"Satyr [Against Reason and Mankind]"

By

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students and Staff of Marymount University, Jordan Lawton

[TP]

POEMS

ON SEVERAL

OCCASIONS

Printed at ANTWERP,Antwerp Antwerp 'Antwerp’ is a false imprint. James Thorpe discusses this interesting detail in The Earliest Editions of Rochester’s Poems" noting that the printings were “unlicensed books printed in London” where the false imprint was used for “simple subterfuge presumably intended to attract the lovers of racy literature or distract prosecution”. - [JL] 1690.

6 SATYR [AGAINST REASON AND MANKIND]

1WEre I (who to my cost already am 2One of those strange prodigious Creatures Man.) 3A Spirit free, to choose for my own share, 4What case of Flesh, and Blood, I pleas'd to wear, 5I'd be a Dog, a Monkey, or a Bear. 6Or any thing but that vain Animal, 7Who is so proud of being rational. 8The senses are too grossgross, and he'll contrive grossIn this sense, gross refers to materiality as distinct from ethereality or spirituality. See OED adj III.8.c: describes "things material or perceptible to the senses, as contrasted with what is spiritual, ethereal, or impalpable." - [MUStudStaff] 9A Sixth, to contradict the other Five; 10And before certain instinct, will preferr 11Reason, which Fifty times for one does err. 7 12Reason, an Ignis fatuus,ignus-fatuusignus-fatuusFrom the Latin meaning, literally, "foolish fire," an ignis fatuus is a will-o'the-wisp, a flitting phosphorescent light that led travelers astray in marshy areas like the "Fenny Bogs and Thorny Brakes" (15) Rochester describes below (OED, "ignis fatuus, n."). - [JL] in the Mind, 13Which leaving light of Nature, sense behind; 14Pathless and dan'grous wandring ways it takes, 15Through errors, Fenny-Boggs, and Thorny Brakes; 16Whilst the misguided follower, climbs with pain, 17Mountains of Whimseys, heap'd in his own Brain: 18Stumbling from thought to thought, falls headlong down, 19Into doubts boundless Sea, where like to drown. 20Books bear him up awhile, and makes him try, 21To swim with Bladders of Philosophy; 22In hopes still t'oretake th'escaping light, 23The Vapour dances in his dazling sight, 24Till spent, it leaves him to eternal Night. 25Then Old Age, and experience, hand in hand, 26Lead him to death, and make him understand, 27After a search so painful, and so long, 28That all his Life he has been in the wrongwrong; wrongLines 29-36 explain how, from Rochester's perspective, this approach to life that prizes reason is "in the wrong." - [TH] 29Hudled in dirt, the reas'ning Engine lyes,reason reasonThe "reasoning Enging" is the mind--here, Rochester notes that the mind is "huddled in [the] dirt" of the physical body. The body and the mind are intertwined, rather than separate. - [TH] 30Who was so proud, so witty, and so wise, 31Pride drew him in, as Cheats, their Bubblesbubbles, catch, bubblesHere used as a noun, "bubbles" in this sense refers to those who have been fooled or cheated (OED, n.2b). - [TH] 32And makes him venture, to be made a Wretch. 33His wisdom did his happiness destroy, 34Aiming to know what World he shou'd enjoy; 35And Wit, was his vain frivolous pretence, 36Of pleasing others, at his own expence. 37For Wittswitswits During the Restoration period in England, Charles II would often be found in the company of young intellectuals or "wits." In The Court Wits of the Restoration, John Harold Wilson writes that “the label Wit was attached only to one who made some real pretense to distinction as a poet, critic, translator, raconteur, or a man of learning" (6). Among the so-called "court wits" were Rochester, Sir John Suckling, Edmund Waller, and others. [add paraphrase from page 5 of Tilmouth: https://books.google.com/books?id=DipmhwkFfQMC - [JL] are treated just like common Whores, 38First they're enjoy'd, and then kickt out of Doores, 39The pleasurepleasure past, a threatning doubt remains, pleasureAs Jeremy Webster argues in Performing Libertinism in Charles II’s Court, “[l]ibertines...performed traditionally secretive acts— excessive drinking, carnality, sodomy, sedition, assault, and sacrilege—in the public sphere in a variety of ways” (2). Here, Rochester is talking in part about sexual pleasure that, once enjoyed, brings causes the enjoyer to fear or hate that pleasure. This fear is in part existential or philosophical--pleasure brings with it "dang'rous" (41) questions about the value of social order founded on reason--but it is also material, as in the fear of sexually transmitted infection, from which Rochester sufferred. The "succeeding pains" (40) to which he refers encapsulate both kinds of fears. - [TH] 40That frights th'enjoyer, with succeeding pains: 41Women and Men of Wit, are dang'rous Tools, 42And ever fatal to admiring Fools. 8 43Pleasure allures, and when the FoppsfopsfopsIn "Fops and Some Versions of Foppery," Robert B. Heilman discusses this term, noting that as a “general, all-purpose carrier of disapproval, fop works much like fool" (364). - [JL] escape, 44'Tis not that they're belov'd, but fortunate, 45And therefore what thy fear, at least they hate. 46But now methinks some formal Band, and Beard,bandband According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

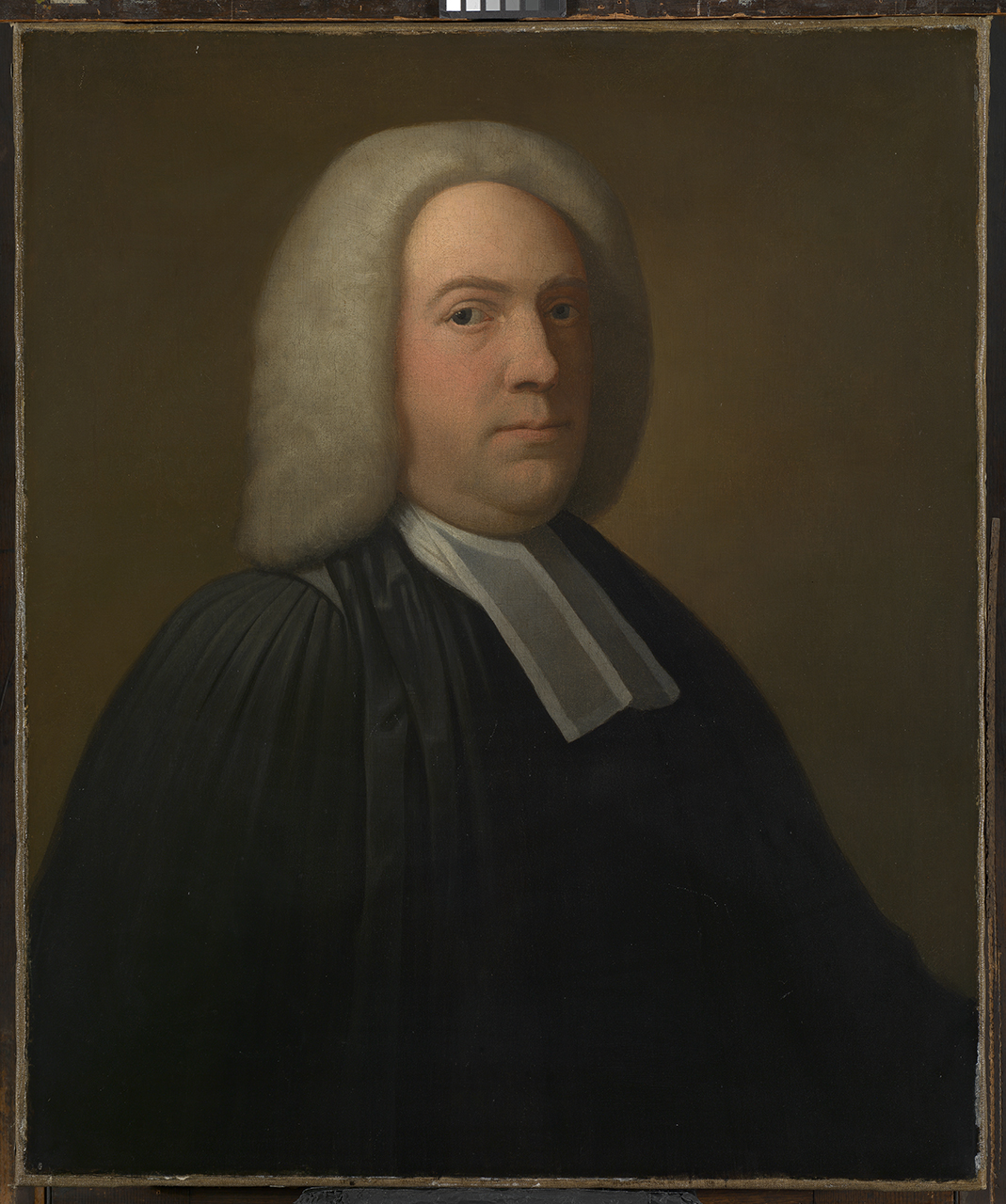

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

) - [JL]

47Takes me to task, come on Sir I'm prepar'd.

48Then by your favour, any thing that's

writ

49Against this gibeing jingling knack call'd Wit,

50Likes me abundantly, but you take care,

51Upon this point, not to be too severe.

52Perhaps my Muse, were fitter for

this part,

53For I profess, I can by very smart

54On Wit, which I abhor with all my

heart:

55I long

to lash it in some sharp Essay,libertinism

libertinismFor Margaret Ezell,

who writes about the performative quality of Restoration libertinism, Rochester's

libertinism was a deliberate assertion of privilege designed to cultivate power in

the court ("Enacting Libertinism: Court Performance and Literary Culture" in The Oxford English Literary History, Vol. V.). Rochester's

poem is a response to the question being asked here by a hypothetical clergyman

(the "formal band and beard"). Here, he is performing the persona of the pedantic,

prudish curate ultimately to mock him and his moral philosophy, thereby

cultivating a witty superiority.

56But your grand indiscretion bids me stay,

57And turns my Tide of Ink another way.

58What rage ferments in

your degen'rate mind,rage

59To make you rail at Reason, and Mankind?

rageThe

clergyman describes Rochester's mind as "degen[e]rate," and his way of thinking,

deviant. Rochester’s poem is a “Satire against Reason and Mankind”; it is

fundamentally skeptical of the ability--or desirability--of reason and law to

ameliorate baser human interests. - [TH]

60Bless glorious Man! to whom alone

kind Heav'n,

61An everlasting Soul has freely

giv'n;

62Whom his great Maker took such

care to make,

63That from himself he did the Image take;

64And this fair frame, in shining Reason drest,

65To dignifie his Nature, above

Beast.

66Reason, by whose aspiring influence,

67We take a flight beyond material sense.

68Dive into Mysteries, then soaring pierce,

69The flaming limits of the Universe.

70Search Heav'n and Hell, find out what's acted

there,

71And give the World true grounds of hope and

fear.

72Hold mighty Man, I

cryspeaker, all this we know,

speakerAt this point, Rochester's character speaks,

returning a satirical answer to the pedantic curate.

73From the Pathetique Pen of Ingello;Ignello

Ignello

Nathaniel

Ingelo, born ca 1621. Graduate and fellow of the Queen’s College,

Cambridge. Ingelo was a clergyman and author of a religious romance entitled Bentivolio and Urania. Marianne Thormählen writes in aRochester: The Poems in Context that the works of Ingelo and Simon

Patrick mentioned below would have been well known during Rochester’s time. She

mentions that Rochester would have detested “Ingelo’s exalted view of man; and his

attacks on Epicurus and his followers”.

9

74From P—

Pilgrimp,pSimon Patrick, Bishop of Ely (1626-1707) was an English

theologian and, eventually, bishop; his book The Parable of

the Pilgrim (1663/4) is referenced here. Patrick's Pilgrim is an allegory along the same lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Patrick’s first assignment after

graduating from Queen's College, Cambridge, was as a domestic chaplain to Sir

Walter St. John, John Wilmot’s uncle (Dictionary of National Biography)> - [TH]

S— replyss,

sRichard Sibbes

(1577-1635), was a popular Puritan theologian, minister, and writer, in the

affective tradition with intellectual connections to Calvinism. He is most well

known for a work called The Bruised Reed, but Rochester

here references a work this editor has not been able to trace. Other editions of

the poem replace "replies" with "soliloquies," possibly suggesting a different

work, Richard Bayne's Holy Soliloquies (1637)--Sibbes wa

very influenced by Bayne. Regardless, all of these references are to popular

theologians during the 17th century. . He, too, studied at Cambridge, but his

Puritanism caused him to lose a lectureship there (Dictionary of National Biography). - [TH]

75And 'tis this very reason I despise.

76This supernatural gift, that makes a Myte-,

77Think he is the Image of the Infinite:

78Comparing his short life, void of all rest,

79To the Eternal, and the ever blest.

80This busie, puzling, stirring up of doubt,

81That frames deep Mysteries, then finds 'em out;

82Filling with Frantick Crowds of thinking Fools,

83Those Reverend Bedlamsbedlam, Colledges, and Schools

bedlamBedlam is

the colloquial term for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, an asylum for the

mentally ill first established in 1676. It was often used as a broader term for

any location of perceived insanity. - [TH]

84Borne on whose Wings, each heavy Sotsot can pierce,

sotA sot is a stupid

person, usually someone who is "stupified" with liquor or habitually drunk

(OED). - [TH]

85The limits of the boundless Universe.

86Socomparison charming Oyntments,

make an Old Witch flie,

comparisonRochester compares the inflated ideology of the pedantic curate--whose "business"

is "Nonsense" and "impossibilities" (86)--with the superstitions that give witches

the power of flight. - [TH]

87And bear a Crippled Carcass through the Skie.

88'Tis this exalted pow'rpower, whose

bus'ness lies,

powerRochester

refers here to reason as the falsely "exalted pow'r." The remainder of the poem

will lay out why the poet thinks so. - [TH]

89In Nonsense, and impossibilities.

90This made a Whimsical Philosopher,

91Before the spacious World, his Tubtub prefer

tubThe word tub has a lot of meanings during this period. Proverbially,

it is used to refer to a fiction, or a made-up story; but it also specifically

refers to the pulpit from which a non-conformist preacher spoke. Nonconformity

refers to any religious faith not strictly Anglican. It also has another meaning

that

Rochester would have known about--a "sweating-tub" or a sort of barrel

encasing the

body used specifically to treat venereal disease. See the

OED. - [TH]

92And we have modern Cloysterd Coxcombs, who

93Retire to think, cause they have naught to do.

94But thoughts, are giv'n for Actions government,

95Where Action ceases, thoughts impertinent:

96Our Sphere of

Action, is lifes happiness,action

actionRochester became identified with philosophical and sexual libertinism of the

Restoration, which was characterized by the public, even performative pursuit of

pleasure and a vivid, almost nihilistic sexuality. Libertinism was underpinned by

a selective reading of Thomas Hobbes' theory of human nature. Hobbes, according to

Christopher Tilmouth, "declar[ed] that the passions, not reason, constituted the

proper, primary determinants of human conduct" and "posited...a new ideal of

happiness, equating felicity with a constant motion of the self from the

satisfaction of one appetite to the next, and he accorded fear and the lust for

power critical roles in this kinetic process" (Tilmouth 4-5).

Hobbes

characterized humankind in nature as in a permanent state of conflict and

struggle, governed by their appetites and their passions, and to avoid this

chaotic, violent state of nature, human societies contract with strong leaders to

bring order to passion and law to desire: "it is manifest that, during the time

men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that

condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every

man" (Leviathan, XIII, para. 8). Rochester positions his

libertinism as a moral freedom beyond the civil codes of contractual law. For more

on Restoration libertinism, see James Turner, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London, especially

chapter 6; and Diane Maybank'sarticle for the British Library about libertinism on the

Restoration stage. - [TH]

97And he who thinks Beyond, thinks like an Ass.

98Thus, whilst' gainst false reas'ning I inveigh,

99I own right Reason, which I wou'd obey:

100That Reason

that distinguishes by sensereasons,

reasonsRochester compares his materialist sense of reason--reason that rightly

"distinguishes by sense [perception]"--to the flawed or "false" reason of the

pedantic curate, that starts with the "beyond" (97). - [TH]

101And gives us Rules, of good, and ill from

thence:

102That bounds desires, with a reforming Will,

103To keep 'em more in vigour, not to kill.

104Your Reason hinders, mine helps t'enjoy,

105Renewing Apetites, yours wou'd destroy.

10

106My Reasons is my Friend, yours is a Cheat,

107Hungar call's out, my Reason bids me eat;

108Perversly yours, your Appetite does mock,

109This askt for Food, that answers what's a Clock?

110This plain distinction Sir your doubt secures,

111'Tis not true Reason I despise but yours.

112This I think Reason righted, but for Man,

113I'le nere recant defend him if you can.

114For all his Pride, and his Philosophy,

115'Tis evident, Beasts are in their degree,

116As wise at least, and better far than he.

117Those Creatures, are the wisest who attain,

118By surest means, the ends at which they aim.

119If therefore Jowlerjowler, finds, and Kills his Hares,

jowlerA common

name for a dog. - [TH]

120Better than M—m,

supplyes Committed Chairs;

mM-- is Henry

More, a rationalist Cartesian theologian who argues that God orders the world

infallibly and always according to the best ends ("the best of all possible

worlds"). He wrote several books, including On the Immortality

of the Soul, where he sought to counter the Hobbesian view of life outside

of society as "nasty, brutish, and short" and instead to prove "the exsitence of

immaterial substance, or spirit, and therefore God" (Stanford Encyclopedia

of Philosophy); he is most well known for his idea of the Spirit of

Nature, which connected the material world to the spiritual. Like other Platonists

of the 17th century, he believed that the immortality of the soul proved an

afterlife, characterized by damnation or salvation. Rochester disagreed with this

perspective. - [TH]

121Though one's a Sates-man, th'other but a Hound.

122Jowler, in Justice, wou'd be wiser found.

123You see how far Mans wisedom here extends,

134Look next, if humane Nature makes amends;

125Whose Principles, most gen'rous are, and just,

126And to whose Morals, you wou'd sooner trust.

127Be Judge your self, I'le bring it to the test,

128Which is the basest Creature Man, or Beast?beasts

beastsIn the

following lines, Rochester sets up an extended comparison between the nature of

violence in the animal kingdom and in the human world. - [TH]

129Birds feed on Birds, Beast

on each other prey,

130But Savage Man alone, does Man betray:

131Prest by necessity, they Kill for Food,

132Man, undoes Man, to do

himself no good.

133With Teeth, & Claws: by Nature arm'd thy hunt,

134Natures allowance, to supply their want.

135But Man, with smiles, embraces Friendships,

praise.

136Unhumanely his Fellows life betrays;

11

137With voluntary pains, works his distress,

138Not through necessity, but wantonness.

139For hunger, or for Love, they fight, or tear,

140Whilst wretched Man, is still in Arms for fear;

141For fear he Armes, and is of Armes afraid,

142By fear, to fear, successively betray'd

143Base fear, the fource whence his best passion came,

144His boasted Honour, and his dear bought Fame.

145That lust of Pow'r, to which he's such a Slave,

146And for the which alone he dares be brave:

147To which his various Projects are design'd,

148Which makes him gen'rous, affable, and kind.

149For which he takes such pains to be thought wise,

150And screws his actions, in a forc'd disguise:

151Leading a tedious life in Misery,

152Under laborious, mean Hypocrisie.

153Look to the bottom, of his vast design,

154Wherein Mans Wisdom, Pow'r, and Glory joyn;

155The good he acts, the ill he does endure;

156'Tis all for fear, to make himself secure.

157Meerly for safety, after Fame we thirst,

158For all Men, wou'd be Cowards if they durst.

159And honesty's against all common sense,

160Men must be Knaves, 'tis in

their own defence.

161Mankind's dishonest, if you think it fair;

162Amongst known Cheats,

to play upon the squaresquare,

square"To play

upon the square" means to play fairly (or "fair and square," in current colloquial

terms). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this expression was "[v]ery

common from c1670, frequently with reference to...gaming" ("square," adj.,

III.12.b). - [TH]

163You'le be undone -----

-------dashes

dashesDuring this period, dashes were often used to

visibly omit a name that would identify the subject of satire. Usually,

contemporary readers would have understood who the author was referring to.

164Nor can weak truth, your reputation save,

165The Knaves, will all agree to call you Knave.

166VVrong'd shall he live, insulted o're, opprest.

167VVho dares be less a Villain, than the rest.

12

168Thus Sir you see what humane Nature

cravesnature,

natureIn Leviathan (1651), Hobbes argued that humans are completely

driven by the primary drives of appetite and aversion; people are selfish at their

root. In the state of nature, which is a state of war, “there is no place for

industry...; no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is

worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man

solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Paragraph 9, Chapter 13, Leviathan). - [TH]

169Most Men are Cowards, all Men shou'd be Knaves:

170The diff'rence lyes (as far as I can see)

171Not in the thing it self, but the degree;

172And all the subject matter of debate,

173Is only who's a Knave, of the first Rate?

174All this with indignation have I hurl'd,

175At the pretending part of the proud World,

176Who swolne with selfish vanity, devise,

177False freedoms, holy Cheats, and formal Lyes

178Over their fellow Slaves,slaves to tyrannize.

slavesRochester suggests that "the pretending part of the proud World" (175) use their

supposed spiritual superiority to weild tyrranical power over other people, not

recognizing that everyone is a "Slave." - [TH]

179But if in Courtcourt, so just a Man there be,

courtCourt

here, as elsewhere, refers to the court of nobles and other people of power

surrounding King Charles II (or whomever was monarch at the time). Court culture,

in the Restoration, was often characterized both by stringent absolutism and a

permissiveness that distinguished those of privilege. To read more about

Restoration court culture, see Culture and Politics at the Court of Charles II,

1660-1685, by Matthew Jenkinson. - [TH]

180(In Court, a just Man, yet unknown to me.)

181Who does his needful flattery direct,

182Not to oppress, and ruine, but protect;

183Since flattery which may so ever laid,

184Is still a Tax on that unhappy Trade.

185If so upright a States-Man, you can find,

186Whose passions bend to his unbyas'd Mind;

187Who does his Arts, and Policies apply,

188To raise his Country, not his Family;

189Nor while his Pride, own'd Avarice withstands,

190Receives Aurealaureal Bribes, from

Friends corrupted hands.

aurealReaders may

be more familiar with the noun form ("aura") of this obsolete adjective. "Aureal

Bribes" are bribes that are gilded or golden (OED). - [TH]

191Is there a Church-Man who on God relyes?

192Whose Life, his Faith, and Doctrine Justifies?

193Not one blown up, with vain Prelatique Pride,

194Who for reproof of Sins, does Man deride:

195Whose envious heart with his obstrep'ous sawcy Eloquence,

196Dares chide at Kings, and raile at Men of

sense.

13

197Who from his Pulpit, vents more peevish lies,

198More bitter railings, scandals, Calumnies,

199Than at a Gossipping, are thrown about,

200When the good Wives get drunk, and then fall

out.

201None of that sensual Tribe, whose Talents lye,

202In Avarice, Pride, Sloth, and Gluttony.

203Who hunt good Livings, but abhor good Lives,

204Whose lust exalted, to that height arrives,

205They act Adūltery with their own Wives.

206And e're a score of years compleated be,

207Can from the lofty Pulpit proudly see,

208Half a large Parish, their own Progeny.

209Nor doating B—b who wou'd be ador'd,

bOther versions of Rochester's poem

replace the initial with "bishops."

210For domineering at the Councel Board;

211A greater Fop, in business at fourscorefourscore,

fourscoreA unit

of measurement, usually of time. A "score" is twenty; so, four score is four times

twenty, or eighty. - [TH]

212Fonder of serious Toyes, affected more,

213Than the gay glitt'ring Fool, at twenty proves,

214With all his noise, his tawdrey Cloaths, and loves,

215But a meek humble Man, of modest sense,

216Who Preaching peace, does practice continence;

217Whose pious life's a proof he does believe,

218Misterious truths, which no Man can conceive.

219Ifif upon Earth

there dwell such God like Men,

ifRochester here

makes an IF/THEN logical statement. If such "[in]conceiv[ably]" (218) "meek humble

M[e]n, of modest sense" (215) can be revealed, he'll "recant" (220) this poetic

statement. - [TH]

220I'le here recant my Paradox to them.

221Adore those Shrines of Vertue,

Homage pay,

222And with the Rabble Worldrabble, their Laws obey.

rabble"Rabble" here is used as a

derogatory term to refer to the masses or the common people--and "their Laws"

(222)--from which mob Rochester distances himself through his libertinism. See the

OED "rabble," n.1 and adj., particularly sense 3.

223If such there are, yet grant me this at least,

224Man differs more from Man,

than Man from Beast.

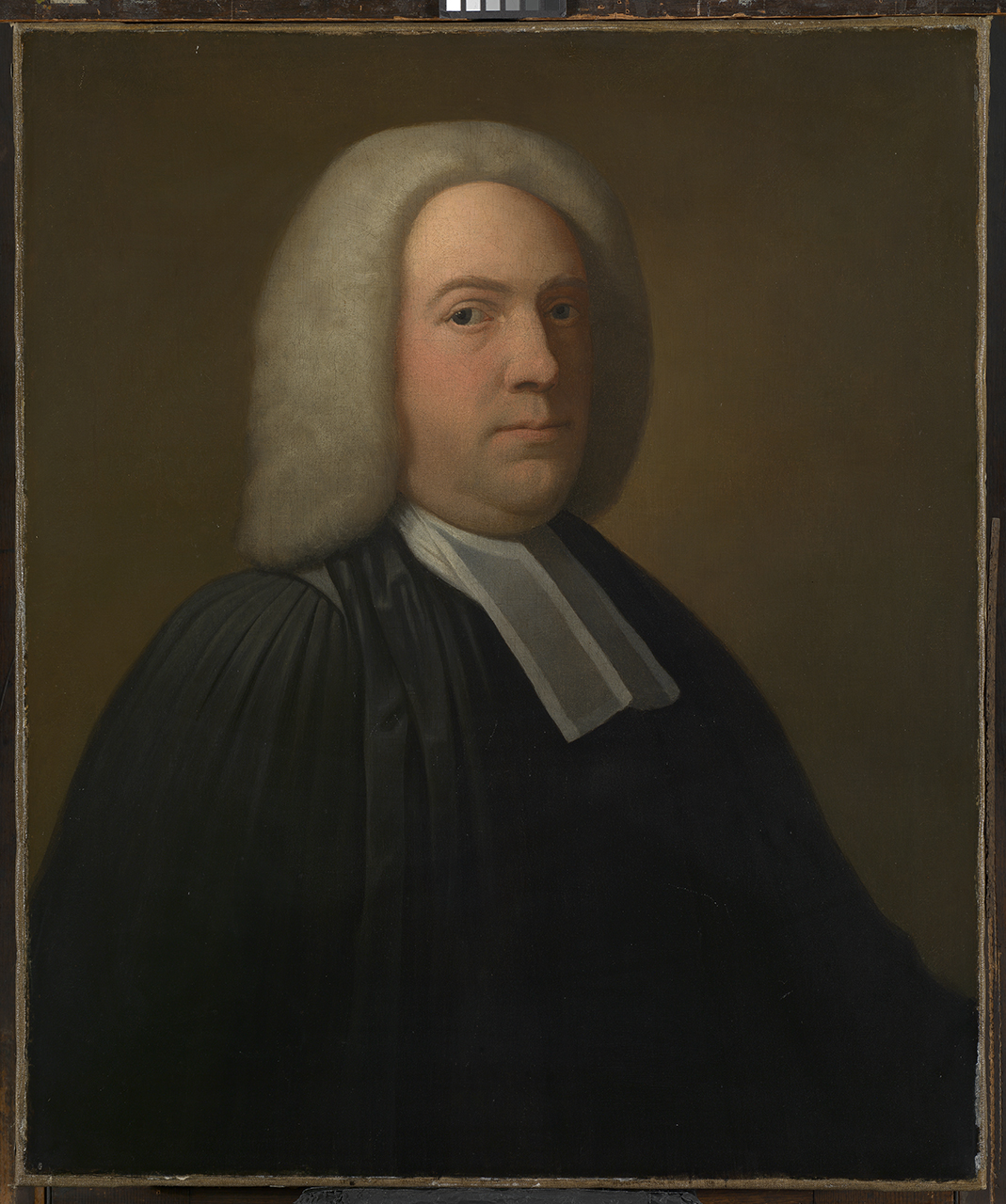

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

) - [JL]

47Takes me to task, come on Sir I'm prepar'd.

48Then by your favour, any thing that's

writ

49Against this gibeing jingling knack call'd Wit,

50Likes me abundantly, but you take care,

51Upon this point, not to be too severe.

52Perhaps my Muse, were fitter for

this part,

53For I profess, I can by very smart

54On Wit, which I abhor with all my

heart:

55I long

to lash it in some sharp Essay,libertinism

libertinismFor Margaret Ezell,

who writes about the performative quality of Restoration libertinism, Rochester's

libertinism was a deliberate assertion of privilege designed to cultivate power in

the court ("Enacting Libertinism: Court Performance and Literary Culture" in The Oxford English Literary History, Vol. V.). Rochester's

poem is a response to the question being asked here by a hypothetical clergyman

(the "formal band and beard"). Here, he is performing the persona of the pedantic,

prudish curate ultimately to mock him and his moral philosophy, thereby

cultivating a witty superiority.

56But your grand indiscretion bids me stay,

57And turns my Tide of Ink another way.

58What rage ferments in

your degen'rate mind,rage

59To make you rail at Reason, and Mankind?

rageThe

clergyman describes Rochester's mind as "degen[e]rate," and his way of thinking,

deviant. Rochester’s poem is a “Satire against Reason and Mankind”; it is

fundamentally skeptical of the ability--or desirability--of reason and law to

ameliorate baser human interests. - [TH]

60Bless glorious Man! to whom alone

kind Heav'n,

61An everlasting Soul has freely

giv'n;

62Whom his great Maker took such

care to make,

63That from himself he did the Image take;

64And this fair frame, in shining Reason drest,

65To dignifie his Nature, above

Beast.

66Reason, by whose aspiring influence,

67We take a flight beyond material sense.

68Dive into Mysteries, then soaring pierce,

69The flaming limits of the Universe.

70Search Heav'n and Hell, find out what's acted

there,

71And give the World true grounds of hope and

fear.

72Hold mighty Man, I

cryspeaker, all this we know,

speakerAt this point, Rochester's character speaks,

returning a satirical answer to the pedantic curate.

73From the Pathetique Pen of Ingello;Ignello

Ignello

Nathaniel

Ingelo, born ca 1621. Graduate and fellow of the Queen’s College,

Cambridge. Ingelo was a clergyman and author of a religious romance entitled Bentivolio and Urania. Marianne Thormählen writes in aRochester: The Poems in Context that the works of Ingelo and Simon

Patrick mentioned below would have been well known during Rochester’s time. She

mentions that Rochester would have detested “Ingelo’s exalted view of man; and his

attacks on Epicurus and his followers”.

9

74From P—

Pilgrimp,pSimon Patrick, Bishop of Ely (1626-1707) was an English

theologian and, eventually, bishop; his book The Parable of

the Pilgrim (1663/4) is referenced here. Patrick's Pilgrim is an allegory along the same lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Patrick’s first assignment after

graduating from Queen's College, Cambridge, was as a domestic chaplain to Sir

Walter St. John, John Wilmot’s uncle (Dictionary of National Biography)> - [TH]

S— replyss,

sRichard Sibbes

(1577-1635), was a popular Puritan theologian, minister, and writer, in the

affective tradition with intellectual connections to Calvinism. He is most well

known for a work called The Bruised Reed, but Rochester

here references a work this editor has not been able to trace. Other editions of

the poem replace "replies" with "soliloquies," possibly suggesting a different

work, Richard Bayne's Holy Soliloquies (1637)--Sibbes wa

very influenced by Bayne. Regardless, all of these references are to popular

theologians during the 17th century. . He, too, studied at Cambridge, but his

Puritanism caused him to lose a lectureship there (Dictionary of National Biography). - [TH]

75And 'tis this very reason I despise.

76This supernatural gift, that makes a Myte-,

77Think he is the Image of the Infinite:

78Comparing his short life, void of all rest,

79To the Eternal, and the ever blest.

80This busie, puzling, stirring up of doubt,

81That frames deep Mysteries, then finds 'em out;

82Filling with Frantick Crowds of thinking Fools,

83Those Reverend Bedlamsbedlam, Colledges, and Schools

bedlamBedlam is

the colloquial term for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, an asylum for the

mentally ill first established in 1676. It was often used as a broader term for

any location of perceived insanity. - [TH]

84Borne on whose Wings, each heavy Sotsot can pierce,

sotA sot is a stupid

person, usually someone who is "stupified" with liquor or habitually drunk

(OED). - [TH]

85The limits of the boundless Universe.

86Socomparison charming Oyntments,

make an Old Witch flie,

comparisonRochester compares the inflated ideology of the pedantic curate--whose "business"

is "Nonsense" and "impossibilities" (86)--with the superstitions that give witches

the power of flight. - [TH]

87And bear a Crippled Carcass through the Skie.

88'Tis this exalted pow'rpower, whose

bus'ness lies,

powerRochester

refers here to reason as the falsely "exalted pow'r." The remainder of the poem

will lay out why the poet thinks so. - [TH]

89In Nonsense, and impossibilities.

90This made a Whimsical Philosopher,

91Before the spacious World, his Tubtub prefer

tubThe word tub has a lot of meanings during this period. Proverbially,

it is used to refer to a fiction, or a made-up story; but it also specifically

refers to the pulpit from which a non-conformist preacher spoke. Nonconformity

refers to any religious faith not strictly Anglican. It also has another meaning

that

Rochester would have known about--a "sweating-tub" or a sort of barrel

encasing the

body used specifically to treat venereal disease. See the

OED. - [TH]

92And we have modern Cloysterd Coxcombs, who

93Retire to think, cause they have naught to do.

94But thoughts, are giv'n for Actions government,

95Where Action ceases, thoughts impertinent:

96Our Sphere of

Action, is lifes happiness,action

actionRochester became identified with philosophical and sexual libertinism of the

Restoration, which was characterized by the public, even performative pursuit of

pleasure and a vivid, almost nihilistic sexuality. Libertinism was underpinned by

a selective reading of Thomas Hobbes' theory of human nature. Hobbes, according to

Christopher Tilmouth, "declar[ed] that the passions, not reason, constituted the

proper, primary determinants of human conduct" and "posited...a new ideal of

happiness, equating felicity with a constant motion of the self from the

satisfaction of one appetite to the next, and he accorded fear and the lust for

power critical roles in this kinetic process" (Tilmouth 4-5).

Hobbes

characterized humankind in nature as in a permanent state of conflict and

struggle, governed by their appetites and their passions, and to avoid this

chaotic, violent state of nature, human societies contract with strong leaders to

bring order to passion and law to desire: "it is manifest that, during the time

men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that

condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every

man" (Leviathan, XIII, para. 8). Rochester positions his

libertinism as a moral freedom beyond the civil codes of contractual law. For more

on Restoration libertinism, see James Turner, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London, especially

chapter 6; and Diane Maybank'sarticle for the British Library about libertinism on the

Restoration stage. - [TH]

97And he who thinks Beyond, thinks like an Ass.

98Thus, whilst' gainst false reas'ning I inveigh,

99I own right Reason, which I wou'd obey:

100That Reason

that distinguishes by sensereasons,

reasonsRochester compares his materialist sense of reason--reason that rightly

"distinguishes by sense [perception]"--to the flawed or "false" reason of the

pedantic curate, that starts with the "beyond" (97). - [TH]

101And gives us Rules, of good, and ill from

thence:

102That bounds desires, with a reforming Will,

103To keep 'em more in vigour, not to kill.

104Your Reason hinders, mine helps t'enjoy,

105Renewing Apetites, yours wou'd destroy.

10

106My Reasons is my Friend, yours is a Cheat,

107Hungar call's out, my Reason bids me eat;

108Perversly yours, your Appetite does mock,

109This askt for Food, that answers what's a Clock?

110This plain distinction Sir your doubt secures,

111'Tis not true Reason I despise but yours.

112This I think Reason righted, but for Man,

113I'le nere recant defend him if you can.

114For all his Pride, and his Philosophy,

115'Tis evident, Beasts are in their degree,

116As wise at least, and better far than he.

117Those Creatures, are the wisest who attain,

118By surest means, the ends at which they aim.

119If therefore Jowlerjowler, finds, and Kills his Hares,

jowlerA common

name for a dog. - [TH]

120Better than M—m,

supplyes Committed Chairs;

mM-- is Henry

More, a rationalist Cartesian theologian who argues that God orders the world

infallibly and always according to the best ends ("the best of all possible

worlds"). He wrote several books, including On the Immortality

of the Soul, where he sought to counter the Hobbesian view of life outside

of society as "nasty, brutish, and short" and instead to prove "the exsitence of

immaterial substance, or spirit, and therefore God" (Stanford Encyclopedia

of Philosophy); he is most well known for his idea of the Spirit of

Nature, which connected the material world to the spiritual. Like other Platonists

of the 17th century, he believed that the immortality of the soul proved an

afterlife, characterized by damnation or salvation. Rochester disagreed with this

perspective. - [TH]

121Though one's a Sates-man, th'other but a Hound.

122Jowler, in Justice, wou'd be wiser found.

123You see how far Mans wisedom here extends,

134Look next, if humane Nature makes amends;

125Whose Principles, most gen'rous are, and just,

126And to whose Morals, you wou'd sooner trust.

127Be Judge your self, I'le bring it to the test,

128Which is the basest Creature Man, or Beast?beasts

beastsIn the

following lines, Rochester sets up an extended comparison between the nature of

violence in the animal kingdom and in the human world. - [TH]

129Birds feed on Birds, Beast

on each other prey,

130But Savage Man alone, does Man betray:

131Prest by necessity, they Kill for Food,

132Man, undoes Man, to do

himself no good.

133With Teeth, & Claws: by Nature arm'd thy hunt,

134Natures allowance, to supply their want.

135But Man, with smiles, embraces Friendships,

praise.

136Unhumanely his Fellows life betrays;

11

137With voluntary pains, works his distress,

138Not through necessity, but wantonness.

139For hunger, or for Love, they fight, or tear,

140Whilst wretched Man, is still in Arms for fear;

141For fear he Armes, and is of Armes afraid,

142By fear, to fear, successively betray'd

143Base fear, the fource whence his best passion came,

144His boasted Honour, and his dear bought Fame.

145That lust of Pow'r, to which he's such a Slave,

146And for the which alone he dares be brave:

147To which his various Projects are design'd,

148Which makes him gen'rous, affable, and kind.

149For which he takes such pains to be thought wise,

150And screws his actions, in a forc'd disguise:

151Leading a tedious life in Misery,

152Under laborious, mean Hypocrisie.

153Look to the bottom, of his vast design,

154Wherein Mans Wisdom, Pow'r, and Glory joyn;

155The good he acts, the ill he does endure;

156'Tis all for fear, to make himself secure.

157Meerly for safety, after Fame we thirst,

158For all Men, wou'd be Cowards if they durst.

159And honesty's against all common sense,

160Men must be Knaves, 'tis in

their own defence.

161Mankind's dishonest, if you think it fair;

162Amongst known Cheats,

to play upon the squaresquare,

square"To play

upon the square" means to play fairly (or "fair and square," in current colloquial

terms). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this expression was "[v]ery

common from c1670, frequently with reference to...gaming" ("square," adj.,

III.12.b). - [TH]

163You'le be undone -----

-------dashes

dashesDuring this period, dashes were often used to

visibly omit a name that would identify the subject of satire. Usually,

contemporary readers would have understood who the author was referring to.

164Nor can weak truth, your reputation save,

165The Knaves, will all agree to call you Knave.

166VVrong'd shall he live, insulted o're, opprest.

167VVho dares be less a Villain, than the rest.

12

168Thus Sir you see what humane Nature

cravesnature,

natureIn Leviathan (1651), Hobbes argued that humans are completely

driven by the primary drives of appetite and aversion; people are selfish at their

root. In the state of nature, which is a state of war, “there is no place for

industry...; no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is

worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man

solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Paragraph 9, Chapter 13, Leviathan). - [TH]

169Most Men are Cowards, all Men shou'd be Knaves:

170The diff'rence lyes (as far as I can see)

171Not in the thing it self, but the degree;

172And all the subject matter of debate,

173Is only who's a Knave, of the first Rate?

174All this with indignation have I hurl'd,

175At the pretending part of the proud World,

176Who swolne with selfish vanity, devise,

177False freedoms, holy Cheats, and formal Lyes

178Over their fellow Slaves,slaves to tyrannize.

slavesRochester suggests that "the pretending part of the proud World" (175) use their

supposed spiritual superiority to weild tyrranical power over other people, not

recognizing that everyone is a "Slave." - [TH]

179But if in Courtcourt, so just a Man there be,

courtCourt

here, as elsewhere, refers to the court of nobles and other people of power

surrounding King Charles II (or whomever was monarch at the time). Court culture,

in the Restoration, was often characterized both by stringent absolutism and a

permissiveness that distinguished those of privilege. To read more about

Restoration court culture, see Culture and Politics at the Court of Charles II,

1660-1685, by Matthew Jenkinson. - [TH]

180(In Court, a just Man, yet unknown to me.)

181Who does his needful flattery direct,

182Not to oppress, and ruine, but protect;

183Since flattery which may so ever laid,

184Is still a Tax on that unhappy Trade.

185If so upright a States-Man, you can find,

186Whose passions bend to his unbyas'd Mind;

187Who does his Arts, and Policies apply,

188To raise his Country, not his Family;

189Nor while his Pride, own'd Avarice withstands,

190Receives Aurealaureal Bribes, from

Friends corrupted hands.

aurealReaders may

be more familiar with the noun form ("aura") of this obsolete adjective. "Aureal

Bribes" are bribes that are gilded or golden (OED). - [TH]

191Is there a Church-Man who on God relyes?

192Whose Life, his Faith, and Doctrine Justifies?

193Not one blown up, with vain Prelatique Pride,

194Who for reproof of Sins, does Man deride:

195Whose envious heart with his obstrep'ous sawcy Eloquence,

196Dares chide at Kings, and raile at Men of

sense.

13

197Who from his Pulpit, vents more peevish lies,

198More bitter railings, scandals, Calumnies,

199Than at a Gossipping, are thrown about,

200When the good Wives get drunk, and then fall

out.

201None of that sensual Tribe, whose Talents lye,

202In Avarice, Pride, Sloth, and Gluttony.

203Who hunt good Livings, but abhor good Lives,

204Whose lust exalted, to that height arrives,

205They act Adūltery with their own Wives.

206And e're a score of years compleated be,

207Can from the lofty Pulpit proudly see,

208Half a large Parish, their own Progeny.

209Nor doating B—b who wou'd be ador'd,

bOther versions of Rochester's poem

replace the initial with "bishops."

210For domineering at the Councel Board;

211A greater Fop, in business at fourscorefourscore,

fourscoreA unit

of measurement, usually of time. A "score" is twenty; so, four score is four times

twenty, or eighty. - [TH]

212Fonder of serious Toyes, affected more,

213Than the gay glitt'ring Fool, at twenty proves,

214With all his noise, his tawdrey Cloaths, and loves,

215But a meek humble Man, of modest sense,

216Who Preaching peace, does practice continence;

217Whose pious life's a proof he does believe,

218Misterious truths, which no Man can conceive.

219Ifif upon Earth

there dwell such God like Men,

ifRochester here

makes an IF/THEN logical statement. If such "[in]conceiv[ably]" (218) "meek humble

M[e]n, of modest sense" (215) can be revealed, he'll "recant" (220) this poetic

statement. - [TH]

220I'le here recant my Paradox to them.

221Adore those Shrines of Vertue,

Homage pay,

222And with the Rabble Worldrabble, their Laws obey.

rabble"Rabble" here is used as a

derogatory term to refer to the masses or the common people--and "their Laws"

(222)--from which mob Rochester distances himself through his libertinism. See the

OED "rabble," n.1 and adj., particularly sense 3.

223If such there are, yet grant me this at least,

224Man differs more from Man,

than Man from Beast.

ON SEVERAL

OCCASIONS

Printed at ANTWERP,Antwerp Antwerp 'Antwerp’ is a false imprint. James Thorpe discusses this interesting detail in The Earliest Editions of Rochester’s Poems" noting that the printings were “unlicensed books printed in London” where the false imprint was used for “simple subterfuge presumably intended to attract the lovers of racy literature or distract prosecution”. - [JL] 1690.

6 SATYR [AGAINST REASON AND MANKIND]

1WEre I (who to my cost already am 2One of those strange prodigious Creatures Man.) 3A Spirit free, to choose for my own share, 4What case of Flesh, and Blood, I pleas'd to wear, 5I'd be a Dog, a Monkey, or a Bear. 6Or any thing but that vain Animal, 7Who is so proud of being rational. 8The senses are too grossgross, and he'll contrive grossIn this sense, gross refers to materiality as distinct from ethereality or spirituality. See OED adj III.8.c: describes "things material or perceptible to the senses, as contrasted with what is spiritual, ethereal, or impalpable." - [MUStudStaff] 9A Sixth, to contradict the other Five; 10And before certain instinct, will preferr 11Reason, which Fifty times for one does err. 7 12Reason, an Ignis fatuus,ignus-fatuusignus-fatuusFrom the Latin meaning, literally, "foolish fire," an ignis fatuus is a will-o'the-wisp, a flitting phosphorescent light that led travelers astray in marshy areas like the "Fenny Bogs and Thorny Brakes" (15) Rochester describes below (OED, "ignis fatuus, n."). - [JL] in the Mind, 13Which leaving light of Nature, sense behind; 14Pathless and dan'grous wandring ways it takes, 15Through errors, Fenny-Boggs, and Thorny Brakes; 16Whilst the misguided follower, climbs with pain, 17Mountains of Whimseys, heap'd in his own Brain: 18Stumbling from thought to thought, falls headlong down, 19Into doubts boundless Sea, where like to drown. 20Books bear him up awhile, and makes him try, 21To swim with Bladders of Philosophy; 22In hopes still t'oretake th'escaping light, 23The Vapour dances in his dazling sight, 24Till spent, it leaves him to eternal Night. 25Then Old Age, and experience, hand in hand, 26Lead him to death, and make him understand, 27After a search so painful, and so long, 28That all his Life he has been in the wrongwrong; wrongLines 29-36 explain how, from Rochester's perspective, this approach to life that prizes reason is "in the wrong." - [TH] 29Hudled in dirt, the reas'ning Engine lyes,reason reasonThe "reasoning Enging" is the mind--here, Rochester notes that the mind is "huddled in [the] dirt" of the physical body. The body and the mind are intertwined, rather than separate. - [TH] 30Who was so proud, so witty, and so wise, 31Pride drew him in, as Cheats, their Bubblesbubbles, catch, bubblesHere used as a noun, "bubbles" in this sense refers to those who have been fooled or cheated (OED, n.2b). - [TH] 32And makes him venture, to be made a Wretch. 33His wisdom did his happiness destroy, 34Aiming to know what World he shou'd enjoy; 35And Wit, was his vain frivolous pretence, 36Of pleasing others, at his own expence. 37For Wittswitswits During the Restoration period in England, Charles II would often be found in the company of young intellectuals or "wits." In The Court Wits of the Restoration, John Harold Wilson writes that “the label Wit was attached only to one who made some real pretense to distinction as a poet, critic, translator, raconteur, or a man of learning" (6). Among the so-called "court wits" were Rochester, Sir John Suckling, Edmund Waller, and others. [add paraphrase from page 5 of Tilmouth: https://books.google.com/books?id=DipmhwkFfQMC - [JL] are treated just like common Whores, 38First they're enjoy'd, and then kickt out of Doores, 39The pleasurepleasure past, a threatning doubt remains, pleasureAs Jeremy Webster argues in Performing Libertinism in Charles II’s Court, “[l]ibertines...performed traditionally secretive acts— excessive drinking, carnality, sodomy, sedition, assault, and sacrilege—in the public sphere in a variety of ways” (2). Here, Rochester is talking in part about sexual pleasure that, once enjoyed, brings causes the enjoyer to fear or hate that pleasure. This fear is in part existential or philosophical--pleasure brings with it "dang'rous" (41) questions about the value of social order founded on reason--but it is also material, as in the fear of sexually transmitted infection, from which Rochester sufferred. The "succeeding pains" (40) to which he refers encapsulate both kinds of fears. - [TH] 40That frights th'enjoyer, with succeeding pains: 41Women and Men of Wit, are dang'rous Tools, 42And ever fatal to admiring Fools. 8 43Pleasure allures, and when the FoppsfopsfopsIn "Fops and Some Versions of Foppery," Robert B. Heilman discusses this term, noting that as a “general, all-purpose carrier of disapproval, fop works much like fool" (364). - [JL] escape, 44'Tis not that they're belov'd, but fortunate, 45And therefore what thy fear, at least they hate. 46But now methinks some formal Band, and Beard,bandband

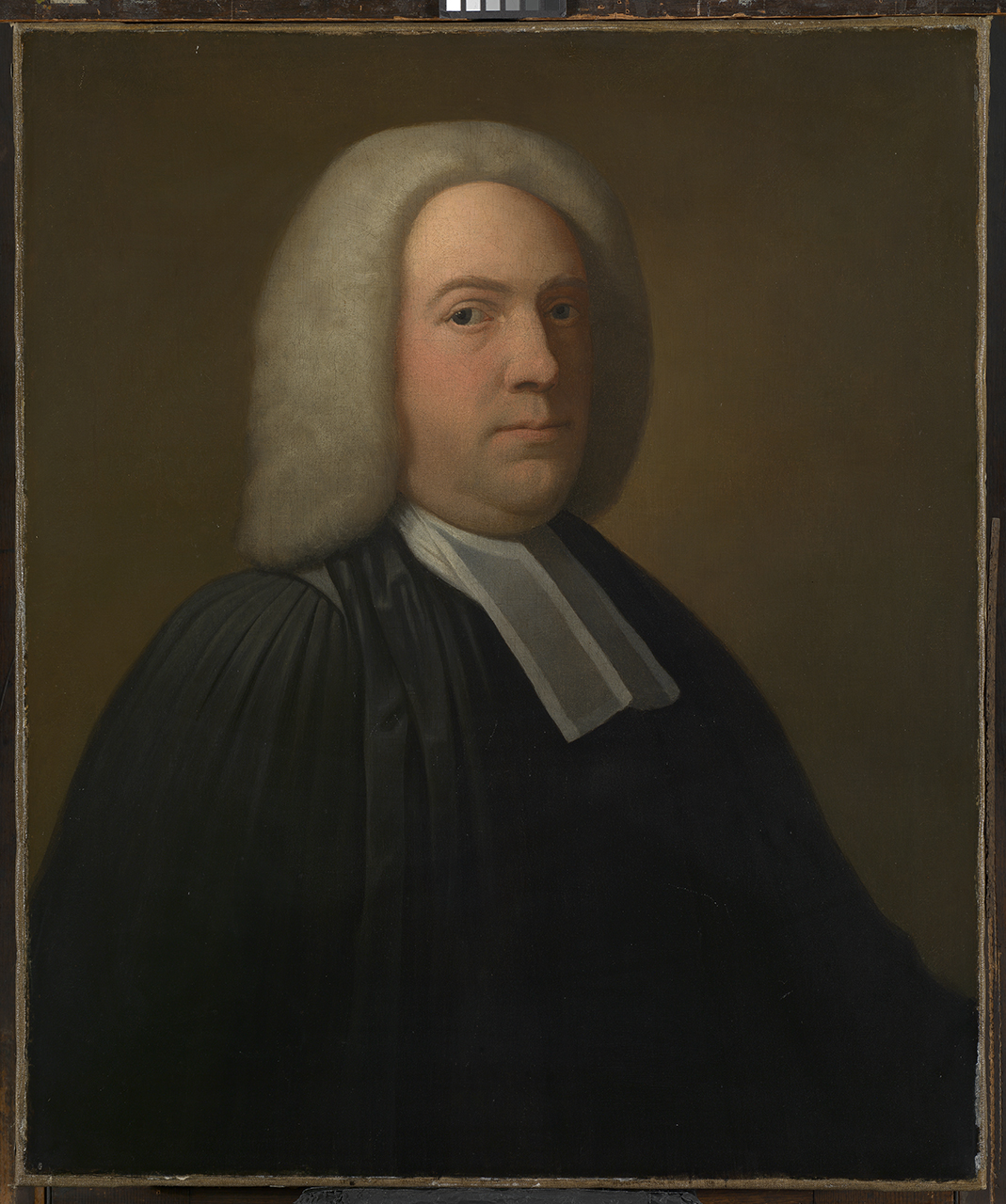

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

) - [JL]

47Takes me to task, come on Sir I'm prepar'd.

48Then by your favour, any thing that's

writ

49Against this gibeing jingling knack call'd Wit,

50Likes me abundantly, but you take care,

51Upon this point, not to be too severe.

52Perhaps my Muse, were fitter for

this part,

53For I profess, I can by very smart

54On Wit, which I abhor with all my

heart:

55I long

to lash it in some sharp Essay,libertinism

libertinismFor Margaret Ezell,

who writes about the performative quality of Restoration libertinism, Rochester's

libertinism was a deliberate assertion of privilege designed to cultivate power in

the court ("Enacting Libertinism: Court Performance and Literary Culture" in The Oxford English Literary History, Vol. V.). Rochester's

poem is a response to the question being asked here by a hypothetical clergyman

(the "formal band and beard"). Here, he is performing the persona of the pedantic,

prudish curate ultimately to mock him and his moral philosophy, thereby

cultivating a witty superiority.

56But your grand indiscretion bids me stay,

57And turns my Tide of Ink another way.

58What rage ferments in

your degen'rate mind,rage

59To make you rail at Reason, and Mankind?

rageThe

clergyman describes Rochester's mind as "degen[e]rate," and his way of thinking,

deviant. Rochester’s poem is a “Satire against Reason and Mankind”; it is

fundamentally skeptical of the ability--or desirability--of reason and law to

ameliorate baser human interests. - [TH]

60Bless glorious Man! to whom alone

kind Heav'n,

61An everlasting Soul has freely

giv'n;

62Whom his great Maker took such

care to make,

63That from himself he did the Image take;

64And this fair frame, in shining Reason drest,

65To dignifie his Nature, above

Beast.

66Reason, by whose aspiring influence,

67We take a flight beyond material sense.

68Dive into Mysteries, then soaring pierce,

69The flaming limits of the Universe.

70Search Heav'n and Hell, find out what's acted

there,

71And give the World true grounds of hope and

fear.

72Hold mighty Man, I

cryspeaker, all this we know,

speakerAt this point, Rochester's character speaks,

returning a satirical answer to the pedantic curate.

73From the Pathetique Pen of Ingello;Ignello

Ignello

Nathaniel

Ingelo, born ca 1621. Graduate and fellow of the Queen’s College,

Cambridge. Ingelo was a clergyman and author of a religious romance entitled Bentivolio and Urania. Marianne Thormählen writes in aRochester: The Poems in Context that the works of Ingelo and Simon

Patrick mentioned below would have been well known during Rochester’s time. She

mentions that Rochester would have detested “Ingelo’s exalted view of man; and his

attacks on Epicurus and his followers”.

9

74From P—

Pilgrimp,pSimon Patrick, Bishop of Ely (1626-1707) was an English

theologian and, eventually, bishop; his book The Parable of

the Pilgrim (1663/4) is referenced here. Patrick's Pilgrim is an allegory along the same lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Patrick’s first assignment after

graduating from Queen's College, Cambridge, was as a domestic chaplain to Sir

Walter St. John, John Wilmot’s uncle (Dictionary of National Biography)> - [TH]

S— replyss,

sRichard Sibbes

(1577-1635), was a popular Puritan theologian, minister, and writer, in the

affective tradition with intellectual connections to Calvinism. He is most well

known for a work called The Bruised Reed, but Rochester

here references a work this editor has not been able to trace. Other editions of

the poem replace "replies" with "soliloquies," possibly suggesting a different

work, Richard Bayne's Holy Soliloquies (1637)--Sibbes wa

very influenced by Bayne. Regardless, all of these references are to popular

theologians during the 17th century. . He, too, studied at Cambridge, but his

Puritanism caused him to lose a lectureship there (Dictionary of National Biography). - [TH]

75And 'tis this very reason I despise.

76This supernatural gift, that makes a Myte-,

77Think he is the Image of the Infinite:

78Comparing his short life, void of all rest,

79To the Eternal, and the ever blest.

80This busie, puzling, stirring up of doubt,

81That frames deep Mysteries, then finds 'em out;

82Filling with Frantick Crowds of thinking Fools,

83Those Reverend Bedlamsbedlam, Colledges, and Schools

bedlamBedlam is

the colloquial term for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, an asylum for the

mentally ill first established in 1676. It was often used as a broader term for

any location of perceived insanity. - [TH]

84Borne on whose Wings, each heavy Sotsot can pierce,

sotA sot is a stupid

person, usually someone who is "stupified" with liquor or habitually drunk

(OED). - [TH]

85The limits of the boundless Universe.

86Socomparison charming Oyntments,

make an Old Witch flie,

comparisonRochester compares the inflated ideology of the pedantic curate--whose "business"

is "Nonsense" and "impossibilities" (86)--with the superstitions that give witches

the power of flight. - [TH]

87And bear a Crippled Carcass through the Skie.

88'Tis this exalted pow'rpower, whose

bus'ness lies,

powerRochester

refers here to reason as the falsely "exalted pow'r." The remainder of the poem

will lay out why the poet thinks so. - [TH]

89In Nonsense, and impossibilities.

90This made a Whimsical Philosopher,

91Before the spacious World, his Tubtub prefer

tubThe word tub has a lot of meanings during this period. Proverbially,

it is used to refer to a fiction, or a made-up story; but it also specifically

refers to the pulpit from which a non-conformist preacher spoke. Nonconformity

refers to any religious faith not strictly Anglican. It also has another meaning

that

Rochester would have known about--a "sweating-tub" or a sort of barrel

encasing the

body used specifically to treat venereal disease. See the

OED. - [TH]

92And we have modern Cloysterd Coxcombs, who

93Retire to think, cause they have naught to do.

94But thoughts, are giv'n for Actions government,

95Where Action ceases, thoughts impertinent:

96Our Sphere of

Action, is lifes happiness,action

actionRochester became identified with philosophical and sexual libertinism of the

Restoration, which was characterized by the public, even performative pursuit of

pleasure and a vivid, almost nihilistic sexuality. Libertinism was underpinned by

a selective reading of Thomas Hobbes' theory of human nature. Hobbes, according to

Christopher Tilmouth, "declar[ed] that the passions, not reason, constituted the

proper, primary determinants of human conduct" and "posited...a new ideal of

happiness, equating felicity with a constant motion of the self from the

satisfaction of one appetite to the next, and he accorded fear and the lust for

power critical roles in this kinetic process" (Tilmouth 4-5).

Hobbes

characterized humankind in nature as in a permanent state of conflict and

struggle, governed by their appetites and their passions, and to avoid this

chaotic, violent state of nature, human societies contract with strong leaders to

bring order to passion and law to desire: "it is manifest that, during the time

men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that

condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every

man" (Leviathan, XIII, para. 8). Rochester positions his

libertinism as a moral freedom beyond the civil codes of contractual law. For more

on Restoration libertinism, see James Turner, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London, especially

chapter 6; and Diane Maybank'sarticle for the British Library about libertinism on the

Restoration stage. - [TH]

97And he who thinks Beyond, thinks like an Ass.

98Thus, whilst' gainst false reas'ning I inveigh,

99I own right Reason, which I wou'd obey:

100That Reason

that distinguishes by sensereasons,

reasonsRochester compares his materialist sense of reason--reason that rightly

"distinguishes by sense [perception]"--to the flawed or "false" reason of the

pedantic curate, that starts with the "beyond" (97). - [TH]

101And gives us Rules, of good, and ill from

thence:

102That bounds desires, with a reforming Will,

103To keep 'em more in vigour, not to kill.

104Your Reason hinders, mine helps t'enjoy,

105Renewing Apetites, yours wou'd destroy.

10

106My Reasons is my Friend, yours is a Cheat,

107Hungar call's out, my Reason bids me eat;

108Perversly yours, your Appetite does mock,

109This askt for Food, that answers what's a Clock?

110This plain distinction Sir your doubt secures,

111'Tis not true Reason I despise but yours.

112This I think Reason righted, but for Man,

113I'le nere recant defend him if you can.

114For all his Pride, and his Philosophy,

115'Tis evident, Beasts are in their degree,

116As wise at least, and better far than he.

117Those Creatures, are the wisest who attain,

118By surest means, the ends at which they aim.

119If therefore Jowlerjowler, finds, and Kills his Hares,

jowlerA common

name for a dog. - [TH]

120Better than M—m,

supplyes Committed Chairs;

mM-- is Henry

More, a rationalist Cartesian theologian who argues that God orders the world

infallibly and always according to the best ends ("the best of all possible

worlds"). He wrote several books, including On the Immortality

of the Soul, where he sought to counter the Hobbesian view of life outside

of society as "nasty, brutish, and short" and instead to prove "the exsitence of

immaterial substance, or spirit, and therefore God" (Stanford Encyclopedia

of Philosophy); he is most well known for his idea of the Spirit of

Nature, which connected the material world to the spiritual. Like other Platonists

of the 17th century, he believed that the immortality of the soul proved an

afterlife, characterized by damnation or salvation. Rochester disagreed with this

perspective. - [TH]

121Though one's a Sates-man, th'other but a Hound.

122Jowler, in Justice, wou'd be wiser found.

123You see how far Mans wisedom here extends,

134Look next, if humane Nature makes amends;

125Whose Principles, most gen'rous are, and just,

126And to whose Morals, you wou'd sooner trust.

127Be Judge your self, I'le bring it to the test,

128Which is the basest Creature Man, or Beast?beasts

beastsIn the

following lines, Rochester sets up an extended comparison between the nature of

violence in the animal kingdom and in the human world. - [TH]

129Birds feed on Birds, Beast

on each other prey,

130But Savage Man alone, does Man betray:

131Prest by necessity, they Kill for Food,

132Man, undoes Man, to do

himself no good.

133With Teeth, & Claws: by Nature arm'd thy hunt,

134Natures allowance, to supply their want.

135But Man, with smiles, embraces Friendships,

praise.

136Unhumanely his Fellows life betrays;

11

137With voluntary pains, works his distress,

138Not through necessity, but wantonness.

139For hunger, or for Love, they fight, or tear,

140Whilst wretched Man, is still in Arms for fear;

141For fear he Armes, and is of Armes afraid,

142By fear, to fear, successively betray'd

143Base fear, the fource whence his best passion came,

144His boasted Honour, and his dear bought Fame.

145That lust of Pow'r, to which he's such a Slave,

146And for the which alone he dares be brave:

147To which his various Projects are design'd,

148Which makes him gen'rous, affable, and kind.

149For which he takes such pains to be thought wise,

150And screws his actions, in a forc'd disguise:

151Leading a tedious life in Misery,

152Under laborious, mean Hypocrisie.

153Look to the bottom, of his vast design,

154Wherein Mans Wisdom, Pow'r, and Glory joyn;

155The good he acts, the ill he does endure;

156'Tis all for fear, to make himself secure.

157Meerly for safety, after Fame we thirst,

158For all Men, wou'd be Cowards if they durst.

159And honesty's against all common sense,

160Men must be Knaves, 'tis in

their own defence.

161Mankind's dishonest, if you think it fair;

162Amongst known Cheats,

to play upon the squaresquare,

square"To play

upon the square" means to play fairly (or "fair and square," in current colloquial

terms). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this expression was "[v]ery

common from c1670, frequently with reference to...gaming" ("square," adj.,

III.12.b). - [TH]

163You'le be undone -----

-------dashes

dashesDuring this period, dashes were often used to

visibly omit a name that would identify the subject of satire. Usually,

contemporary readers would have understood who the author was referring to.

164Nor can weak truth, your reputation save,

165The Knaves, will all agree to call you Knave.

166VVrong'd shall he live, insulted o're, opprest.

167VVho dares be less a Villain, than the rest.

12

168Thus Sir you see what humane Nature

cravesnature,

natureIn Leviathan (1651), Hobbes argued that humans are completely

driven by the primary drives of appetite and aversion; people are selfish at their

root. In the state of nature, which is a state of war, “there is no place for

industry...; no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is

worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man

solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Paragraph 9, Chapter 13, Leviathan). - [TH]

169Most Men are Cowards, all Men shou'd be Knaves:

170The diff'rence lyes (as far as I can see)

171Not in the thing it self, but the degree;

172And all the subject matter of debate,

173Is only who's a Knave, of the first Rate?

174All this with indignation have I hurl'd,

175At the pretending part of the proud World,

176Who swolne with selfish vanity, devise,

177False freedoms, holy Cheats, and formal Lyes

178Over their fellow Slaves,slaves to tyrannize.

slavesRochester suggests that "the pretending part of the proud World" (175) use their

supposed spiritual superiority to weild tyrranical power over other people, not

recognizing that everyone is a "Slave." - [TH]

179But if in Courtcourt, so just a Man there be,

courtCourt

here, as elsewhere, refers to the court of nobles and other people of power

surrounding King Charles II (or whomever was monarch at the time). Court culture,

in the Restoration, was often characterized both by stringent absolutism and a

permissiveness that distinguished those of privilege. To read more about

Restoration court culture, see Culture and Politics at the Court of Charles II,

1660-1685, by Matthew Jenkinson. - [TH]

180(In Court, a just Man, yet unknown to me.)

181Who does his needful flattery direct,

182Not to oppress, and ruine, but protect;

183Since flattery which may so ever laid,

184Is still a Tax on that unhappy Trade.

185If so upright a States-Man, you can find,

186Whose passions bend to his unbyas'd Mind;

187Who does his Arts, and Policies apply,

188To raise his Country, not his Family;

189Nor while his Pride, own'd Avarice withstands,

190Receives Aurealaureal Bribes, from

Friends corrupted hands.

aurealReaders may

be more familiar with the noun form ("aura") of this obsolete adjective. "Aureal

Bribes" are bribes that are gilded or golden (OED). - [TH]

191Is there a Church-Man who on God relyes?

192Whose Life, his Faith, and Doctrine Justifies?

193Not one blown up, with vain Prelatique Pride,

194Who for reproof of Sins, does Man deride:

195Whose envious heart with his obstrep'ous sawcy Eloquence,

196Dares chide at Kings, and raile at Men of

sense.

13

197Who from his Pulpit, vents more peevish lies,

198More bitter railings, scandals, Calumnies,

199Than at a Gossipping, are thrown about,

200When the good Wives get drunk, and then fall

out.

201None of that sensual Tribe, whose Talents lye,

202In Avarice, Pride, Sloth, and Gluttony.

203Who hunt good Livings, but abhor good Lives,

204Whose lust exalted, to that height arrives,

205They act Adūltery with their own Wives.

206And e're a score of years compleated be,

207Can from the lofty Pulpit proudly see,

208Half a large Parish, their own Progeny.

209Nor doating B—b who wou'd be ador'd,

bOther versions of Rochester's poem

replace the initial with "bishops."

210For domineering at the Councel Board;

211A greater Fop, in business at fourscorefourscore,

fourscoreA unit

of measurement, usually of time. A "score" is twenty; so, four score is four times

twenty, or eighty. - [TH]

212Fonder of serious Toyes, affected more,

213Than the gay glitt'ring Fool, at twenty proves,

214With all his noise, his tawdrey Cloaths, and loves,

215But a meek humble Man, of modest sense,

216Who Preaching peace, does practice continence;

217Whose pious life's a proof he does believe,

218Misterious truths, which no Man can conceive.

219Ifif upon Earth

there dwell such God like Men,

ifRochester here

makes an IF/THEN logical statement. If such "[in]conceiv[ably]" (218) "meek humble

M[e]n, of modest sense" (215) can be revealed, he'll "recant" (220) this poetic

statement. - [TH]

220I'le here recant my Paradox to them.

221Adore those Shrines of Vertue,

Homage pay,

222And with the Rabble Worldrabble, their Laws obey.

rabble"Rabble" here is used as a

derogatory term to refer to the masses or the common people--and "their Laws"

(222)--from which mob Rochester distances himself through his libertinism. See the

OED "rabble," n.1 and adj., particularly sense 3.

223If such there are, yet grant me this at least,

224Man differs more from Man,

than Man from Beast.

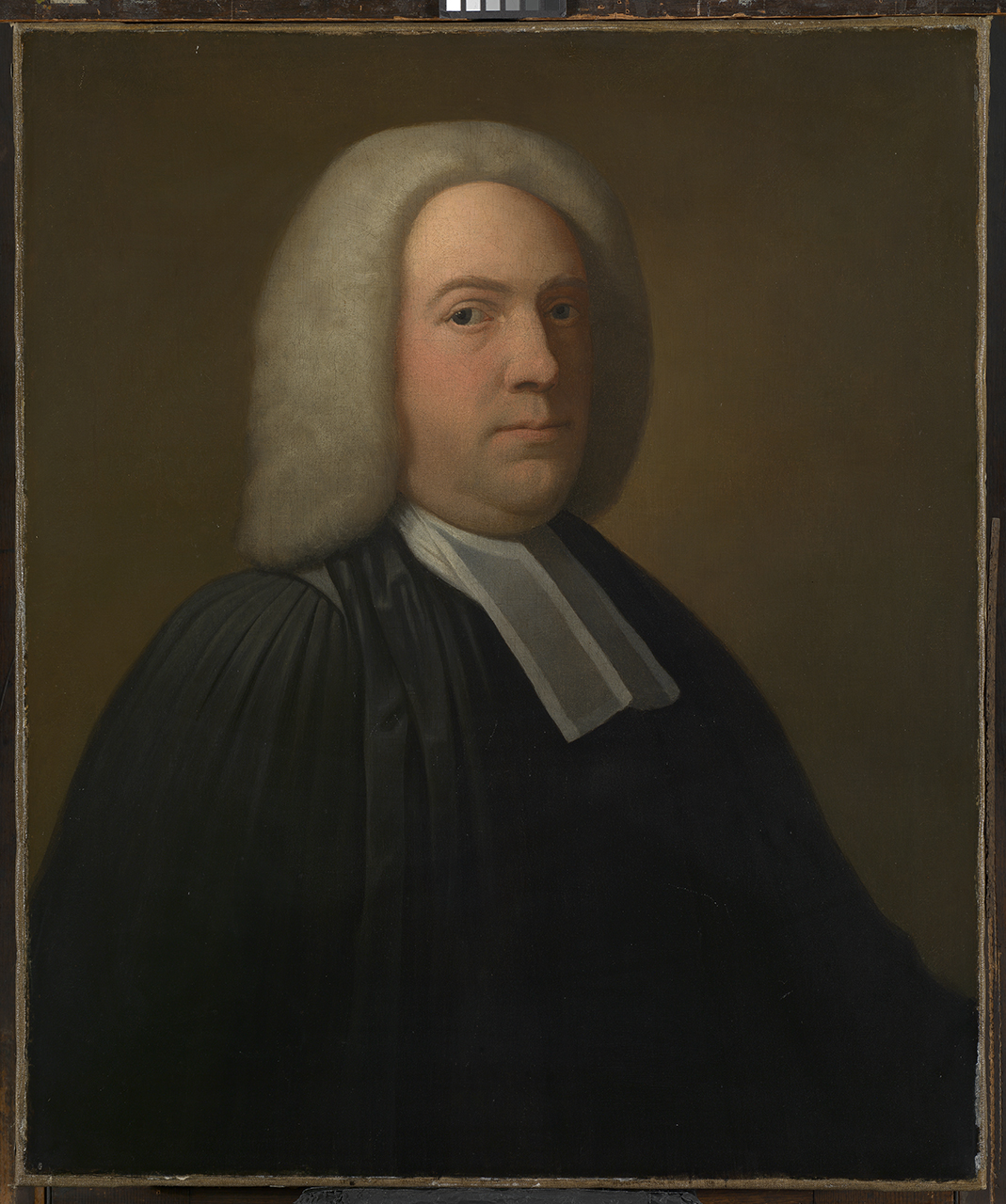

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

) - [JL]

47Takes me to task, come on Sir I'm prepar'd.

48Then by your favour, any thing that's

writ

49Against this gibeing jingling knack call'd Wit,

50Likes me abundantly, but you take care,

51Upon this point, not to be too severe.

52Perhaps my Muse, were fitter for

this part,

53For I profess, I can by very smart

54On Wit, which I abhor with all my

heart:

55I long

to lash it in some sharp Essay,libertinism

libertinismFor Margaret Ezell,

who writes about the performative quality of Restoration libertinism, Rochester's

libertinism was a deliberate assertion of privilege designed to cultivate power in

the court ("Enacting Libertinism: Court Performance and Literary Culture" in The Oxford English Literary History, Vol. V.). Rochester's

poem is a response to the question being asked here by a hypothetical clergyman

(the "formal band and beard"). Here, he is performing the persona of the pedantic,

prudish curate ultimately to mock him and his moral philosophy, thereby

cultivating a witty superiority.

56But your grand indiscretion bids me stay,

57And turns my Tide of Ink another way.

58What rage ferments in

your degen'rate mind,rage

59To make you rail at Reason, and Mankind?

rageThe

clergyman describes Rochester's mind as "degen[e]rate," and his way of thinking,

deviant. Rochester’s poem is a “Satire against Reason and Mankind”; it is

fundamentally skeptical of the ability--or desirability--of reason and law to

ameliorate baser human interests. - [TH]

60Bless glorious Man! to whom alone

kind Heav'n,

61An everlasting Soul has freely

giv'n;

62Whom his great Maker took such

care to make,

63That from himself he did the Image take;

64And this fair frame, in shining Reason drest,

65To dignifie his Nature, above

Beast.

66Reason, by whose aspiring influence,

67We take a flight beyond material sense.

68Dive into Mysteries, then soaring pierce,

69The flaming limits of the Universe.

70Search Heav'n and Hell, find out what's acted

there,

71And give the World true grounds of hope and

fear.

72Hold mighty Man, I

cryspeaker, all this we know,

speakerAt this point, Rochester's character speaks,

returning a satirical answer to the pedantic curate.

73From the Pathetique Pen of Ingello;Ignello

Ignello

Nathaniel

Ingelo, born ca 1621. Graduate and fellow of the Queen’s College,

Cambridge. Ingelo was a clergyman and author of a religious romance entitled Bentivolio and Urania. Marianne Thormählen writes in aRochester: The Poems in Context that the works of Ingelo and Simon

Patrick mentioned below would have been well known during Rochester’s time. She

mentions that Rochester would have detested “Ingelo’s exalted view of man; and his

attacks on Epicurus and his followers”.

9

74From P—

Pilgrimp,pSimon Patrick, Bishop of Ely (1626-1707) was an English

theologian and, eventually, bishop; his book The Parable of

the Pilgrim (1663/4) is referenced here. Patrick's Pilgrim is an allegory along the same lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Patrick’s first assignment after

graduating from Queen's College, Cambridge, was as a domestic chaplain to Sir

Walter St. John, John Wilmot’s uncle (Dictionary of National Biography)> - [TH]

S— replyss,

sRichard Sibbes

(1577-1635), was a popular Puritan theologian, minister, and writer, in the

affective tradition with intellectual connections to Calvinism. He is most well

known for a work called The Bruised Reed, but Rochester

here references a work this editor has not been able to trace. Other editions of

the poem replace "replies" with "soliloquies," possibly suggesting a different

work, Richard Bayne's Holy Soliloquies (1637)--Sibbes wa

very influenced by Bayne. Regardless, all of these references are to popular

theologians during the 17th century. . He, too, studied at Cambridge, but his

Puritanism caused him to lose a lectureship there (Dictionary of National Biography). - [TH]

75And 'tis this very reason I despise.

76This supernatural gift, that makes a Myte-,

77Think he is the Image of the Infinite:

78Comparing his short life, void of all rest,

79To the Eternal, and the ever blest.

80This busie, puzling, stirring up of doubt,

81That frames deep Mysteries, then finds 'em out;

82Filling with Frantick Crowds of thinking Fools,

83Those Reverend Bedlamsbedlam, Colledges, and Schools

bedlamBedlam is

the colloquial term for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, an asylum for the

mentally ill first established in 1676. It was often used as a broader term for

any location of perceived insanity. - [TH]

84Borne on whose Wings, each heavy Sotsot can pierce,

sotA sot is a stupid

person, usually someone who is "stupified" with liquor or habitually drunk

(OED). - [TH]

85The limits of the boundless Universe.

86Socomparison charming Oyntments,

make an Old Witch flie,

comparisonRochester compares the inflated ideology of the pedantic curate--whose "business"

is "Nonsense" and "impossibilities" (86)--with the superstitions that give witches

the power of flight. - [TH]

87And bear a Crippled Carcass through the Skie.

88'Tis this exalted pow'rpower, whose

bus'ness lies,

powerRochester

refers here to reason as the falsely "exalted pow'r." The remainder of the poem

will lay out why the poet thinks so. - [TH]

89In Nonsense, and impossibilities.

90This made a Whimsical Philosopher,

91Before the spacious World, his Tubtub prefer

tubThe word tub has a lot of meanings during this period. Proverbially,

it is used to refer to a fiction, or a made-up story; but it also specifically

refers to the pulpit from which a non-conformist preacher spoke. Nonconformity

refers to any religious faith not strictly Anglican. It also has another meaning

that

Rochester would have known about--a "sweating-tub" or a sort of barrel

encasing the

body used specifically to treat venereal disease. See the

OED. - [TH]

92And we have modern Cloysterd Coxcombs, who

93Retire to think, cause they have naught to do.

94But thoughts, are giv'n for Actions government,

95Where Action ceases, thoughts impertinent:

96Our Sphere of

Action, is lifes happiness,action

actionRochester became identified with philosophical and sexual libertinism of the

Restoration, which was characterized by the public, even performative pursuit of

pleasure and a vivid, almost nihilistic sexuality. Libertinism was underpinned by

a selective reading of Thomas Hobbes' theory of human nature. Hobbes, according to

Christopher Tilmouth, "declar[ed] that the passions, not reason, constituted the

proper, primary determinants of human conduct" and "posited...a new ideal of

happiness, equating felicity with a constant motion of the self from the

satisfaction of one appetite to the next, and he accorded fear and the lust for

power critical roles in this kinetic process" (Tilmouth 4-5).

Hobbes

characterized humankind in nature as in a permanent state of conflict and

struggle, governed by their appetites and their passions, and to avoid this

chaotic, violent state of nature, human societies contract with strong leaders to

bring order to passion and law to desire: "it is manifest that, during the time

men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that

condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every

man" (Leviathan, XIII, para. 8). Rochester positions his

libertinism as a moral freedom beyond the civil codes of contractual law. For more

on Restoration libertinism, see James Turner, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London, especially

chapter 6; and Diane Maybank'sarticle for the British Library about libertinism on the

Restoration stage. - [TH]

97And he who thinks Beyond, thinks like an Ass.

98Thus, whilst' gainst false reas'ning I inveigh,

99I own right Reason, which I wou'd obey:

100That Reason

that distinguishes by sensereasons,

reasonsRochester compares his materialist sense of reason--reason that rightly

"distinguishes by sense [perception]"--to the flawed or "false" reason of the

pedantic curate, that starts with the "beyond" (97). - [TH]

101And gives us Rules, of good, and ill from

thence:

102That bounds desires, with a reforming Will,

103To keep 'em more in vigour, not to kill.

104Your Reason hinders, mine helps t'enjoy,

105Renewing Apetites, yours wou'd destroy.

10

106My Reasons is my Friend, yours is a Cheat,

107Hungar call's out, my Reason bids me eat;

108Perversly yours, your Appetite does mock,

109This askt for Food, that answers what's a Clock?