"Satyr [Against Reason and Mankind]"

By

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students and Staff of Marymount University, Jordan Lawton

author John Wilmot,

second earl of Rochester, was born to Anne St. John, Countess of Rochester and

Henry Wilmot, first earl of Rochester on April 1st, 1647, in Oxfordshire,

England. In 1658, at age eleven, John Wilmot succeeded his fathers’ Earldom.

Just three years later, Wilmot received an M.A. from Wadham College, Oxford.

Charles II, King of Great Britain and Ireland at the time, appointed Rochester

a tutor to be mentored by. Rochester and his tutor, Sir Andrew Balfour

travelled through France and Italy until 1664 when Rochester returned to

Charles’ court. In his time at court, Wilmot became one of the most famous

poets and controversial satirists of the Restoration period. In the collection

The Poems of John Wilmot, editor Keith Walker notes

that Rochester’s raucous lifestyle and many vices--some characteristics of his

libertinism--often garnered contempt from the king’s court. Though he was a

notable poet, Rochester acted as a patron to many playwrights including John

Dryden and John Fletcher. The latter part of the 1670s saw Rochester contribute

more seriously to the affairs of the state. On his deathbed, Rochester is said

to have called upon his close friend, the bishop of Salisbury, Gilbert Burnet,

to recant his past libertinism and convert to Christianity. Rochester died on

July 26th, 1680, in Oxfordshire, at the age of thirty-three. The image included

here (NPG 804), licensed under Creative Commons, is a portrait in oil on canvas

of John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester by an unknown artist (c.1665-1670), via

the National Portrait Gallery, UK. As the notes to the portrait point out, "This portrait has a

satirical message almost certainly of Rochester's devising. It portrays him,

manuscript in hand, bestowing the poet's laurels on a jabbering monkey who is

tearing out the pages of a book and handing them crumpled to the

poet." - [JL]Antwerp

'Antwerp’ is a false imprint. James Thorpe discusses this interesting detail in

The Earliest Editions of

Rochester’s Poems" noting that the printings were “unlicensed books

printed in London” where the false imprint was used for “simple subterfuge

presumably intended to attract the lovers of racy literature or distract

prosecution”. - [JL]grossIn

this sense, gross refers to materiality as distinct from ethereality or

spirituality. See OED adj III.8.c: describes "things material or perceptible to

the senses, as contrasted with what is spiritual, ethereal, or impalpable." - [MUStudStaff]ignus-fatuusFrom the Latin meaning, literally, "foolish fire," an

ignis fatuus is a will-o'the-wisp, a flitting phosphorescent light that led

travelers astray in marshy areas like the "Fenny Bogs and Thorny Brakes" (15)

Rochester describes below (OED, "ignis fatuus,

n."). - [JL]wrongLines

29-36 explain how, from Rochester's perspective, this approach to life that prizes

reason is "in the wrong." - [TH]reasonThe

"reasoning Enging" is the mind--here, Rochester notes that the mind is "huddled in

[the] dirt" of the physical body. The body and the mind are intertwined, rather

than separate. - [TH]bubblesHere used

as a noun, "bubbles" in this sense refers to those who have been fooled or cheated

(OED, n.2b). - [TH]wits During the Restoration period in England, Charles II

would often be found in the company of young intellectuals or "wits." In The Court Wits of the Restoration, John Harold Wilson

writes that “the label Wit was attached only to one who made some real pretense

to distinction as a poet, critic, translator, raconteur, or a man of learning"

(6). Among the so-called "court wits" were Rochester, Sir John

Suckling, Edmund Waller, and others. [add paraphrase from page 5 of Tilmouth:

https://books.google.com/books?id=DipmhwkFfQMC - [JL]pleasureAs

Jeremy Webster argues in Performing Libertinism in Charles II’s

Court, “[l]ibertines...performed traditionally secretive acts— excessive

drinking, carnality, sodomy, sedition, assault, and sacrilege—in the public sphere

in a variety of ways” (2). Here, Rochester is talking in part about sexual

pleasure that, once enjoyed, brings causes the enjoyer to fear or hate that

pleasure. This fear is in part existential or philosophical--pleasure brings with

it "dang'rous" (41) questions about the value of social order founded on

reason--but it is also material, as in the fear of sexually transmitted infection,

from which Rochester sufferred. The "succeeding pains" (40) to which he refers

encapsulate both kinds of fears. - [TH]fopsIn "Fops and Some Versions of Foppery,"

Robert B. Heilman discusses this term, noting that as a “general, all-purpose

carrier of disapproval, fop works much like fool" (364). - [JL]band

John Wilmot,

second earl of Rochester, was born to Anne St. John, Countess of Rochester and

Henry Wilmot, first earl of Rochester on April 1st, 1647, in Oxfordshire,

England. In 1658, at age eleven, John Wilmot succeeded his fathers’ Earldom.

Just three years later, Wilmot received an M.A. from Wadham College, Oxford.

Charles II, King of Great Britain and Ireland at the time, appointed Rochester

a tutor to be mentored by. Rochester and his tutor, Sir Andrew Balfour

travelled through France and Italy until 1664 when Rochester returned to

Charles’ court. In his time at court, Wilmot became one of the most famous

poets and controversial satirists of the Restoration period. In the collection

The Poems of John Wilmot, editor Keith Walker notes

that Rochester’s raucous lifestyle and many vices--some characteristics of his

libertinism--often garnered contempt from the king’s court. Though he was a

notable poet, Rochester acted as a patron to many playwrights including John

Dryden and John Fletcher. The latter part of the 1670s saw Rochester contribute

more seriously to the affairs of the state. On his deathbed, Rochester is said

to have called upon his close friend, the bishop of Salisbury, Gilbert Burnet,

to recant his past libertinism and convert to Christianity. Rochester died on

July 26th, 1680, in Oxfordshire, at the age of thirty-three. The image included

here (NPG 804), licensed under Creative Commons, is a portrait in oil on canvas

of John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester by an unknown artist (c.1665-1670), via

the National Portrait Gallery, UK. As the notes to the portrait point out, "This portrait has a

satirical message almost certainly of Rochester's devising. It portrays him,

manuscript in hand, bestowing the poet's laurels on a jabbering monkey who is

tearing out the pages of a book and handing them crumpled to the

poet." - [JL]Antwerp

'Antwerp’ is a false imprint. James Thorpe discusses this interesting detail in

The Earliest Editions of

Rochester’s Poems" noting that the printings were “unlicensed books

printed in London” where the false imprint was used for “simple subterfuge

presumably intended to attract the lovers of racy literature or distract

prosecution”. - [JL]grossIn

this sense, gross refers to materiality as distinct from ethereality or

spirituality. See OED adj III.8.c: describes "things material or perceptible to

the senses, as contrasted with what is spiritual, ethereal, or impalpable." - [MUStudStaff]ignus-fatuusFrom the Latin meaning, literally, "foolish fire," an

ignis fatuus is a will-o'the-wisp, a flitting phosphorescent light that led

travelers astray in marshy areas like the "Fenny Bogs and Thorny Brakes" (15)

Rochester describes below (OED, "ignis fatuus,

n."). - [JL]wrongLines

29-36 explain how, from Rochester's perspective, this approach to life that prizes

reason is "in the wrong." - [TH]reasonThe

"reasoning Enging" is the mind--here, Rochester notes that the mind is "huddled in

[the] dirt" of the physical body. The body and the mind are intertwined, rather

than separate. - [TH]bubblesHere used

as a noun, "bubbles" in this sense refers to those who have been fooled or cheated

(OED, n.2b). - [TH]wits During the Restoration period in England, Charles II

would often be found in the company of young intellectuals or "wits." In The Court Wits of the Restoration, John Harold Wilson

writes that “the label Wit was attached only to one who made some real pretense

to distinction as a poet, critic, translator, raconteur, or a man of learning"

(6). Among the so-called "court wits" were Rochester, Sir John

Suckling, Edmund Waller, and others. [add paraphrase from page 5 of Tilmouth:

https://books.google.com/books?id=DipmhwkFfQMC - [JL]pleasureAs

Jeremy Webster argues in Performing Libertinism in Charles II’s

Court, “[l]ibertines...performed traditionally secretive acts— excessive

drinking, carnality, sodomy, sedition, assault, and sacrilege—in the public sphere

in a variety of ways” (2). Here, Rochester is talking in part about sexual

pleasure that, once enjoyed, brings causes the enjoyer to fear or hate that

pleasure. This fear is in part existential or philosophical--pleasure brings with

it "dang'rous" (41) questions about the value of social order founded on

reason--but it is also material, as in the fear of sexually transmitted infection,

from which Rochester sufferred. The "succeeding pains" (40) to which he refers

encapsulate both kinds of fears. - [TH]fopsIn "Fops and Some Versions of Foppery,"

Robert B. Heilman discusses this term, noting that as a “general, all-purpose

carrier of disapproval, fop works much like fool" (364). - [JL]band According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

) - [JL]libertinismFor Margaret Ezell,

who writes about the performative quality of Restoration libertinism, Rochester's

libertinism was a deliberate assertion of privilege designed to cultivate power in

the court ("Enacting Libertinism: Court Performance and Literary Culture" in The Oxford English Literary History, Vol. V.). Rochester's

poem is a response to the question being asked here by a hypothetical clergyman

(the "formal band and beard"). Here, he is performing the persona of the pedantic,

prudish curate ultimately to mock him and his moral philosophy, thereby

cultivating a witty superiority.rageThe

clergyman describes Rochester's mind as "degen[e]rate," and his way of thinking,

deviant. Rochester’s poem is a “Satire against Reason and Mankind”; it is

fundamentally skeptical of the ability--or desirability--of reason and law to

ameliorate baser human interests. - [TH]speakerAt this point, Rochester's character speaks,

returning a satirical answer to the pedantic curate.Ignello

Nathaniel

Ingelo, born ca 1621. Graduate and fellow of the Queen’s College,

Cambridge. Ingelo was a clergyman and author of a religious romance entitled Bentivolio and Urania. Marianne Thormählen writes in aRochester: The Poems in Context that the works of Ingelo and Simon

Patrick mentioned below would have been well known during Rochester’s time. She

mentions that Rochester would have detested “Ingelo’s exalted view of man; and his

attacks on Epicurus and his followers”.pSimon Patrick, Bishop of Ely (1626-1707) was an English

theologian and, eventually, bishop; his book The Parable of

the Pilgrim (1663/4) is referenced here. Patrick's Pilgrim is an allegory along the same lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Patrick’s first assignment after

graduating from Queen's College, Cambridge, was as a domestic chaplain to Sir

Walter St. John, John Wilmot’s uncle (Dictionary of National Biography)> - [TH]sRichard Sibbes

(1577-1635), was a popular Puritan theologian, minister, and writer, in the

affective tradition with intellectual connections to Calvinism. He is most well

known for a work called The Bruised Reed, but Rochester

here references a work this editor has not been able to trace. Other editions of

the poem replace "replies" with "soliloquies," possibly suggesting a different

work, Richard Bayne's Holy Soliloquies (1637)--Sibbes wa

very influenced by Bayne. Regardless, all of these references are to popular

theologians during the 17th century. . He, too, studied at Cambridge, but his

Puritanism caused him to lose a lectureship there (Dictionary of National Biography). - [TH]bedlamBedlam is

the colloquial term for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, an asylum for the

mentally ill first established in 1676. It was often used as a broader term for

any location of perceived insanity. - [TH]sotA sot is a stupid

person, usually someone who is "stupified" with liquor or habitually drunk

(OED). - [TH]comparisonRochester compares the inflated ideology of the pedantic curate--whose "business"

is "Nonsense" and "impossibilities" (86)--with the superstitions that give witches

the power of flight. - [TH]powerRochester

refers here to reason as the falsely "exalted pow'r." The remainder of the poem

will lay out why the poet thinks so. - [TH]tubThe word tub has a lot of meanings during this period. Proverbially,

it is used to refer to a fiction, or a made-up story; but it also specifically

refers to the pulpit from which a non-conformist preacher spoke. Nonconformity

refers to any religious faith not strictly Anglican. It also has another meaning

that

Rochester would have known about--a "sweating-tub" or a sort of barrel

encasing the

body used specifically to treat venereal disease. See the

OED. - [TH]actionRochester became identified with philosophical and sexual libertinism of the

Restoration, which was characterized by the public, even performative pursuit of

pleasure and a vivid, almost nihilistic sexuality. Libertinism was underpinned by

a selective reading of Thomas Hobbes' theory of human nature. Hobbes, according to

Christopher Tilmouth, "declar[ed] that the passions, not reason, constituted the

proper, primary determinants of human conduct" and "posited...a new ideal of

happiness, equating felicity with a constant motion of the self from the

satisfaction of one appetite to the next, and he accorded fear and the lust for

power critical roles in this kinetic process" (Tilmouth 4-5).

Hobbes

characterized humankind in nature as in a permanent state of conflict and

struggle, governed by their appetites and their passions, and to avoid this

chaotic, violent state of nature, human societies contract with strong leaders to

bring order to passion and law to desire: "it is manifest that, during the time

men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that

condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every

man" (Leviathan, XIII, para. 8). Rochester positions his

libertinism as a moral freedom beyond the civil codes of contractual law. For more

on Restoration libertinism, see James Turner, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London, especially

chapter 6; and Diane Maybank'sarticle for the British Library about libertinism on the

Restoration stage. - [TH]reasonsRochester compares his materialist sense of reason--reason that rightly

"distinguishes by sense [perception]"--to the flawed or "false" reason of the

pedantic curate, that starts with the "beyond" (97). - [TH]jowlerA common

name for a dog. - [TH]mM-- is Henry

More, a rationalist Cartesian theologian who argues that God orders the world

infallibly and always according to the best ends ("the best of all possible

worlds"). He wrote several books, including On the Immortality

of the Soul, where he sought to counter the Hobbesian view of life outside

of society as "nasty, brutish, and short" and instead to prove "the exsitence of

immaterial substance, or spirit, and therefore God" (Stanford Encyclopedia

of Philosophy); he is most well known for his idea of the Spirit of

Nature, which connected the material world to the spiritual. Like other Platonists

of the 17th century, he believed that the immortality of the soul proved an

afterlife, characterized by damnation or salvation. Rochester disagreed with this

perspective. - [TH]beastsIn the

following lines, Rochester sets up an extended comparison between the nature of

violence in the animal kingdom and in the human world. - [TH]square"To play

upon the square" means to play fairly (or "fair and square," in current colloquial

terms). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this expression was "[v]ery

common from c1670, frequently with reference to...gaming" ("square," adj.,

III.12.b). - [TH]dashesDuring this period, dashes were often used to

visibly omit a name that would identify the subject of satire. Usually,

contemporary readers would have understood who the author was referring to.natureIn Leviathan (1651), Hobbes argued that humans are completely

driven by the primary drives of appetite and aversion; people are selfish at their

root. In the state of nature, which is a state of war, “there is no place for

industry...; no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is

worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man

solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Paragraph 9, Chapter 13, Leviathan). - [TH]slavesRochester suggests that "the pretending part of the proud World" (175) use their

supposed spiritual superiority to weild tyrranical power over other people, not

recognizing that everyone is a "Slave." - [TH]courtCourt

here, as elsewhere, refers to the court of nobles and other people of power

surrounding King Charles II (or whomever was monarch at the time). Court culture,

in the Restoration, was often characterized both by stringent absolutism and a

permissiveness that distinguished those of privilege. To read more about

Restoration court culture, see Culture and Politics at the Court of Charles II,

1660-1685, by Matthew Jenkinson. - [TH]aurealReaders may

be more familiar with the noun form ("aura") of this obsolete adjective. "Aureal

Bribes" are bribes that are gilded or golden (OED). - [TH]bOther versions of Rochester's poem

replace the initial with "bishops."fourscoreA unit

of measurement, usually of time. A "score" is twenty; so, four score is four times

twenty, or eighty. - [TH]ifRochester here

makes an IF/THEN logical statement. If such "[in]conceiv[ably]" (218) "meek humble

M[e]n, of modest sense" (215) can be revealed, he'll "recant" (220) this poetic

statement. - [TH]rabble"Rabble" here is used as a

derogatory term to refer to the masses or the common people--and "their Laws"

(222)--from which mob Rochester distances himself through his libertinism. See the

OED "rabble," n.1 and adj., particularly sense 3.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

) - [JL]libertinismFor Margaret Ezell,

who writes about the performative quality of Restoration libertinism, Rochester's

libertinism was a deliberate assertion of privilege designed to cultivate power in

the court ("Enacting Libertinism: Court Performance and Literary Culture" in The Oxford English Literary History, Vol. V.). Rochester's

poem is a response to the question being asked here by a hypothetical clergyman

(the "formal band and beard"). Here, he is performing the persona of the pedantic,

prudish curate ultimately to mock him and his moral philosophy, thereby

cultivating a witty superiority.rageThe

clergyman describes Rochester's mind as "degen[e]rate," and his way of thinking,

deviant. Rochester’s poem is a “Satire against Reason and Mankind”; it is

fundamentally skeptical of the ability--or desirability--of reason and law to

ameliorate baser human interests. - [TH]speakerAt this point, Rochester's character speaks,

returning a satirical answer to the pedantic curate.Ignello

Nathaniel

Ingelo, born ca 1621. Graduate and fellow of the Queen’s College,

Cambridge. Ingelo was a clergyman and author of a religious romance entitled Bentivolio and Urania. Marianne Thormählen writes in aRochester: The Poems in Context that the works of Ingelo and Simon

Patrick mentioned below would have been well known during Rochester’s time. She

mentions that Rochester would have detested “Ingelo’s exalted view of man; and his

attacks on Epicurus and his followers”.pSimon Patrick, Bishop of Ely (1626-1707) was an English

theologian and, eventually, bishop; his book The Parable of

the Pilgrim (1663/4) is referenced here. Patrick's Pilgrim is an allegory along the same lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Patrick’s first assignment after

graduating from Queen's College, Cambridge, was as a domestic chaplain to Sir

Walter St. John, John Wilmot’s uncle (Dictionary of National Biography)> - [TH]sRichard Sibbes

(1577-1635), was a popular Puritan theologian, minister, and writer, in the

affective tradition with intellectual connections to Calvinism. He is most well

known for a work called The Bruised Reed, but Rochester

here references a work this editor has not been able to trace. Other editions of

the poem replace "replies" with "soliloquies," possibly suggesting a different

work, Richard Bayne's Holy Soliloquies (1637)--Sibbes wa

very influenced by Bayne. Regardless, all of these references are to popular

theologians during the 17th century. . He, too, studied at Cambridge, but his

Puritanism caused him to lose a lectureship there (Dictionary of National Biography). - [TH]bedlamBedlam is

the colloquial term for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, an asylum for the

mentally ill first established in 1676. It was often used as a broader term for

any location of perceived insanity. - [TH]sotA sot is a stupid

person, usually someone who is "stupified" with liquor or habitually drunk

(OED). - [TH]comparisonRochester compares the inflated ideology of the pedantic curate--whose "business"

is "Nonsense" and "impossibilities" (86)--with the superstitions that give witches

the power of flight. - [TH]powerRochester

refers here to reason as the falsely "exalted pow'r." The remainder of the poem

will lay out why the poet thinks so. - [TH]tubThe word tub has a lot of meanings during this period. Proverbially,

it is used to refer to a fiction, or a made-up story; but it also specifically

refers to the pulpit from which a non-conformist preacher spoke. Nonconformity

refers to any religious faith not strictly Anglican. It also has another meaning

that

Rochester would have known about--a "sweating-tub" or a sort of barrel

encasing the

body used specifically to treat venereal disease. See the

OED. - [TH]actionRochester became identified with philosophical and sexual libertinism of the

Restoration, which was characterized by the public, even performative pursuit of

pleasure and a vivid, almost nihilistic sexuality. Libertinism was underpinned by

a selective reading of Thomas Hobbes' theory of human nature. Hobbes, according to

Christopher Tilmouth, "declar[ed] that the passions, not reason, constituted the

proper, primary determinants of human conduct" and "posited...a new ideal of

happiness, equating felicity with a constant motion of the self from the

satisfaction of one appetite to the next, and he accorded fear and the lust for

power critical roles in this kinetic process" (Tilmouth 4-5).

Hobbes

characterized humankind in nature as in a permanent state of conflict and

struggle, governed by their appetites and their passions, and to avoid this

chaotic, violent state of nature, human societies contract with strong leaders to

bring order to passion and law to desire: "it is manifest that, during the time

men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that

condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every

man" (Leviathan, XIII, para. 8). Rochester positions his

libertinism as a moral freedom beyond the civil codes of contractual law. For more

on Restoration libertinism, see James Turner, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London, especially

chapter 6; and Diane Maybank'sarticle for the British Library about libertinism on the

Restoration stage. - [TH]reasonsRochester compares his materialist sense of reason--reason that rightly

"distinguishes by sense [perception]"--to the flawed or "false" reason of the

pedantic curate, that starts with the "beyond" (97). - [TH]jowlerA common

name for a dog. - [TH]mM-- is Henry

More, a rationalist Cartesian theologian who argues that God orders the world

infallibly and always according to the best ends ("the best of all possible

worlds"). He wrote several books, including On the Immortality

of the Soul, where he sought to counter the Hobbesian view of life outside

of society as "nasty, brutish, and short" and instead to prove "the exsitence of

immaterial substance, or spirit, and therefore God" (Stanford Encyclopedia

of Philosophy); he is most well known for his idea of the Spirit of

Nature, which connected the material world to the spiritual. Like other Platonists

of the 17th century, he believed that the immortality of the soul proved an

afterlife, characterized by damnation or salvation. Rochester disagreed with this

perspective. - [TH]beastsIn the

following lines, Rochester sets up an extended comparison between the nature of

violence in the animal kingdom and in the human world. - [TH]square"To play

upon the square" means to play fairly (or "fair and square," in current colloquial

terms). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this expression was "[v]ery

common from c1670, frequently with reference to...gaming" ("square," adj.,

III.12.b). - [TH]dashesDuring this period, dashes were often used to

visibly omit a name that would identify the subject of satire. Usually,

contemporary readers would have understood who the author was referring to.natureIn Leviathan (1651), Hobbes argued that humans are completely

driven by the primary drives of appetite and aversion; people are selfish at their

root. In the state of nature, which is a state of war, “there is no place for

industry...; no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is

worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man

solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Paragraph 9, Chapter 13, Leviathan). - [TH]slavesRochester suggests that "the pretending part of the proud World" (175) use their

supposed spiritual superiority to weild tyrranical power over other people, not

recognizing that everyone is a "Slave." - [TH]courtCourt

here, as elsewhere, refers to the court of nobles and other people of power

surrounding King Charles II (or whomever was monarch at the time). Court culture,

in the Restoration, was often characterized both by stringent absolutism and a

permissiveness that distinguished those of privilege. To read more about

Restoration court culture, see Culture and Politics at the Court of Charles II,

1660-1685, by Matthew Jenkinson. - [TH]aurealReaders may

be more familiar with the noun form ("aura") of this obsolete adjective. "Aureal

Bribes" are bribes that are gilded or golden (OED). - [TH]bOther versions of Rochester's poem

replace the initial with "bishops."fourscoreA unit

of measurement, usually of time. A "score" is twenty; so, four score is four times

twenty, or eighty. - [TH]ifRochester here

makes an IF/THEN logical statement. If such "[in]conceiv[ably]" (218) "meek humble

M[e]n, of modest sense" (215) can be revealed, he'll "recant" (220) this poetic

statement. - [TH]rabble"Rabble" here is used as a

derogatory term to refer to the masses or the common people--and "their Laws"

(222)--from which mob Rochester distances himself through his libertinism. See the

OED "rabble," n.1 and adj., particularly sense 3.

John Wilmot,

second earl of Rochester, was born to Anne St. John, Countess of Rochester and

Henry Wilmot, first earl of Rochester on April 1st, 1647, in Oxfordshire,

England. In 1658, at age eleven, John Wilmot succeeded his fathers’ Earldom.

Just three years later, Wilmot received an M.A. from Wadham College, Oxford.

Charles II, King of Great Britain and Ireland at the time, appointed Rochester

a tutor to be mentored by. Rochester and his tutor, Sir Andrew Balfour

travelled through France and Italy until 1664 when Rochester returned to

Charles’ court. In his time at court, Wilmot became one of the most famous

poets and controversial satirists of the Restoration period. In the collection

The Poems of John Wilmot, editor Keith Walker notes

that Rochester’s raucous lifestyle and many vices--some characteristics of his

libertinism--often garnered contempt from the king’s court. Though he was a

notable poet, Rochester acted as a patron to many playwrights including John

Dryden and John Fletcher. The latter part of the 1670s saw Rochester contribute

more seriously to the affairs of the state. On his deathbed, Rochester is said

to have called upon his close friend, the bishop of Salisbury, Gilbert Burnet,

to recant his past libertinism and convert to Christianity. Rochester died on

July 26th, 1680, in Oxfordshire, at the age of thirty-three. The image included

here (NPG 804), licensed under Creative Commons, is a portrait in oil on canvas

of John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester by an unknown artist (c.1665-1670), via

the National Portrait Gallery, UK. As the notes to the portrait point out, "This portrait has a

satirical message almost certainly of Rochester's devising. It portrays him,

manuscript in hand, bestowing the poet's laurels on a jabbering monkey who is

tearing out the pages of a book and handing them crumpled to the

poet." - [JL]Antwerp

'Antwerp’ is a false imprint. James Thorpe discusses this interesting detail in

The Earliest Editions of

Rochester’s Poems" noting that the printings were “unlicensed books

printed in London” where the false imprint was used for “simple subterfuge

presumably intended to attract the lovers of racy literature or distract

prosecution”. - [JL]grossIn

this sense, gross refers to materiality as distinct from ethereality or

spirituality. See OED adj III.8.c: describes "things material or perceptible to

the senses, as contrasted with what is spiritual, ethereal, or impalpable." - [MUStudStaff]ignus-fatuusFrom the Latin meaning, literally, "foolish fire," an

ignis fatuus is a will-o'the-wisp, a flitting phosphorescent light that led

travelers astray in marshy areas like the "Fenny Bogs and Thorny Brakes" (15)

Rochester describes below (OED, "ignis fatuus,

n."). - [JL]wrongLines

29-36 explain how, from Rochester's perspective, this approach to life that prizes

reason is "in the wrong." - [TH]reasonThe

"reasoning Enging" is the mind--here, Rochester notes that the mind is "huddled in

[the] dirt" of the physical body. The body and the mind are intertwined, rather

than separate. - [TH]bubblesHere used

as a noun, "bubbles" in this sense refers to those who have been fooled or cheated

(OED, n.2b). - [TH]wits During the Restoration period in England, Charles II

would often be found in the company of young intellectuals or "wits." In The Court Wits of the Restoration, John Harold Wilson

writes that “the label Wit was attached only to one who made some real pretense

to distinction as a poet, critic, translator, raconteur, or a man of learning"

(6). Among the so-called "court wits" were Rochester, Sir John

Suckling, Edmund Waller, and others. [add paraphrase from page 5 of Tilmouth:

https://books.google.com/books?id=DipmhwkFfQMC - [JL]pleasureAs

Jeremy Webster argues in Performing Libertinism in Charles II’s

Court, “[l]ibertines...performed traditionally secretive acts— excessive

drinking, carnality, sodomy, sedition, assault, and sacrilege—in the public sphere

in a variety of ways” (2). Here, Rochester is talking in part about sexual

pleasure that, once enjoyed, brings causes the enjoyer to fear or hate that

pleasure. This fear is in part existential or philosophical--pleasure brings with

it "dang'rous" (41) questions about the value of social order founded on

reason--but it is also material, as in the fear of sexually transmitted infection,

from which Rochester sufferred. The "succeeding pains" (40) to which he refers

encapsulate both kinds of fears. - [TH]fopsIn "Fops and Some Versions of Foppery,"

Robert B. Heilman discusses this term, noting that as a “general, all-purpose

carrier of disapproval, fop works much like fool" (364). - [JL]band

John Wilmot,

second earl of Rochester, was born to Anne St. John, Countess of Rochester and

Henry Wilmot, first earl of Rochester on April 1st, 1647, in Oxfordshire,

England. In 1658, at age eleven, John Wilmot succeeded his fathers’ Earldom.

Just three years later, Wilmot received an M.A. from Wadham College, Oxford.

Charles II, King of Great Britain and Ireland at the time, appointed Rochester

a tutor to be mentored by. Rochester and his tutor, Sir Andrew Balfour

travelled through France and Italy until 1664 when Rochester returned to

Charles’ court. In his time at court, Wilmot became one of the most famous

poets and controversial satirists of the Restoration period. In the collection

The Poems of John Wilmot, editor Keith Walker notes

that Rochester’s raucous lifestyle and many vices--some characteristics of his

libertinism--often garnered contempt from the king’s court. Though he was a

notable poet, Rochester acted as a patron to many playwrights including John

Dryden and John Fletcher. The latter part of the 1670s saw Rochester contribute

more seriously to the affairs of the state. On his deathbed, Rochester is said

to have called upon his close friend, the bishop of Salisbury, Gilbert Burnet,

to recant his past libertinism and convert to Christianity. Rochester died on

July 26th, 1680, in Oxfordshire, at the age of thirty-three. The image included

here (NPG 804), licensed under Creative Commons, is a portrait in oil on canvas

of John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester by an unknown artist (c.1665-1670), via

the National Portrait Gallery, UK. As the notes to the portrait point out, "This portrait has a

satirical message almost certainly of Rochester's devising. It portrays him,

manuscript in hand, bestowing the poet's laurels on a jabbering monkey who is

tearing out the pages of a book and handing them crumpled to the

poet." - [JL]Antwerp

'Antwerp’ is a false imprint. James Thorpe discusses this interesting detail in

The Earliest Editions of

Rochester’s Poems" noting that the printings were “unlicensed books

printed in London” where the false imprint was used for “simple subterfuge

presumably intended to attract the lovers of racy literature or distract

prosecution”. - [JL]grossIn

this sense, gross refers to materiality as distinct from ethereality or

spirituality. See OED adj III.8.c: describes "things material or perceptible to

the senses, as contrasted with what is spiritual, ethereal, or impalpable." - [MUStudStaff]ignus-fatuusFrom the Latin meaning, literally, "foolish fire," an

ignis fatuus is a will-o'the-wisp, a flitting phosphorescent light that led

travelers astray in marshy areas like the "Fenny Bogs and Thorny Brakes" (15)

Rochester describes below (OED, "ignis fatuus,

n."). - [JL]wrongLines

29-36 explain how, from Rochester's perspective, this approach to life that prizes

reason is "in the wrong." - [TH]reasonThe

"reasoning Enging" is the mind--here, Rochester notes that the mind is "huddled in

[the] dirt" of the physical body. The body and the mind are intertwined, rather

than separate. - [TH]bubblesHere used

as a noun, "bubbles" in this sense refers to those who have been fooled or cheated

(OED, n.2b). - [TH]wits During the Restoration period in England, Charles II

would often be found in the company of young intellectuals or "wits." In The Court Wits of the Restoration, John Harold Wilson

writes that “the label Wit was attached only to one who made some real pretense

to distinction as a poet, critic, translator, raconteur, or a man of learning"

(6). Among the so-called "court wits" were Rochester, Sir John

Suckling, Edmund Waller, and others. [add paraphrase from page 5 of Tilmouth:

https://books.google.com/books?id=DipmhwkFfQMC - [JL]pleasureAs

Jeremy Webster argues in Performing Libertinism in Charles II’s

Court, “[l]ibertines...performed traditionally secretive acts— excessive

drinking, carnality, sodomy, sedition, assault, and sacrilege—in the public sphere

in a variety of ways” (2). Here, Rochester is talking in part about sexual

pleasure that, once enjoyed, brings causes the enjoyer to fear or hate that

pleasure. This fear is in part existential or philosophical--pleasure brings with

it "dang'rous" (41) questions about the value of social order founded on

reason--but it is also material, as in the fear of sexually transmitted infection,

from which Rochester sufferred. The "succeeding pains" (40) to which he refers

encapsulate both kinds of fears. - [TH]fopsIn "Fops and Some Versions of Foppery,"

Robert B. Heilman discusses this term, noting that as a “general, all-purpose

carrier of disapproval, fop works much like fool" (364). - [JL]band According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

) - [JL]libertinismFor Margaret Ezell,

who writes about the performative quality of Restoration libertinism, Rochester's

libertinism was a deliberate assertion of privilege designed to cultivate power in

the court ("Enacting Libertinism: Court Performance and Literary Culture" in The Oxford English Literary History, Vol. V.). Rochester's

poem is a response to the question being asked here by a hypothetical clergyman

(the "formal band and beard"). Here, he is performing the persona of the pedantic,

prudish curate ultimately to mock him and his moral philosophy, thereby

cultivating a witty superiority.rageThe

clergyman describes Rochester's mind as "degen[e]rate," and his way of thinking,

deviant. Rochester’s poem is a “Satire against Reason and Mankind”; it is

fundamentally skeptical of the ability--or desirability--of reason and law to

ameliorate baser human interests. - [TH]speakerAt this point, Rochester's character speaks,

returning a satirical answer to the pedantic curate.Ignello

Nathaniel

Ingelo, born ca 1621. Graduate and fellow of the Queen’s College,

Cambridge. Ingelo was a clergyman and author of a religious romance entitled Bentivolio and Urania. Marianne Thormählen writes in aRochester: The Poems in Context that the works of Ingelo and Simon

Patrick mentioned below would have been well known during Rochester’s time. She

mentions that Rochester would have detested “Ingelo’s exalted view of man; and his

attacks on Epicurus and his followers”.pSimon Patrick, Bishop of Ely (1626-1707) was an English

theologian and, eventually, bishop; his book The Parable of

the Pilgrim (1663/4) is referenced here. Patrick's Pilgrim is an allegory along the same lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Patrick’s first assignment after

graduating from Queen's College, Cambridge, was as a domestic chaplain to Sir

Walter St. John, John Wilmot’s uncle (Dictionary of National Biography)> - [TH]sRichard Sibbes

(1577-1635), was a popular Puritan theologian, minister, and writer, in the

affective tradition with intellectual connections to Calvinism. He is most well

known for a work called The Bruised Reed, but Rochester

here references a work this editor has not been able to trace. Other editions of

the poem replace "replies" with "soliloquies," possibly suggesting a different

work, Richard Bayne's Holy Soliloquies (1637)--Sibbes wa

very influenced by Bayne. Regardless, all of these references are to popular

theologians during the 17th century. . He, too, studied at Cambridge, but his

Puritanism caused him to lose a lectureship there (Dictionary of National Biography). - [TH]bedlamBedlam is

the colloquial term for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, an asylum for the

mentally ill first established in 1676. It was often used as a broader term for

any location of perceived insanity. - [TH]sotA sot is a stupid

person, usually someone who is "stupified" with liquor or habitually drunk

(OED). - [TH]comparisonRochester compares the inflated ideology of the pedantic curate--whose "business"

is "Nonsense" and "impossibilities" (86)--with the superstitions that give witches

the power of flight. - [TH]powerRochester

refers here to reason as the falsely "exalted pow'r." The remainder of the poem

will lay out why the poet thinks so. - [TH]tubThe word tub has a lot of meanings during this period. Proverbially,

it is used to refer to a fiction, or a made-up story; but it also specifically

refers to the pulpit from which a non-conformist preacher spoke. Nonconformity

refers to any religious faith not strictly Anglican. It also has another meaning

that

Rochester would have known about--a "sweating-tub" or a sort of barrel

encasing the

body used specifically to treat venereal disease. See the

OED. - [TH]actionRochester became identified with philosophical and sexual libertinism of the

Restoration, which was characterized by the public, even performative pursuit of

pleasure and a vivid, almost nihilistic sexuality. Libertinism was underpinned by

a selective reading of Thomas Hobbes' theory of human nature. Hobbes, according to

Christopher Tilmouth, "declar[ed] that the passions, not reason, constituted the

proper, primary determinants of human conduct" and "posited...a new ideal of

happiness, equating felicity with a constant motion of the self from the

satisfaction of one appetite to the next, and he accorded fear and the lust for

power critical roles in this kinetic process" (Tilmouth 4-5).

Hobbes

characterized humankind in nature as in a permanent state of conflict and

struggle, governed by their appetites and their passions, and to avoid this

chaotic, violent state of nature, human societies contract with strong leaders to

bring order to passion and law to desire: "it is manifest that, during the time

men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that

condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every

man" (Leviathan, XIII, para. 8). Rochester positions his

libertinism as a moral freedom beyond the civil codes of contractual law. For more

on Restoration libertinism, see James Turner, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London, especially

chapter 6; and Diane Maybank'sarticle for the British Library about libertinism on the

Restoration stage. - [TH]reasonsRochester compares his materialist sense of reason--reason that rightly

"distinguishes by sense [perception]"--to the flawed or "false" reason of the

pedantic curate, that starts with the "beyond" (97). - [TH]jowlerA common

name for a dog. - [TH]mM-- is Henry

More, a rationalist Cartesian theologian who argues that God orders the world

infallibly and always according to the best ends ("the best of all possible

worlds"). He wrote several books, including On the Immortality

of the Soul, where he sought to counter the Hobbesian view of life outside

of society as "nasty, brutish, and short" and instead to prove "the exsitence of

immaterial substance, or spirit, and therefore God" (Stanford Encyclopedia

of Philosophy); he is most well known for his idea of the Spirit of

Nature, which connected the material world to the spiritual. Like other Platonists

of the 17th century, he believed that the immortality of the soul proved an

afterlife, characterized by damnation or salvation. Rochester disagreed with this

perspective. - [TH]beastsIn the

following lines, Rochester sets up an extended comparison between the nature of

violence in the animal kingdom and in the human world. - [TH]square"To play

upon the square" means to play fairly (or "fair and square," in current colloquial

terms). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this expression was "[v]ery

common from c1670, frequently with reference to...gaming" ("square," adj.,

III.12.b). - [TH]dashesDuring this period, dashes were often used to

visibly omit a name that would identify the subject of satire. Usually,

contemporary readers would have understood who the author was referring to.natureIn Leviathan (1651), Hobbes argued that humans are completely

driven by the primary drives of appetite and aversion; people are selfish at their

root. In the state of nature, which is a state of war, “there is no place for

industry...; no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is

worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man

solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Paragraph 9, Chapter 13, Leviathan). - [TH]slavesRochester suggests that "the pretending part of the proud World" (175) use their

supposed spiritual superiority to weild tyrranical power over other people, not

recognizing that everyone is a "Slave." - [TH]courtCourt

here, as elsewhere, refers to the court of nobles and other people of power

surrounding King Charles II (or whomever was monarch at the time). Court culture,

in the Restoration, was often characterized both by stringent absolutism and a

permissiveness that distinguished those of privilege. To read more about

Restoration court culture, see Culture and Politics at the Court of Charles II,

1660-1685, by Matthew Jenkinson. - [TH]aurealReaders may

be more familiar with the noun form ("aura") of this obsolete adjective. "Aureal

Bribes" are bribes that are gilded or golden (OED). - [TH]bOther versions of Rochester's poem

replace the initial with "bishops."fourscoreA unit

of measurement, usually of time. A "score" is twenty; so, four score is four times

twenty, or eighty. - [TH]ifRochester here

makes an IF/THEN logical statement. If such "[in]conceiv[ably]" (218) "meek humble

M[e]n, of modest sense" (215) can be revealed, he'll "recant" (220) this poetic

statement. - [TH]rabble"Rabble" here is used as a

derogatory term to refer to the masses or the common people--and "their Laws"

(222)--from which mob Rochester distances himself through his libertinism. See the

OED "rabble," n.1 and adj., particularly sense 3.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

) - [JL]libertinismFor Margaret Ezell,

who writes about the performative quality of Restoration libertinism, Rochester's

libertinism was a deliberate assertion of privilege designed to cultivate power in

the court ("Enacting Libertinism: Court Performance and Literary Culture" in The Oxford English Literary History, Vol. V.). Rochester's

poem is a response to the question being asked here by a hypothetical clergyman

(the "formal band and beard"). Here, he is performing the persona of the pedantic,

prudish curate ultimately to mock him and his moral philosophy, thereby

cultivating a witty superiority.rageThe

clergyman describes Rochester's mind as "degen[e]rate," and his way of thinking,

deviant. Rochester’s poem is a “Satire against Reason and Mankind”; it is

fundamentally skeptical of the ability--or desirability--of reason and law to

ameliorate baser human interests. - [TH]speakerAt this point, Rochester's character speaks,

returning a satirical answer to the pedantic curate.Ignello

Nathaniel

Ingelo, born ca 1621. Graduate and fellow of the Queen’s College,

Cambridge. Ingelo was a clergyman and author of a religious romance entitled Bentivolio and Urania. Marianne Thormählen writes in aRochester: The Poems in Context that the works of Ingelo and Simon

Patrick mentioned below would have been well known during Rochester’s time. She

mentions that Rochester would have detested “Ingelo’s exalted view of man; and his

attacks on Epicurus and his followers”.pSimon Patrick, Bishop of Ely (1626-1707) was an English

theologian and, eventually, bishop; his book The Parable of

the Pilgrim (1663/4) is referenced here. Patrick's Pilgrim is an allegory along the same lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Patrick’s first assignment after

graduating from Queen's College, Cambridge, was as a domestic chaplain to Sir

Walter St. John, John Wilmot’s uncle (Dictionary of National Biography)> - [TH]sRichard Sibbes

(1577-1635), was a popular Puritan theologian, minister, and writer, in the

affective tradition with intellectual connections to Calvinism. He is most well

known for a work called The Bruised Reed, but Rochester

here references a work this editor has not been able to trace. Other editions of

the poem replace "replies" with "soliloquies," possibly suggesting a different

work, Richard Bayne's Holy Soliloquies (1637)--Sibbes wa

very influenced by Bayne. Regardless, all of these references are to popular

theologians during the 17th century. . He, too, studied at Cambridge, but his

Puritanism caused him to lose a lectureship there (Dictionary of National Biography). - [TH]bedlamBedlam is

the colloquial term for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, an asylum for the

mentally ill first established in 1676. It was often used as a broader term for

any location of perceived insanity. - [TH]sotA sot is a stupid

person, usually someone who is "stupified" with liquor or habitually drunk

(OED). - [TH]comparisonRochester compares the inflated ideology of the pedantic curate--whose "business"

is "Nonsense" and "impossibilities" (86)--with the superstitions that give witches

the power of flight. - [TH]powerRochester

refers here to reason as the falsely "exalted pow'r." The remainder of the poem

will lay out why the poet thinks so. - [TH]tubThe word tub has a lot of meanings during this period. Proverbially,

it is used to refer to a fiction, or a made-up story; but it also specifically

refers to the pulpit from which a non-conformist preacher spoke. Nonconformity

refers to any religious faith not strictly Anglican. It also has another meaning

that

Rochester would have known about--a "sweating-tub" or a sort of barrel

encasing the

body used specifically to treat venereal disease. See the

OED. - [TH]actionRochester became identified with philosophical and sexual libertinism of the

Restoration, which was characterized by the public, even performative pursuit of

pleasure and a vivid, almost nihilistic sexuality. Libertinism was underpinned by

a selective reading of Thomas Hobbes' theory of human nature. Hobbes, according to

Christopher Tilmouth, "declar[ed] that the passions, not reason, constituted the

proper, primary determinants of human conduct" and "posited...a new ideal of

happiness, equating felicity with a constant motion of the self from the

satisfaction of one appetite to the next, and he accorded fear and the lust for

power critical roles in this kinetic process" (Tilmouth 4-5).

Hobbes

characterized humankind in nature as in a permanent state of conflict and

struggle, governed by their appetites and their passions, and to avoid this

chaotic, violent state of nature, human societies contract with strong leaders to

bring order to passion and law to desire: "it is manifest that, during the time

men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that

condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every

man" (Leviathan, XIII, para. 8). Rochester positions his

libertinism as a moral freedom beyond the civil codes of contractual law. For more

on Restoration libertinism, see James Turner, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London, especially

chapter 6; and Diane Maybank'sarticle for the British Library about libertinism on the

Restoration stage. - [TH]reasonsRochester compares his materialist sense of reason--reason that rightly

"distinguishes by sense [perception]"--to the flawed or "false" reason of the

pedantic curate, that starts with the "beyond" (97). - [TH]jowlerA common

name for a dog. - [TH]mM-- is Henry

More, a rationalist Cartesian theologian who argues that God orders the world

infallibly and always according to the best ends ("the best of all possible

worlds"). He wrote several books, including On the Immortality

of the Soul, where he sought to counter the Hobbesian view of life outside

of society as "nasty, brutish, and short" and instead to prove "the exsitence of

immaterial substance, or spirit, and therefore God" (Stanford Encyclopedia

of Philosophy); he is most well known for his idea of the Spirit of

Nature, which connected the material world to the spiritual. Like other Platonists

of the 17th century, he believed that the immortality of the soul proved an

afterlife, characterized by damnation or salvation. Rochester disagreed with this

perspective. - [TH]beastsIn the

following lines, Rochester sets up an extended comparison between the nature of

violence in the animal kingdom and in the human world. - [TH]square"To play

upon the square" means to play fairly (or "fair and square," in current colloquial

terms). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this expression was "[v]ery

common from c1670, frequently with reference to...gaming" ("square," adj.,

III.12.b). - [TH]dashesDuring this period, dashes were often used to

visibly omit a name that would identify the subject of satire. Usually,

contemporary readers would have understood who the author was referring to.natureIn Leviathan (1651), Hobbes argued that humans are completely

driven by the primary drives of appetite and aversion; people are selfish at their

root. In the state of nature, which is a state of war, “there is no place for

industry...; no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is

worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man

solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Paragraph 9, Chapter 13, Leviathan). - [TH]slavesRochester suggests that "the pretending part of the proud World" (175) use their

supposed spiritual superiority to weild tyrranical power over other people, not

recognizing that everyone is a "Slave." - [TH]courtCourt

here, as elsewhere, refers to the court of nobles and other people of power

surrounding King Charles II (or whomever was monarch at the time). Court culture,

in the Restoration, was often characterized both by stringent absolutism and a

permissiveness that distinguished those of privilege. To read more about

Restoration court culture, see Culture and Politics at the Court of Charles II,

1660-1685, by Matthew Jenkinson. - [TH]aurealReaders may

be more familiar with the noun form ("aura") of this obsolete adjective. "Aureal

Bribes" are bribes that are gilded or golden (OED). - [TH]bOther versions of Rochester's poem

replace the initial with "bishops."fourscoreA unit

of measurement, usually of time. A "score" is twenty; so, four score is four times

twenty, or eighty. - [TH]ifRochester here

makes an IF/THEN logical statement. If such "[in]conceiv[ably]" (218) "meek humble

M[e]n, of modest sense" (215) can be revealed, he'll "recant" (220) this poetic

statement. - [TH]rabble"Rabble" here is used as a

derogatory term to refer to the masses or the common people--and "their Laws"

(222)--from which mob Rochester distances himself through his libertinism. See the

OED "rabble," n.1 and adj., particularly sense 3.[TP]

POEMS

ON SEVERAL

OCCASIONS

Printed at ANTWERP,Antwerp Antwerp 'Antwerp’ is a false imprint. James Thorpe discusses this interesting detail in The Earliest Editions of Rochester’s Poems" noting that the printings were “unlicensed books printed in London” where the false imprint was used for “simple subterfuge presumably intended to attract the lovers of racy literature or distract prosecution”. - [JL] 1690.

ON SEVERAL

OCCASIONS

Printed at ANTWERP,Antwerp Antwerp 'Antwerp’ is a false imprint. James Thorpe discusses this interesting detail in The Earliest Editions of Rochester’s Poems" noting that the printings were “unlicensed books printed in London” where the false imprint was used for “simple subterfuge presumably intended to attract the lovers of racy literature or distract prosecution”. - [JL] 1690.

Footnotes

author_ John Wilmot,

second earl of Rochester, was born to Anne St. John, Countess of Rochester and

Henry Wilmot, first earl of Rochester on April 1st, 1647, in Oxfordshire,

England. In 1658, at age eleven, John Wilmot succeeded his fathers’ Earldom.

Just three years later, Wilmot received an M.A. from Wadham College, Oxford.

Charles II, King of Great Britain and Ireland at the time, appointed Rochester

a tutor to be mentored by. Rochester and his tutor, Sir Andrew Balfour

travelled through France and Italy until 1664 when Rochester returned to

Charles’ court. In his time at court, Wilmot became one of the most famous

poets and controversial satirists of the Restoration period. In the collection

The Poems of John Wilmot, editor Keith Walker notes

that Rochester’s raucous lifestyle and many vices--some characteristics of his

libertinism--often garnered contempt from the king’s court. Though he was a

notable poet, Rochester acted as a patron to many playwrights including John

Dryden and John Fletcher. The latter part of the 1670s saw Rochester contribute

more seriously to the affairs of the state. On his deathbed, Rochester is said

to have called upon his close friend, the bishop of Salisbury, Gilbert Burnet,

to recant his past libertinism and convert to Christianity. Rochester died on

July 26th, 1680, in Oxfordshire, at the age of thirty-three. The image included

here (NPG 804), licensed under Creative Commons, is a portrait in oil on canvas

of John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester by an unknown artist (c.1665-1670), via

the National Portrait Gallery, UK. As the notes to the portrait point out, "This portrait has a

satirical message almost certainly of Rochester's devising. It portrays him,

manuscript in hand, bestowing the poet's laurels on a jabbering monkey who is

tearing out the pages of a book and handing them crumpled to the

poet."

John Wilmot,

second earl of Rochester, was born to Anne St. John, Countess of Rochester and

Henry Wilmot, first earl of Rochester on April 1st, 1647, in Oxfordshire,

England. In 1658, at age eleven, John Wilmot succeeded his fathers’ Earldom.

Just three years later, Wilmot received an M.A. from Wadham College, Oxford.

Charles II, King of Great Britain and Ireland at the time, appointed Rochester

a tutor to be mentored by. Rochester and his tutor, Sir Andrew Balfour

travelled through France and Italy until 1664 when Rochester returned to

Charles’ court. In his time at court, Wilmot became one of the most famous

poets and controversial satirists of the Restoration period. In the collection

The Poems of John Wilmot, editor Keith Walker notes

that Rochester’s raucous lifestyle and many vices--some characteristics of his

libertinism--often garnered contempt from the king’s court. Though he was a

notable poet, Rochester acted as a patron to many playwrights including John

Dryden and John Fletcher. The latter part of the 1670s saw Rochester contribute

more seriously to the affairs of the state. On his deathbed, Rochester is said

to have called upon his close friend, the bishop of Salisbury, Gilbert Burnet,

to recant his past libertinism and convert to Christianity. Rochester died on

July 26th, 1680, in Oxfordshire, at the age of thirty-three. The image included

here (NPG 804), licensed under Creative Commons, is a portrait in oil on canvas

of John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester by an unknown artist (c.1665-1670), via

the National Portrait Gallery, UK. As the notes to the portrait point out, "This portrait has a

satirical message almost certainly of Rochester's devising. It portrays him,

manuscript in hand, bestowing the poet's laurels on a jabbering monkey who is

tearing out the pages of a book and handing them crumpled to the

poet."

John Wilmot,

second earl of Rochester, was born to Anne St. John, Countess of Rochester and

Henry Wilmot, first earl of Rochester on April 1st, 1647, in Oxfordshire,

England. In 1658, at age eleven, John Wilmot succeeded his fathers’ Earldom.

Just three years later, Wilmot received an M.A. from Wadham College, Oxford.

Charles II, King of Great Britain and Ireland at the time, appointed Rochester

a tutor to be mentored by. Rochester and his tutor, Sir Andrew Balfour

travelled through France and Italy until 1664 when Rochester returned to

Charles’ court. In his time at court, Wilmot became one of the most famous

poets and controversial satirists of the Restoration period. In the collection

The Poems of John Wilmot, editor Keith Walker notes

that Rochester’s raucous lifestyle and many vices--some characteristics of his

libertinism--often garnered contempt from the king’s court. Though he was a

notable poet, Rochester acted as a patron to many playwrights including John

Dryden and John Fletcher. The latter part of the 1670s saw Rochester contribute

more seriously to the affairs of the state. On his deathbed, Rochester is said

to have called upon his close friend, the bishop of Salisbury, Gilbert Burnet,

to recant his past libertinism and convert to Christianity. Rochester died on

July 26th, 1680, in Oxfordshire, at the age of thirty-three. The image included

here (NPG 804), licensed under Creative Commons, is a portrait in oil on canvas

of John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester by an unknown artist (c.1665-1670), via

the National Portrait Gallery, UK. As the notes to the portrait point out, "This portrait has a

satirical message almost certainly of Rochester's devising. It portrays him,

manuscript in hand, bestowing the poet's laurels on a jabbering monkey who is

tearing out the pages of a book and handing them crumpled to the

poet."

John Wilmot,

second earl of Rochester, was born to Anne St. John, Countess of Rochester and

Henry Wilmot, first earl of Rochester on April 1st, 1647, in Oxfordshire,

England. In 1658, at age eleven, John Wilmot succeeded his fathers’ Earldom.

Just three years later, Wilmot received an M.A. from Wadham College, Oxford.

Charles II, King of Great Britain and Ireland at the time, appointed Rochester

a tutor to be mentored by. Rochester and his tutor, Sir Andrew Balfour

travelled through France and Italy until 1664 when Rochester returned to

Charles’ court. In his time at court, Wilmot became one of the most famous

poets and controversial satirists of the Restoration period. In the collection

The Poems of John Wilmot, editor Keith Walker notes

that Rochester’s raucous lifestyle and many vices--some characteristics of his

libertinism--often garnered contempt from the king’s court. Though he was a

notable poet, Rochester acted as a patron to many playwrights including John

Dryden and John Fletcher. The latter part of the 1670s saw Rochester contribute

more seriously to the affairs of the state. On his deathbed, Rochester is said

to have called upon his close friend, the bishop of Salisbury, Gilbert Burnet,

to recant his past libertinism and convert to Christianity. Rochester died on

July 26th, 1680, in Oxfordshire, at the age of thirty-three. The image included

here (NPG 804), licensed under Creative Commons, is a portrait in oil on canvas

of John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester by an unknown artist (c.1665-1670), via

the National Portrait Gallery, UK. As the notes to the portrait point out, "This portrait has a

satirical message almost certainly of Rochester's devising. It portrays him,

manuscript in hand, bestowing the poet's laurels on a jabbering monkey who is

tearing out the pages of a book and handing them crumpled to the

poet."Antwerp_

'Antwerp’ is a false imprint. James Thorpe discusses this interesting detail in

The Earliest Editions of

Rochester’s Poems" noting that the printings were “unlicensed books

printed in London” where the false imprint was used for “simple subterfuge

presumably intended to attract the lovers of racy literature or distract

prosecution”.

gross_In

this sense, gross refers to materiality as distinct from ethereality or

spirituality. See OED adj III.8.c: describes "things material or perceptible to

the senses, as contrasted with what is spiritual, ethereal, or impalpable."

ignus-fatuus_From the Latin meaning, literally, "foolish fire," an

ignis fatuus is a will-o'the-wisp, a flitting phosphorescent light that led

travelers astray in marshy areas like the "Fenny Bogs and Thorny Brakes" (15)

Rochester describes below (OED, "ignis fatuus,

n.").

wrong_Lines

29-36 explain how, from Rochester's perspective, this approach to life that prizes

reason is "in the wrong."

reason_The

"reasoning Enging" is the mind--here, Rochester notes that the mind is "huddled in

[the] dirt" of the physical body. The body and the mind are intertwined, rather

than separate.

bubbles_Here used

as a noun, "bubbles" in this sense refers to those who have been fooled or cheated

(OED, n.2b).

wits_ During the Restoration period in England, Charles II

would often be found in the company of young intellectuals or "wits." In The Court Wits of the Restoration, John Harold Wilson

writes that “the label Wit was attached only to one who made some real pretense

to distinction as a poet, critic, translator, raconteur, or a man of learning"

(6). Among the so-called "court wits" were Rochester, Sir John

Suckling, Edmund Waller, and others. [add paraphrase from page 5 of Tilmouth:

https://books.google.com/books?id=DipmhwkFfQMC

pleasure_As

Jeremy Webster argues in Performing Libertinism in Charles II’s

Court, “[l]ibertines...performed traditionally secretive acts— excessive

drinking, carnality, sodomy, sedition, assault, and sacrilege—in the public sphere

in a variety of ways” (2). Here, Rochester is talking in part about sexual

pleasure that, once enjoyed, brings causes the enjoyer to fear or hate that

pleasure. This fear is in part existential or philosophical--pleasure brings with

it "dang'rous" (41) questions about the value of social order founded on

reason--but it is also material, as in the fear of sexually transmitted infection,

from which Rochester sufferred. The "succeeding pains" (40) to which he refers

encapsulate both kinds of fears.

fops_In "Fops and Some Versions of Foppery,"

Robert B. Heilman discusses this term, noting that as a “general, all-purpose

carrier of disapproval, fop works much like fool" (364).

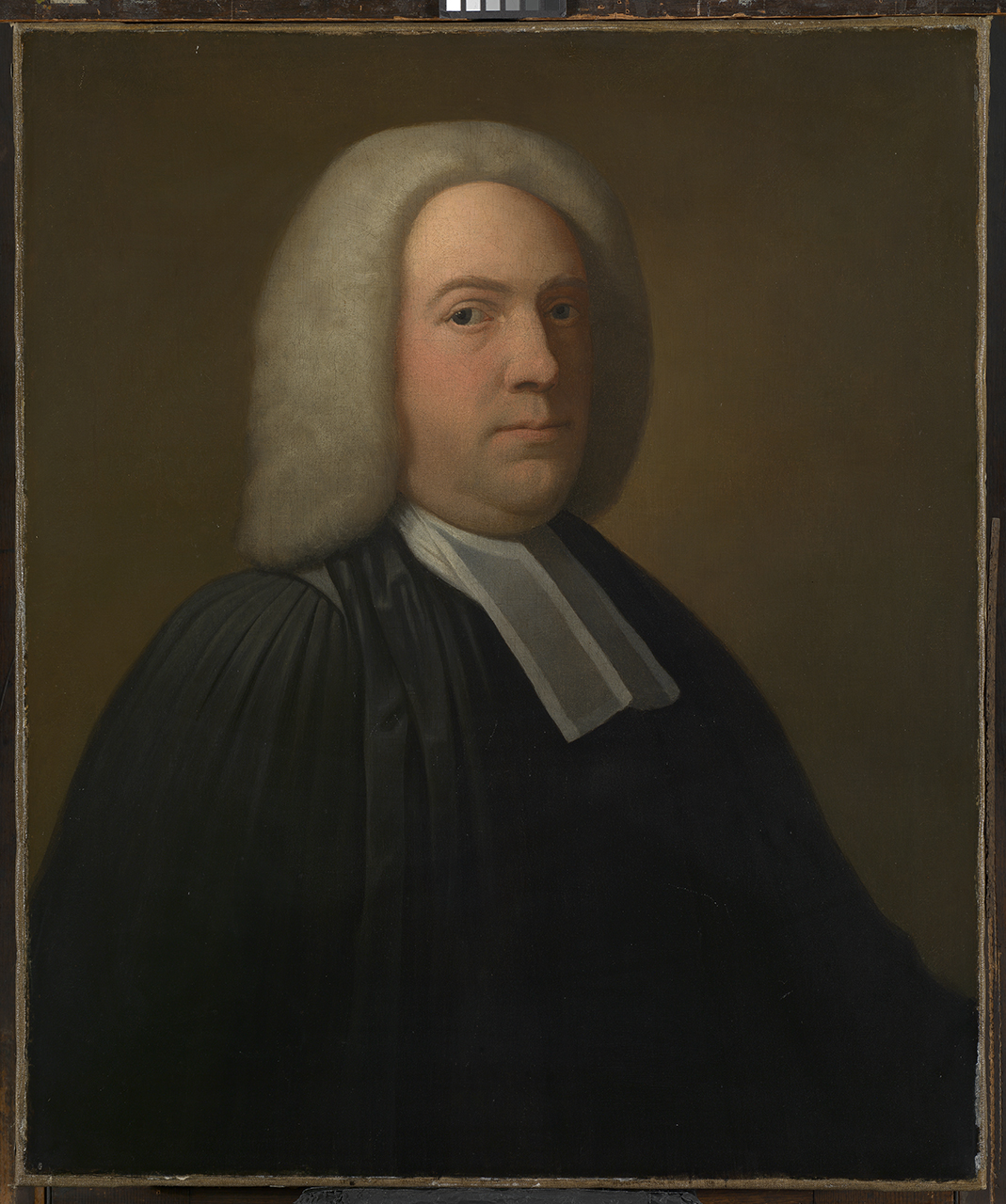

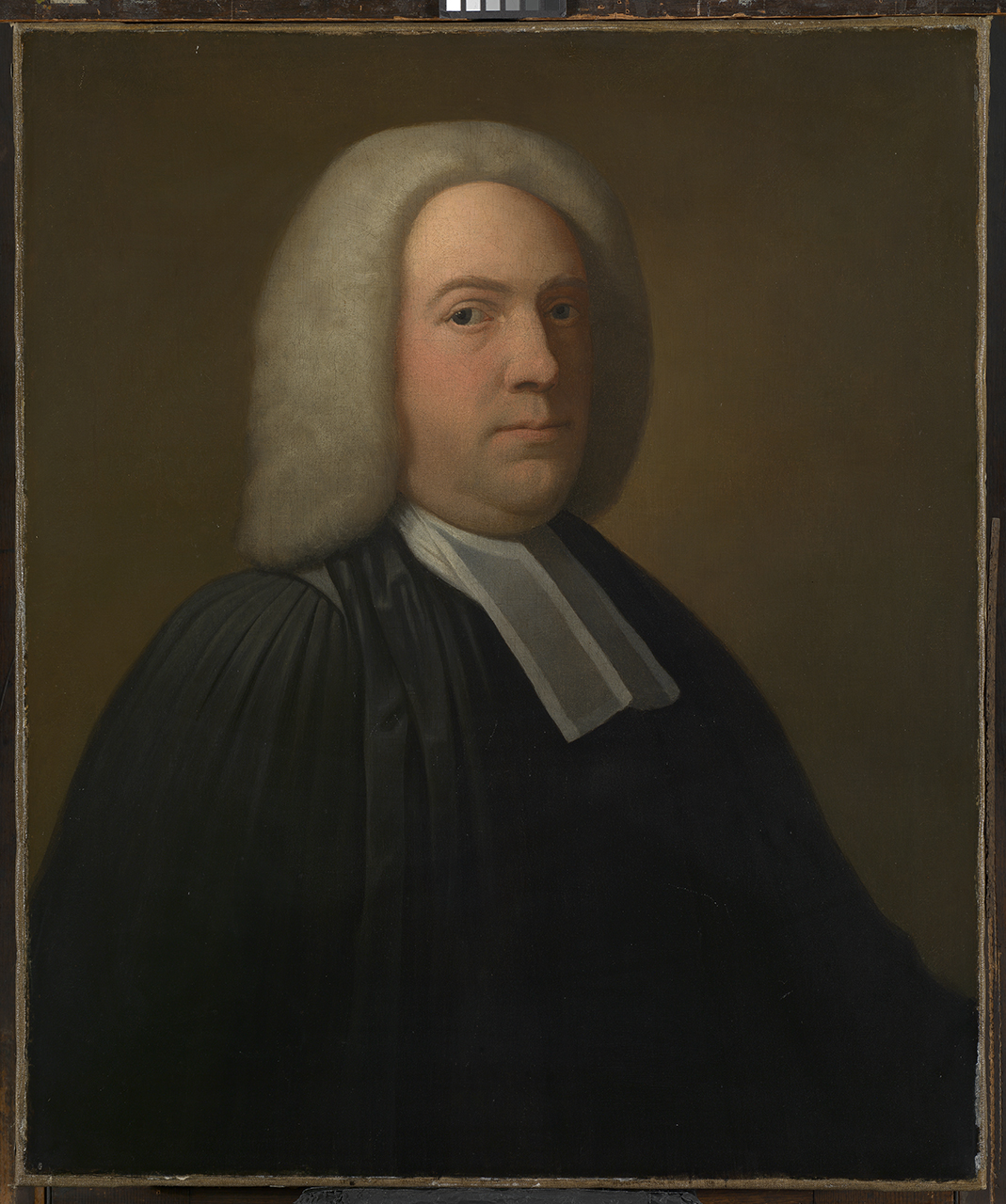

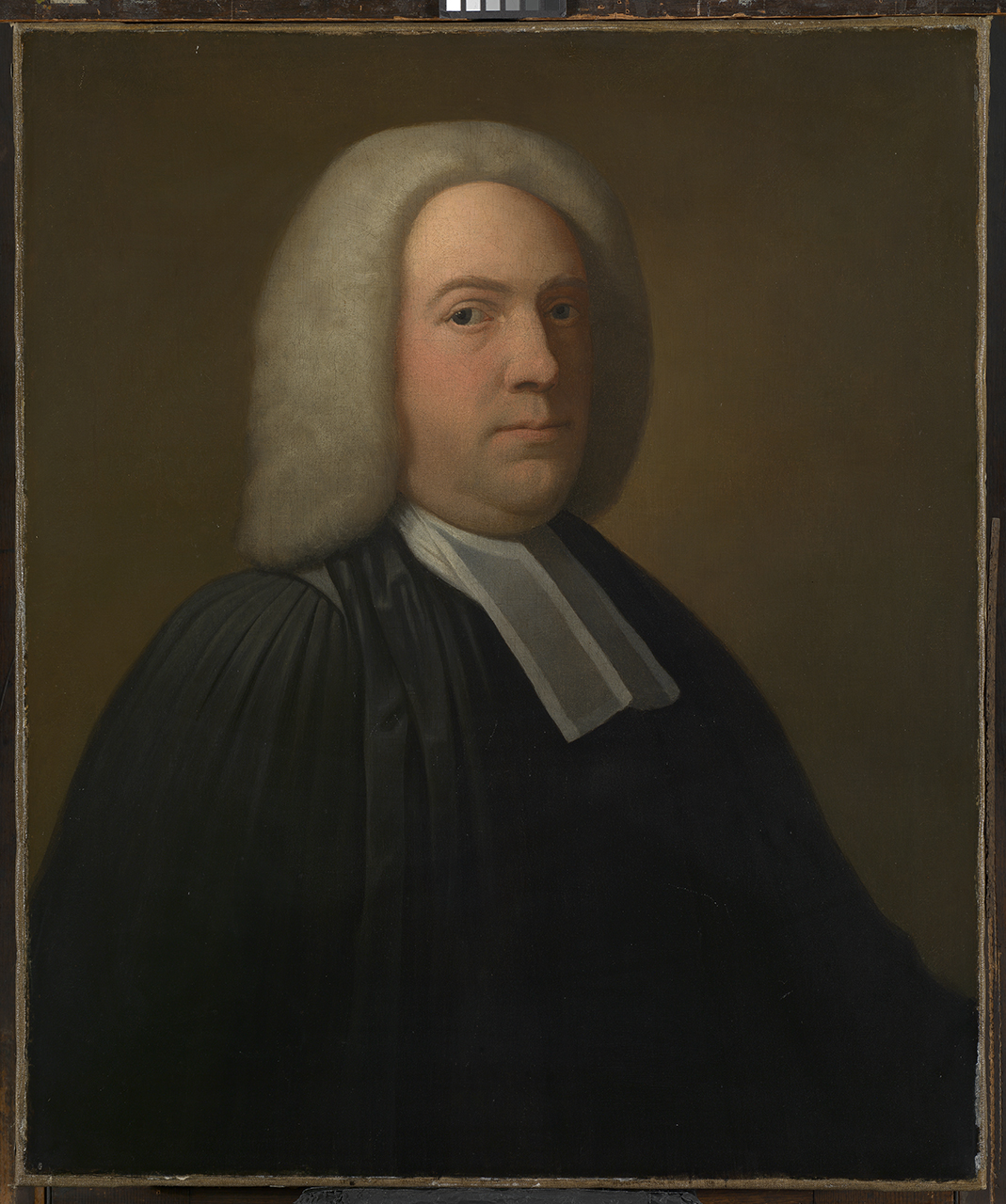

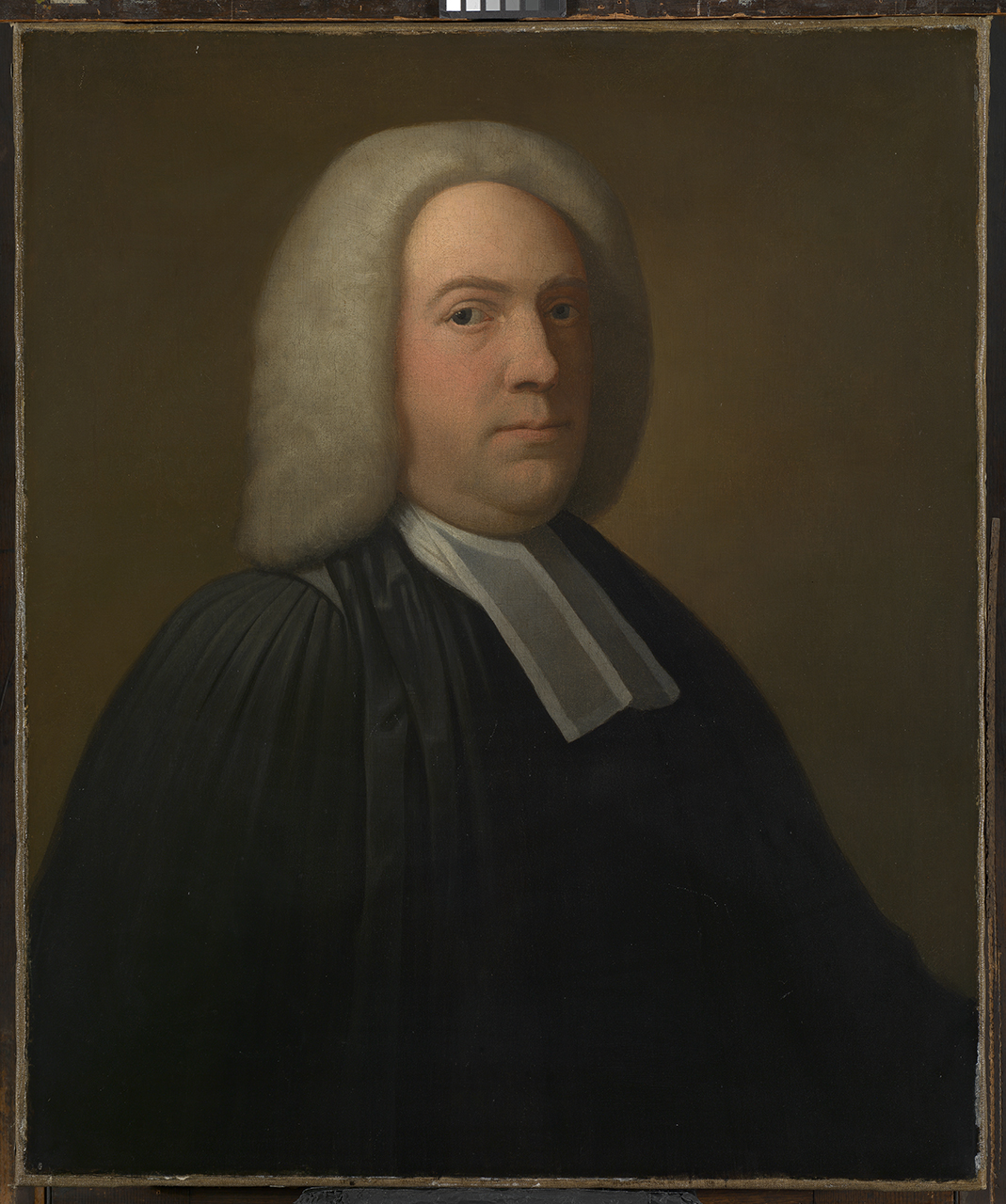

band_ According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

)

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

)

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

)

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "band" refers to an

eighteenth-century neck piece traditionally worn by clergy members, scholars,

and those in the legal profession (n.2.4b). In this portrait

by Benjamin Wilson (c.1750) of James Bradley, third Astronomer Royal from 1742

to 1762, the band at his neck indicates his academic profession. Via the

Royal Museums Greenwich online collections, this Wilson's portrait of

Bradley is housed in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

)libertinism_For Margaret Ezell,

who writes about the performative quality of Restoration libertinism, Rochester's

libertinism was a deliberate assertion of privilege designed to cultivate power in

the court ("Enacting Libertinism: Court Performance and Literary Culture" in The Oxford English Literary History, Vol. V.). Rochester's

poem is a response to the question being asked here by a hypothetical clergyman

(the "formal band and beard"). Here, he is performing the persona of the pedantic,

prudish curate ultimately to mock him and his moral philosophy, thereby

cultivating a witty superiority.

rage_The

clergyman describes Rochester's mind as "degen[e]rate," and his way of thinking,

deviant. Rochester’s poem is a “Satire against Reason and Mankind”; it is

fundamentally skeptical of the ability--or desirability--of reason and law to

ameliorate baser human interests.

p_Simon Patrick, Bishop of Ely (1626-1707) was an English

theologian and, eventually, bishop; his book The Parable of

the Pilgrim (1663/4) is referenced here. Patrick's Pilgrim is an allegory along the same lines of John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Patrick’s first assignment after

graduating from Queen's College, Cambridge, was as a domestic chaplain to Sir

Walter St. John, John Wilmot’s uncle (Dictionary of National Biography)>

s_Richard Sibbes

(1577-1635), was a popular Puritan theologian, minister, and writer, in the

affective tradition with intellectual connections to Calvinism. He is most well

known for a work called The Bruised Reed, but Rochester

here references a work this editor has not been able to trace. Other editions of

the poem replace "replies" with "soliloquies," possibly suggesting a different

work, Richard Bayne's Holy Soliloquies (1637)--Sibbes wa

very influenced by Bayne. Regardless, all of these references are to popular

theologians during the 17th century. . He, too, studied at Cambridge, but his

Puritanism caused him to lose a lectureship there (Dictionary of National Biography).

bedlam_Bedlam is

the colloquial term for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, an asylum for the

mentally ill first established in 1676. It was often used as a broader term for

any location of perceived insanity.

sot_A sot is a stupid

person, usually someone who is "stupified" with liquor or habitually drunk

(OED).

comparison_Rochester compares the inflated ideology of the pedantic curate--whose "business"

is "Nonsense" and "impossibilities" (86)--with the superstitions that give witches

the power of flight.

power_Rochester

refers here to reason as the falsely "exalted pow'r." The remainder of the poem

will lay out why the poet thinks so.

tub_The word tub has a lot of meanings during this period. Proverbially,

it is used to refer to a fiction, or a made-up story; but it also specifically

refers to the pulpit from which a non-conformist preacher spoke. Nonconformity

refers to any religious faith not strictly Anglican. It also has another meaning

that

Rochester would have known about--a "sweating-tub" or a sort of barrel

encasing the

body used specifically to treat venereal disease. See the

OED.

action_Rochester became identified with philosophical and sexual libertinism of the

Restoration, which was characterized by the public, even performative pursuit of

pleasure and a vivid, almost nihilistic sexuality. Libertinism was underpinned by

a selective reading of Thomas Hobbes' theory of human nature. Hobbes, according to

Christopher Tilmouth, "declar[ed] that the passions, not reason, constituted the

proper, primary determinants of human conduct" and "posited...a new ideal of

happiness, equating felicity with a constant motion of the self from the

satisfaction of one appetite to the next, and he accorded fear and the lust for

power critical roles in this kinetic process" (Tilmouth 4-5).

Hobbes

characterized humankind in nature as in a permanent state of conflict and

struggle, governed by their appetites and their passions, and to avoid this

chaotic, violent state of nature, human societies contract with strong leaders to

bring order to passion and law to desire: "it is manifest that, during the time

men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that

condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every

man" (Leviathan, XIII, para. 8). Rochester positions his

libertinism as a moral freedom beyond the civil codes of contractual law. For more

on Restoration libertinism, see James Turner, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London, especially

chapter 6; and Diane Maybank'sarticle for the British Library about libertinism on the

Restoration stage.

reasons_Rochester compares his materialist sense of reason--reason that rightly

"distinguishes by sense [perception]"--to the flawed or "false" reason of the

pedantic curate, that starts with the "beyond" (97).