" (2011), McMurran points to the presence of "chi" and "nu", the written pronunciation of Greek letters, as evidence for this. - [UOStudStaff] "great peace be to you."

Though my father did not then understand her words, he could not but 17conceive her actions as declarative of his liberty; for actions are a kind of universal language: he therefore threw himself at her feet, when she in return offered him her hand to rise, and then led him into another cabin, completely furnished after the Indian manner. Here he found the two Indian slaves who had attended him in the bower: these the princess presented to him, and whom by the homage they paid him, he understood he was to consider as his slaves. His cloaths which had been taken from him, together with those of his less happy companions, were brought to him.

The princess continued some hours with him, and they participated of a collation of fruits, whilst the princess continually talked to him, as if he had 18understood her language. This agreeable society continued several weeks, she visiting him every day, shewingshewing shewingshowing - [UOStudStaff] him the neighbouring fountains, woods, and walks, and every thing that could amuse. At last my father began to understand her language, which redoubled all her past pleasures, when, according to the simplicity of the uncorrupted IndiansprimitivismprimitivismThis sentence reflects the concept of primitivism: “A preference for the supposedly free and contented existence found in a ‘primitive’ way of life as opposed to the artificialities of urban civilization” ( Oxford Reference). Primitivism celebrated the perceived simplicity and purity of Indigenous cultures while upholding colonists' belief that their culture was much more advanced than others. Seeing Indigenous people as primitive also agreed with the religious movement of the Puritans, who believed they could reverse the corruption of the English church by Catholic influences: “Sermons emphasize renewal, regeneration, and the recovery of a lost, primitive, edenic purity” ( Hutchins, Inventing Eden, 180). - [UOStudStaff], she declared that love for him, which he had long before understood by her actions.

Though a complexion so different, as that of the princess from an European, cannot but at first disgust, yet by degrees my father grew insensible to the difference, and in other respects her person was not inferior to that of the greatest European beauty; but what 19was more, her understanding was uncommonly great, pleasantly lively, and wonderfully comprehensive, even of subjects unknown to her, till informed of them by my father, who took extraordinary pains to instruct her; for now he loved in his turn: and sure he must have had a heart strangely insensible if such great kindness, joined with such perfections, had not had that effect.

They had now lived together six months, and understood each other tolerably, when Unca, for that was the princess's name, proposed their marriage. As she was a Pagan, though my father sincerely loved her, and wished for that union, he could not help shewing some uneasiness at the proposal20 [page breaks after 'pro-']. This the observant princess instantly saw. "What," cried she, "does not my Winka," so she called him, "love me?" My father caught her in his arms; "Yes, my dear Unca, cried he, I do, but my God will be angry if I marry you, unless you will worship him as I dopagan pagan Framed by the narrator calling her mother a “pagan,” this may be an allusion to 2 Corinthians 6.14 where first-century Christians are advised to marry other Christians instead of Greek pagans. - [UOStudStaff]." This gave birth to a long conversation, in which, though my father was a very sensible man, and had enjoyed a good education, being very young, he found it not a little difficult to teach another what he yet firmly believed himself; but as we readily believe those whom we love, he was more successful than he expected, and in a little time the princess became convinced of her errors, and her good understanding helped to forward her conversion.

21Thus love and religion agreeably divided their time; and so happy was my father with his princess, that he almost forgot his former situation, and begun to look upon the country he was in as his own, nor indeed did he ever expect to see any other again; and he now loved Unca as much as she did him, and was therefore willing to make her and her country his for ever; but an unexpected event soon gave a different turn to their affirs.

22 CHAP. II. The king's eldest daughter conceives a passion for him, which produces disagreeable consequences, from which he is delivered by Unca.MY father had never seen any other of the king's daughters since the day of his deliverance from death, but his dear Unca, till one day sitting in a wood to shelter himself from the excessive heat of the sun, the king's eldest daughter approached him. As soon as my father saw her, supposing she was one of the king's daughters, he arose to salute her with the profoundest respect. "Winca," said she, "I have long sought for such 23 an opportunity as this; let us therefore retire further into this wood, that we may converse with more freedom." My father, unsuspecting the occasion of this visit, obeyed, when the princess thus began: "Winca, it is our custom to be silent, or to speak what we think; we are of opinion that nature has given us the same right to declare our love as it has to your sex; know, Winca, then, that I have seen you, and that the oftener I have seen you the more I love you; I know my sister loves you, but I am my father's eldest daughter, and as he has no son, whoever marries me will be king after his death."

My father was so much surprized at this unexpected declaration, that he was not able immediately to reply; but as 24 soon as he was a little recovered, he endeavoured to excuse himself as well as he could, by pleading his love and prior engagement to her sister; but it was in vain: all he could say tended but to provoke her anger. At last, in a rage, not to be described, she cried, "If you will not love me, you shall die; my sister shall never enjoy an happiness that I aspire to; nor shall my vengeance be long delayed; this instant shall put a period to your life." However menacing these words were, my father was not greatly alarmed, as they were uttered by an unarmed woman, and which he conceived to be only the effect of passion, and unluckily smiled. "What! cried she, do you scorn my love, deride my power? know wretch, Alluca can despise love and death at her will."

25Saying this, she clapt her hands together, and immediately six male Indians appeared from behind the trees, where they had stood at some distance unperceived by him. "Seize that white infidel," cried she; and in an instant all power of defence or flight was equally taken from him. She then took a pomegranate-shell out of a kind of pocket that she wore by her side, and going up to a poisonous herb, squeezed the juice of it into it; then advancing to my father, "Here," said she, "be mine, or drink this; I offer you love and death; make your choice." "I can love none but Unca," replied he.

She then ordered four of the slaves to hold my father whilst the two others were about to force the poisonous 26 draught into his mouth. "Hold," cried my father, "if I must die, I will drink it myself, I cannot do too much for Unca; she gave me life, and for her sake I will lose it--I drink Unca's health; her love shall make it sweet," He drank it, and I suppose the ministers of his intended death soon left him; for not long after he awoke, as it were from sleep, and found himself in the arms of his dear Unca, when in a languid tone he uttered, "What! do I meet my dear Unca so soon in another world? this was worth dying for." He then sunk again, as into a sleep.

It seems the princess Unca, having missed my father, arrived just after her sister and the slaves had retired, and saw him sink upon the ground. As she 27 was no stranger to her sister's love for my father, her quick apprehension soon suggested what had happened; and as the Indians are remarkable for their knowledge of poisons, and no less so for their skill in antidotesscience scienceIn the seventeenth century, science was not the well-established field we know it as today, and much work in the field more closely resembled philosophy. The reference here to Indigenous knowledges about the poisonous and antidotary plants could be a recognition to the validity of this information in respect to European modes of natural philosophy. While science is not yet formalized, the natural knowledges described by the narrator comprise the types of observations that began to solidify an American scientific tradition. (Reference: Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World) - [UOStudStaff], she instantly sought, and as quickly found, an herb whose salutarysalutary salutaryhaving a good effect on somebody/something, though often seeming unpleasant - [UOStudStaff] efficacy she was well acquainted with. She immediately squeezed the juice of it into his mouth, which soon reached his stomach, and made him eject the poison; but still his eyes were closed; a second dose revived him, and opening his eyes he uttered those words to the princess, just now related. "Heaven be praised heaven-be-praisedheaven-be-praisedUnca saves William Winkfield from fatal poisoning using natural antidotes, yet she praises Heaven for his survival. The characters use nature here in a practical way but involve religion in a moral/philosophical sense. In “Curiosity and the Occult,” Barbara M. Benedict describes the complex relationship between science and religion in the context of the Royal Society, which was founded in 1660 with the goal of learning more about the natural world through scientific experimentation. Although scientists championed this experimentation as a way to better understand God’s power, other members of society “regarded it suspiciously as a usurpation of God’s role” (351), attitudes that continued into the eighteenth century as well (360). Though published in 1767, The Female Americanis set prior to the founding of the Royal Society and may reflect a fantasy of returning to a simpler time of connection between religion and nature. - [UOStudStaff]," said the princess, " my dear Winka, that I came time enough to save a life dearer to me than my own; suck more of this juice, and you will be entirely recovered."28 [page breaks after 're-'] He did so, and was soon able to get up and walk; but with a slow tottering pace, like a man whose brain has been hurt by the fumes of wine. The princess perceived his condition, and as they passed along gathered some flowers, the smell of which quickly dispelled the fumes, and fortified his brain so powerfully, that he was soon perfectly recovered, and his strength and understanding both entirely restored. Having returned the princess ten thousand thanks for thus giving him life a second time, they walked lowly homewards.

During their short walk, my father related to the princess Unca all that had passed between him and the princess Alluca, her sister. When he had 29 finished his relation, the princess replied, "I will take effectual care for your security to-night, where my sister will not be able to discover you, and to-morrow I will consult my father what further measures we shall pursue." She then led him through some bye-paths of the wood, to the hut of an honest Indian, in whom she could confide; here she left him, with a caution not to stir out till her return next day.

Early the next morning the princess Unca, and her father, came to the hut where his daughter had concealed my father. Here a consultation was begun. The king said, "He could no more blame his eldest daughter than he did his younger, for loving my father; that Alluca had conceived an affection for 30 him at the same time that Unca had, and at the instant that she touched him with her wand, Alluca was about to have done the same; that he highly condemned her intention to poison him; yet as she was tenderly beloved by him, as well as Unca, and his heir, he hoped my father would not desire him to inflict any punishment on her, since the loss of her lover would be a sufficient one." My father frankly declared that his regard for him, and his love for Unca, were sufficient motives to induce him to forgive her. The king then proposed that, to prevent all future danger, my father and the princess should be immediately married; and that they should both set out instantly for the place of my father's abode, and that, on his account, he would enter into a treaty 31 of friendship with his countrymen; and added, that he would give him a portion worthy of a princess.

As my father considered marriage as a civil, as well as a religious, ceremonymarriage marriage The author’s discourse on marriage may be a response to Daniel Defoe’s Religious Courtship (1722). Puritan dissention toward liturgical practices meant that matrimonial ceremonies were modest, private engagements in the presence of a minister. Although its ritual was informal, marriage was regarded as the cornerstone of civic development through family building. This scene could perhaps be read as pushing Puritan logic ad absurdum: if a minister is merely witness to the marital vows, any kind of witness would do. Anglican matrimony, by contrast, would be facilitated publicly by a priest according to the ceremony prescribed in The Book of Common Prayer. This also might be read as the set-up to a joke mocking Puritans, completed in a few paragraphs. - [UOStudStaff], and found, by their discourse, that their matrimonial ceremonies had nothing in them contrary to his own religion, he very readily consented. An Indian priest was sent for, and the ceremony was soon performed. A proper cabin, or hut, was immediately prepared for the reception of the new-married couple, and they were securely guarded, to prevent further mischief, till such time as the necessary preparations were made for my father's return, with his bride, to his own plantation. In a few days, every thing was ready for their departure.32 [page breaks after 'de-'] They took an affectionate leave of the old king, and got into a canoe provided for them, attended by several others, in which were several Indian maidens to attend Unca, and men slaves for my father, and a considerable baggage, the contents of which my father was then unacquainted with. Taking the advantage of wind and tide, they in a few hours arrived, without any accident, within a small distance of my father's plantation, to which he was heartily welcomed by his neighbours, who never expected to see him again. They were greatly surprised at his extraordinary adventure, and very glad that it proved the means of a friendship between them and the Indians.

33My father being again settled with his dear Unca, in his own habitation, they were now married, according to the rights of the church of Englandceremony ceremonyHere the joke, “My father considered marriage as a civil, as well as a religious, ceremony” comes full circle. The first matrimonial service in the presence of Unca’s kin was “civil.” The second matrimonial service—the legitimate one for the Church of England—is the “religious” one. The joke is that if civil and religious categories of marriage are distinct, two ceremonies might be appropriate. - [UOStudStaff], by an English chaplain belonging to one of the men of war that then lay in the harbour. Now they began to examine tha017e presents that the king had made them, and found them to be very valuable, consisting of a great quantity of gold dust and precious stones, and many curiosities peculiar to the Indianswealth wealthThe references herein offer an interesting muddling of natural and colonial forms of wealth that the author uses to describe her legacy from the Americas as well as a participation in several now-centuries old tropes describing indigenous Americans. The references to Eliza’s mother wearing diamonds and the “gold dust and precious stones” are not consistent with known mineral wealth that could have been acquired in Virginia at this time. The author could be engaging with literary propaganda about forms of wealth associated with the Indigenous stemming as far back as 1605. See Beeman’s "Labor Forces and Race Relations: A Comparative View of the Colonization of Brazil and Virginia" (1971). - [UOStudStaff]. However, my father thought it prudent to conceal the greater part of his riches from the knowledge of his neighbours, not knowing how strong a temptation a display of them might prove, as many of the colony were not only persons of desperate fortunes, but most of them 34 such whose crimes had rendered them obnoxious in their native country.

As my father had persuaded his wife to conform to the European dress, he provided for her as well as he could, till he had an opportunity of procuring cloaths more suitable to her dignity. He took every opportunity that offered to send part of his riches over to England privately, to be there disposed of, and such goods in return to be sent as he wanted; for it seems he had no inclination to leave his habitation, and the thoughts of it were highly disgusting to the princess: but had his own desires been ever so much for a removal, he would have sacrificed them to those of the princess, whom he passionately loved.

35My father built him a more elegant house, which was suitably furnished, and his plantation by far the best and largest of any about him. This was a work of time. In the interim, my mother, proving with child from the night of their marriage, was safely delivered of me. I was, a month after, baptized by the name of Unca Eliza. The king, my grand-father, frequently sent a messenger to inquire after his children, who always attended with some present of fruit, flowers, or something more valuable. Thus happily did my father and mother live together, till I was about six years old; during which time they never heard the least news about their sister Alluca: but at this period an Indian brought 36 the news of the old king's death, and that Alluca, still single, was received as queen.

A little after, as my father and mother were sitting in the garden, and I playing at their feet, a slave informed them that two Indians were come from the princess Alluca. As soon as they came into the garden my father was surprised to see that they had each of them a great coat on, contrary to the Indian custom: he had scarce made this reflection before one of them, being come close up to him, pulled a short dagger out of his sleeve, and made a push at him, which most probably would have proved mortal, had not he, by a sudden motion, avoided it. At the same instant my mother gave a loud 37 shriek, when my father, turning his eyes, saw her falling with a dagger in her breast, for the other assassin had been too successful in his murderous attempt. My father caught her in his arms, and received her dying blood and breath together. The slaves, that my mother's shrieks and my cries had brought to us, presently seized the two murderers. One of them, who dearly loved my mother, drew the dagger out of her breast, and plunged it into the heart of him who had assassinated my mother, and was going to have done the same by the other, when my father cried out, as loud as he was able, " Take him alive." He was instantly bound hand and foot, and carried to a place of security.

38What is human felicity? How often our greatest pleasures procure us the greatest misery! This moment behold a happy couple mutually endearing themselves to each other, whilst the infant offspring of their loves beholds their joys, partakes of, and adds to them. The next--but let the scene sink into darkness! 'tis too affecting for a daughter's pen to draw.

39 CHAP. III. Death of the Indian queen; Unca and her father embark for England; provides for his brother; a description of the person and dress of the female American; her father returns to Virginia; for which she afterwards sails, where her father dies.AS soon as my mother was buried, and my father a little composed, he called for the surviving assassin, and from him learnt that the princess Alluca had compelled him and his companion to be the instruments of her revenge on them, for his having slighted her love loveloveWinkfield characterizes Alluca as villainous and violent because Unca Eliza’s father "slighted her love." Winkfield writes a powerful woman of color but with a stereotypical motive that has been exhausted in the media: romantic or sexual jealousy. This stereotype can be related to the common trope found in literature and film of the "Jezebel," defined as a sexually deviant woman of color with little characterization other than love or lust. Harmful stereotypes of women of color in media such as The Female American can lead to negative perceptions in the real world. Additionally, this negative characterization of Alluca lends additional support to the growing scholarly consensus that Winkfield was not a woman of color. - [UOStudStaff]. My father consulted 40 with the rest of the planters, whether they should deliver the assassin up to justice, or let him go home. Considering the infant state of the colony, and the temper of the reigning princess, they thought it prudent to avoid every thing that might occasion a quarrel with the Indiansquarrel quarrelThe unwillingness to disrupt the tenuous relations between the indigenous peoples of North America and Europeans may also be a reference to a series of conflicts occurring in the ten years before the original publication of the novel leading into the Seven Years War. Confederations of indigenous peoples fought for and supported on both sides. - [UOStudStaff], and therefore agreed to give their prisoner his liberty. At his departure, my father charged the slave to tell his queen, that her God, the sun, had seen the murder she had commanded, and would revenge it.

It was not long after before my aunt the queen died of grief. A little before her death, she ordered, that after her decease her heart should be sent to my father with this message: "Receive a heart that, whilst it lived, 41 loved you, and had you received it, it had never been wicked. Forgive my revenge, and let my heart be buried with you when you are dead; but may the sun give you many days!" This was accompanied with a very great present of gold dust, and her bow and arrows, of exquisite workmanship, for me. The bow, and some of the arrows, I still have.

This renewed my father's grief, which had indeed but little subsided; therefore to divert his sorrows, and give me a better education, he determined to return to England. Every thing was accordingly prepared. I was about seven years old when we embarked, attended by several male and female slaves. We had a tolerable passage 42 to England, and found my father's brother in good health. He was, as I before observed, a clergyman, and had a living in Surry, where he constantly resided, had a wife, one son, and three daughters, the youngest of them elder than me. He was exceedingly glad to see his brother, and received me as if I had been a child of his own. He was an excellent divine, of great piety, and of uncommon learning, but ill provided for in the church. As my father was very rich, he gave him five hundred pounds for each of his children, and soon after bought the next presentation to a living of three hundred a year. The incumbent dying soon after, he presented my uncle to it, with a thousand pounds to pay the expence of removing, as he 43 said when he gave it. This occasioned our removal to a pleasant village near Windsor.

If I was kindly entertained by my uncle, I was little less caressed by the neighbours. My tawny complexioncomplexioncomplexionThe narrator claims to be of Indigenous descent, but Emelia Abbé discusses the ways in which this novel actually plays on the exploitation of Indigenous peoples through the lens of the colonial British perspective. - [UOStudStaff], and the oddity of my dress, attracted every one's attention, for my mother used to dress me in a kind of mixed habit, neither perfectly in the Indian, nor yet in the European tastehabit habit The “mixed habit” of Unca Eliza’s dress may reflect her identity as a biracial woman in eighteenth-century England. Unca Eliza recognizes herself as “neither perfectly” European nor Indigenous. She is brought up in English society but is othered by the community around her for her Indigenous identity. In “Models of Morality,” Victoria Barnett-Wood connects The Female Americanto the Bildungsroman genre. Similar to modern “coming-of-age” stories, the Bildungsroman centers around the growth of a character and their understanding of the world. In this context, Unca Eliza’s attention to her otherness can be viewed as an early development in her understanding and critique of the imperial world. - [UOStudStaff], either of fine white linen, or a rich silk. I never wore a cap; but my lank black hair was adorned with diamonds and flowers. In the winter I wore a kind of loose mantle or cloak, which I used occasionally to wear on one shoulder, or to cast it behind me in folds, tied in the middle with a ribbandribband ribbandribbon - [UOStudStaff], which 44 gave it a pleasing kind of romantic air. My arms were also adorned with strings of diamonds, and one of the same kind surrounded my waist. I frequently diverted myself with wearing the bow and arrow the queen my aunt left me, and was so dexterous a shooter, that, when very young, I could shoot a bird on the wing.

My uncommon complexion, singular dress, and the grand manner in which I appeared, always attended by two female and two male slaves, could not fail of making me much taken notice of. I was accordingly invited by all the neighbouring gentry, who treated me in a degree little inferior to that of a princess, as I was always called; and indeed I might have been a queen, 45 if my father had pleased, for on the death of my aunt, the Indians made a formal tender of the crown to me; but I declined it.

My uncle, who gave his daughters the same learned education with his son, desired I might make one of their society. This was very agreeable to my father, and no less so to me, who was very fond of my cousins, and willing to do what they did. I could already speak the Indian language as well as English, or rather with more fluency.

In this manner we lived near a year, happy I should say all of us, but my father, who, as he had no business to do, grew more melancholy: he therefore resolved to revisit the country 46 where he had left the remains of his princess. It was in vain to intreat his stay, my uncle and aunt's remonstrancesremonstrances remonstrancesprotests or complaints - [UOStudStaff] were lost, and only served to confirm his resolution of returning to his plantation. However, he thought proper to leave me with my uncle, to complete my education. Though I was unwilling to part with my father, I was as much so to leave my cousins, and therefore staid behind pretty contentedly. My father, before his departure, made great preparations for the improvement of his plantation, rather for his amusement, than from a desire of gain.

I continued here till I was eighteen years of age; during which time I made a great progress in the Greek 47 and Latin languages, and other polite literature; whilst my good aunt took care of the female part of my educationeducationeducationAt this time, it was standard for women to receive a different level of education from their male counterparts. Whereas men belonged in the public sphere, women's lives were centered on home life and the care and early education of children. In his influential work Émile, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) argues that any education of women beyond housework should aim to “make them more effective and stimulating companions for their husbands,” and only that (see An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age: Education).Michèle Cohen argues that the limiting of the female curriculum was “not to meet the needs of femininity so much as to produce femininity” (322). A proto-feminist critic of this system, Mary Astell (1666-1731), protested as early as 1694 that women were being bred deliberately in “ignorance and vanity” (A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, 31). The emphasis here on the female education and its difference from that of men gives interesting insight into the role of women during this time period. - [UOStudStaff] with equal success. Tawny as I was, with my lank black hair, I yet had my admirers, or such they pretended to be; though perhaps my fortune tempted them more than my person, at least I thought so, and accordingly diverted myself at their expence; for none touched my heart.

Young as I was, I often thought on my dear mother, and honoured her memory with many tears. And as I found it was the custom in England to erect monuments for persons who often were interred elsewhere, I desired my uncle to erect a superb mausoleum in his church-yard, sacred to 48 the memory of my dear mother. It is a lofty building, supported by Indians as big as life, ornamented with coronets, and other regalia, suitable to her dignity. The form is triangular, and on one side is cut an inscription in the Indian language, containing a short account of her life and death. This I drew up and translated into Latin and English, which fills up the two other sides; on the top is an urn, on which an Indian leans, and looks on it in a mournful posture. The whole is surrounded with iron pallisadoespalisades palisadesPalisades are fences made of strong wooden or metal posts that are pointed at the top, typically used in the past to protect a building. - [UOStudStaff]. This I often visited, and here I dropt many a tear.

My father, by this time, begun to think my absence long, and desired my return, which was equally agreeable49 [page breaks after 'agree-'] to me; for though I was pleased with my situation, and the affectionate treatment of my relations, yet I secretly longed to see my native country, of which I retained a perfect idea, but more so to see my father. Every thing being prepared for my voyage, I, with my four slaves, embarked on board a ship for my return home, being then in my eighteenth year. However, my uncle insisted that his son John Winkfield, my cousin, should go with me to take care of me. His regard for me, and desire to see a strange country, made him very glad to accept of the proposal.

During our voyage, my cousin neglected no opportunity to renew his addresses to me, which he had before 50 begun in England. I gravely told him I would never marry any man who could not use a bow and arrow as well as I could ; but as he still continued his suit, I always laughed at him, and answered in the Indian language, of which he was entirely ignorant; and so by degrees wearied him into silence on that head.

I shall not trouble my readers with any particulars of our voyage, and shall only say, that after a tedious and indifferent one, I once more found myself in the embraces of a tender father. The fight of me revived in his memory the remembrance of my dear mother, which drew from him a flood of tears, with which I sincerely joined mine. As soon as these subsided,51 [page breaks after 'sub-'] his transports of joy were as great to see me returned in safety, and to much improved. He received my cousin with great affecion, and, on his return home, gave him a bill on England for one thousand pound sterling; which he might well do, for he was extremely rich. I on my part desired some considerable presents to be sent to my uncle and aunt, and to my cousins, with some of less value to my female acquaintance; together with some natural curiosities of my own country, as birds, shells, &cetcetcet cetera - [UOStudStaff].

There was one circumstance attending my education, whilst under my uncle's tuition, that, in justice to his memory, I ought not to omit, the religious part; and in this he was as 52 methodical and exact as though I had been to be a divine; nor did he inculcateinculcate inculcateto cause somebody to learn and remember ideas, moral principles, etc., especially by repeating them often - [UOStudStaff] religion as a mere science; but in such a warm and affecting manner, that whilst his lectures convinced the understanding, they converted the heart, and made me love and know religion at the same time. The happy effectts of his pious instructions I have experienced throughout my life; and indeed in one part of it they were not only of the greatest comfort to me, but of the highest use; as will appear hereafter.

But to return to my father: neither his riches, business, nor even my company, whom he most affectionately loved, could cure him of that melancholy under which he laboured from the decease of my mother. This, at 53 length, determined him once more to visit England, that new objects might divert his mind. With this view he soon found means to remove his great wealth to England, and prepared to dispose of his plantation; but by the time he had almost done the former, and had agreed to let his plantation, he grew so bad as to be incapable of a removal, and in a few days went to that happiness in another world, which he could not enjoy in this.

54 CHAP. IV. Unca buys a sloop, and embarks for England; the captain proposes a match between her and his son; her slaves and attendants massacred, and herself left on an uninhabited island.HAVING paid my father every funeral honour I could, and having nothing now to attach me to this country, and the bulk of my great fortune lying in England, I determined to embark for that kingdom, and to conclude my days in my uncle's family. But Solomon saith, "The heart of man deviseth his way, but the Lord directeth his going:"Proverbs Proverbs Proverbs 16:9 - [UOStudStaff] and so I found it. I was now in my four and twentieth55 [page breaks after 'twen-'] year. At this time an opportunity offered that favoured my intended voyage. There was a sloop in the harbour, a good sailing vessel, and large enough to carry me, my attendants, and effects. I chose an old captain, who had lately been ship-wrecked, and lost his all, and who wanted to get over to his son in England, to undertake the care of us, and as, a gratuity for his trouble, promised, if we arrived safe in England, to give him the ship, that he might once more be able to follow his occupation.

This proposal he accepted with great joy, and having got together a sufficient number of hands to navigate our vessel, I prepared to embark. Notwithstanding what my father had before sent to 56 England, I had yet a great many valuable goods to take with me, to the amount of near ten thousand pounds. These being safely lodged on board, I followed myself, attended by my two favourite female slaves, who had sailed with me before, and six men slaves, who begged to attend me; though I had offered them their liberty, if they chose to stay behind.

We sailed with the first fair wind, and had not been on our voyage above a daysailedsailedThese details situate the island on which Unca is eventually stranded in the Pamlico Sound region. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the average commercial vessel would be able to reach speeds of five miles per hour in fair winds. Given that the ship had been sailing for less than a day, the maximum range they could have reached would be 120 miles. The most popular Virginian port during this time period was located in Norfolk, and a return journey back to England would send the ship in a backwards "J" pattern starting by going south until roughly the oceanic region off the coast of South Carolina. - [UOStudStaff] before the captain, willing to lose no time, began to talk to me very freely about marriage. He did not indeed sollicit me for himself; but he made strong courtship for his son. I at first answered him with good humour, and told him I hoped he would let me 57 see his son before I determined to have him; and that if he could shoot with my bow and arrows, which then hung by me in the cabin, as well as I could, I would have him, were he ugly or handsome. But I soon found that he was too much in earnest, and I too much in his powergender genderDespite Unca Eliza's enormous wealth, extensive education, and physical ability with weapons, she still suffers the power disadvantages associated with her gender at this time. - [UOStudStaff]: for in a peremptory manner he told me, that if I would not immediately sign a bond to marry his son, on our arrival in England, or forfeit thirty thousand pounds, I should neither see England, nor return to my plantation. I wondered he did not propose himself, but I found afterwards that he was a married man, as he informed me. I did not know law enough then, or else I might have given the bond, and so have avoided the distress that my refusal occasioned, as in 58 equity I might have been released from the penalty; and the readier, as my two female slaves were witnesses to all he said. But as I persisted in my refusal, he grew incensed, and having I suppose gained the ship's crew by promises to assist him, at last told me he was come to a resolution, that as I persisted in my refusal, he was now very opportunely coming to an uninhabited island, where he would leave me to be a prey to wild beasts; and that as I had given him my ship, he would make bold to give himself the cargo. Two of my men slaves happened to come behind him just as he said these words, when one of them caught him in his arms, and the other opening the cabin-window, threw him into the sea. I know not. whether I was sorry for this, 59 at that instant; but I soon had occasion to be heartily so, for the consequence was fatal to them. As our ship, at this time made very little way, and the captain could swim, he presently got up to the ship, and being seen by some of the crew, who knew not how he got overboard, a rope was thrown out, and he quickly drawn up. In the mean time, one of the two men slaves went, and brought the other four into my cabin. Soon after the captain, and several of his men, armed with piltols and cutlasses, came into the cabin. The captain advancing up to him who threw him overboard, shot him dead, and now a terrible skirmish began. I indeed got no hurt, which was a wonder, for though no blow was aimed at me the close of the place exposed me to 60 imminent danger; and the two female slaves got several wounds. My men slaves were unarmed, and therefore soon overcome, three were killed outright, and the others, I suppose, mortally wounded. The poor faithful fellow who opened the cabin-window was hung up alive at the yard-arm, bleeding as he was, there to perish by hunger, thirst, and heat. This touched me more than my own misfortune, I offered the captain a thousand pounds to release him, and to let him be cured of his wounds. "Madam," returned the villain, "where are your thousand pounds? all you have on board is already in my possession."-Thus could I only pity, but not relieve.

61I now expected my own destiny; and it soon arrived. The captain, who had left the cabin, to dispose of his prisoners, returned, and once more asked me if I would sign the bond? I answered, no; and at the same time desired that my two maids might have some care taken of their wounds. He replied, he had no surgeon, and if they did not grow well soon he should throw them overboard; but if they recovered, he should sell them the first opportunity: he then left the cabin. A few hours afterwards we came to an uninhabited island, where he put me on shore, for nothing that I said could soften his heart. I begged hard for both, or one, of my maids; but all the favour I could obtain, was my bow and quiver of arrows: 62 page breaks after 'ar-' indeed he gave me a box of clothes; but for these I did not thank him, as I never expected to use them, thinking myself consignedconsign consignconsign: to make over as a possession, to deliver formally or commit, to a state, fate, etc. - [UOStudStaff] to some wild beast, whose prey I should become.

63 CHAP. V. She offers up praise to God; takes refuge in an hermitagehermitage hermitagea solitary or lonely habitation, possibly the habitation of a hermit. - [UOStudStaff], where she finds a manuscript left by the deceased inhabitant, in which are intsructions how to subsist on the island; reflections on her situation.THUS disconsolate, and alone, I sat on the sea-shore. My grief was too great for my spirits to bear; I sunk in a swoonswoon swoonBoth The Female American and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) mention their main characters falling into a swoon or “fainting-fit” (Oxford English Dictionary). Crusoe faints as he braves a tremendous storm at sea, while Unca Eliza faints in instances like being stranded on an island, getting overstimulated, and thinking she sees a ghost. Crusoe faints in response to a proportionally more severe situation, which can be read as a commentary from Winkfield on the expected submissive roles of women in eighteenth-century life. Winkfield’s use of swoon contrasts the major themes of female authority and gender performance seen throughout the novel. - [UOStudStaff] on the ground: how long I lay in this senseless state I know not, or whether I might ever have recovered, had not a wave, brought on by the rising tide, and which broke over me, awaked me. I arose, hardly sensible where I was, or what I was doing, and ran to a rising ground, and here I 64 once again beheld my deplorable condition. A few minutes recollection brought me to a sense of my duty: for reflecting within my mind, that as the wicked captain could very easily have killed, or drowned me, it was a wonder that he should give me the least chance for life; that I ought therefore to thank God for this escape, and to commit myself to his providenceprovidence providencedivine direction, control, or guidance - [UOStudStaff]. Indeed, in the hour of affliction we are ready enough to pray to God for help; but are so taken up with a sense of our miseries, that we forget that we have any mercy to be thankful for. We should always sing a Te Deum before we sigh a litanyte-deum te-deumShort for Te Deum Laudamus, a traditional hymn of praise meaning, "We Praise You, O God." A litany is a prayer of supplication, or a request. - [UOStudStaff]; for our sighs will sink before they reach heaven, unless raised thither by the wind of praise.

65Filled with these ideas I fell on my knees, and thanked God, who had delivered me out of the hand of the wicked, and that now I was in his only. On this occasion, these words of David came into my mind; "Let me now fall into the hand of the Lord, for his mercies are great, and let me not fall into the hands of man."allusions allusionsA reference to both 2 Samuel 24.14 and 1 Chronicles 21.13 where David, the king of Israel, decides to take a census and build a temple. Winkfield’s comparison between her situation and that of King David’s may perform a sort of epic simile to mark the establishment of her religious authority on the island. - [UOStudStaff]At the close of my prayers, I solemnly committed myself into the hands of God. I now arose from my knees with a serenity by no means to have been expected. During this composure of mind, I advanced to the highest ground I could see, in hopes I might discover some place of safety, not considering the improbability of such a discovery. Though the sun shone very hot, which soon dried my wet clothes, yet I saw it 66declining apaceapace apaceat a considerable or good pace - [UOStudStaff]; I therefore kept looking about with eager expectation, when at last I saw, or thought I did, the ruins of a building. I advanced and saw it more distinctly: though it promised what I wished for, an asylumasylum asyluma place of refuge, shelter, or retreat - [UOStudStaff], yet I dreaded to go nearer. I looked, I stopped, I prayed, and then I moved again; thus strangely divided between hope and fear, I still kept going forward, and in an inexpressible agitation got close up to it, almost insensibly.

I was so near now as to perceive a door half open: I listened and heard no noise. Fearful to retire, or to enter, I stood trembling a long time. How long I might have remained in this condition I know not, had not a sudden noise behind me, like the hallooing of 67 a human voice, forced me precipitatelyprecipitately precipitatelyhastily, rashly - [UOStudStaff] to rush in, fearless of the danger within, that I might avoid that which threatened me from without. This double sense of danger deprived me of my senses, and I sunk down in a swoonswoon. As I recovered by degrees, I saw all within the apartment before I was quite sensible enough to be afraid of my situation, and seeing nothing to alarm, I grew quite calm, and observing a kind of great chair, formed of several large and less stones, and the seat covered with a great heap of leaves, I sat down, and rested my weary limbs and agitated spirits.

The sun still shone pretty bright through the holes in the wall, which was of stone, and perfectly discovered 68 every thing within. My fright had deprived me of the thought to shut the door: however, nothing came to hurt or alarm me. Before me was an heap of stones, on which laid a greater, which served as a table, and near enough to lean on. In a large fish-shell that lay on the table I perceived water, which I boldly ventured to drink of, and found myself instantly refreshed. I lifted upmy heart to heaven, with thanks, and bespokebespoke bespokerequested, asked for - [UOStudStaff] its further protection. On my right hand I saw a kind of couch formed, like the table, of a heap of stones, and the flat part, or surface, covered with moss and leaves. I now concluded that this was the habitation of some human being: but this gave me no alarm; for as I had read of hermitshermit hermitpeople who choose to live a solitary life for religious reasons - [UOStudStaff], who frequently retire from public life 69 to enjoy their devotions in private, I imagined, from what I saw, that this must be the habitation of such a one, from whom I did not doubt but I should meet with protection and spiritual consolation.

This reflection restored me to such tranquility of mind, that I rested myself with the pleasing expectation of his return, which, considering it was near night, I thought could not be long. As I had now fresh cause to be thankful, I was so; and found I had spirits enough to sing a short Latin hymn of praise. But still no hermit appeared, and the sun was now set; but the moon was risen, and shone with so much brightness into the cell, that I scarcely missed the greater luminary. As I thus sat waiting,70 [page breaks after 'wait-'] I observed a book lying on the table, which I had not before perceived, which I supposed to be a book of devotion; but on opening it, found it to be a manuscript, in the first leaf of which were these words.

"If this book should ever fall into the hands of any person, it is to inform him that I lived on this uninhabited island forty years; but now, finding the symptoms of death upon me, I am going to retire to another stone room, where I shall lay me down, and, if God pleases, rest for ever from all my troubles."

As this was dated, as to the month and year, tho' without day of the month, I concluded he must be dead, as it was a month ago, and therefore gave over 71 all expectation of seeing the hermit, with the thought of whose presence I had pleased myself. A little lower, in the same page, was added, "If thou shouldest be obligedobliged obligedunder a necessity - [UOStudStaff] to stay here any time, there are no wild beasts or noxiousnoxious noxiouspoisonous or harmful - [UOStudStaff] animals to injure thee; nor savages, except once a year, on one day, see page of this book, 397. How you may subsist, you may learn from the history of my life."

I immediately turned to the page referred to, and found that it was yet two months to the time of the Indians coming on this island. I now thought I might sleep securely; I therefore shut the door, and fastened it with a heavy stone that lay there, I supposed for that use. Coming back from the door I spied 72 an heap of Indian rootsroots rootsThe "Indian roots" referenced here are almost certainly cassava (also called yucca or manioc), a large tuber that was originally domesticated in what is today Brazil, and remains a global staple today. Cassava must be heavily processed to get rid of the deadly amounts of prussic acid the raw root contains. Processing techniques include fermenting, roasting, boiling, and more. Cassava has long been made into flour and bread. See Mark H. Zanger, "Cassava," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. - [UOStudStaff], which I presently knew to be such, and which serve instead of bread. As some of them were yet very good, and had been roasted, being very hungry, I ate heartily, and drank more of the water. As I walked about the room I saw in a nook another shell, which I imagined to be filled with the juice of wild grapes, from the look and taste, and therefore, as I was faint, drank some of it, but with caution, as I found it was grown strong with standing. As the moon still shone very bright, I took out my Greek Testament, which I always carried in my pocket, it being my custom to read a chapter in it morning and night. I opened accidentally in the epistleepistle epistleA letter, usually of public or formal nature. Many books in the New Testament are epistles. - [UOStudStaff] to the Hebrews, and the first words that offered to my view were 73 these: chap. xiii. 5. Οὐ μή σε ἀνῶ ουδ’ οὐμήσε ἐνκαταλίπω. Hebrews HebrewsCorrect spelling should read, Οὐ μή σε ἀνῶ οὐδ’ οὐ μή σε ἐγκαταλίπω, which the King James Version of the Bible translates, “I will never leave thee, nor forsake thee” (Hebrews 13.5). - [UOStudStaff] I cannot but say they gave me great comfort, and I thought myself, in that moment, equal to all the difficulties I foresaw I had to encounter with, through the divine protection: though I very well remembered the caution my pious and judicious uncle gave me. "Beware," said he, "of the practice of some enthusiasts of our times, who make the word of God literally an oracleoracle oraclethe instrument, agency, or medium through which the gods were supposed to speak or prophesy - [UOStudStaff], by opening of it at particular times, and on particular occasions, presuming that where-ever they open, they are to apply the passage to themselves, or to the business they are about; because many have thereby been led into spiritual pride, and others into despair, as they opened on a promise, or 74a curse; whilst others have but too often, in the same manner, pleaded a warrant from scripture to perpetrate wickedness, or to propagate error. Though," added he, "happy is the christian who by a prudent and rational use of the scriptures procures comfort to his soul. For as the apostle says, Whatsoever things were written aforetime, were written for our learning, that we through patience and comfort of the scriptures, might have hope." Rom. ch. xv. v. 4.

Having read the whole chapter, and said my prayers, I prepared to take my rest on the stone couch, and laid down in my clothes, with more composure, notwithstanding my dreadful situation, than my wicked captain, I think, could 75do, though indeed, I believe, a man may sin to such a degree, as to render his conscience quite callous; the most dreadful state a human being can sink into. Sleep soon closed my eyes, and I did not awake till the sun was up. My spirits cheered by such timely refreshment, and my devotions performed, I quitted my cell, and directed my feet towards the sea-shore, to see what was become of my chest that I had left there the preceding night; little expecting to see it again, because I thought the working of the tide must have washed it into the sea, or have buried it in the sands. After some search, I spied it almost buried indeed in the sands, but was not much better for the discovery, as I was unable to remove it. I therefore returned to my cell, ate 76some of the Indian roots, and drank a little water, whilst my mind was busied, how I should break open my chest, and so bring away at times what I could not at once. I had indeed a small knife in my pocket, but that was not strong enough to cut through a thick board. I looked round my cell, but found nothing that could assist me. This gave me some concern, for if I could not come at my clothes, I considered that I should soon be very uneasy to myself, and started at the thoughts of going naked; however, for the present, I was obliged to be contented.

But now other cares came into my mind. The roots I fed on were not all of them good, but only a few of them 77so; and how was I to get more? I did suppose they grew in the island; but I was not fond of rambling. Though the hermit's manuscript assured me there were no inhabitants nor animals to hurt me, yet the thought of wandering alone was terrifying. I might lose my way, and not be able to find my cell again, or not under a long time; and even should I find plants near my habitation, how was I to make a fire to roast them? Other anxious thoughts still pressed upon my mind one after another. At last, I recollected, that in the memorandum I had read the night before, I was informed, that the hermit's manuscript contained instructions how to subsist. This once more cheered my mind; and I now began to give it a careful reading, but not regularly; 78impatiently looking here and there for those things that most concerned me. It was written in a fair legible hand. I soon found that there was a flint and steel in the cell I was in; that at some distance there was a small river that ran quite through the island; that he made use of the shell of a certain fish for a lamp, in which he burned the fat of goats, and for a wick made use of a particular reed. I then searched to learn how he got goats to supply himself with fat, and, at last, met with this memorandum: "When I first came upon this island, I found plenty of goats, yet having no fire-arms, I was never the better for the discovery, as they were too wild to catch. But observing that they were very fond of a yellow fruit that grows 79on several of the trees here, and that they were continually watching when any of it fell off to eat it, this suggested a thought, that if I gathered some of it, I might possibly tame them by giving them plenty of it to eat. I accordingly broke down some of the branches, and whilst I held them in my hand, they would follow me up and down like a dog, so that I could catch them when I pleased. I found also that the goats, if I laid plenty of this fruit before them, would let me milk them whilst they fed. I from this time, no more wanted either milk or goats flesh. But as I knew this fruit would not be on the trees all the year, I gathered large quantities of it in the season, and 80saved them to serve in the other part of the year."

This information gave me great pleasure; I immediately searched and found the steel and flint, and near them dry leaves and touch-wood. I now thought of setting fire to one end of my box, as thinking it better to burn part of my clothes than come at none of them: but however, I declined this method, in hopes of finding some better expedient; but was still very uneasy, lest the tide should remove it into the sea, or bury it out of sight in the sands; but I was obliged to run every risk. A few days afterwards what I wished for was effected by a means that I at first thought would have entirely deprived me of my chest. I 81was walking near the sea-side, looking at my chest, when I observed the sea to rise, and presently the winds blew very tempestuously. I retreated back enough to observe the storm in safety, which, at last, became very great, and soon saw my chest tossed about by the waves, as though it had been as light as a feather. I expected that every fresh wave would remove it for ever out of my sight; but it was removed further and further on shore, as the sea advanced, till, at last, I saw it no more. I then gave it up for lost, and returned home, for so I now called my cell, very uneasy.

However, the next day, the storm being over the night before, and the sun shining very bright, I again visited 82the shore, and the spot where the chest had lain, but in vain. But seeing at a distance higher up from the shore some rocks, my curiosity led me to go up to them, not with any expectation of finding my chest, for I had given over all thoughts of it; but climbing up one of them, I found my chest lodged there. I was glad to see it, though the same difficulty still remained, how to open it. Being weary with climbing the rock, I sat myself down to rest. As I was sitting on that side of the rock that declined to the sea, I observed that on the other side of the rock was a very deep descent, at the bottom of which were craggy stones, but level with the rest of the island. I was startled at my nearness to it; however, this suggested something to my mind. If, 83thought I, I could push the chest down this precipice, the fall might break it; at least, it would be out of the reach of the sea. However, I was afraid to do so, lest I should tumble over with it. But after some consideration, I thought that if I laid myself down on the ground, on the side on which I got up, I might attempt it.. I accordingly tried, and with great, difficulty moved it, but not immediately; at last, after a great deal of labour, it fell over. The noise it made, when it came to the ground frightened me, though I knew what it wasnoisenoiseUnca Eliza is affected by the noise made by the falling chest, despite knowing its source (herself). As Samson et al. explain, “noise is one of the most widespread sources of environmental stress in living environments." The physiological stress response is a "split-second" reaction, whereas the recognition that there is a lack of immediate danger is a slower comedown. Paula McDowell explains in her book, The Invention of the Oral: Print Commerce and Fugitive Voices in Eighteenth- Century Britain, how “the consumption of sound is at once physiological and psychological” and that “social and personal factors influence not only what we hear but what it means.” The recognition that she is the source of the noise changes the psychological meaning of the sound for Unca Eliza, despite experiencing the natural physiological response. - [UOStudStaff]. My next business was to get down the way I came up, and then to find my way to the valley. I did so, but was obliged to go a great deal about. When I was come near to the spot, I found the ground so rugged 84 that it was with great difficulty, and not without several falls, that I reached the chest, which I found broke into a great many pieces, and it took me up near a whole day to remove the contents; gowns, linen, and many other useful things. All these I conveyed to my cell; not a little pleased that I had, at last, conquered this difficulty, and was now supplied with things that I should have greatly wanted.

But to return to where I left off: having found the steel and flint, I immediately made a trial of them, and they were in very good order. I found three lamp-shells ready prepared; I lighted them, and they burnt very well. My next attempt was to get some goats milk, as I had yet tasted nothing but 85 roasted roots and water; I took a large fish-shell, of which I found plenty ready to my hand. It was not long before I met with the tree with the yellow fruit, and several goats under it, who ran a little way off as I advanced, but not out of sight, but seemed to wait as if they watched me. I found it very difficult to climb the tree; but, at last, got up and broke several boughs off: and as soon as I was down, the goats came to me; I laid the boughs down, and clapt my foot on them, lest the goats should drag them away. I now tried to milk one of them, but very aukwardlyawkwardly awkwardlyawkwardly - [UOStudStaff], having never done so before. However, I got enough to drink then, and to bring home for another time. I repeated this practice till I became very ready at it; and not 86 knowing how soon the fruit might fail, I took care to gather and save a good deal of it.