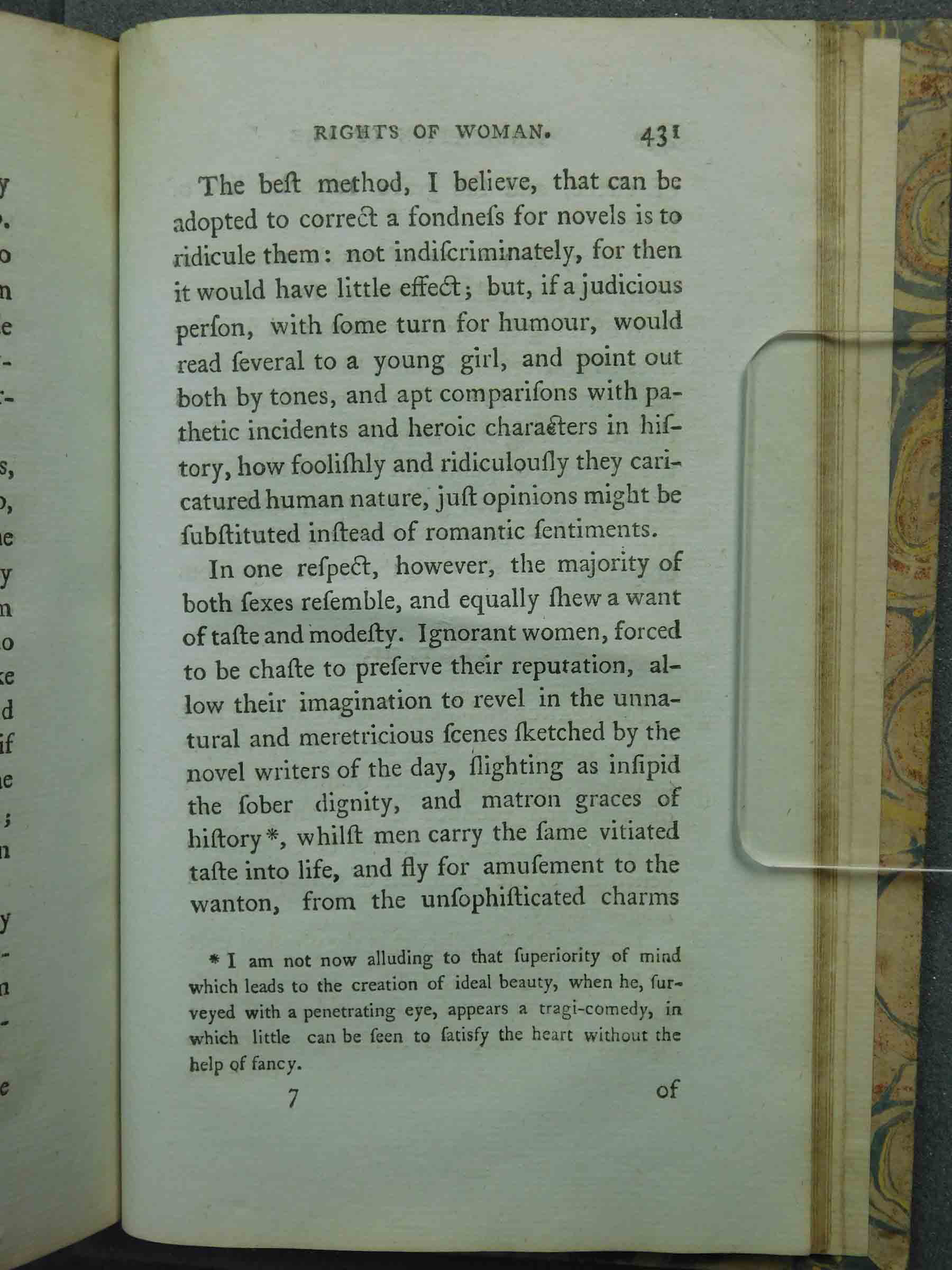

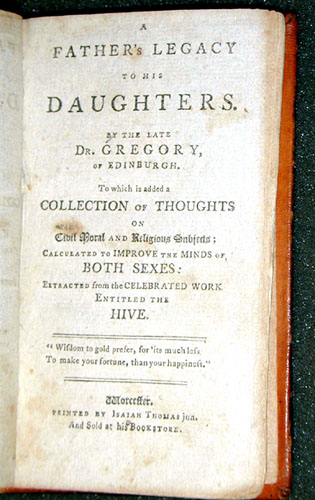

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

By

Mary Wollstonecraft

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students and Staff of Marymount University, Felix Baquedano, Nomin Bayanmunkh, Rewan Bezabih, Rosaida De Jesus, Josephine Fleming, Daryl Frierson, Tierney Goetz, Alexandra Holmes, Muna Mohamed, Sarah Moustafa, Dana Najib, Maria Robelo, Katelyn Smolar, Elizabeth Swanson, Bianca Thompson, Susana Valladares

wollstonecraft

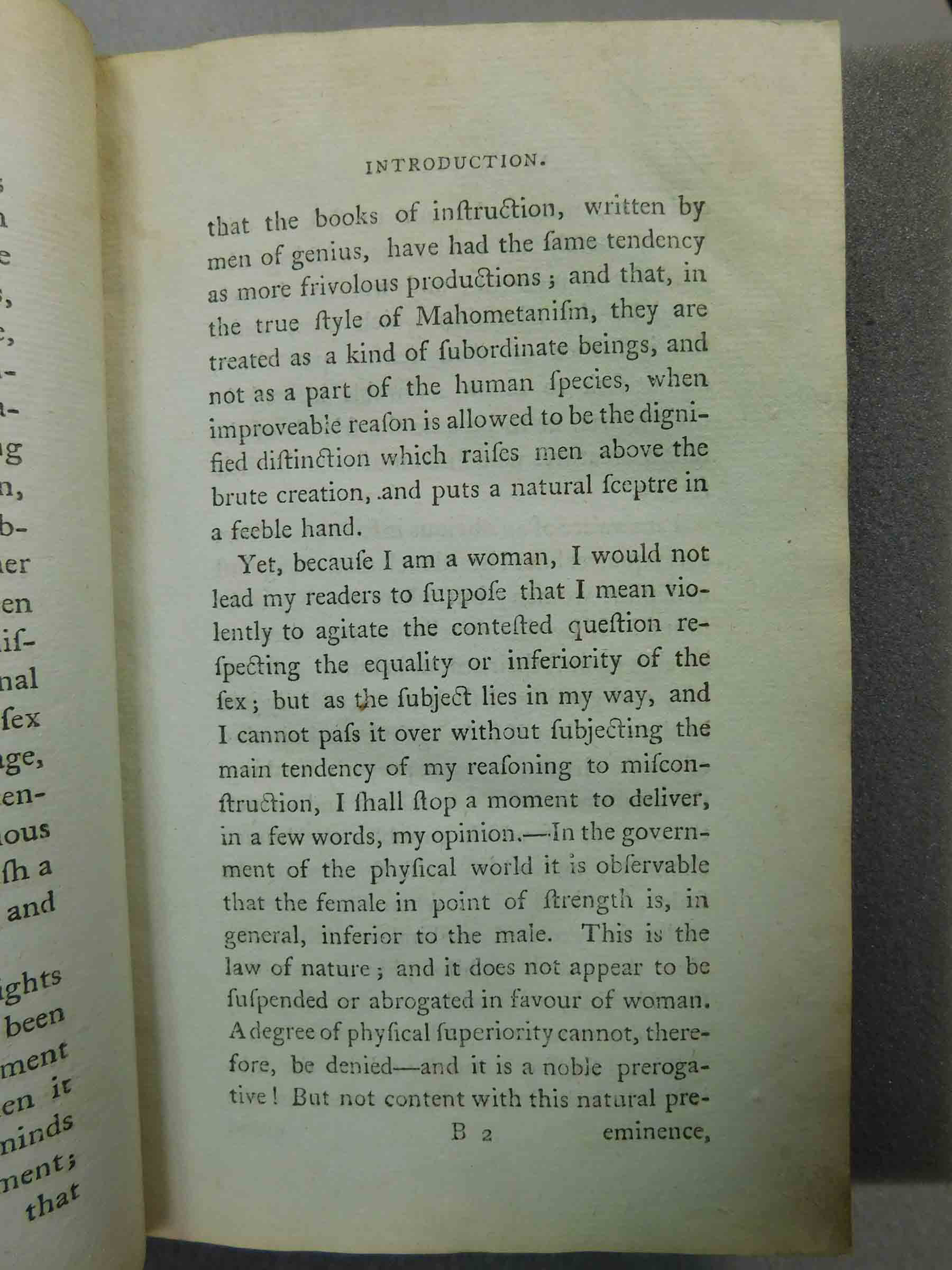

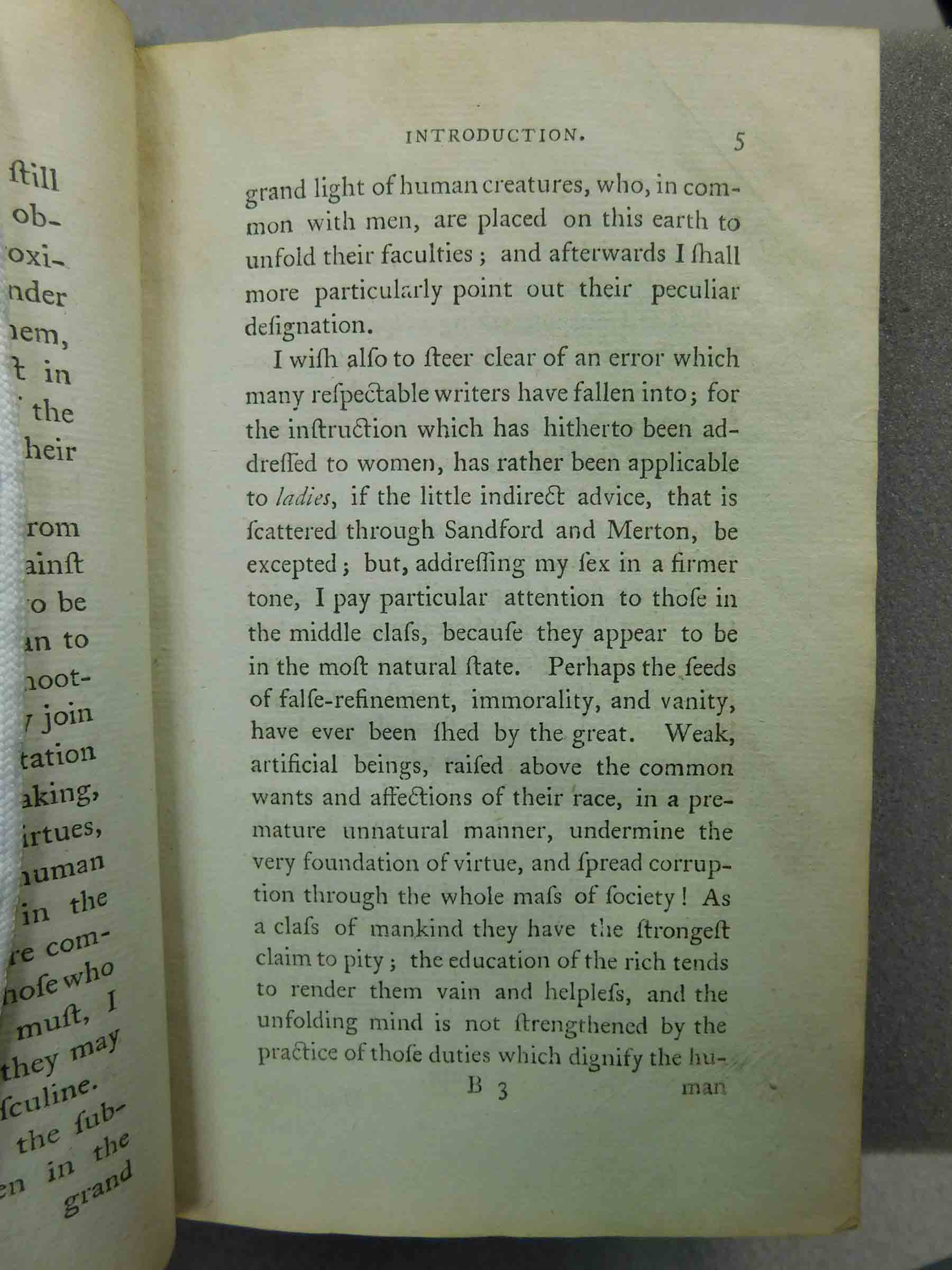

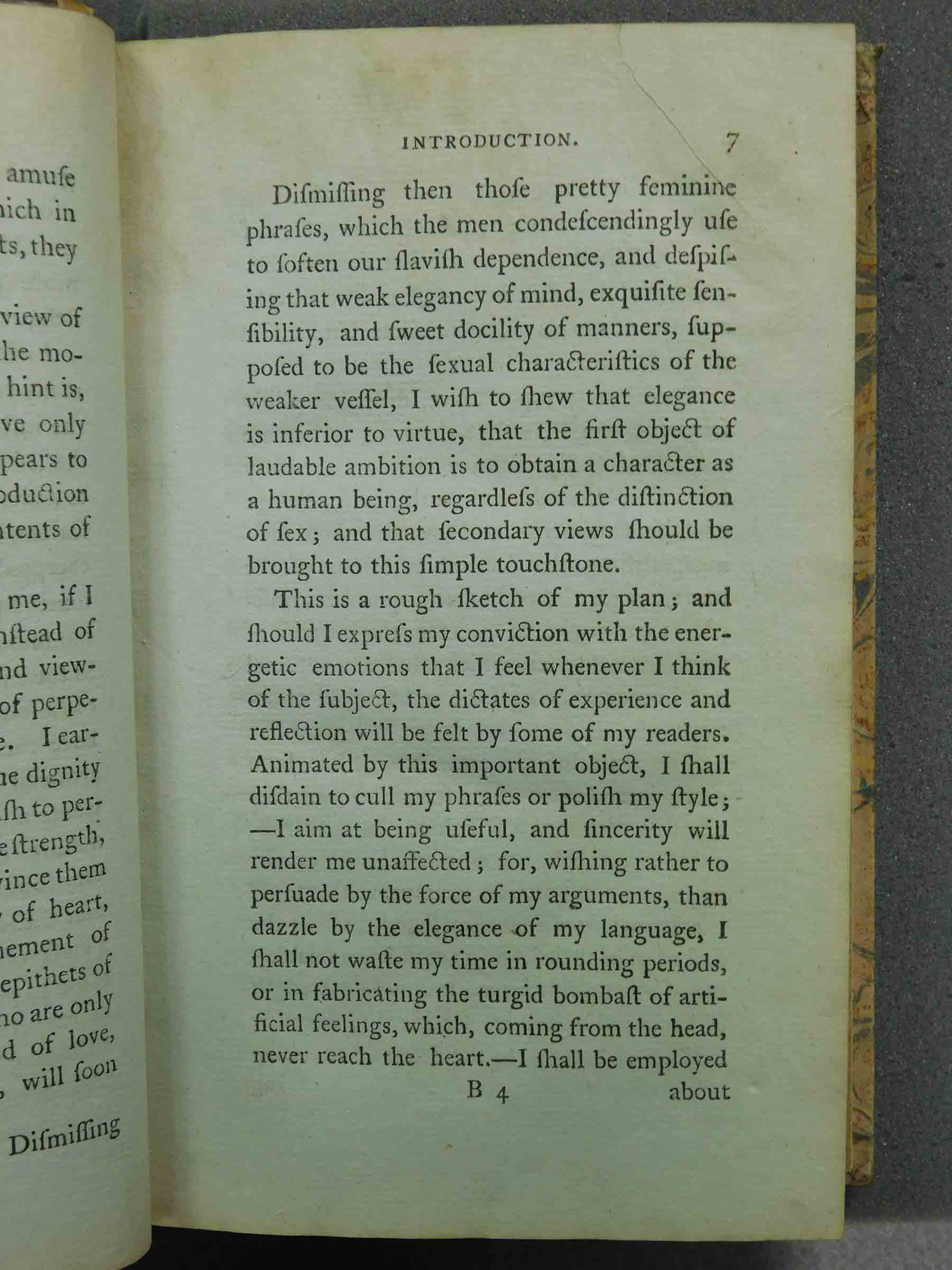

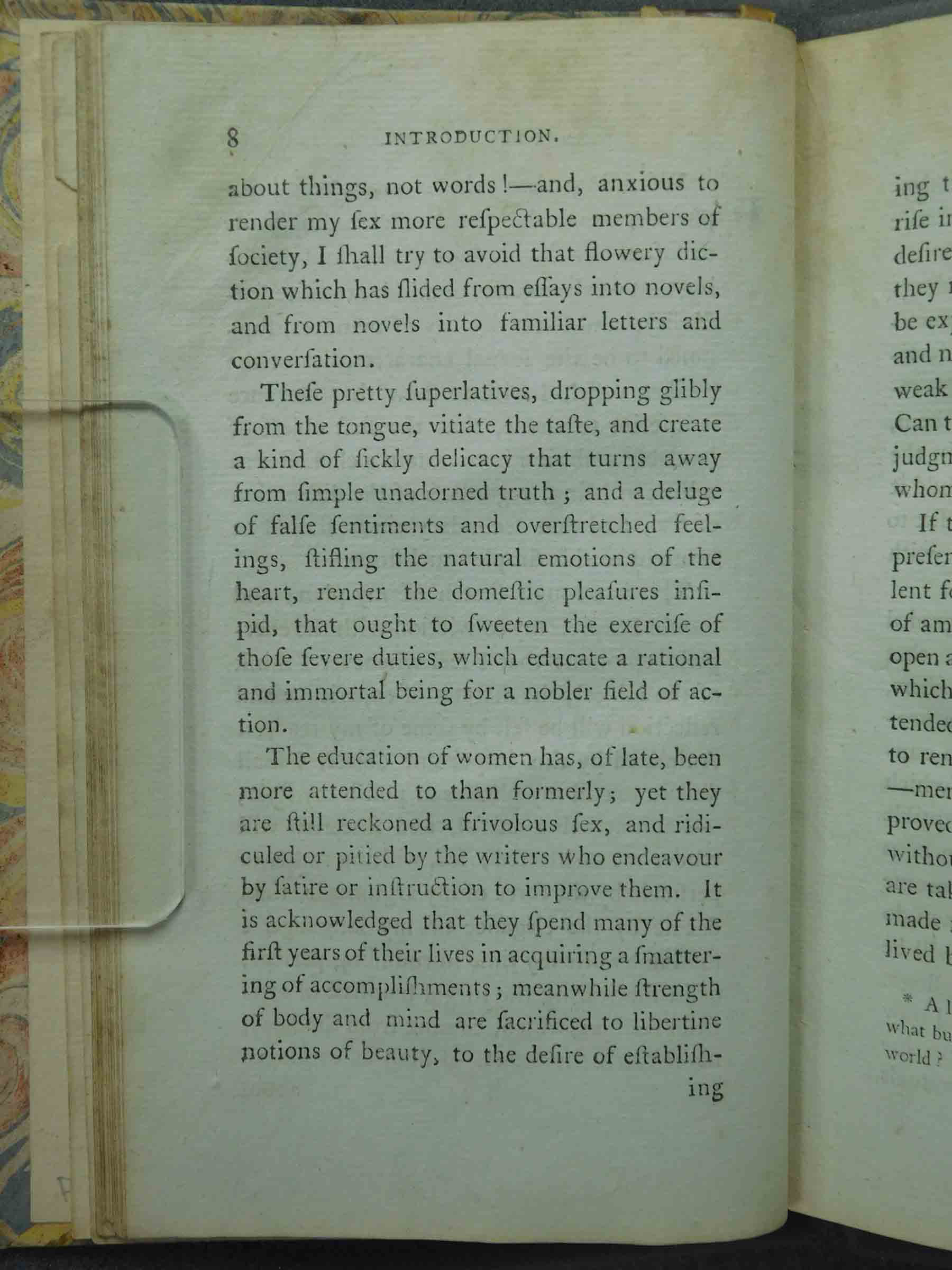

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London. - [MUstudstaff]mahometanism

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London. - [MUstudstaff]mahometanism

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons. - [BT]education

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons. - [BT]education

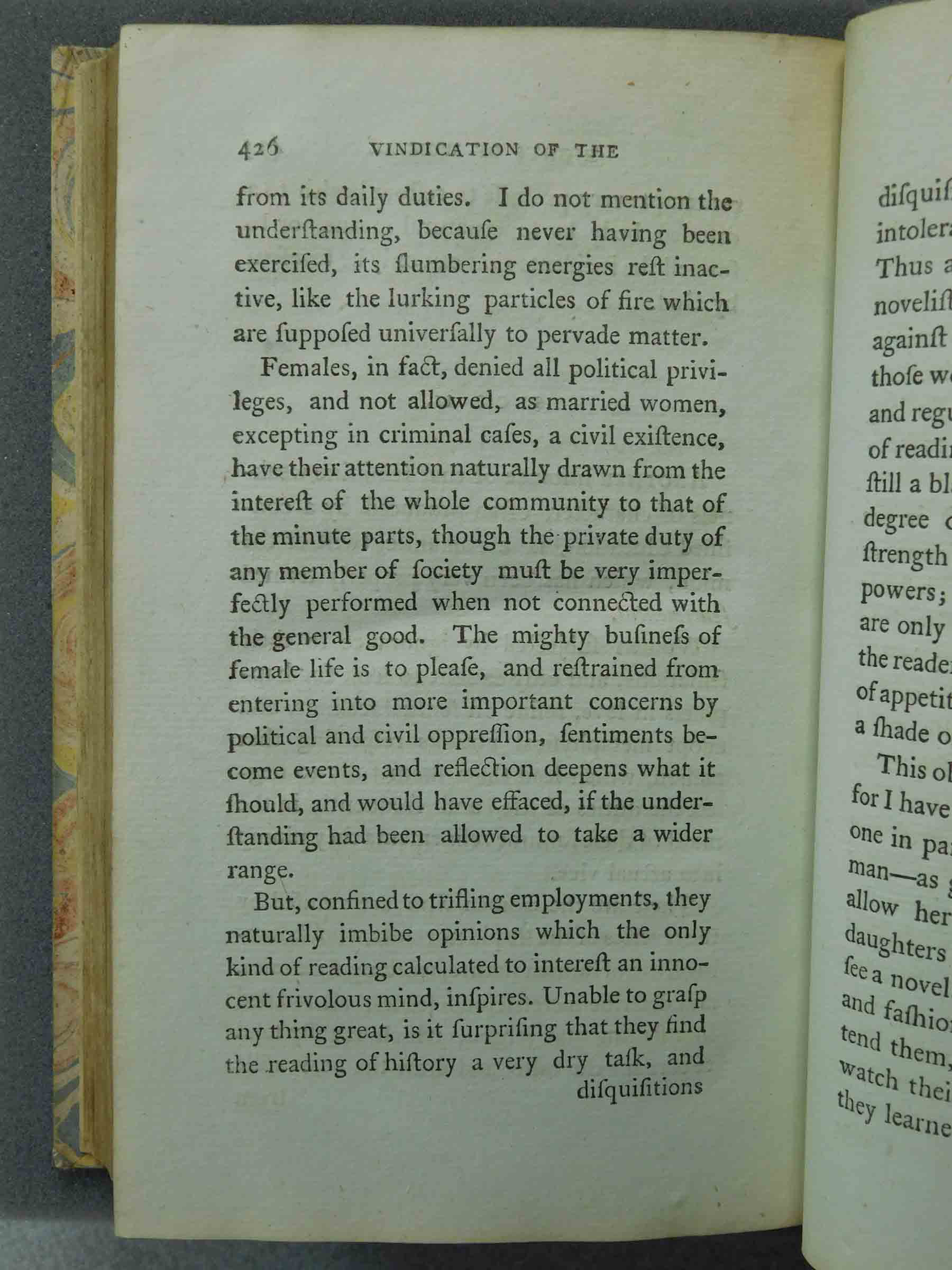

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library. - [NB]trifling_employments

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library. - [NB]trifling_employments

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work. - [MM]history This is likely a reference to

discussions about the hierarchy of genres during the eighteenth century. Dorothee Birke,

author of Writing the Reader: Configurations of Cultural Practice in English Novel

(2016), explains that historical and philosophical works were seen to have

higher value than novels and poetry. The reason behind such a hierarchical placement is

the perception of fictional reading to be connected with ignorance as people are fed

unrealistic words. Thus, historical and philosophical works which were often based on

truth and it reality, were insightful readings that were ranked higher than unrealistic

or exaggerated works (Birke 63). - [DN]sandford_merton Likely a reference to a popular

children’s book written in the eighteenth century, Sandford and

Merton (1783), by Thomas Day, is about two boys who grow up differently based on

social status. According to

Stephen Bending and Stephen Bygrave, the book is an indictment of upper class

"effete" masculinity (23). Tommy Merton is spoiled by middle class privileges and needs

to be re-educated to become as fine a man as Sandford, whose lower-class status

challenged him to develop, physically and mentally, into an admirable young man (3-4).

Interested viewers can also read an abridged

version of Day’s children’s book, published in 1792, at the Internet Archive. - [SV]novelistsWollstonecraft's question refers to an

ongoing discussion about the work of novel-reading on young girls' intellectual growth.

It was thought dangerous for women to read novels because society feared that they would

not, as Anna North writes in "When Novels Were Bad for You," be able to "differentiate between fiction and

life." - [KS]bubbled

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work. - [MM]history This is likely a reference to

discussions about the hierarchy of genres during the eighteenth century. Dorothee Birke,

author of Writing the Reader: Configurations of Cultural Practice in English Novel

(2016), explains that historical and philosophical works were seen to have

higher value than novels and poetry. The reason behind such a hierarchical placement is

the perception of fictional reading to be connected with ignorance as people are fed

unrealistic words. Thus, historical and philosophical works which were often based on

truth and it reality, were insightful readings that were ranked higher than unrealistic

or exaggerated works (Birke 63). - [DN]sandford_merton Likely a reference to a popular

children’s book written in the eighteenth century, Sandford and

Merton (1783), by Thomas Day, is about two boys who grow up differently based on

social status. According to

Stephen Bending and Stephen Bygrave, the book is an indictment of upper class

"effete" masculinity (23). Tommy Merton is spoiled by middle class privileges and needs

to be re-educated to become as fine a man as Sandford, whose lower-class status

challenged him to develop, physically and mentally, into an admirable young man (3-4).

Interested viewers can also read an abridged

version of Day’s children’s book, published in 1792, at the Internet Archive. - [SV]novelistsWollstonecraft's question refers to an

ongoing discussion about the work of novel-reading on young girls' intellectual growth.

It was thought dangerous for women to read novels because society feared that they would

not, as Anna North writes in "When Novels Were Bad for You," be able to "differentiate between fiction and

life." - [KS]bubbled

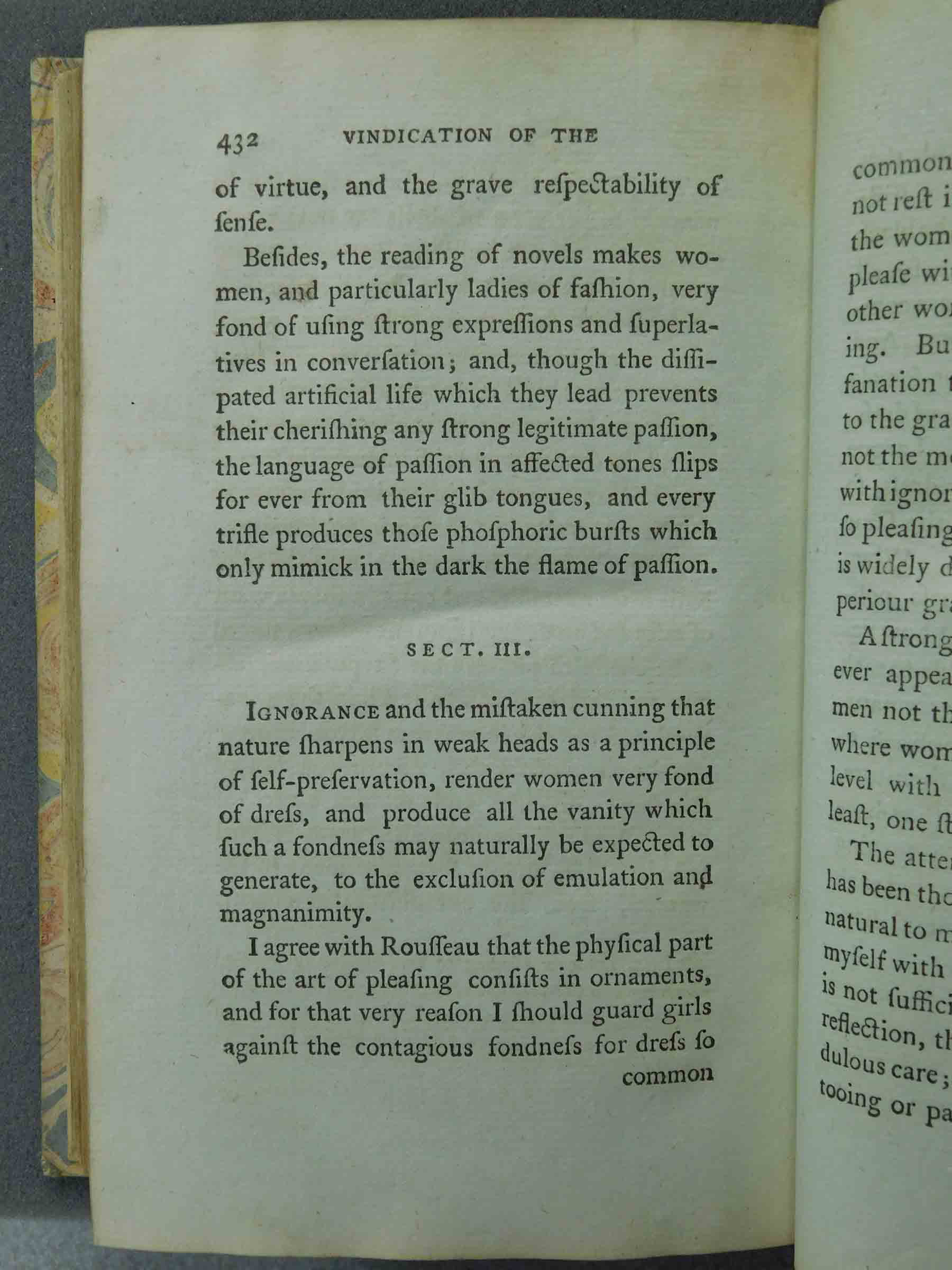

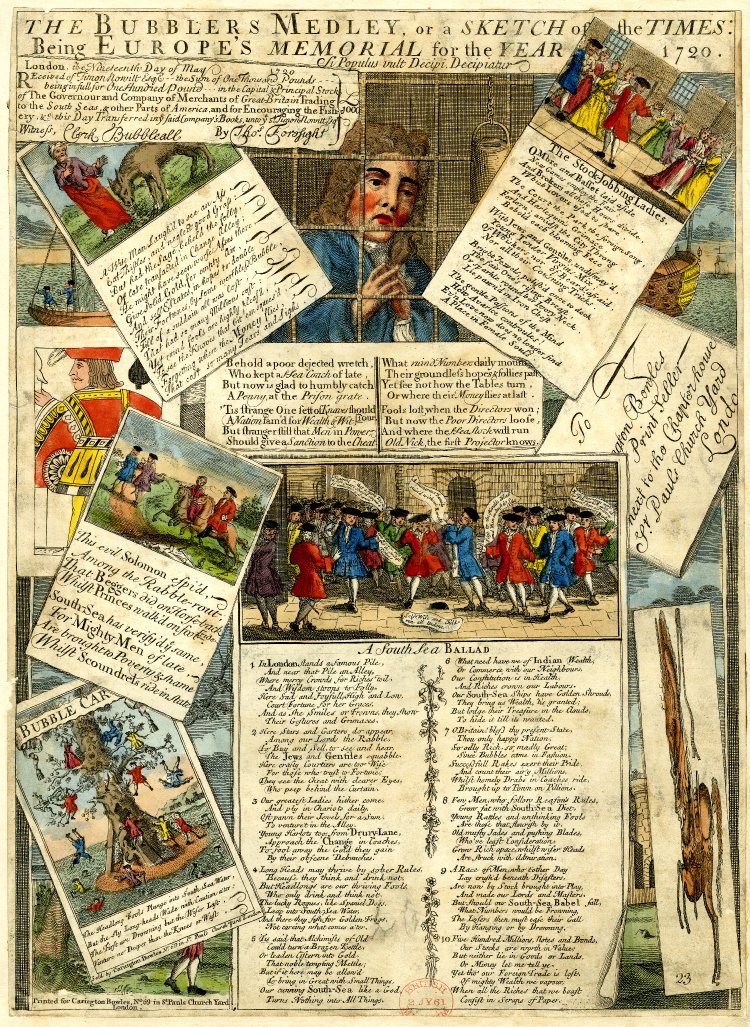

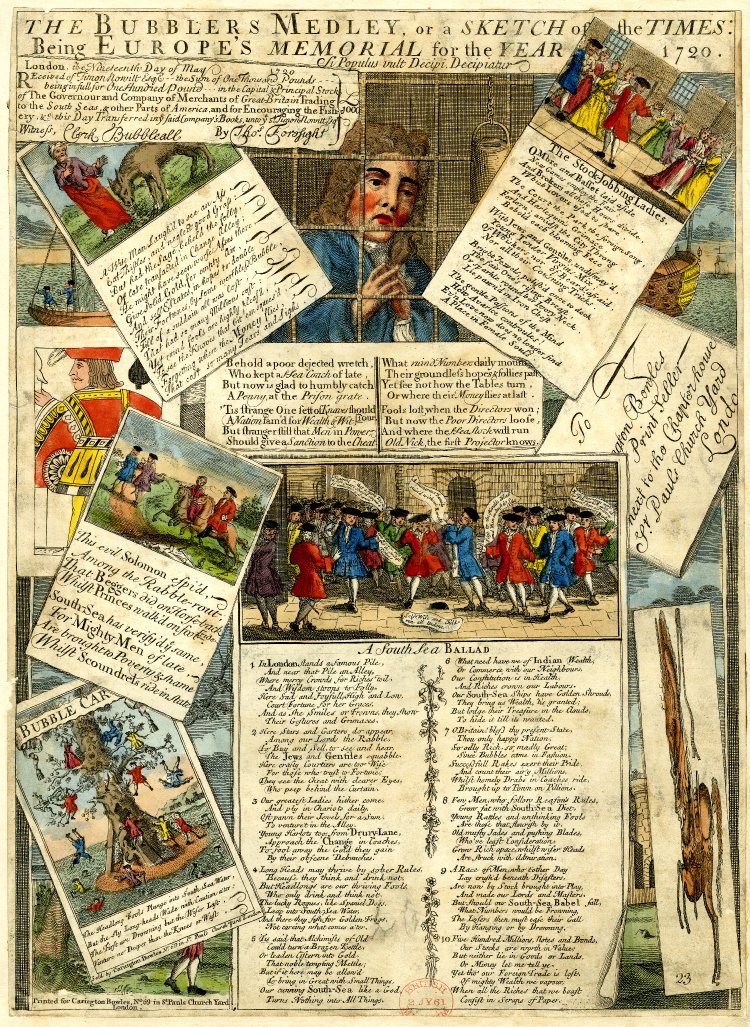

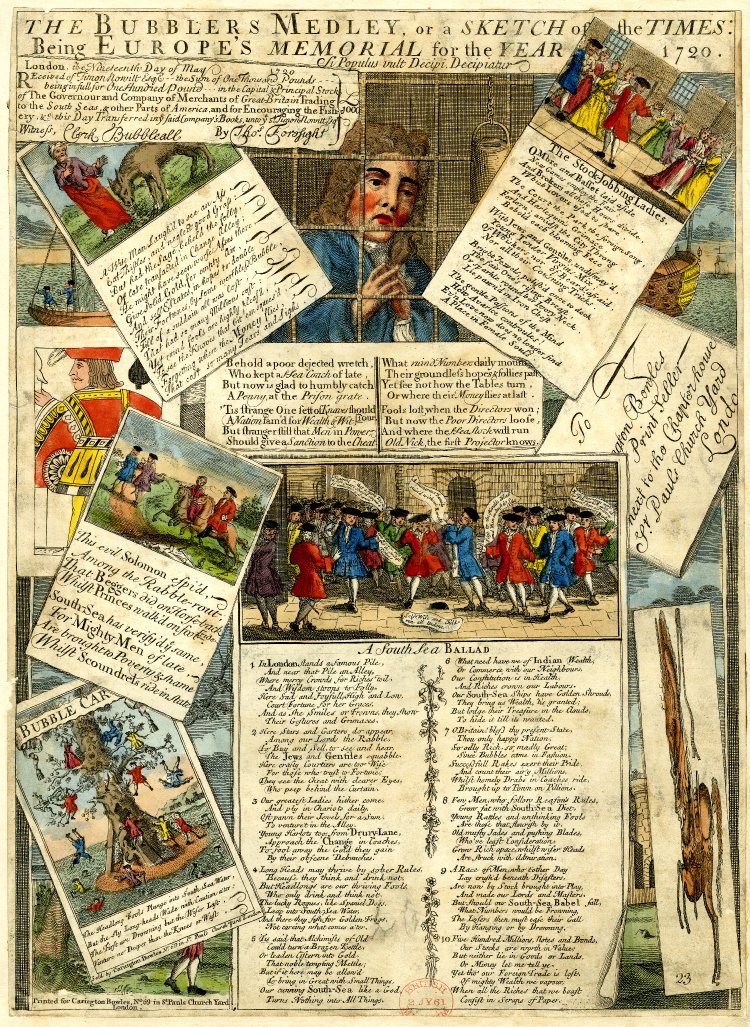

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of

conduct books and their false depiction of women. "Bubbled" in this usage is also

derived from the devastating financial bubble in the eighteenth century, including the

South Sea Bubble of 1720. Many engravings and satirical prints of the time depict how

the people were deceived and cheated financially, most notably, The

Bubbler’s Medley, or a Sketch of the Times being Europe’s Memoriam for 1720.

The image included here is from the British Museum's online collection. To read more, visit Harvard Business School’s

online exhibit on the South Sea Bubble, and the source of this annotation. - [JMF]conduct

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of

conduct books and their false depiction of women. "Bubbled" in this usage is also

derived from the devastating financial bubble in the eighteenth century, including the

South Sea Bubble of 1720. Many engravings and satirical prints of the time depict how

the people were deceived and cheated financially, most notably, The

Bubbler’s Medley, or a Sketch of the Times being Europe’s Memoriam for 1720.

The image included here is from the British Museum's online collection. To read more, visit Harvard Business School’s

online exhibit on the South Sea Bubble, and the source of this annotation. - [JMF]conduct

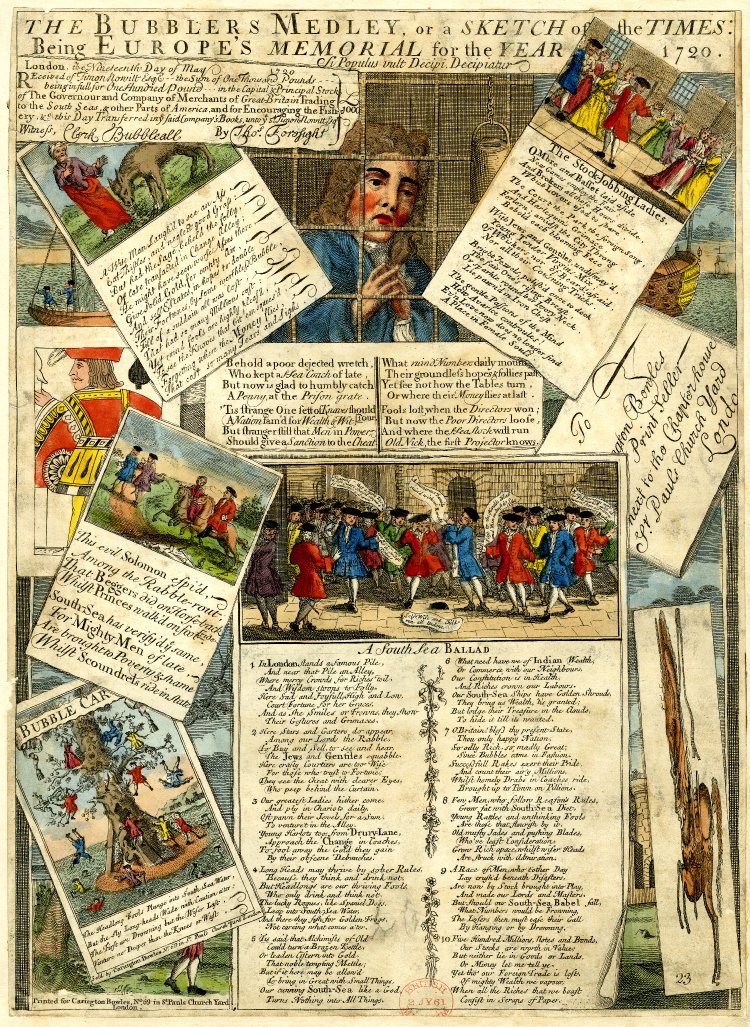

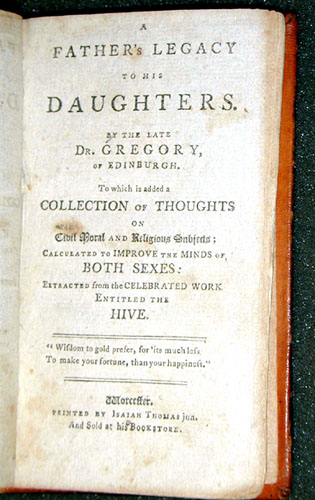

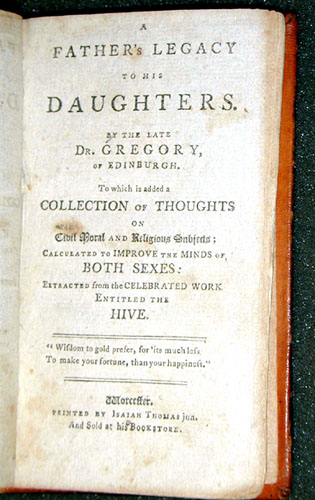

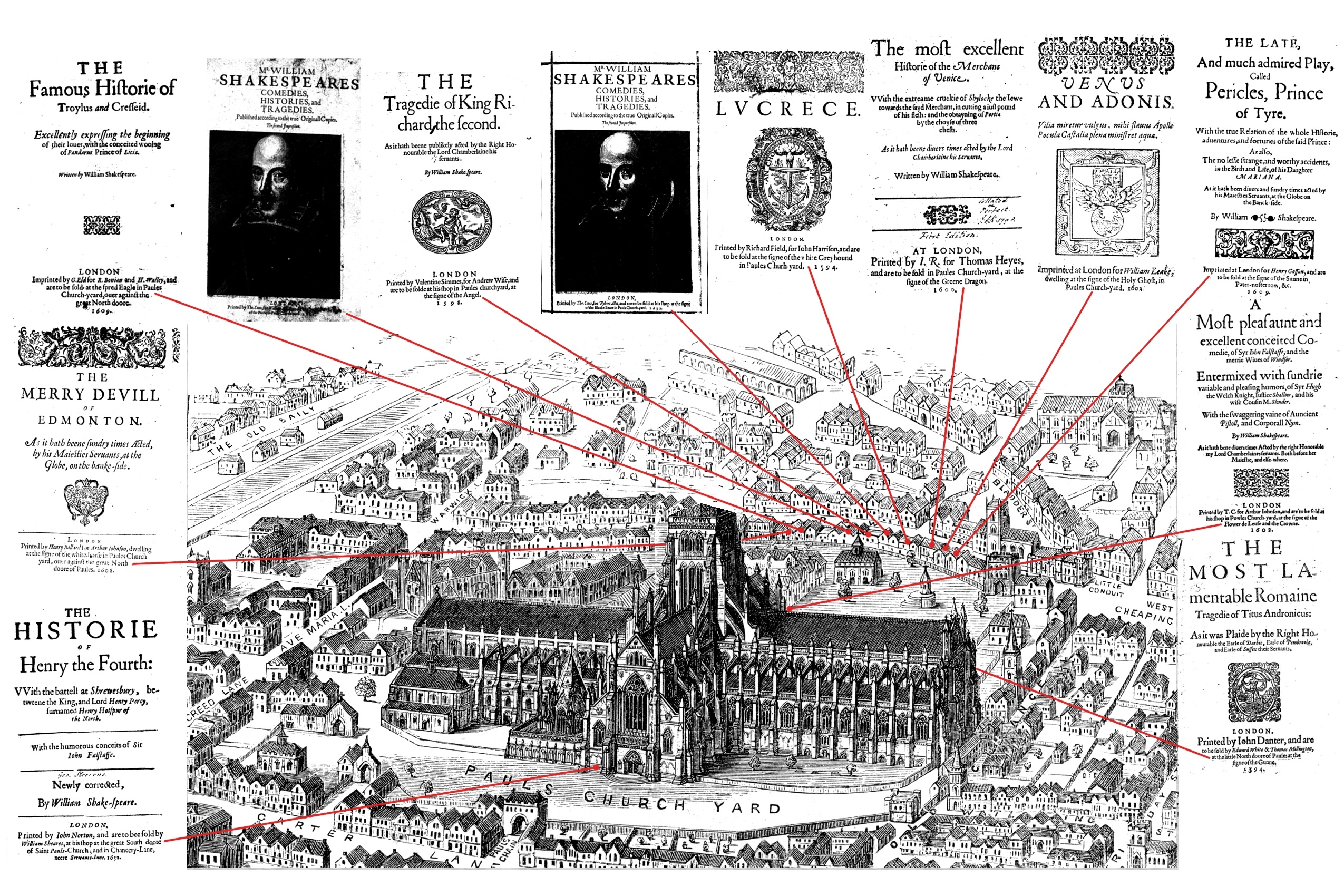

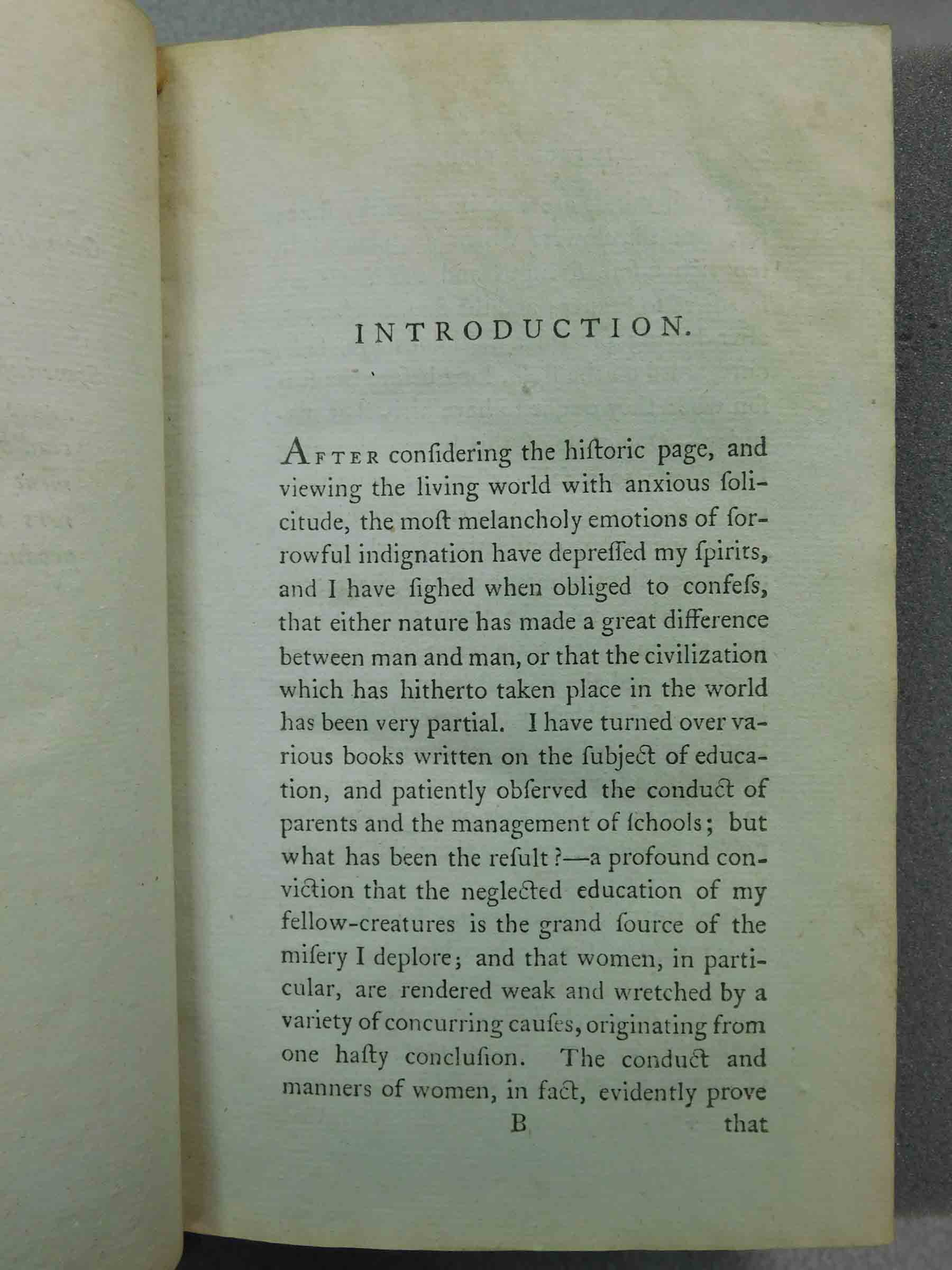

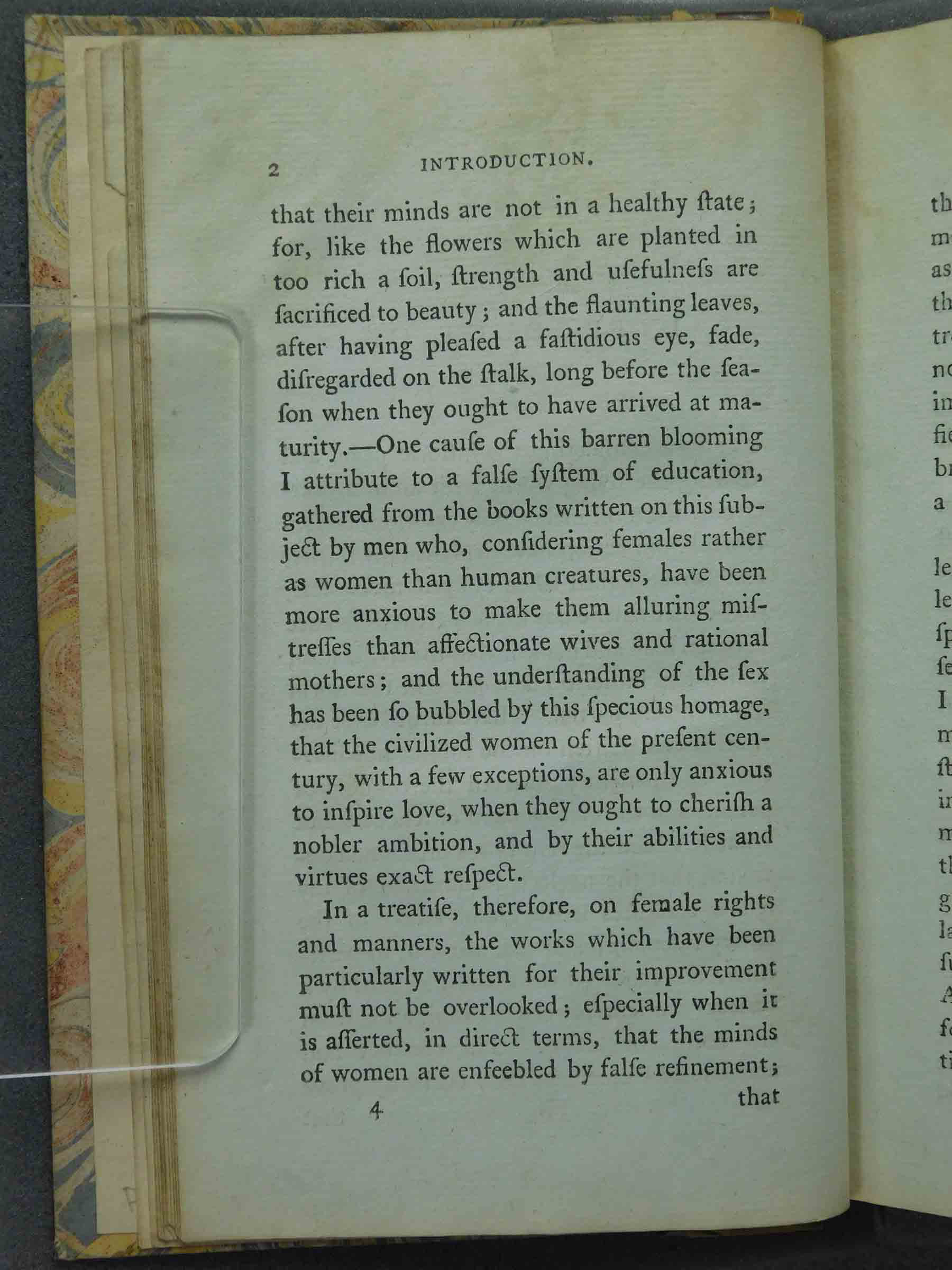

Source: The Title page of Gregory's conduct book

This is most likely a reference to Dr. John Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, a conduct book written prior

to Dr. Gregory’s wife’s passing in 1761 and addressed to his daughters about etiquette,

religion, conduct, and behaviors. Wollstonecraft references this book directly in many

of her arguments. The image of the book's title page (1795) is from the University of Delaware Special Collections Department is from the National Library of Scotland. View a 1793 edition of A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters at the Internet

Archive. - [BT]johnson

Source: The Title page of Gregory's conduct book

This is most likely a reference to Dr. John Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, a conduct book written prior

to Dr. Gregory’s wife’s passing in 1761 and addressed to his daughters about etiquette,

religion, conduct, and behaviors. Wollstonecraft references this book directly in many

of her arguments. The image of the book's title page (1795) is from the University of Delaware Special Collections Department is from the National Library of Scotland. View a 1793 edition of A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters at the Internet

Archive. - [BT]johnson

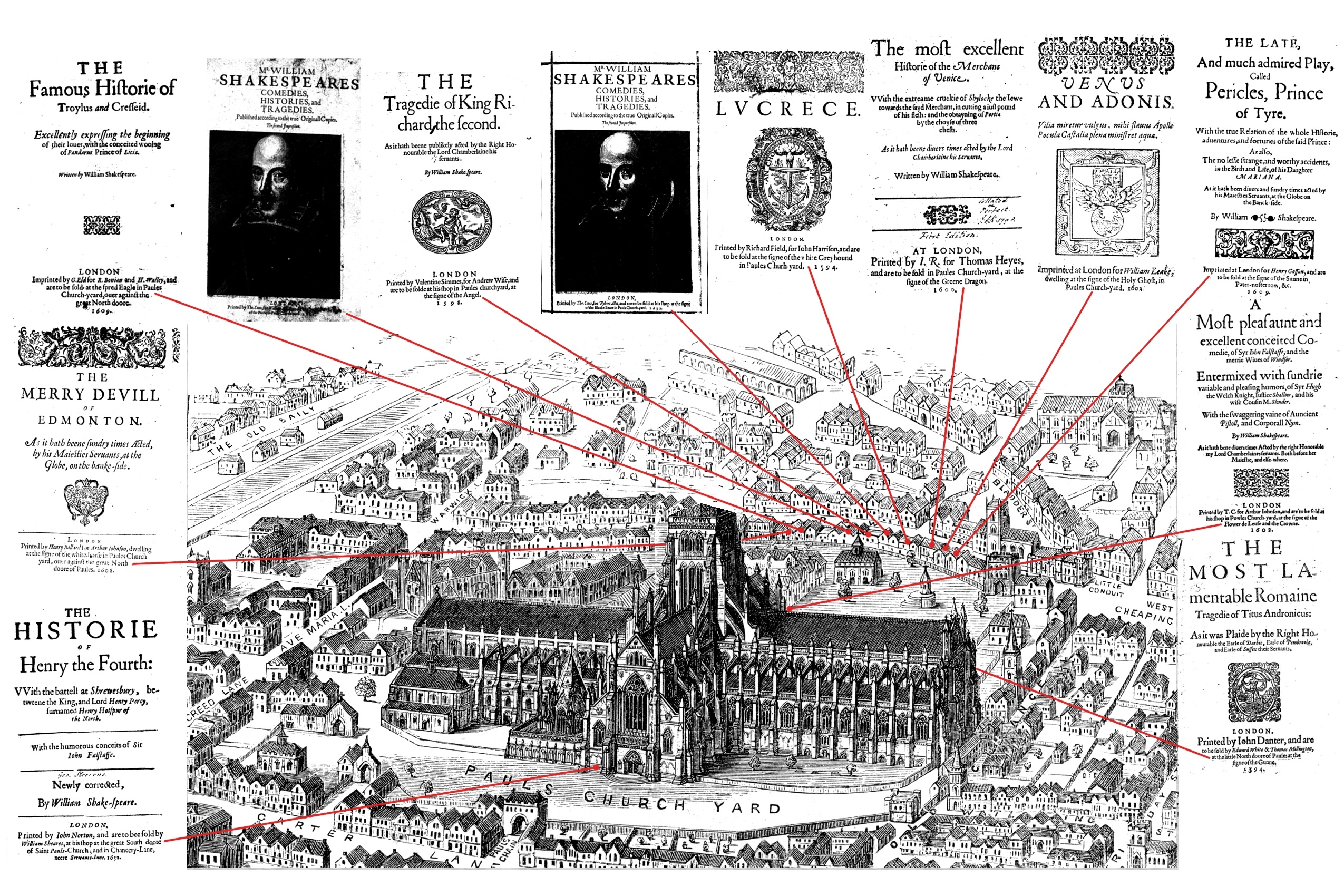

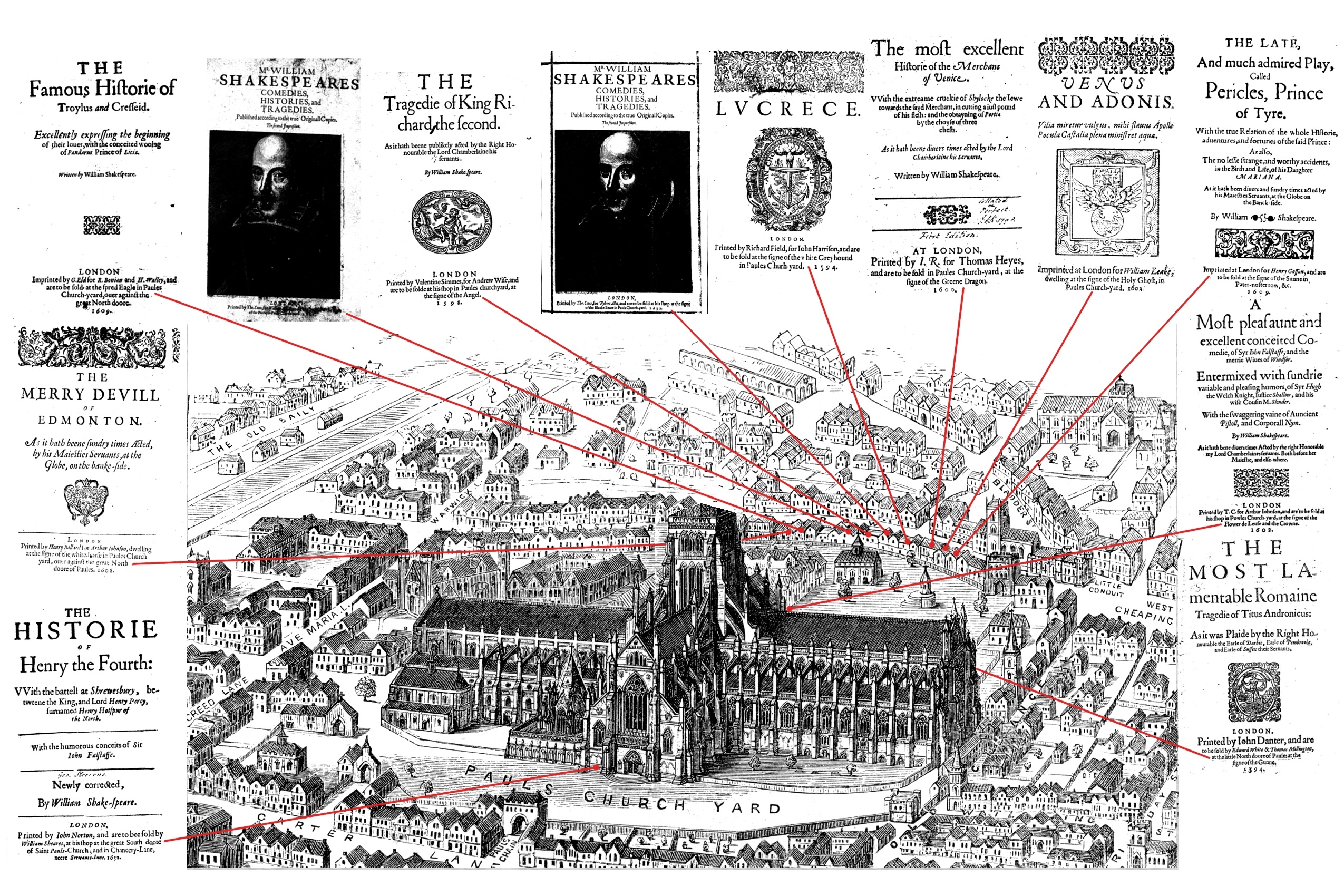

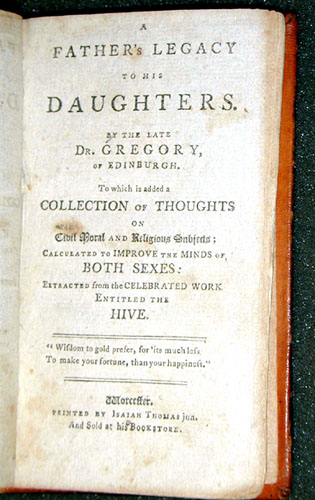

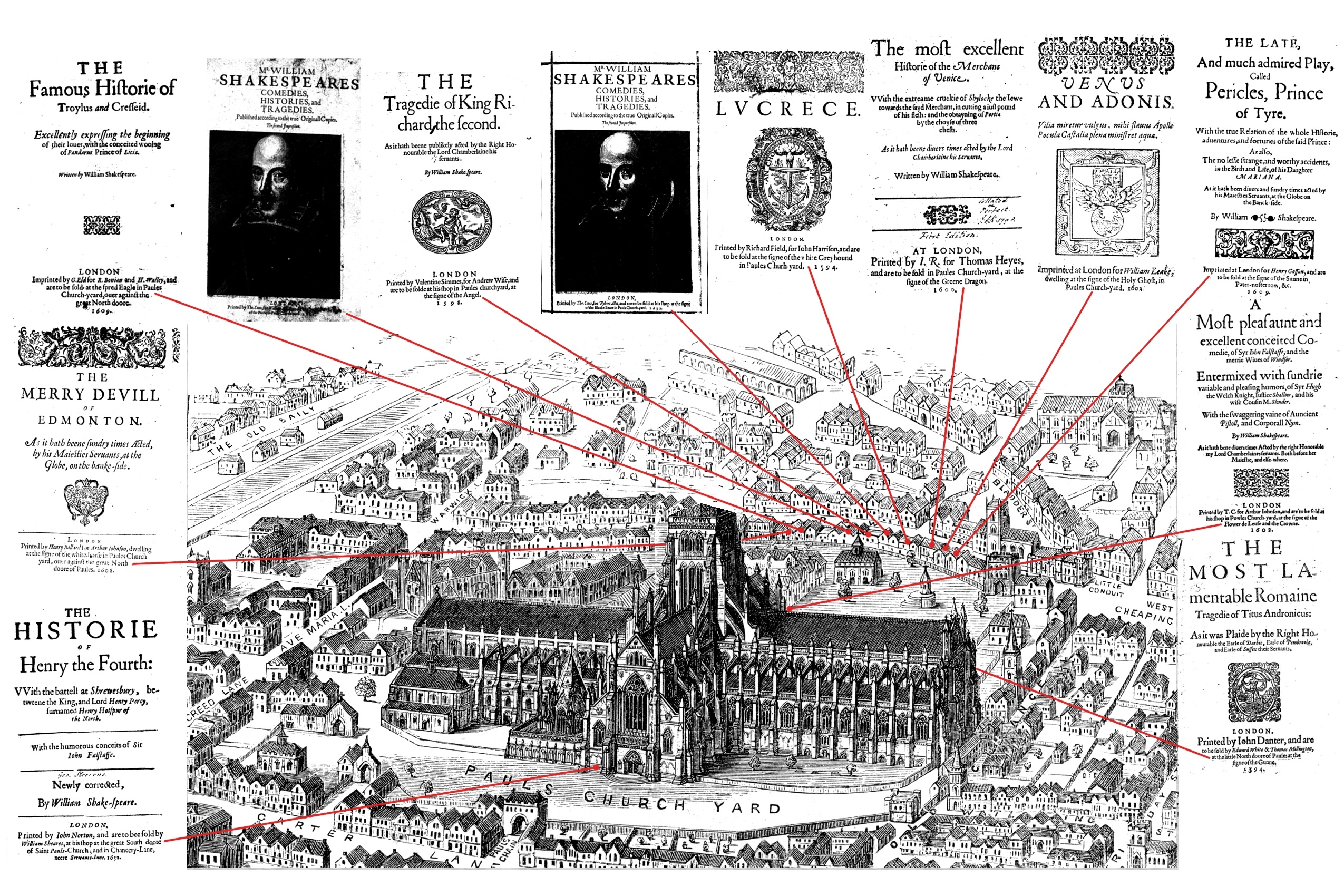

Throughout the eighteenth century, St. Paul’s Church Yard was the center of the

publishing trade. Wollstonecraft's Vindications was published by

Joseph Johnson, a liberal publisher with radical views, who published work by William

Godwin, Joseph Priestly, and William Blake. Wollstonecraft lived near St. Paul’s Church

Yard and spent many hours in this workshop as Joseph Johnson gave her writing and

translating jobs throughout the day. For more on the relationship between Mary

Wollstonecraft and Joseph Johnson, see this letter from Wollstonecraft to her publisher reprinted in The

American Reader. The image here, from a University of Louisville news

article on William Shakespeare's first folio, shows the locations of printers around St.

Paul's during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. - [TH]elegance

Throughout the eighteenth century, St. Paul’s Church Yard was the center of the

publishing trade. Wollstonecraft's Vindications was published by

Joseph Johnson, a liberal publisher with radical views, who published work by William

Godwin, Joseph Priestly, and William Blake. Wollstonecraft lived near St. Paul’s Church

Yard and spent many hours in this workshop as Joseph Johnson gave her writing and

translating jobs throughout the day. For more on the relationship between Mary

Wollstonecraft and Joseph Johnson, see this letter from Wollstonecraft to her publisher reprinted in The

American Reader. The image here, from a University of Louisville news

article on William Shakespeare's first folio, shows the locations of printers around St.

Paul's during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. - [TH]elegance

Elegance in the 18th century has a specific meaning when applied to

women. According to Robert

W. Jones, author of Gender and the Formation of Taste in

Eighteenth-Century Britain, feminine elegance is the combination of

docility and enticement of men. In the eighteenth century, elegance is feminized with

the goal that women should use it to please and seduce men through beauty and

refinement. Elegance of the eighteenth century is the area of the pleasing and amiable

actions from women to men, these beauty standards were important and a source of

intrigue for the culture (Jones 109). The image here, drawn from the National Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC, shows An Elegant Lady Playing a Cittern (1770), by Nathaniel

Dance-Holland. - [SM]virtue Mary Wollstonecraft uses "virtue" with

its eighteenth-century sense of power. Men were often seen as virtuous because of their

physical strength, whereas women acquired virtue through sensibility and virginity.

Wollstonecraft argues that true virtue can only exist with knowledge and education.

Therefore, women must be properly educated or they would only be mimicking true virtue.

Views of Women in

Eighteenth Century Literature," published in the International

Journal of Communication Research by Adrian Brunello and Florina-Elena

Borsan reviews the way that understandings of womanhood shifted in the period, resulting

in the need for an exterior display of virtue, rather than true virtue (325-326). clicking here will direct you to the UK National Gallery of Art, showing An Allegory of Virtue and Riches, painted in 1667 by Godfried

Schalcken.

- [RB]schools

Elegance in the 18th century has a specific meaning when applied to

women. According to Robert

W. Jones, author of Gender and the Formation of Taste in

Eighteenth-Century Britain, feminine elegance is the combination of

docility and enticement of men. In the eighteenth century, elegance is feminized with

the goal that women should use it to please and seduce men through beauty and

refinement. Elegance of the eighteenth century is the area of the pleasing and amiable

actions from women to men, these beauty standards were important and a source of

intrigue for the culture (Jones 109). The image here, drawn from the National Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC, shows An Elegant Lady Playing a Cittern (1770), by Nathaniel

Dance-Holland. - [SM]virtue Mary Wollstonecraft uses "virtue" with

its eighteenth-century sense of power. Men were often seen as virtuous because of their

physical strength, whereas women acquired virtue through sensibility and virginity.

Wollstonecraft argues that true virtue can only exist with knowledge and education.

Therefore, women must be properly educated or they would only be mimicking true virtue.

Views of Women in

Eighteenth Century Literature," published in the International

Journal of Communication Research by Adrian Brunello and Florina-Elena

Borsan reviews the way that understandings of womanhood shifted in the period, resulting

in the need for an exterior display of virtue, rather than true virtue (325-326). clicking here will direct you to the UK National Gallery of Art, showing An Allegory of Virtue and Riches, painted in 1667 by Godfried

Schalcken.

- [RB]schools

The

most common schools available for lower working class families in eighteenth-century

were dame schools. An elderly, barely literate, woman would teach reading and sewing for

a small fee. Read more in English Heritage’s brochure on England’s School. The

image of children learning in a dame school, painted by Thomas Webster (1845), is housed

in the Tate Art Museum, London.

- [FB]sentimental The sentimental novel is a genre which

rose into popularity in the eighteenth century. This genre is characterized by

excessively passionate characters, tearful scenes and dramatic, flowery dialogue. Mary

Wollstonecraft may be using the popularity of these novels among young women to explain

their apparent lack of rationality rather than claiming irrationality to be a naturally

female trait. Read more about the sentimental novel in

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- [ES]novelsAs novels became more accessible they

became more popular. Some believed that excessive exposure to fiction novels would cause

readers to lose touch with reality and identify with characters to the point of

mimicking dangerous or immoral behavior. Read more about a popular novel that was blamed

for youthful suicides in this article by Frank Furedi from

History Today. - [ES]ranks The different ranks of society in

England during the eighteenth century were not simply divided between the rich or poor.

According to the eighteenth-century writer Daniel Defoe, there were seven categories:

the great, the rich, the middle sort, the working trades, the country people, the poor,

and the miserable. The country still relied on agriculture and, although some still died

of hunger, there was usually enough food to go around. Trade was increasing and more men

and women acquired jobs in industry. However, wealth was unequally distributed, with

only 5% of the national income belonging to the general population. Read more in this

Encyclopedia Britannica entry for eighteenth-century

Britain, and the source of this annotation. - [MR]seraglio

The

most common schools available for lower working class families in eighteenth-century

were dame schools. An elderly, barely literate, woman would teach reading and sewing for

a small fee. Read more in English Heritage’s brochure on England’s School. The

image of children learning in a dame school, painted by Thomas Webster (1845), is housed

in the Tate Art Museum, London.

- [FB]sentimental The sentimental novel is a genre which

rose into popularity in the eighteenth century. This genre is characterized by

excessively passionate characters, tearful scenes and dramatic, flowery dialogue. Mary

Wollstonecraft may be using the popularity of these novels among young women to explain

their apparent lack of rationality rather than claiming irrationality to be a naturally

female trait. Read more about the sentimental novel in

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- [ES]novelsAs novels became more accessible they

became more popular. Some believed that excessive exposure to fiction novels would cause

readers to lose touch with reality and identify with characters to the point of

mimicking dangerous or immoral behavior. Read more about a popular novel that was blamed

for youthful suicides in this article by Frank Furedi from

History Today. - [ES]ranks The different ranks of society in

England during the eighteenth century were not simply divided between the rich or poor.

According to the eighteenth-century writer Daniel Defoe, there were seven categories:

the great, the rich, the middle sort, the working trades, the country people, the poor,

and the miserable. The country still relied on agriculture and, although some still died

of hunger, there was usually enough food to go around. Trade was increasing and more men

and women acquired jobs in industry. However, wealth was unequally distributed, with

only 5% of the national income belonging to the general population. Read more in this

Encyclopedia Britannica entry for eighteenth-century

Britain, and the source of this annotation. - [MR]seraglio

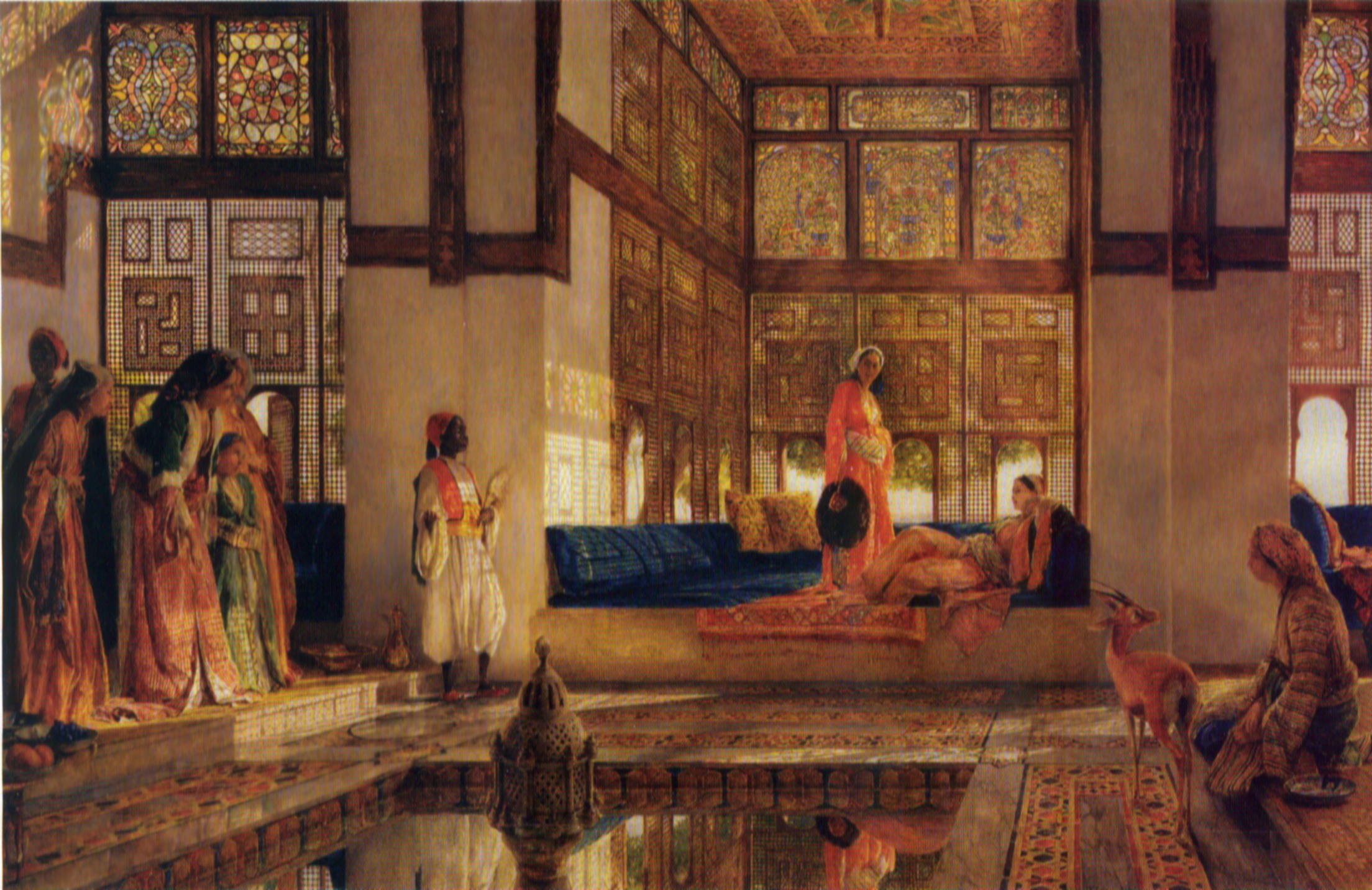

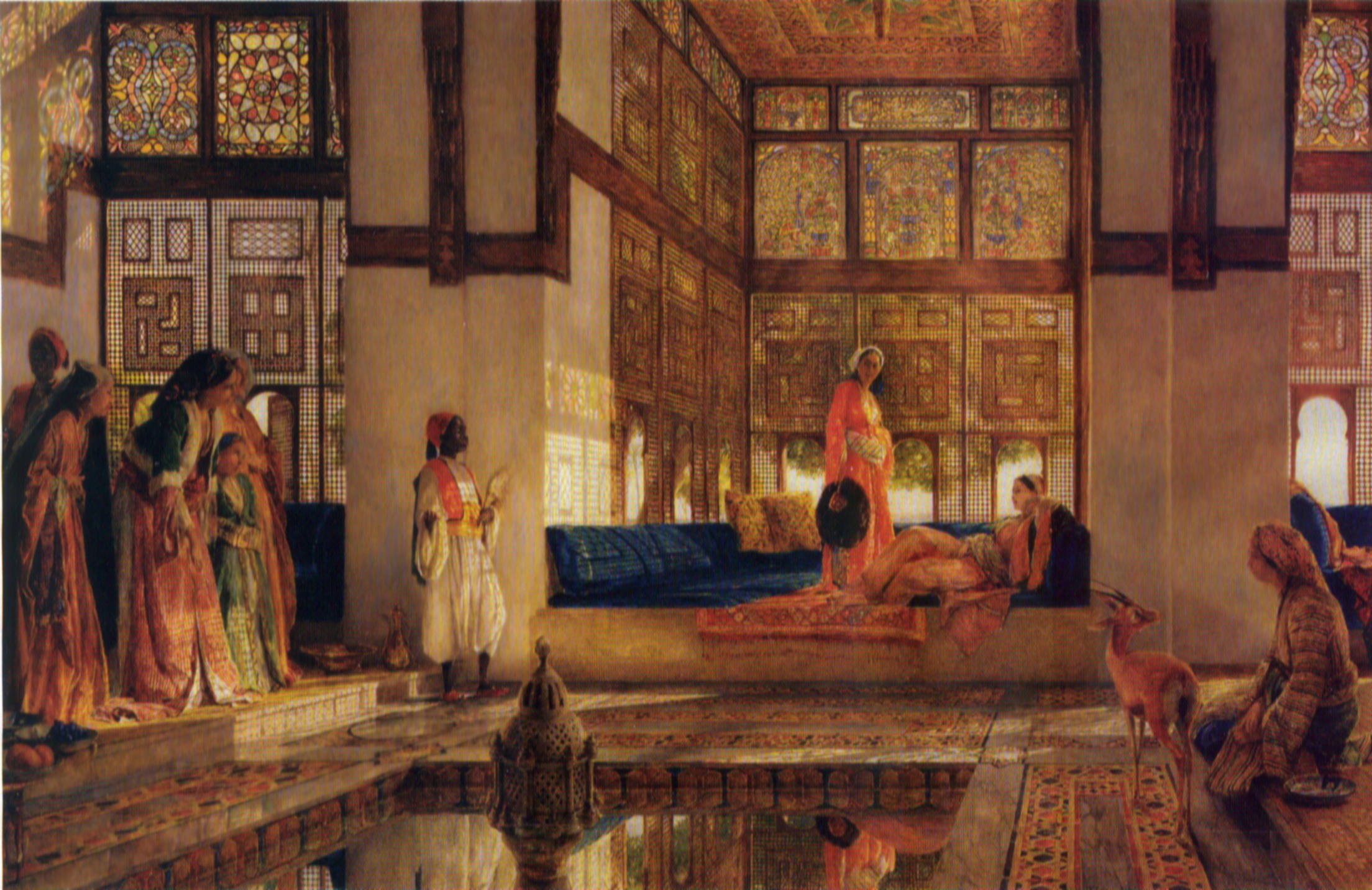

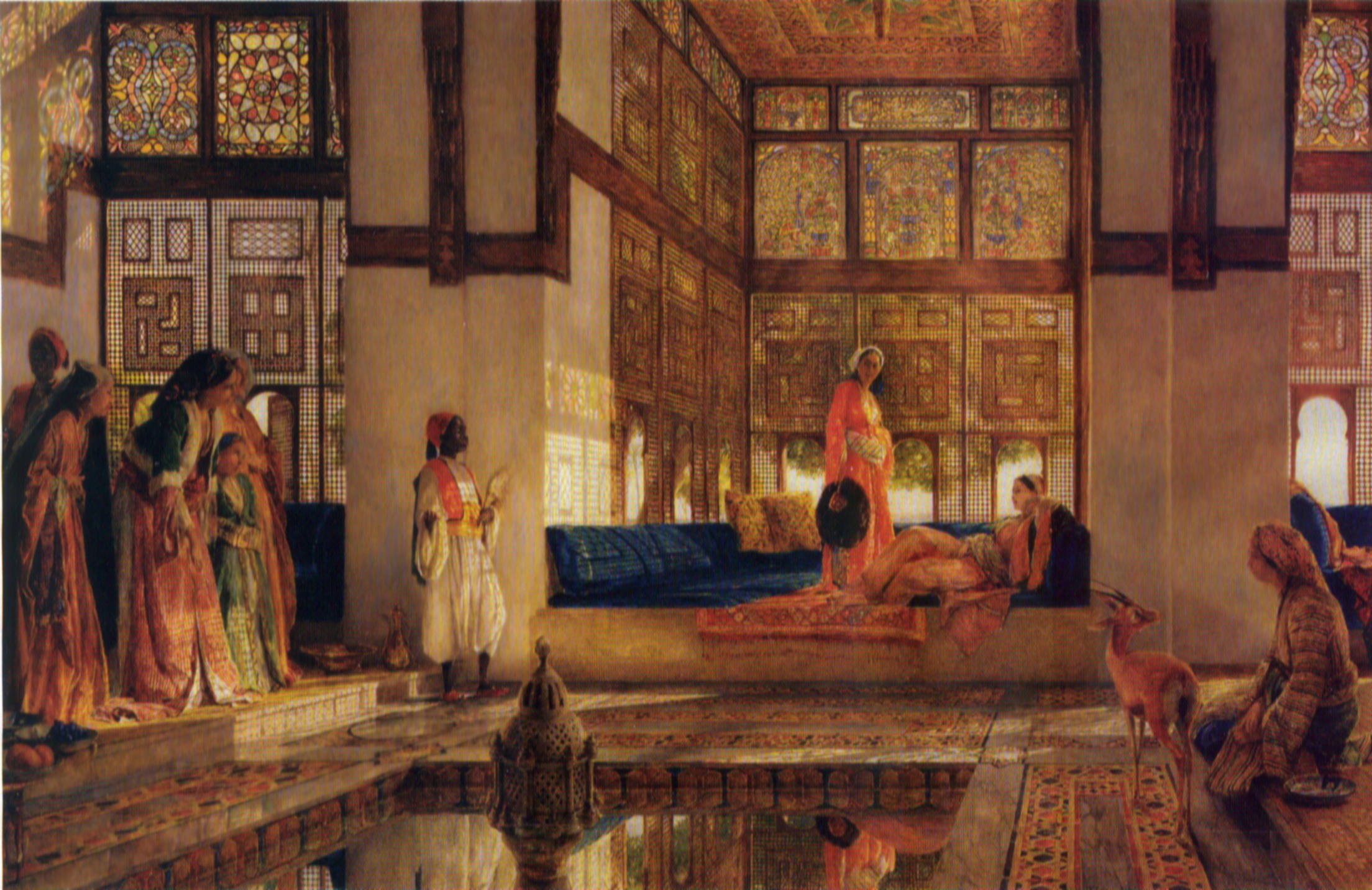

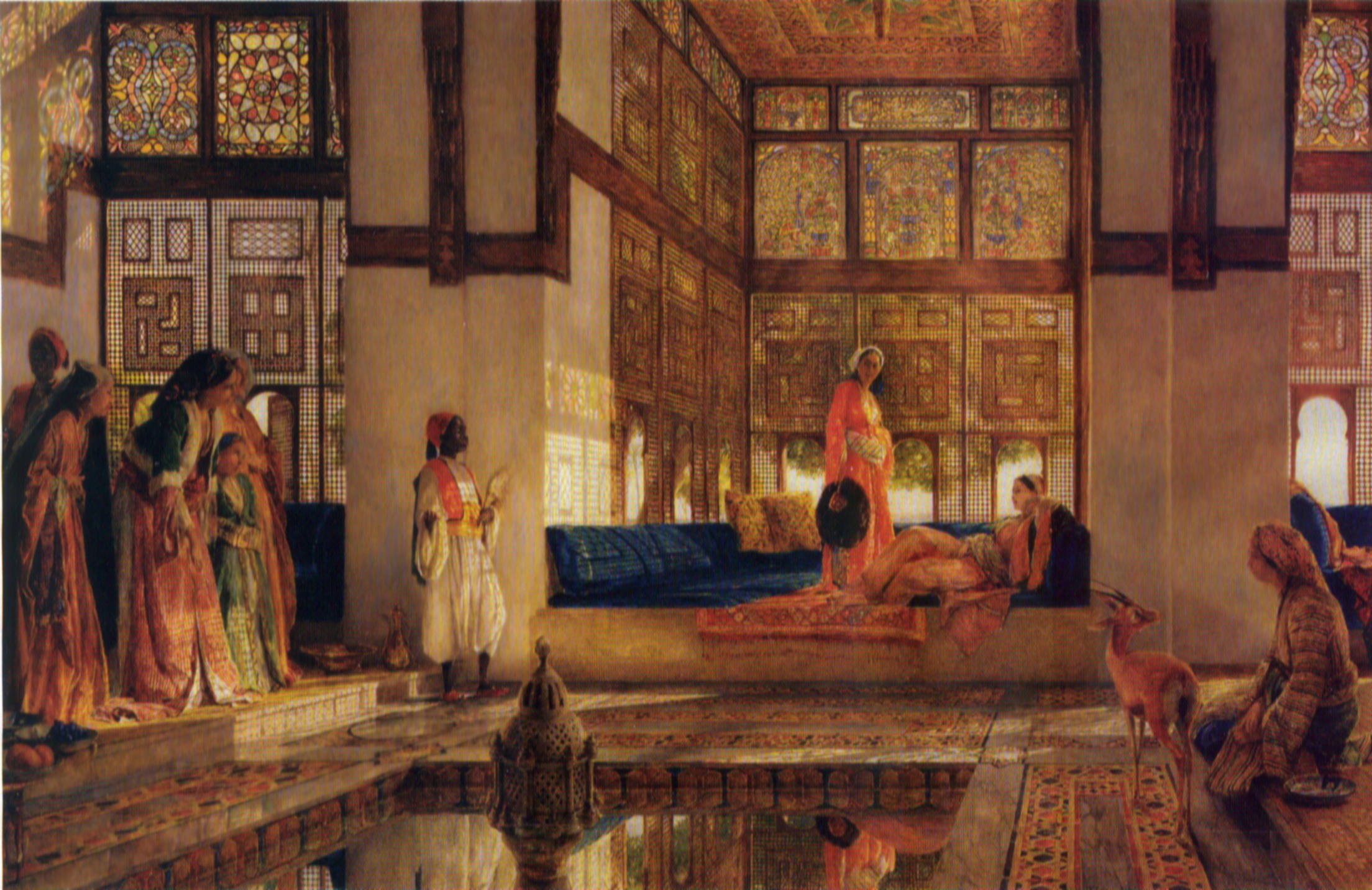

Wollstonecraft’s argument in A Vindication of the

Rights of Woman is that women spend most of their lives acquiring knowledge to

be perfect wives instead of strengthening their minds and bodies to place a man. Because

the only way women can rise the world is through marriage, they are being groomed to

become lovers much like women in a Turkish seraglio, as Susan Gubar notes in "Feminist

Misogyny" (Gubar

151). Wollstonecraft is pointing out the lack of freedom for women. The image

included here illustrates the women’s quarter of a seraglio painted in 1873 by John

Frederick Lewis. This image is from Wikimedia Commons.

- [RDJ]dress

Wollstonecraft’s argument in A Vindication of the

Rights of Woman is that women spend most of their lives acquiring knowledge to

be perfect wives instead of strengthening their minds and bodies to place a man. Because

the only way women can rise the world is through marriage, they are being groomed to

become lovers much like women in a Turkish seraglio, as Susan Gubar notes in "Feminist

Misogyny" (Gubar

151). Wollstonecraft is pointing out the lack of freedom for women. The image

included here illustrates the women’s quarter of a seraglio painted in 1873 by John

Frederick Lewis. This image is from Wikimedia Commons.

- [RDJ]dress

In the eighteenth century, women were encouraged to focus on their

dress, meaning their overall attire, because as Dr. Gregory argues in A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, it was supposedly natural

to them (55). Women were dressed in hope of catching the attention of a man;

they would parade, or flaunt themselves to men, hoping to find a husband, which is the

only way for a woman to "rise in the world," as Wollstonecraft notes above (9).

Wollstonecraft didn’t want women to dress and flaunt themselves only for men’s

attention; she wanted women to focus on their own education. This portrait of Madame

Pompadour, located in the Alte Pinkothek Museum in Munich and via Wikimedia Commons, provides an example of

women’s attire in the 1700s in which Wollstonecraft was advising them not to do. Learn

more about eighteenth-century fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum. - [DF]governess According to Katheryn Hughes, the governess was one of the most familiar figures in the

Romantic period and throughout the Victorian period. Governesses were women who earned

their living by teaching and caring for other women’s children. Most governesses lived

with their employers and were paid a small salary on top of their board and lodging. The

governess was seen as an outsider, not quite fitting in with the family she governed for

but not exactly fitting in as a servant either. - [AH]manly

In the eighteenth century, women were encouraged to focus on their

dress, meaning their overall attire, because as Dr. Gregory argues in A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, it was supposedly natural

to them (55). Women were dressed in hope of catching the attention of a man;

they would parade, or flaunt themselves to men, hoping to find a husband, which is the

only way for a woman to "rise in the world," as Wollstonecraft notes above (9).

Wollstonecraft didn’t want women to dress and flaunt themselves only for men’s

attention; she wanted women to focus on their own education. This portrait of Madame

Pompadour, located in the Alte Pinkothek Museum in Munich and via Wikimedia Commons, provides an example of

women’s attire in the 1700s in which Wollstonecraft was advising them not to do. Learn

more about eighteenth-century fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum. - [DF]governess According to Katheryn Hughes, the governess was one of the most familiar figures in the

Romantic period and throughout the Victorian period. Governesses were women who earned

their living by teaching and caring for other women’s children. Most governesses lived

with their employers and were paid a small salary on top of their board and lodging. The

governess was seen as an outsider, not quite fitting in with the family she governed for

but not exactly fitting in as a servant either. - [AH]manly

"Manly virtues" in the eighteenth century refers to social

behavior that encourages men to be kind, loving, and courageous both in the home and in

the public domain. Since masculinity is, as Intertextual War: Edmund

Burke and the French Revolution in the Writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Paine,

and James Mackintosh by Steven Blakemore, states, a "restrictive misnomer for

qualities or virtues that are human," Mary Wollstonecraft opposes men that inveigh

against masculine women because of its imitation of manly virtues (Blakemore 42). The portrait here, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

by Thomas Gainsborough (1748), is housed in the National Gallery London. This painting,

via Wikimedia Commons, illustrates manliness in terms of gentility. - [RB]phosphorus

"Manly virtues" in the eighteenth century refers to social

behavior that encourages men to be kind, loving, and courageous both in the home and in

the public domain. Since masculinity is, as Intertextual War: Edmund

Burke and the French Revolution in the Writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Paine,

and James Mackintosh by Steven Blakemore, states, a "restrictive misnomer for

qualities or virtues that are human," Mary Wollstonecraft opposes men that inveigh

against masculine women because of its imitation of manly virtues (Blakemore 42). The portrait here, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

by Thomas Gainsborough (1748), is housed in the National Gallery London. This painting,

via Wikimedia Commons, illustrates manliness in terms of gentility. - [RB]phosphorus

Used by alchemists throughout the seventeenth century, phosphorous was

officially designated the thirteenth element by Antoine Lavosier in 1777. Quack

physicians incorporated the eerily-glowing phosphorous into their "cure all" medicines.

Here, Wollstonecraft may be referring to a long-standing association between the element

and its use in false medicines as well as its generation of artificial light. The image

included here, The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone,

Discovers Phosphorus (1770) is by Joseph Wright of Derby, via Wikimedia Commons. Read more about the discovery of phosphorus on the personal blog Res Obscura. - [TG]

Used by alchemists throughout the seventeenth century, phosphorous was

officially designated the thirteenth element by Antoine Lavosier in 1777. Quack

physicians incorporated the eerily-glowing phosphorous into their "cure all" medicines.

Here, Wollstonecraft may be referring to a long-standing association between the element

and its use in false medicines as well as its generation of artificial light. The image

included here, The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone,

Discovers Phosphorus (1770) is by Joseph Wright of Derby, via Wikimedia Commons. Read more about the discovery of phosphorus on the personal blog Res Obscura. - [TG]

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London. - [MUstudstaff]mahometanism

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London. - [MUstudstaff]mahometanism

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons. - [BT]education

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons. - [BT]education

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library. - [NB]trifling_employments

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library. - [NB]trifling_employments

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work. - [MM]history This is likely a reference to

discussions about the hierarchy of genres during the eighteenth century. Dorothee Birke,

author of Writing the Reader: Configurations of Cultural Practice in English Novel

(2016), explains that historical and philosophical works were seen to have

higher value than novels and poetry. The reason behind such a hierarchical placement is

the perception of fictional reading to be connected with ignorance as people are fed

unrealistic words. Thus, historical and philosophical works which were often based on

truth and it reality, were insightful readings that were ranked higher than unrealistic

or exaggerated works (Birke 63). - [DN]sandford_merton Likely a reference to a popular

children’s book written in the eighteenth century, Sandford and

Merton (1783), by Thomas Day, is about two boys who grow up differently based on

social status. According to

Stephen Bending and Stephen Bygrave, the book is an indictment of upper class

"effete" masculinity (23). Tommy Merton is spoiled by middle class privileges and needs

to be re-educated to become as fine a man as Sandford, whose lower-class status

challenged him to develop, physically and mentally, into an admirable young man (3-4).

Interested viewers can also read an abridged

version of Day’s children’s book, published in 1792, at the Internet Archive. - [SV]novelistsWollstonecraft's question refers to an

ongoing discussion about the work of novel-reading on young girls' intellectual growth.

It was thought dangerous for women to read novels because society feared that they would

not, as Anna North writes in "When Novels Were Bad for You," be able to "differentiate between fiction and

life." - [KS]bubbled

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work. - [MM]history This is likely a reference to

discussions about the hierarchy of genres during the eighteenth century. Dorothee Birke,

author of Writing the Reader: Configurations of Cultural Practice in English Novel

(2016), explains that historical and philosophical works were seen to have

higher value than novels and poetry. The reason behind such a hierarchical placement is

the perception of fictional reading to be connected with ignorance as people are fed

unrealistic words. Thus, historical and philosophical works which were often based on

truth and it reality, were insightful readings that were ranked higher than unrealistic

or exaggerated works (Birke 63). - [DN]sandford_merton Likely a reference to a popular

children’s book written in the eighteenth century, Sandford and

Merton (1783), by Thomas Day, is about two boys who grow up differently based on

social status. According to

Stephen Bending and Stephen Bygrave, the book is an indictment of upper class

"effete" masculinity (23). Tommy Merton is spoiled by middle class privileges and needs

to be re-educated to become as fine a man as Sandford, whose lower-class status

challenged him to develop, physically and mentally, into an admirable young man (3-4).

Interested viewers can also read an abridged

version of Day’s children’s book, published in 1792, at the Internet Archive. - [SV]novelistsWollstonecraft's question refers to an

ongoing discussion about the work of novel-reading on young girls' intellectual growth.

It was thought dangerous for women to read novels because society feared that they would

not, as Anna North writes in "When Novels Were Bad for You," be able to "differentiate between fiction and

life." - [KS]bubbled

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of

conduct books and their false depiction of women. "Bubbled" in this usage is also

derived from the devastating financial bubble in the eighteenth century, including the

South Sea Bubble of 1720. Many engravings and satirical prints of the time depict how

the people were deceived and cheated financially, most notably, The

Bubbler’s Medley, or a Sketch of the Times being Europe’s Memoriam for 1720.

The image included here is from the British Museum's online collection. To read more, visit Harvard Business School’s

online exhibit on the South Sea Bubble, and the source of this annotation. - [JMF]conduct

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of

conduct books and their false depiction of women. "Bubbled" in this usage is also

derived from the devastating financial bubble in the eighteenth century, including the

South Sea Bubble of 1720. Many engravings and satirical prints of the time depict how

the people were deceived and cheated financially, most notably, The

Bubbler’s Medley, or a Sketch of the Times being Europe’s Memoriam for 1720.

The image included here is from the British Museum's online collection. To read more, visit Harvard Business School’s

online exhibit on the South Sea Bubble, and the source of this annotation. - [JMF]conduct

Source: The Title page of Gregory's conduct book

This is most likely a reference to Dr. John Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, a conduct book written prior

to Dr. Gregory’s wife’s passing in 1761 and addressed to his daughters about etiquette,

religion, conduct, and behaviors. Wollstonecraft references this book directly in many

of her arguments. The image of the book's title page (1795) is from the University of Delaware Special Collections Department is from the National Library of Scotland. View a 1793 edition of A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters at the Internet

Archive. - [BT]johnson

Source: The Title page of Gregory's conduct book

This is most likely a reference to Dr. John Gregory’s A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, a conduct book written prior

to Dr. Gregory’s wife’s passing in 1761 and addressed to his daughters about etiquette,

religion, conduct, and behaviors. Wollstonecraft references this book directly in many

of her arguments. The image of the book's title page (1795) is from the University of Delaware Special Collections Department is from the National Library of Scotland. View a 1793 edition of A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters at the Internet

Archive. - [BT]johnson

Throughout the eighteenth century, St. Paul’s Church Yard was the center of the

publishing trade. Wollstonecraft's Vindications was published by

Joseph Johnson, a liberal publisher with radical views, who published work by William

Godwin, Joseph Priestly, and William Blake. Wollstonecraft lived near St. Paul’s Church

Yard and spent many hours in this workshop as Joseph Johnson gave her writing and

translating jobs throughout the day. For more on the relationship between Mary

Wollstonecraft and Joseph Johnson, see this letter from Wollstonecraft to her publisher reprinted in The

American Reader. The image here, from a University of Louisville news

article on William Shakespeare's first folio, shows the locations of printers around St.

Paul's during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. - [TH]elegance

Throughout the eighteenth century, St. Paul’s Church Yard was the center of the

publishing trade. Wollstonecraft's Vindications was published by

Joseph Johnson, a liberal publisher with radical views, who published work by William

Godwin, Joseph Priestly, and William Blake. Wollstonecraft lived near St. Paul’s Church

Yard and spent many hours in this workshop as Joseph Johnson gave her writing and

translating jobs throughout the day. For more on the relationship between Mary

Wollstonecraft and Joseph Johnson, see this letter from Wollstonecraft to her publisher reprinted in The

American Reader. The image here, from a University of Louisville news

article on William Shakespeare's first folio, shows the locations of printers around St.

Paul's during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. - [TH]elegance

Elegance in the 18th century has a specific meaning when applied to

women. According to Robert

W. Jones, author of Gender and the Formation of Taste in

Eighteenth-Century Britain, feminine elegance is the combination of

docility and enticement of men. In the eighteenth century, elegance is feminized with

the goal that women should use it to please and seduce men through beauty and

refinement. Elegance of the eighteenth century is the area of the pleasing and amiable

actions from women to men, these beauty standards were important and a source of

intrigue for the culture (Jones 109). The image here, drawn from the National Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC, shows An Elegant Lady Playing a Cittern (1770), by Nathaniel

Dance-Holland. - [SM]virtue Mary Wollstonecraft uses "virtue" with

its eighteenth-century sense of power. Men were often seen as virtuous because of their

physical strength, whereas women acquired virtue through sensibility and virginity.

Wollstonecraft argues that true virtue can only exist with knowledge and education.

Therefore, women must be properly educated or they would only be mimicking true virtue.

Views of Women in

Eighteenth Century Literature," published in the International

Journal of Communication Research by Adrian Brunello and Florina-Elena

Borsan reviews the way that understandings of womanhood shifted in the period, resulting

in the need for an exterior display of virtue, rather than true virtue (325-326). clicking here will direct you to the UK National Gallery of Art, showing An Allegory of Virtue and Riches, painted in 1667 by Godfried

Schalcken.

- [RB]schools

Elegance in the 18th century has a specific meaning when applied to

women. According to Robert

W. Jones, author of Gender and the Formation of Taste in

Eighteenth-Century Britain, feminine elegance is the combination of

docility and enticement of men. In the eighteenth century, elegance is feminized with

the goal that women should use it to please and seduce men through beauty and

refinement. Elegance of the eighteenth century is the area of the pleasing and amiable

actions from women to men, these beauty standards were important and a source of

intrigue for the culture (Jones 109). The image here, drawn from the National Gallery of

Art in Washington, DC, shows An Elegant Lady Playing a Cittern (1770), by Nathaniel

Dance-Holland. - [SM]virtue Mary Wollstonecraft uses "virtue" with

its eighteenth-century sense of power. Men were often seen as virtuous because of their

physical strength, whereas women acquired virtue through sensibility and virginity.

Wollstonecraft argues that true virtue can only exist with knowledge and education.

Therefore, women must be properly educated or they would only be mimicking true virtue.

Views of Women in

Eighteenth Century Literature," published in the International

Journal of Communication Research by Adrian Brunello and Florina-Elena

Borsan reviews the way that understandings of womanhood shifted in the period, resulting

in the need for an exterior display of virtue, rather than true virtue (325-326). clicking here will direct you to the UK National Gallery of Art, showing An Allegory of Virtue and Riches, painted in 1667 by Godfried

Schalcken.

- [RB]schools

The

most common schools available for lower working class families in eighteenth-century

were dame schools. An elderly, barely literate, woman would teach reading and sewing for

a small fee. Read more in English Heritage’s brochure on England’s School. The

image of children learning in a dame school, painted by Thomas Webster (1845), is housed

in the Tate Art Museum, London.

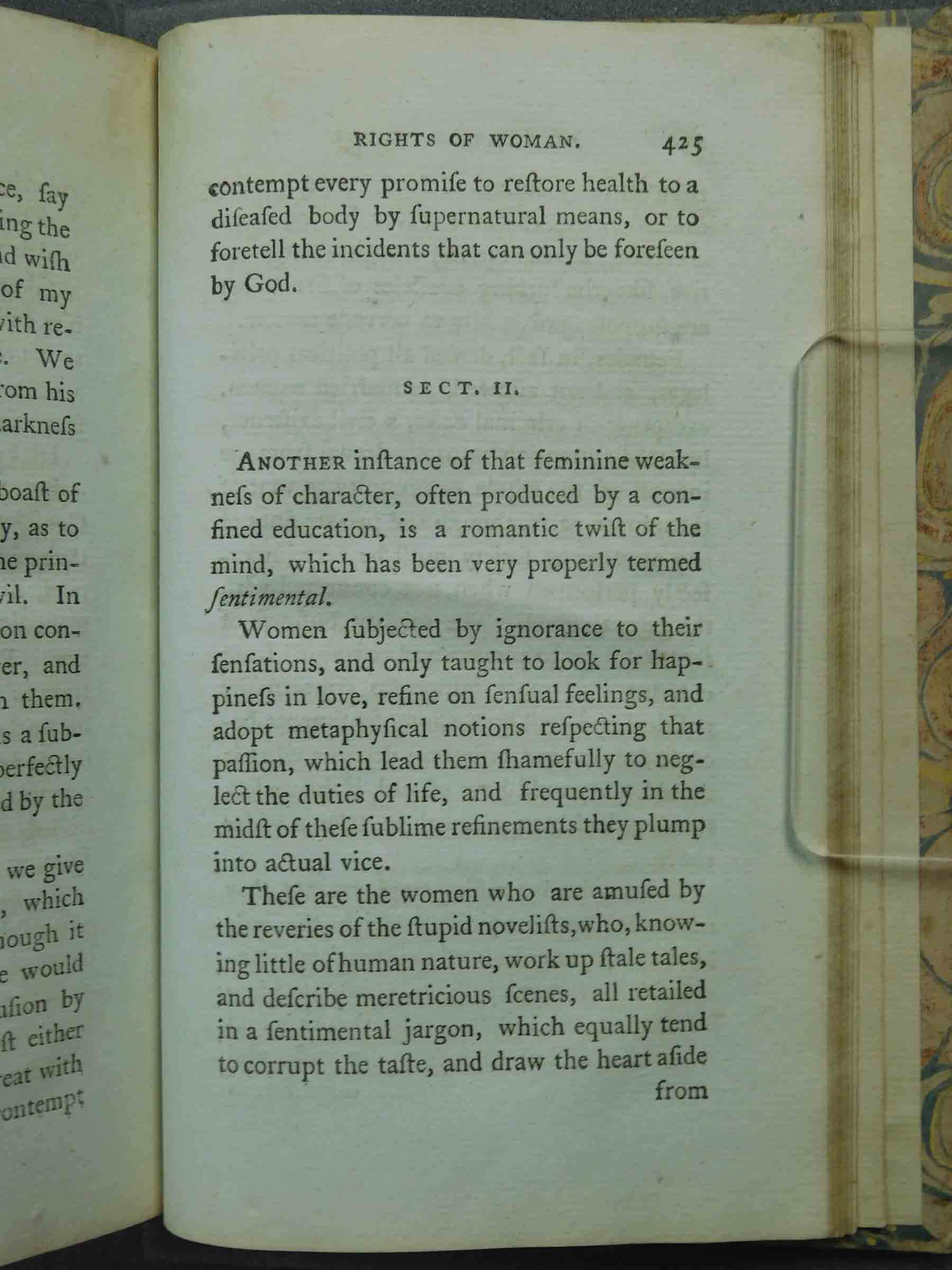

- [FB]sentimental The sentimental novel is a genre which

rose into popularity in the eighteenth century. This genre is characterized by

excessively passionate characters, tearful scenes and dramatic, flowery dialogue. Mary

Wollstonecraft may be using the popularity of these novels among young women to explain

their apparent lack of rationality rather than claiming irrationality to be a naturally

female trait. Read more about the sentimental novel in

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- [ES]novelsAs novels became more accessible they

became more popular. Some believed that excessive exposure to fiction novels would cause

readers to lose touch with reality and identify with characters to the point of

mimicking dangerous or immoral behavior. Read more about a popular novel that was blamed

for youthful suicides in this article by Frank Furedi from

History Today. - [ES]ranks The different ranks of society in

England during the eighteenth century were not simply divided between the rich or poor.

According to the eighteenth-century writer Daniel Defoe, there were seven categories:

the great, the rich, the middle sort, the working trades, the country people, the poor,

and the miserable. The country still relied on agriculture and, although some still died

of hunger, there was usually enough food to go around. Trade was increasing and more men

and women acquired jobs in industry. However, wealth was unequally distributed, with

only 5% of the national income belonging to the general population. Read more in this

Encyclopedia Britannica entry for eighteenth-century

Britain, and the source of this annotation. - [MR]seraglio

The

most common schools available for lower working class families in eighteenth-century

were dame schools. An elderly, barely literate, woman would teach reading and sewing for

a small fee. Read more in English Heritage’s brochure on England’s School. The

image of children learning in a dame school, painted by Thomas Webster (1845), is housed

in the Tate Art Museum, London.

- [FB]sentimental The sentimental novel is a genre which

rose into popularity in the eighteenth century. This genre is characterized by

excessively passionate characters, tearful scenes and dramatic, flowery dialogue. Mary

Wollstonecraft may be using the popularity of these novels among young women to explain

their apparent lack of rationality rather than claiming irrationality to be a naturally

female trait. Read more about the sentimental novel in

Encyclopedia Britannica.

- [ES]novelsAs novels became more accessible they

became more popular. Some believed that excessive exposure to fiction novels would cause

readers to lose touch with reality and identify with characters to the point of

mimicking dangerous or immoral behavior. Read more about a popular novel that was blamed

for youthful suicides in this article by Frank Furedi from

History Today. - [ES]ranks The different ranks of society in

England during the eighteenth century were not simply divided between the rich or poor.

According to the eighteenth-century writer Daniel Defoe, there were seven categories:

the great, the rich, the middle sort, the working trades, the country people, the poor,

and the miserable. The country still relied on agriculture and, although some still died

of hunger, there was usually enough food to go around. Trade was increasing and more men

and women acquired jobs in industry. However, wealth was unequally distributed, with

only 5% of the national income belonging to the general population. Read more in this

Encyclopedia Britannica entry for eighteenth-century

Britain, and the source of this annotation. - [MR]seraglio

Wollstonecraft’s argument in A Vindication of the

Rights of Woman is that women spend most of their lives acquiring knowledge to

be perfect wives instead of strengthening their minds and bodies to place a man. Because

the only way women can rise the world is through marriage, they are being groomed to

become lovers much like women in a Turkish seraglio, as Susan Gubar notes in "Feminist

Misogyny" (Gubar

151). Wollstonecraft is pointing out the lack of freedom for women. The image

included here illustrates the women’s quarter of a seraglio painted in 1873 by John

Frederick Lewis. This image is from Wikimedia Commons.

- [RDJ]dress

Wollstonecraft’s argument in A Vindication of the

Rights of Woman is that women spend most of their lives acquiring knowledge to

be perfect wives instead of strengthening their minds and bodies to place a man. Because

the only way women can rise the world is through marriage, they are being groomed to

become lovers much like women in a Turkish seraglio, as Susan Gubar notes in "Feminist

Misogyny" (Gubar

151). Wollstonecraft is pointing out the lack of freedom for women. The image

included here illustrates the women’s quarter of a seraglio painted in 1873 by John

Frederick Lewis. This image is from Wikimedia Commons.

- [RDJ]dress

In the eighteenth century, women were encouraged to focus on their

dress, meaning their overall attire, because as Dr. Gregory argues in A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, it was supposedly natural

to them (55). Women were dressed in hope of catching the attention of a man;

they would parade, or flaunt themselves to men, hoping to find a husband, which is the

only way for a woman to "rise in the world," as Wollstonecraft notes above (9).

Wollstonecraft didn’t want women to dress and flaunt themselves only for men’s

attention; she wanted women to focus on their own education. This portrait of Madame

Pompadour, located in the Alte Pinkothek Museum in Munich and via Wikimedia Commons, provides an example of

women’s attire in the 1700s in which Wollstonecraft was advising them not to do. Learn

more about eighteenth-century fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum. - [DF]governess According to Katheryn Hughes, the governess was one of the most familiar figures in the

Romantic period and throughout the Victorian period. Governesses were women who earned

their living by teaching and caring for other women’s children. Most governesses lived

with their employers and were paid a small salary on top of their board and lodging. The

governess was seen as an outsider, not quite fitting in with the family she governed for

but not exactly fitting in as a servant either. - [AH]manly

In the eighteenth century, women were encouraged to focus on their

dress, meaning their overall attire, because as Dr. Gregory argues in A Father’s Legacy to His Daughters, it was supposedly natural

to them (55). Women were dressed in hope of catching the attention of a man;

they would parade, or flaunt themselves to men, hoping to find a husband, which is the

only way for a woman to "rise in the world," as Wollstonecraft notes above (9).

Wollstonecraft didn’t want women to dress and flaunt themselves only for men’s

attention; she wanted women to focus on their own education. This portrait of Madame

Pompadour, located in the Alte Pinkothek Museum in Munich and via Wikimedia Commons, provides an example of

women’s attire in the 1700s in which Wollstonecraft was advising them not to do. Learn

more about eighteenth-century fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum. - [DF]governess According to Katheryn Hughes, the governess was one of the most familiar figures in the

Romantic period and throughout the Victorian period. Governesses were women who earned

their living by teaching and caring for other women’s children. Most governesses lived

with their employers and were paid a small salary on top of their board and lodging. The

governess was seen as an outsider, not quite fitting in with the family she governed for

but not exactly fitting in as a servant either. - [AH]manly

"Manly virtues" in the eighteenth century refers to social

behavior that encourages men to be kind, loving, and courageous both in the home and in

the public domain. Since masculinity is, as Intertextual War: Edmund

Burke and the French Revolution in the Writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Paine,

and James Mackintosh by Steven Blakemore, states, a "restrictive misnomer for

qualities or virtues that are human," Mary Wollstonecraft opposes men that inveigh

against masculine women because of its imitation of manly virtues (Blakemore 42). The portrait here, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

by Thomas Gainsborough (1748), is housed in the National Gallery London. This painting,

via Wikimedia Commons, illustrates manliness in terms of gentility. - [RB]phosphorus

"Manly virtues" in the eighteenth century refers to social

behavior that encourages men to be kind, loving, and courageous both in the home and in

the public domain. Since masculinity is, as Intertextual War: Edmund

Burke and the French Revolution in the Writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Paine,

and James Mackintosh by Steven Blakemore, states, a "restrictive misnomer for

qualities or virtues that are human," Mary Wollstonecraft opposes men that inveigh

against masculine women because of its imitation of manly virtues (Blakemore 42). The portrait here, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

by Thomas Gainsborough (1748), is housed in the National Gallery London. This painting,

via Wikimedia Commons, illustrates manliness in terms of gentility. - [RB]phosphorus

Used by alchemists throughout the seventeenth century, phosphorous was

officially designated the thirteenth element by Antoine Lavosier in 1777. Quack

physicians incorporated the eerily-glowing phosphorous into their "cure all" medicines.

Here, Wollstonecraft may be referring to a long-standing association between the element

and its use in false medicines as well as its generation of artificial light. The image

included here, The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone,

Discovers Phosphorus (1770) is by Joseph Wright of Derby, via Wikimedia Commons. Read more about the discovery of phosphorus on the personal blog Res Obscura. - [TG]

Used by alchemists throughout the seventeenth century, phosphorous was

officially designated the thirteenth element by Antoine Lavosier in 1777. Quack

physicians incorporated the eerily-glowing phosphorous into their "cure all" medicines.

Here, Wollstonecraft may be referring to a long-standing association between the element

and its use in false medicines as well as its generation of artificial light. The image

included here, The Alchymist, In Search of the Philosopher’s Stone,

Discovers Phosphorus (1770) is by Joseph Wright of Derby, via Wikimedia Commons. Read more about the discovery of phosphorus on the personal blog Res Obscura. - [TG][TP]

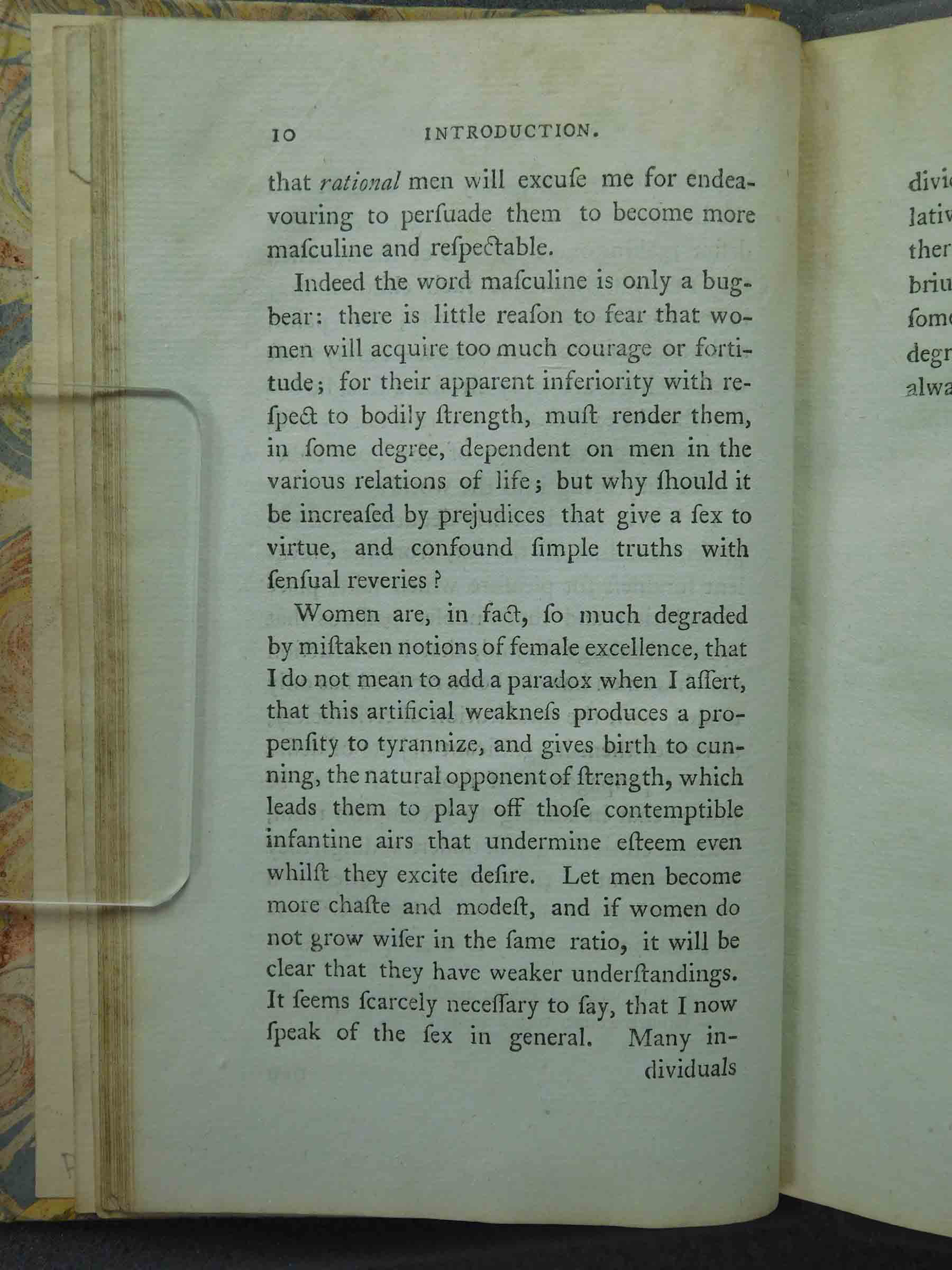

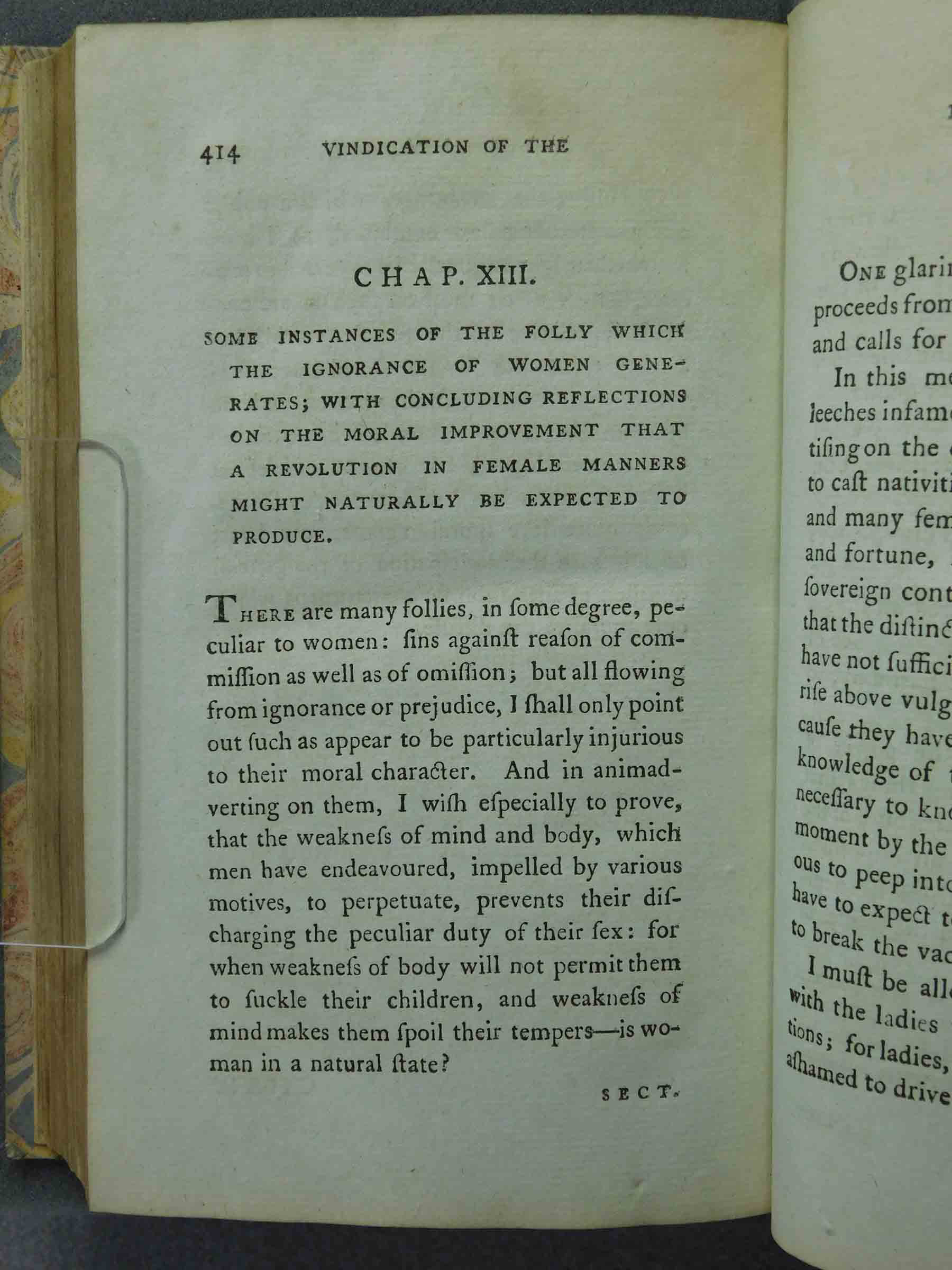

A

VINDICATION

OF THE

RIGHTS OF WOMAN:

WITH

STRICTURES

ON

POLITICAL AND MORAL SUBJECTS

BY MARY WOLLSTONECRAFTwollstonecraft

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR J. JOHNSON, No.71, ST. PAUL’S CHURCH YARD.johnson

1792.

A

VINDICATION

OF THE

RIGHTS OF WOMAN:

WITH

STRICTURES

ON

POLITICAL AND MORAL SUBJECTS

BY MARY WOLLSTONECRAFTwollstonecraft

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR J. JOHNSON, No.71, ST. PAUL’S CHURCH YARD.johnson

1792.

Footnotes

wollstonecraft_

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Born in London on April 27, 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is considered

one of the principal figures in modern feminism. Her works reflected her unmarried

middle class experience, emphasizing gender injustice, the failure of the education

system for young women, and the position of women in unhappy marriages. Her best known

work, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), argues that to

attain virtue, women need access to systemic education. See this biographical essay on Wollstonecraft by Janet Todd. The portrait of

Wollstonecraft included here, painted by John Opie (1797), is housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London. mahometanism_

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons.

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons.

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons.

Source: 1848 lithograph by James Rattray showing an Afgan women under purdahA term used by Westerners to refer to Muslims, in this context

Mahometanism is associated with the limited opportunities and oppressed status of women

in the eighteenth century. As discussed in The

Feminization Debate in Eighteenth-Century England (2004) by E. Clery,

women were trained to obey their father and husband. This confinement and

domesticization was frequently described as "Mahometan" due to the misguided belief

among the English that Islam sees women as not possessing souls. Social reformer and

leader of the Blue Stockings Society, Elizabeth Montagu lamented in a letter about the

effects of such "Mahometan" belief, which is used to justify women's domestic

confinement (Clery 136). The image included here, an 1848 lithograph by James Rattray, shows

Afgan women under purdah. Image via

Wikimedia Commons.education_

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library.

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library.

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library.

Mary Wollstonecraft noted the absence of proficient education for

young women in the eighteenth century and decided to establish a school. Wollstonecraft,

along with her sister Eliza, and friend Fanny Blood, opened the school in 1784. The

school was established in Newington Green just outside of London. Although the school

closed from financial distress in 1785, Wollstonecraft drew from her experience as a

teacher and wrote Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with

Reflections on Female Conduct in the more important Duties of Life (1787). The

above picture shows a plaque dedicated to Mary Wollstonecraft at the Newington Green

Primary School near where the school was located in the 18th century. For more

information on the life of Mary Wollstonecraft, read this biographical essay

written by Sylvana Tomaselli. To look through a copy of Wollstonecraft's Thoughts on the Education of Daughters with Reflections on Female

Conduct in the more important Duties of Life click here for an

online version of the book from the London School of Economics’ digital library. trifling_employments_

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work.

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work.

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work.

By "trifling employments," Wollstonecraft refers to the kinds of

things elegant women did to employ their time such as needlepoint. Not allowed to

participate in the masculine public sphere, women instead spent their time in domestic

labor and activities. Many were mothers and homemakers. These activities were not

masculine and serious but feminine and trifling. Read more on women’s work in the

eighteenth century in this article by

Susan E. Jones, also the source of this annotation. The portrait above, via the Frick

Collection, is a conversation piece by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) showing the

genteel young ladies Waldegrave engaged in such domestic work. history_ This is likely a reference to

discussions about the hierarchy of genres during the eighteenth century. Dorothee Birke,

author of Writing the Reader: Configurations of Cultural Practice in English Novel

(2016), explains that historical and philosophical works were seen to have

higher value than novels and poetry. The reason behind such a hierarchical placement is

the perception of fictional reading to be connected with ignorance as people are fed

unrealistic words. Thus, historical and philosophical works which were often based on

truth and it reality, were insightful readings that were ranked higher than unrealistic

or exaggerated works (Birke 63).

sandford_merton_ Likely a reference to a popular

children’s book written in the eighteenth century, Sandford and

Merton (1783), by Thomas Day, is about two boys who grow up differently based on

social status. According to

Stephen Bending and Stephen Bygrave, the book is an indictment of upper class

"effete" masculinity (23). Tommy Merton is spoiled by middle class privileges and needs

to be re-educated to become as fine a man as Sandford, whose lower-class status

challenged him to develop, physically and mentally, into an admirable young man (3-4).

Interested viewers can also read an abridged

version of Day’s children’s book, published in 1792, at the Internet Archive.

novelists_Wollstonecraft's question refers to an

ongoing discussion about the work of novel-reading on young girls' intellectual growth.

It was thought dangerous for women to read novels because society feared that they would

not, as Anna North writes in "When Novels Were Bad for You," be able to "differentiate between fiction and

life."

bubbled_

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of

conduct books and their false depiction of women. "Bubbled" in this usage is also

derived from the devastating financial bubble in the eighteenth century, including the

South Sea Bubble of 1720. Many engravings and satirical prints of the time depict how

the people were deceived and cheated financially, most notably, The

Bubbler’s Medley, or a Sketch of the Times being Europe’s Memoriam for 1720.

The image included here is from the British Museum's online collection. To read more, visit Harvard Business School’s

online exhibit on the South Sea Bubble, and the source of this annotation.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the eighteenth-century

the word "bubbled" meant befooled, cheated, or deceived. Here, Wollstonecraft is saying

women’s understandings have been fooled by the popularization and distribution of