Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus

By

Mary Shelley

Transcription, correction, editorial commentary, and markup by Students and Staff of Marymount University, Ally Freeland, Amy Ridderhof, Sabrina Koumoin, Ashley Swann, Tonya Howe

prometheus

Source: Prometheus Attacked by an Eagle (c.1750), attributed to René-Michel Slodtz, from the Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne.

Prometheus is a Greek trickster Titan known as "Forethought". In one

myth, Prometheus created man, but in the more common myth, Prometheus protected

man by tricking Zeus out of a prize sacrifice of meat and giving it to humans.

Zeus then prevented humans from accessing fire, which Prometheus gave to humans

by hiding it inside a fennel-stalk. This slight against Zeus caused Zeus the

Olympian to punish Prometheus dearly; in one instance he is tied to a rock and

his liver is continually eaten and replenished every day.

While Frankenstein was being published, Percy Shelley,

Mary Shelley’s husband, wrote a closet drama about the myth entitled Prometheus Unbound which can be read at

Poetry Foundation. In Shelley’s poem Zeus falls from power, allowing

Prometheus to escape his fetters. This poem is a response to Aeschylus’ drama Prometheus Bound, one of the

first classical tragedies that pits Zeus’ power against Prometheus’ ego. A full-text

version of the Aeschelus play is available at the Internet Classics

Archive. Victor Frankenstein--the "modern Prometheus"--is more akin to

the Prometheus of Aeschylus’ drama, a creator who finds his creation

"wretched." Frankenstein is very different from the Hesiodic understanding of

Prometheus, which,

as Norman Austin notes in Meaning and Being in

Myth, saw him as a benefactor and caretaker, not a creator who

abandoned his creation (77).

- [AF]epigraph

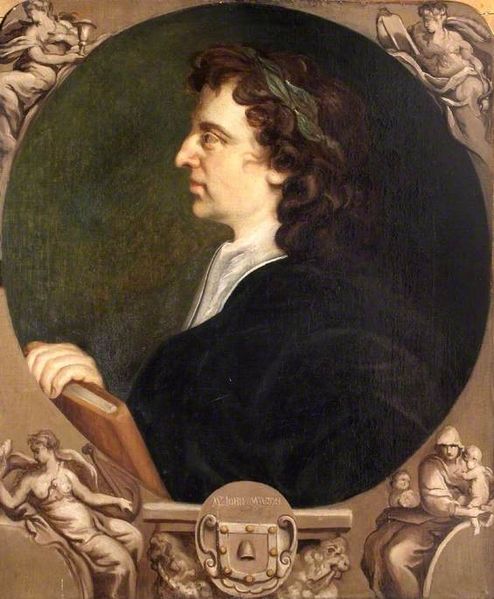

This epigraph quotes

Paradise Lost (X.743-745), where Adam

laments his expulsion from Eden. Milton’s epic poem is one of many texts

that had a profound effect on Mary Shelley. Its influence can be seen

throughout the novel, particularly in relation to the creature’s

self-education, and it is one of the books that he finds and reads while he

is living near the De Lacey’s cottage (Volume II, Chapter 7). When the

creature confronts Victor Frankenstein, his "Maker," he compares himself to

Adam (Volume II, Chapter 2). For more information about the influence of Paradise Lost in Frankenstein,

see John Lamb’s "Mary

Shelley's Frankenstein and Milton's Monstrous Myth" and the

overview of Paradise Lostin the "Romantics and

Victorians" exhibit at the British Library.

Source: Prometheus Attacked by an Eagle (c.1750), attributed to René-Michel Slodtz, from the Baillieu Library Print Collection, University of Melbourne.

Prometheus is a Greek trickster Titan known as "Forethought". In one

myth, Prometheus created man, but in the more common myth, Prometheus protected

man by tricking Zeus out of a prize sacrifice of meat and giving it to humans.

Zeus then prevented humans from accessing fire, which Prometheus gave to humans

by hiding it inside a fennel-stalk. This slight against Zeus caused Zeus the

Olympian to punish Prometheus dearly; in one instance he is tied to a rock and

his liver is continually eaten and replenished every day.

While Frankenstein was being published, Percy Shelley,

Mary Shelley’s husband, wrote a closet drama about the myth entitled Prometheus Unbound which can be read at

Poetry Foundation. In Shelley’s poem Zeus falls from power, allowing

Prometheus to escape his fetters. This poem is a response to Aeschylus’ drama Prometheus Bound, one of the

first classical tragedies that pits Zeus’ power against Prometheus’ ego. A full-text

version of the Aeschelus play is available at the Internet Classics

Archive. Victor Frankenstein--the "modern Prometheus"--is more akin to

the Prometheus of Aeschylus’ drama, a creator who finds his creation

"wretched." Frankenstein is very different from the Hesiodic understanding of

Prometheus, which,

as Norman Austin notes in Meaning and Being in

Myth, saw him as a benefactor and caretaker, not a creator who

abandoned his creation (77).

- [AF]epigraph

This epigraph quotes

Paradise Lost (X.743-745), where Adam

laments his expulsion from Eden. Milton’s epic poem is one of many texts

that had a profound effect on Mary Shelley. Its influence can be seen

throughout the novel, particularly in relation to the creature’s

self-education, and it is one of the books that he finds and reads while he

is living near the De Lacey’s cottage (Volume II, Chapter 7). When the

creature confronts Victor Frankenstein, his "Maker," he compares himself to

Adam (Volume II, Chapter 2). For more information about the influence of Paradise Lost in Frankenstein,

see John Lamb’s "Mary

Shelley's Frankenstein and Milton's Monstrous Myth" and the

overview of Paradise Lostin the "Romantics and

Victorians" exhibit at the British Library.

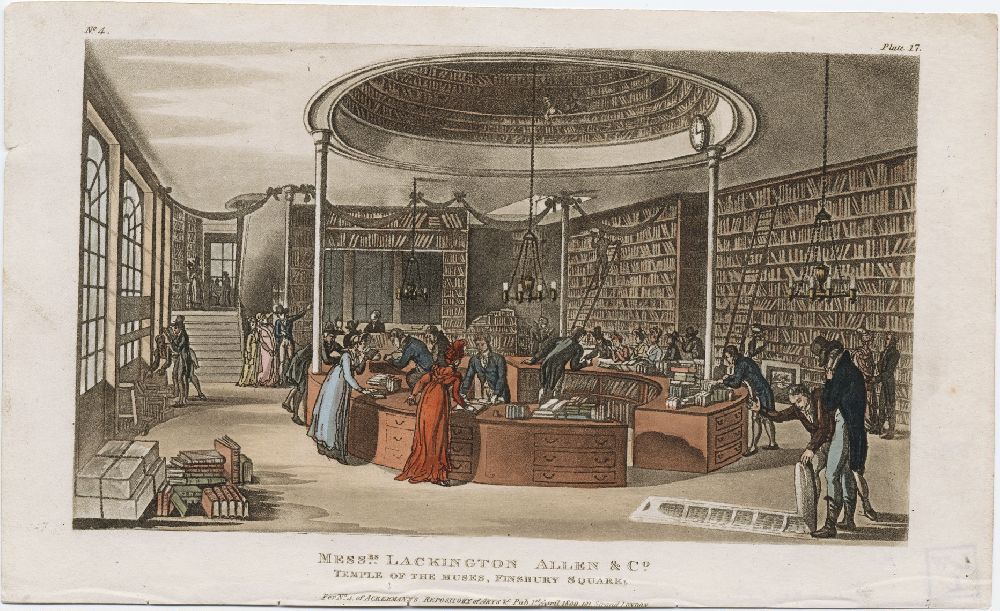

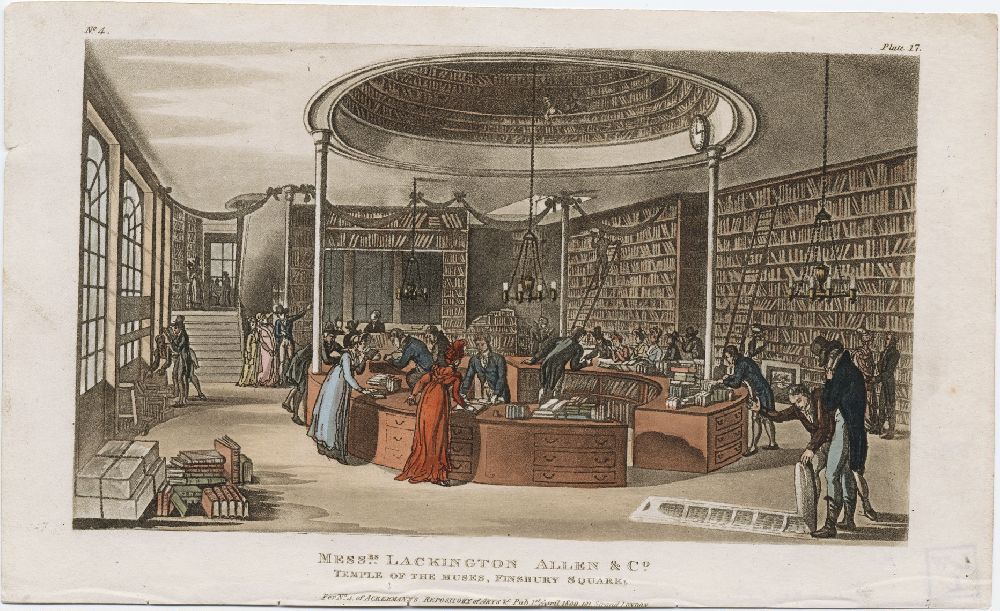

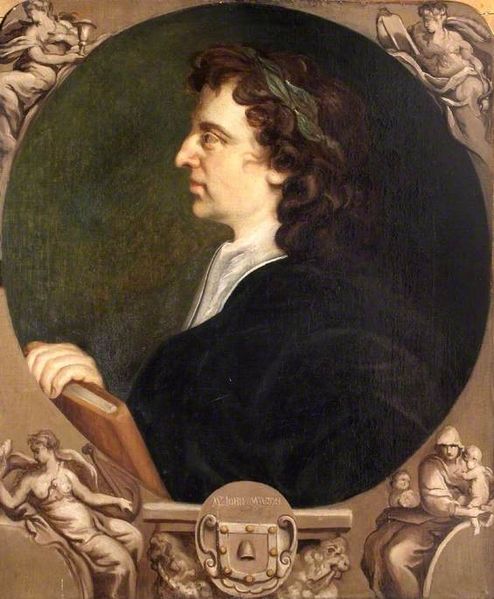

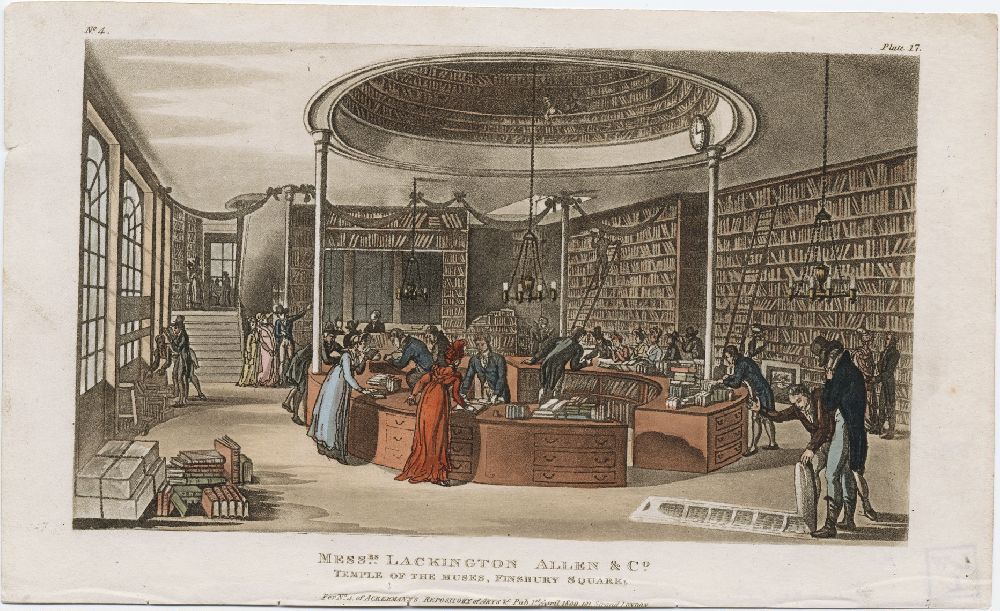

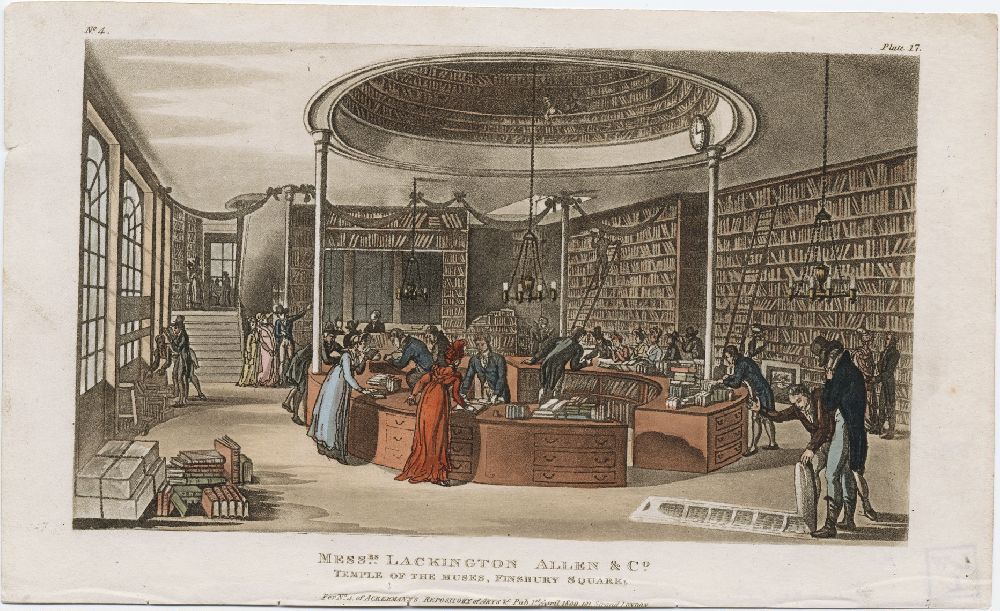

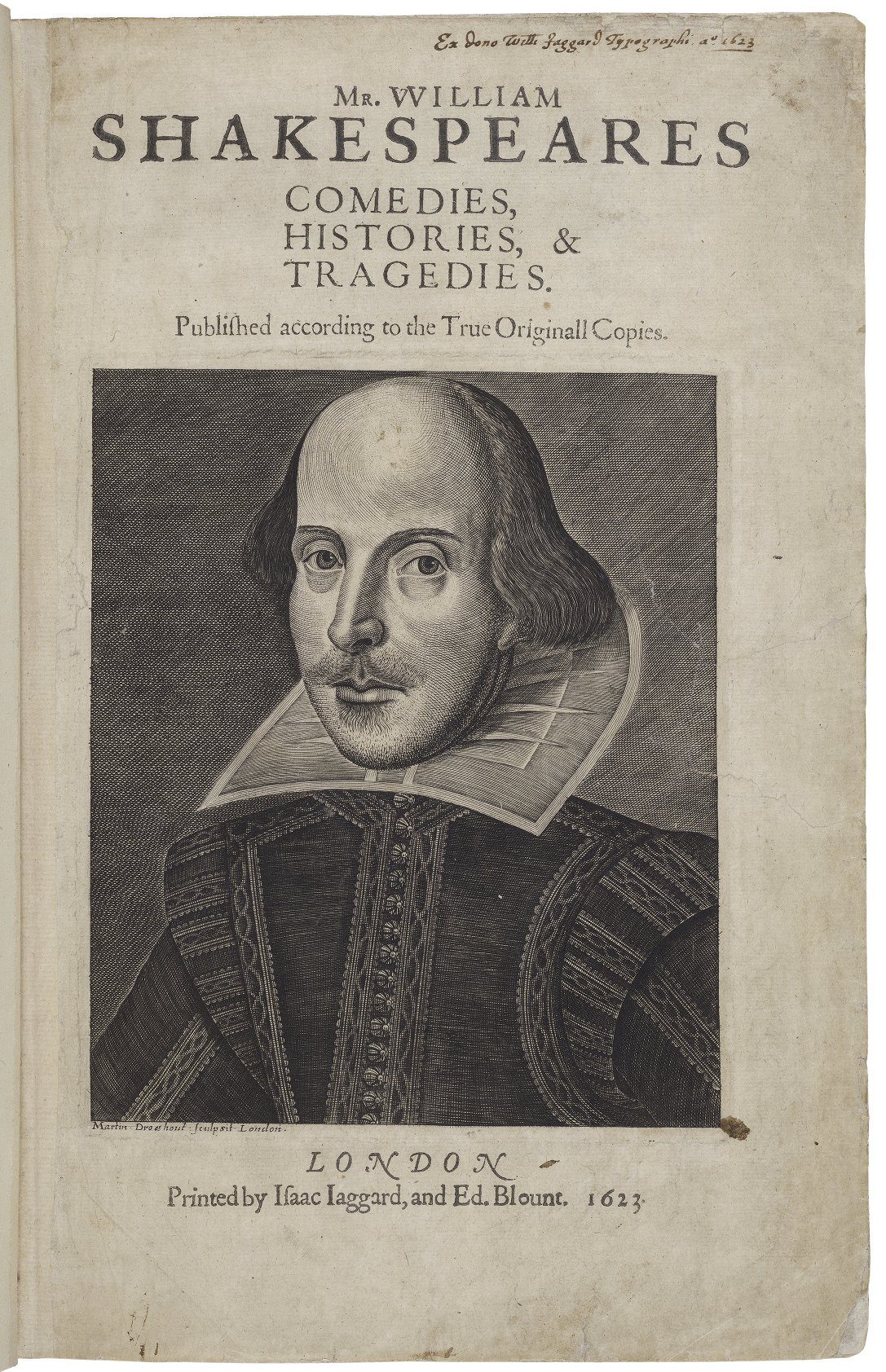

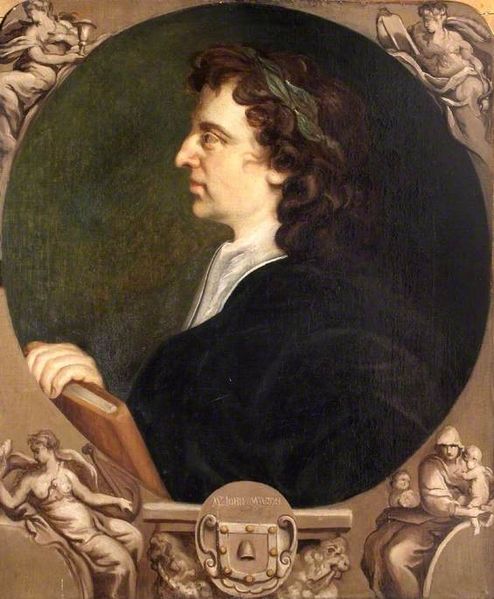

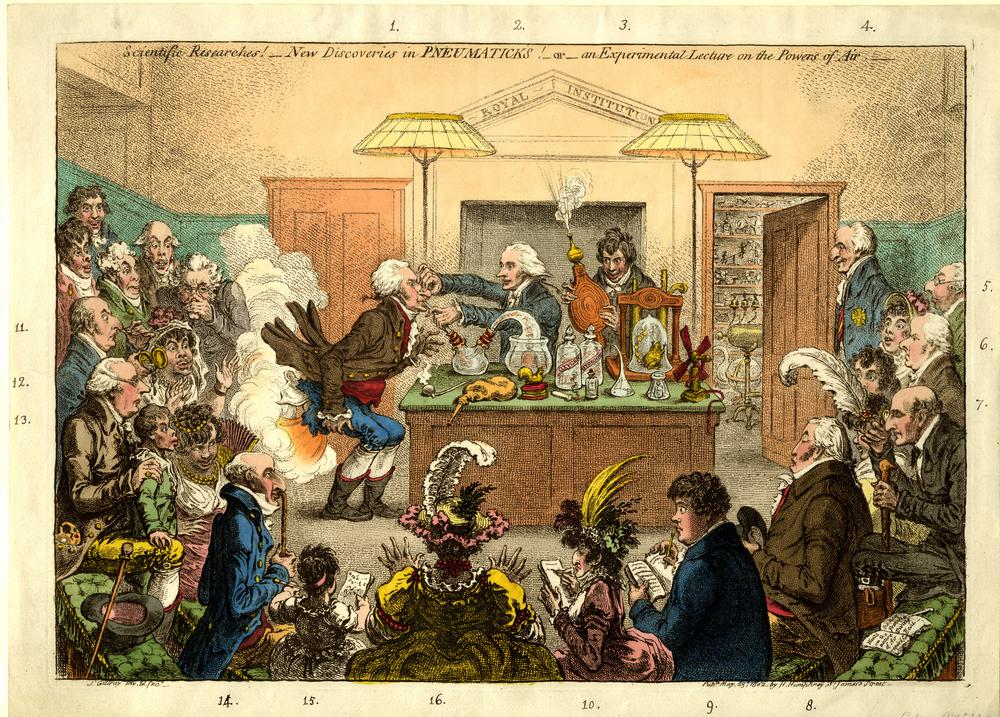

- [AF]paradise_lost John Milton (1608-1674) was an English poet most notably known for Paradise Lost, a twelve-volume epic poem in blank verse about the fall of man. Milton’s poem is an important intertext--even, as BBC Britain’s Benjamin Ramm notes, the inspiration, for Shelley. The Romantics placed importance in feeling and nature, and Milton epitomized that throughout his poem, showing the the evolution of human consciousness and the building up of the human spirit. The independence and individuality he gives to Satan creates sympathy for a hated stock character, redeeming him in the reader’s eyes. This in turn projects the idea of redemption of the spirit through internal means, removing the need for deliverance through an omnipotent being. See more in The Oxford Handbook of Milton by Nicholas McDowell. At the beginning of Paradise Lost, Milton states that the purpose of the poem is to "justifie the wayes of God to men" (I.26). This idea speaks to Shelley’s themes of free will and theodicy. The story of Paradise Lost is felt acutely by Victor Frankenstein and his Creature, and many allusions to it appear throughout the text. An interesting juxtaposition of religious thought to her scientific filled novel, Mary Shelley combines the contemporary understanding of science with an obvious allusion to the religious folly and fall of man. For more information about the influence of Paradise Lost in Frankenstein, see Burton Pollin’s Philosophical and Literary Sources of Frankenstein, John Lamb’s "Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and Milton's Monstrous Myth", and the overview of Paradise Lostin the "Romantics and Victorians" exhibit at the British Library. - [AF]publisher Source: Messrs. Lackington Allen & Co. Temple of the Muses, Finsbury Square (1809), etching by Rudolph Ackerman, via the Lewis Walpole Library of Yale University.

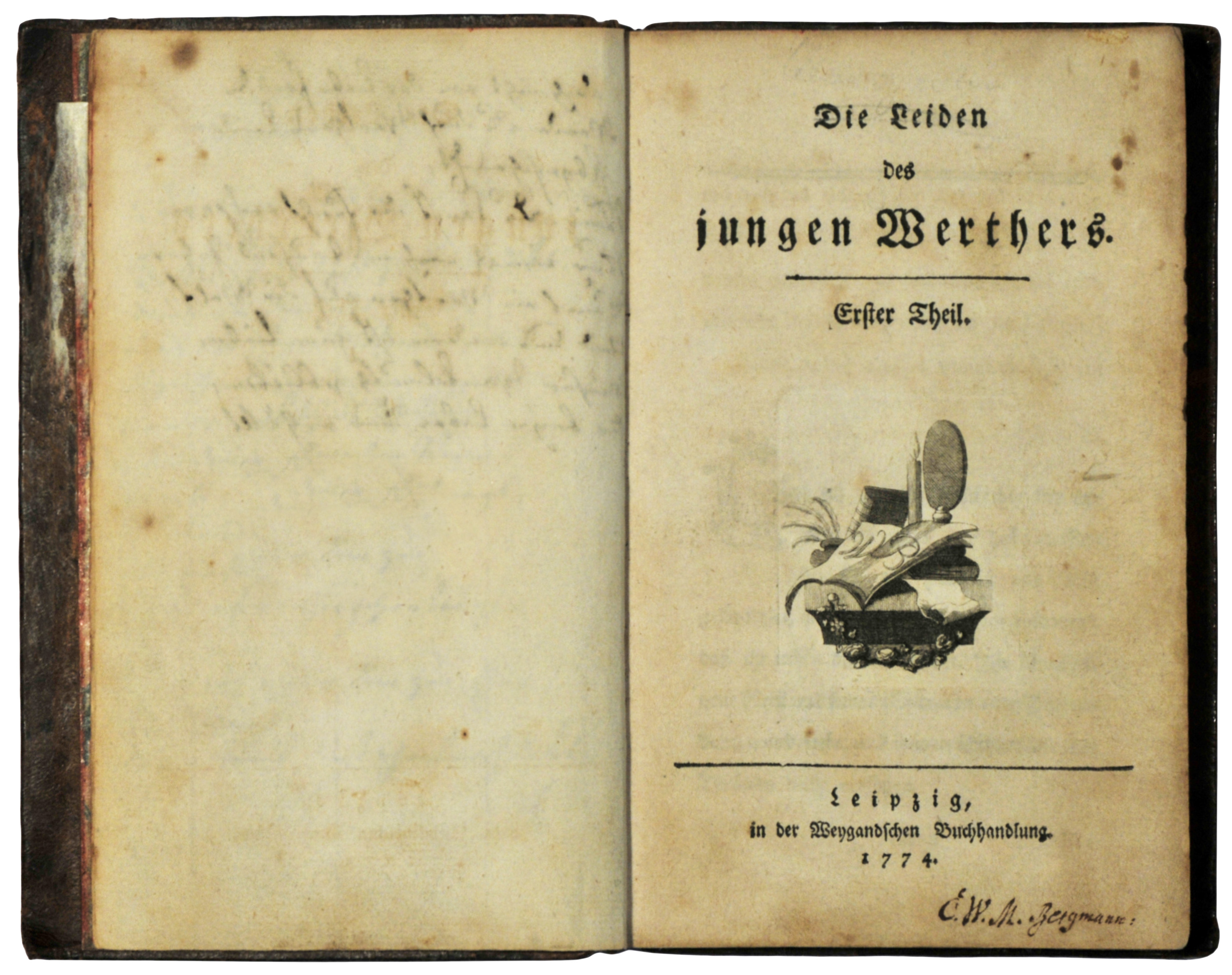

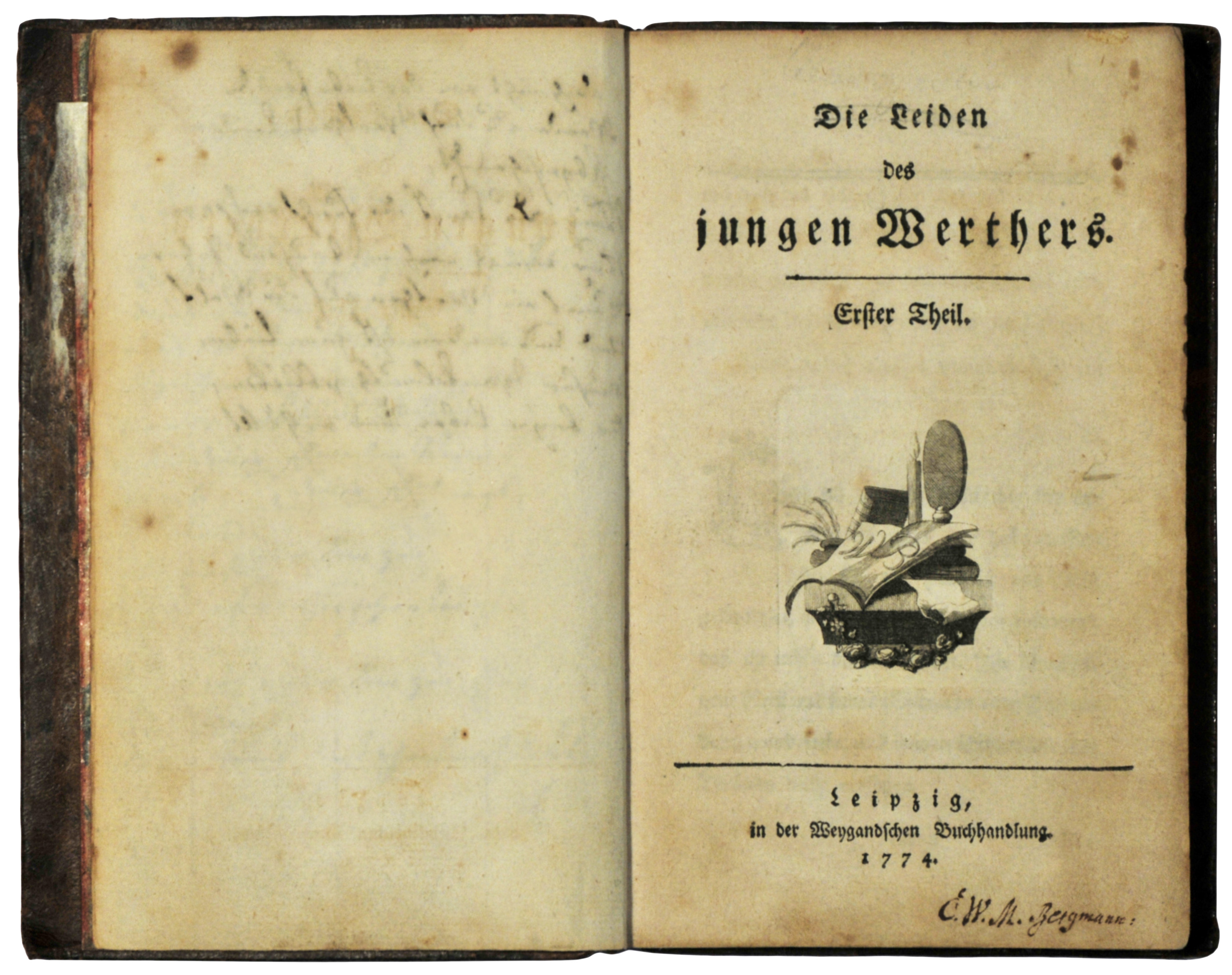

Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus, was published

by the Lackington firm, founded by James Lackington in 1774. Advertised as "The

Cheapest Bookseller in the World," Lackington's business--which both sold and

lent books as well as published them--capitalized on a new, middle-class

reading public. In 1791, the bookseller moved from Chiswell Street to a large

purpose-built store in Finsbury Square, dubbed "The Temple of the Muses"--above

the entrance, an inscription advertised "The Cheapest Books in the World."

Lackington's 1799-1800 catalog, according to the Dictionary of National Biography, boasted nearly 300,000 volumes

available for sale. In 1789, the founder's cousin, George Lackington, took over

operations, and it was here that Shelley's book was sold. William St. Clair,

in The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period,

describes the publication of Frankenstein.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Shelley's husband and noted Romantic poet, arranged the

initial printing with Lackington & Co., which was known to specialize in

books about magic and the supernatural. Turned down by other publishers, likely

for reasons of self-censorship, Frankenstein found a

home at Lackington's. The first run--at 500 copies--was relatively small for

such a well-known shop, but the book was popular and sold well; St. Clair notes

that the first edition of Frankenstein "made more money

than all [Percy] Shelley's works were to fetch in his lifetime" (360). The book

was published anonymously, though because the publishing contract was

negotiated by Percy Shelley, early

reviewers assumed he had authored it, as Germaine Greer suggests.

- [TH]date

The first edition of Frankenstein was written while

Mary Shelley was in the prime of her life, but it was published in January of

1818, shortly after she buried her first child. The second edition, published

in 1831, came after the loss of her husband, most of her children, and her

family. There are many differences between the two texts, which can be viewed in Dana

Wheeles’ public Juxta collation. One of the main structural differences between

the texts is the loss of the three volumes found in the 1818 edition. In the

1831 edition, after the first four letters, the chapters are numbered 1-24,

which not only removes the multiple volumes but also obscures the separated

narratives of Victor, the Creature, and Walton. Another noticeable difference

comes from the removal of the epigraph from Milton’s Paradise

Lost, which, in the beginning of the 1818 edition, announces the key

theme of the novel. Its removal from the 1831 edition obscures the importance

of the allusions to Milton’s work throughout the novel. In the newly-added forward to the 1831 edition, Mary Shelley wrote, somewhat

disingenuously, "I have changed no portion of the story, nor introduced any new

ideas or circumstances." Shelley in fact makes many changes that drastically

change the interpretation and meaning of the text.

First, many of the scientific ideas written about in the 1818 edition are

removed, detaching the novel from an intellectual context and further pressing

it into the fantastical. Shelley also removes many of Elizabeth’s more

independent thoughts about women’s rights as well as her indictment of the

justice system in regards to Justine. Finally, one of the largest differences

between the editions is Victor Frankenstein’s character. Whereas in the 1818

edition, Victor’s own hubris is to blame for the outcome of the Creature, in

the 1831 edition, Victor is at the mercy of fate or chance.

To explore more about the differences between the editions, see Jill Lepore’s

article in The New Yorker, "The Strange and Twisted Life of Frankenstein", Jacqueline Foertsch’s The Right, the Wrong, and the

Ugly: Teaching Shelley's Several "Frankensteins", or James O’Rourke’s

"The 1831 Introduction

and Revisions to Frankenstein: Mary Shelley Dictates

Her Legacy. To explore visual differences between the texts, see the

Shelley-Godwin Archive, which compares facsimiles of the original

manuscripts, and Brigit Katz’ article for The Smithsonian

Magazine, "‘Frankenstein’ Manuscript Shows the Evolution of Mary Shelley’s

Monster."

- [AF]william_godwin

Source: Messrs. Lackington Allen & Co. Temple of the Muses, Finsbury Square (1809), etching by Rudolph Ackerman, via the Lewis Walpole Library of Yale University.

Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus, was published

by the Lackington firm, founded by James Lackington in 1774. Advertised as "The

Cheapest Bookseller in the World," Lackington's business--which both sold and

lent books as well as published them--capitalized on a new, middle-class

reading public. In 1791, the bookseller moved from Chiswell Street to a large

purpose-built store in Finsbury Square, dubbed "The Temple of the Muses"--above

the entrance, an inscription advertised "The Cheapest Books in the World."

Lackington's 1799-1800 catalog, according to the Dictionary of National Biography, boasted nearly 300,000 volumes

available for sale. In 1789, the founder's cousin, George Lackington, took over

operations, and it was here that Shelley's book was sold. William St. Clair,

in The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period,

describes the publication of Frankenstein.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Shelley's husband and noted Romantic poet, arranged the

initial printing with Lackington & Co., which was known to specialize in

books about magic and the supernatural. Turned down by other publishers, likely

for reasons of self-censorship, Frankenstein found a

home at Lackington's. The first run--at 500 copies--was relatively small for

such a well-known shop, but the book was popular and sold well; St. Clair notes

that the first edition of Frankenstein "made more money

than all [Percy] Shelley's works were to fetch in his lifetime" (360). The book

was published anonymously, though because the publishing contract was

negotiated by Percy Shelley, early

reviewers assumed he had authored it, as Germaine Greer suggests.

- [TH]date

The first edition of Frankenstein was written while

Mary Shelley was in the prime of her life, but it was published in January of

1818, shortly after she buried her first child. The second edition, published

in 1831, came after the loss of her husband, most of her children, and her

family. There are many differences between the two texts, which can be viewed in Dana

Wheeles’ public Juxta collation. One of the main structural differences between

the texts is the loss of the three volumes found in the 1818 edition. In the

1831 edition, after the first four letters, the chapters are numbered 1-24,

which not only removes the multiple volumes but also obscures the separated

narratives of Victor, the Creature, and Walton. Another noticeable difference

comes from the removal of the epigraph from Milton’s Paradise

Lost, which, in the beginning of the 1818 edition, announces the key

theme of the novel. Its removal from the 1831 edition obscures the importance

of the allusions to Milton’s work throughout the novel. In the newly-added forward to the 1831 edition, Mary Shelley wrote, somewhat

disingenuously, "I have changed no portion of the story, nor introduced any new

ideas or circumstances." Shelley in fact makes many changes that drastically

change the interpretation and meaning of the text.

First, many of the scientific ideas written about in the 1818 edition are

removed, detaching the novel from an intellectual context and further pressing

it into the fantastical. Shelley also removes many of Elizabeth’s more

independent thoughts about women’s rights as well as her indictment of the

justice system in regards to Justine. Finally, one of the largest differences

between the editions is Victor Frankenstein’s character. Whereas in the 1818

edition, Victor’s own hubris is to blame for the outcome of the Creature, in

the 1831 edition, Victor is at the mercy of fate or chance.

To explore more about the differences between the editions, see Jill Lepore’s

article in The New Yorker, "The Strange and Twisted Life of Frankenstein", Jacqueline Foertsch’s The Right, the Wrong, and the

Ugly: Teaching Shelley's Several "Frankensteins", or James O’Rourke’s

"The 1831 Introduction

and Revisions to Frankenstein: Mary Shelley Dictates

Her Legacy. To explore visual differences between the texts, see the

Shelley-Godwin Archive, which compares facsimiles of the original

manuscripts, and Brigit Katz’ article for The Smithsonian

Magazine, "‘Frankenstein’ Manuscript Shows the Evolution of Mary Shelley’s

Monster."

- [AF]william_godwin

Source: Portrait of William Godwin, by Henry William Pickersgill (died 1875), from the National Portrait Gallery (UK), via Wikimedia Commons. Mary Shelley dedicated Frankenstein to her father, William

Godwin, the well known author of An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and Caleb Williams.

William Godwin was an anarchist and supporter of the French Revolution, and many

of his theories of absolute sovereignty are alluded to within the text of

Frankenstein. Shelley learned much from her father’s library growing up, and thus

was highly influenced by her father’s beliefs. To learn more about Godwin, read

Chapter 4 of Rebecca Baumann’s Frankenstein 200: The Birth,

Life, and Resurrection of Mary Shelley's Monster, "Mary’s Father, William

Godwin". To learn more about Godwin’s influence on Frankenstein, listen to the University of Oxford’s podcast on the

matter. - [AR]political_justice Published in 1793, William Godwin’s

Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on

Morals and Happiness is a philosophical text concerning

politics. Written after the French Revolution, a ten-year period of political

upheaval in France culminating in the overthrow of the monarchy and the

creation of a republic, Godwin’s Enquiry also responds

to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in

France and Thomas Paine’s Rights of

Man--specifically, on questions of authority. Godwin wrote the Enquiry to advocate for the Enlightenment project of

social improvement. His radical writing resonated deeply with Romantic authors,

especially Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Percy Bysshe Shelley. For a more

in-depth look at how this work affected the authors of the Romantic Period see

Andrew McCann’s "William Godwin:

Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Modern Morals and

Manners", and for more information about Godwin’s influence on Mary

Shelley, see an online exhibit Shelley’s Ghost, developed by the

Bodleian Libraries. - [AF]caleb_williamsPublished in May 1794, Things As They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb

Williams tells the story of an impoverished young man named

Caleb Williams, who learns that his wealthy employer, Ferdinando Falkland, is

guilty of murder. When Falkland realizes that Caleb suspects him, he falsely

accuses Caleb of attempted robbery, forcing him to flee the estate. Throughout

the novel, Caleb is accused of various crimes, pursued, robbed, beaten,

arrested, and convicted, but manages ultimately to escape captivity. The novel

is a pointed critique of the English judicial system, particularly its abuse of

power, and continues to develop themes that Godwin presented in his 1793

philosophical treatise, An Enquiry concerning Political

Justice. For a detailed examination of Godwin’s writings and an

overview of Godwinian scholarship, see Pamela Clemit’s "Revisiting William Godwin" from Oxford Handbooks Online. - [AR]mary_shelley

Source: Portrait of William Godwin, by Henry William Pickersgill (died 1875), from the National Portrait Gallery (UK), via Wikimedia Commons. Mary Shelley dedicated Frankenstein to her father, William

Godwin, the well known author of An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and Caleb Williams.

William Godwin was an anarchist and supporter of the French Revolution, and many

of his theories of absolute sovereignty are alluded to within the text of

Frankenstein. Shelley learned much from her father’s library growing up, and thus

was highly influenced by her father’s beliefs. To learn more about Godwin, read

Chapter 4 of Rebecca Baumann’s Frankenstein 200: The Birth,

Life, and Resurrection of Mary Shelley's Monster, "Mary’s Father, William

Godwin". To learn more about Godwin’s influence on Frankenstein, listen to the University of Oxford’s podcast on the

matter. - [AR]political_justice Published in 1793, William Godwin’s

Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on

Morals and Happiness is a philosophical text concerning

politics. Written after the French Revolution, a ten-year period of political

upheaval in France culminating in the overthrow of the monarchy and the

creation of a republic, Godwin’s Enquiry also responds

to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in

France and Thomas Paine’s Rights of

Man--specifically, on questions of authority. Godwin wrote the Enquiry to advocate for the Enlightenment project of

social improvement. His radical writing resonated deeply with Romantic authors,

especially Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Percy Bysshe Shelley. For a more

in-depth look at how this work affected the authors of the Romantic Period see

Andrew McCann’s "William Godwin:

Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Modern Morals and

Manners", and for more information about Godwin’s influence on Mary

Shelley, see an online exhibit Shelley’s Ghost, developed by the

Bodleian Libraries. - [AF]caleb_williamsPublished in May 1794, Things As They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb

Williams tells the story of an impoverished young man named

Caleb Williams, who learns that his wealthy employer, Ferdinando Falkland, is

guilty of murder. When Falkland realizes that Caleb suspects him, he falsely

accuses Caleb of attempted robbery, forcing him to flee the estate. Throughout

the novel, Caleb is accused of various crimes, pursued, robbed, beaten,

arrested, and convicted, but manages ultimately to escape captivity. The novel

is a pointed critique of the English judicial system, particularly its abuse of

power, and continues to develop themes that Godwin presented in his 1793

philosophical treatise, An Enquiry concerning Political

Justice. For a detailed examination of Godwin’s writings and an

overview of Godwinian scholarship, see Pamela Clemit’s "Revisiting William Godwin" from Oxford Handbooks Online. - [AR]mary_shelley

Source: Portrait of Mary Shelley (1840), by Richard Rothwell, via the National Portrait Gallery (UK). Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley was born on August 30, 1797, in London, England, to William Godwin and

famed feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft—the author of The

Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Mary had a difficult

upbringing, as her mother died shortly after her birth and her father remarried to

Mary Jane Clairmont, who had a tenuous relationship with Mary. Mary was never

formally educated but read many of her father’s books and was introduced to many

influential writers like William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Mary,

while on a trip to Scotland visiting family friends, met and fell in love with

Percy Bysshe Shelley, who was already married and also a student of her father.

The two eloped in 1814 and travelled around Europe. It was in Switzerland, with a

cohort made up of the Shelleys, Jane Clairmont, Lord Byron, and John Polidori,

where Mary first began Frankenstein one rainy afternoon during a ghost story

writing exercise. Frankenstein was published in 1818

anonymously with a foreword by Percy Shelley, whom many people assumed wrote the

novel. The novel was a huge success, and is now often considered the first science

fiction novel. After the success of her first novel, Shelley continued to write

but her personal life declined rapidly. She lost three children in her lifetime,

her half-sister committed suicide, and her marriage, riddled with affairs, ended

in 1822 when Percy Shelley drowned in the Gulf of Spezia. Mary died at 53 of brain

cancer on February 1, 1851 in London, England. She was buried at St. Peter's Church in

Bournemouth, laid to rest with the cremated remains of her late husband's heart.

- [TH]event

Frankenstein was created on a rainy afternoon in 1816 when

Mary Godwin (soon to be Mary Shelley), Percy Bysshe

Shelley, Lord Byron, and others were vacationing in Geneva. Lord Byron suggested

a gothic ghost story contest to alleviate their cabin fever--as 1816 was known as

the "year without a summer" due to a volcanic explosion in the Dutch East Indies, causing a long winter in

most of the world. After working their way through established German ghost

stories, the group decided to try their hand at writing their own. For more

information on the circumstances of the creation of Frankenstein and how it affected the development of the text, see

Marshall Brown’s "Frankenstein":

A Child’s Tale", and for images of

Shelley’s manuscript for Frankenstein see the Shelley-Godwin Archive. - [AF]erasmus_darwin

Source: Portrait of Mary Shelley (1840), by Richard Rothwell, via the National Portrait Gallery (UK). Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley was born on August 30, 1797, in London, England, to William Godwin and

famed feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft—the author of The

Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Mary had a difficult

upbringing, as her mother died shortly after her birth and her father remarried to

Mary Jane Clairmont, who had a tenuous relationship with Mary. Mary was never

formally educated but read many of her father’s books and was introduced to many

influential writers like William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Mary,

while on a trip to Scotland visiting family friends, met and fell in love with

Percy Bysshe Shelley, who was already married and also a student of her father.

The two eloped in 1814 and travelled around Europe. It was in Switzerland, with a

cohort made up of the Shelleys, Jane Clairmont, Lord Byron, and John Polidori,

where Mary first began Frankenstein one rainy afternoon during a ghost story

writing exercise. Frankenstein was published in 1818

anonymously with a foreword by Percy Shelley, whom many people assumed wrote the

novel. The novel was a huge success, and is now often considered the first science

fiction novel. After the success of her first novel, Shelley continued to write

but her personal life declined rapidly. She lost three children in her lifetime,

her half-sister committed suicide, and her marriage, riddled with affairs, ended

in 1822 when Percy Shelley drowned in the Gulf of Spezia. Mary died at 53 of brain

cancer on February 1, 1851 in London, England. She was buried at St. Peter's Church in

Bournemouth, laid to rest with the cremated remains of her late husband's heart.

- [TH]event

Frankenstein was created on a rainy afternoon in 1816 when

Mary Godwin (soon to be Mary Shelley), Percy Bysshe

Shelley, Lord Byron, and others were vacationing in Geneva. Lord Byron suggested

a gothic ghost story contest to alleviate their cabin fever--as 1816 was known as

the "year without a summer" due to a volcanic explosion in the Dutch East Indies, causing a long winter in

most of the world. After working their way through established German ghost

stories, the group decided to try their hand at writing their own. For more

information on the circumstances of the creation of Frankenstein and how it affected the development of the text, see

Marshall Brown’s "Frankenstein":

A Child’s Tale", and for images of

Shelley’s manuscript for Frankenstein see the Shelley-Godwin Archive. - [AF]erasmus_darwin Source: Erasmus Darwin, after Joseph Wright (c.1770s), from the National Portrait Gallery (UK).

Erasmus

Darwin (1731-1802), grandfather of Charles Darwin, was a physician and

poet (pictured above is a reprint in the National Portrait Gallery, London by

Joseph Wright based on a work from the 1770’s). An industrialist, free thinker,

and inventor, he is well known for his for his classification novel, Zoonomia, Or, The Laws Of Organic Life which

created classes and categories for animals, and discussed pathology, anatomy, and

psychology. His works influenced many Romantic authors, such as William

Wordsworth, who referenced Darwin in "The Tale of Goody Blake and Harry Gill." For more information, see

Gavin Budge’s article "Erasmus Darwin and the Poetics of William Wordsworth: ‘Excitement without the

Application of Gross and Violent Stimulants’". A radical thinker for the

time, Erasmus Darwin posited the development of life from "one living filament"

(Section XXXIX, Line 8); Darwin’s arguments would later be seen precursors to the

theory of evolution. Darwin also wrote poetry about nature and science, most

notably, The

Loves of the Plants, Economy of

Vegetation, and The Temple

of Nature. His views on living organisms and the creation of life

gives authority to] Victor’s ability to create life and offers a litmus for the

Romantic era skepticism about "playing God." For more information on Erasmus

Darwin in general see Michon Scott’s website Strange Science; to

see Darwin’s influence on both Romantic and Victorian writers, see Thomas Hart’s

article on The

Victorian Web. - [AF]iliadThe Iliad, composed in approximately

the 9th century BCE, is an epic poem in elevated and formal verse, narrating the

events that occurred in the ninth year of the attack on Troy. The story begins

with Agamemnon, the wanax of Mycenae and commander of the

various independent Achaean kingdoms, insulting Achilles. Turmoil ensues among the

Achaeans, who have been laying siege to the City of Troy for nearly ten years. The

story includes the death of Achilles’ closest friend Patroclus, which causes

Achilles to defeat and defile his murderer, Hector, Prince of Troy. The story

concludes with Achilles surrendering Hector’s body to King Priam, father of

Hector, and his recognition of a kinship between them through grief. See MIT’s

full text version

of The Iliad translated by Samuel Butler. - [AF]tragedyTragedy is an elevated literary form that originated in ancient Greece. According

to Aristotle’s Poetics, "Tragedy is, then, a representation of an action

that is heroic and complete and of a certain magnitude—by means of language

enriched with all kinds of ornament, each used separately in the different

parts of the play: it represents men in action and does not use narrative, and

through pity and fear it effects relief to these and similar emotions."

(1449b), Romantic authors were greatly influenced by the ancient tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides,

however they often turned the genre on its head. While tragedy in the original

sense featured a hero of noble birth, the Romantics, like Samuel

Taylor Coleridge, preferred to consider the common man. Often, Romantics

turned the argument inward, invoking Shakespeare’s tragedies in lieu of Ancient

ones (Macbeth,Hamlet, Othello). - [AF]william_shakespeare

Source: Erasmus Darwin, after Joseph Wright (c.1770s), from the National Portrait Gallery (UK).

Erasmus

Darwin (1731-1802), grandfather of Charles Darwin, was a physician and

poet (pictured above is a reprint in the National Portrait Gallery, London by

Joseph Wright based on a work from the 1770’s). An industrialist, free thinker,

and inventor, he is well known for his for his classification novel, Zoonomia, Or, The Laws Of Organic Life which

created classes and categories for animals, and discussed pathology, anatomy, and

psychology. His works influenced many Romantic authors, such as William

Wordsworth, who referenced Darwin in "The Tale of Goody Blake and Harry Gill." For more information, see

Gavin Budge’s article "Erasmus Darwin and the Poetics of William Wordsworth: ‘Excitement without the

Application of Gross and Violent Stimulants’". A radical thinker for the

time, Erasmus Darwin posited the development of life from "one living filament"

(Section XXXIX, Line 8); Darwin’s arguments would later be seen precursors to the

theory of evolution. Darwin also wrote poetry about nature and science, most

notably, The

Loves of the Plants, Economy of

Vegetation, and The Temple

of Nature. His views on living organisms and the creation of life

gives authority to] Victor’s ability to create life and offers a litmus for the

Romantic era skepticism about "playing God." For more information on Erasmus

Darwin in general see Michon Scott’s website Strange Science; to

see Darwin’s influence on both Romantic and Victorian writers, see Thomas Hart’s

article on The

Victorian Web. - [AF]iliadThe Iliad, composed in approximately

the 9th century BCE, is an epic poem in elevated and formal verse, narrating the

events that occurred in the ninth year of the attack on Troy. The story begins

with Agamemnon, the wanax of Mycenae and commander of the

various independent Achaean kingdoms, insulting Achilles. Turmoil ensues among the

Achaeans, who have been laying siege to the City of Troy for nearly ten years. The

story includes the death of Achilles’ closest friend Patroclus, which causes

Achilles to defeat and defile his murderer, Hector, Prince of Troy. The story

concludes with Achilles surrendering Hector’s body to King Priam, father of

Hector, and his recognition of a kinship between them through grief. See MIT’s

full text version

of The Iliad translated by Samuel Butler. - [AF]tragedyTragedy is an elevated literary form that originated in ancient Greece. According

to Aristotle’s Poetics, "Tragedy is, then, a representation of an action

that is heroic and complete and of a certain magnitude—by means of language

enriched with all kinds of ornament, each used separately in the different

parts of the play: it represents men in action and does not use narrative, and

through pity and fear it effects relief to these and similar emotions."

(1449b), Romantic authors were greatly influenced by the ancient tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides,

however they often turned the genre on its head. While tragedy in the original

sense featured a hero of noble birth, the Romantics, like Samuel

Taylor Coleridge, preferred to consider the common man. Often, Romantics

turned the argument inward, invoking Shakespeare’s tragedies in lieu of Ancient

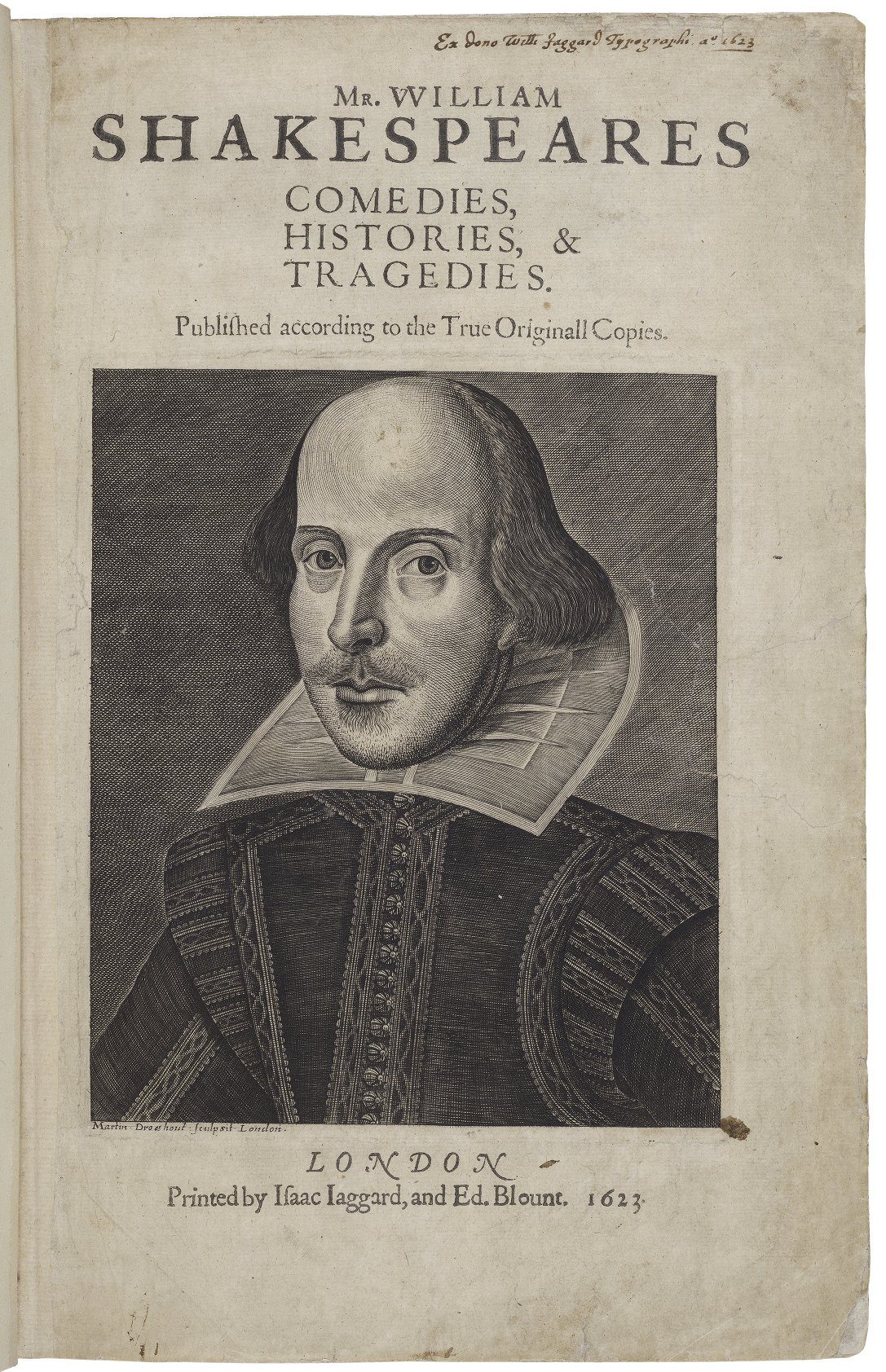

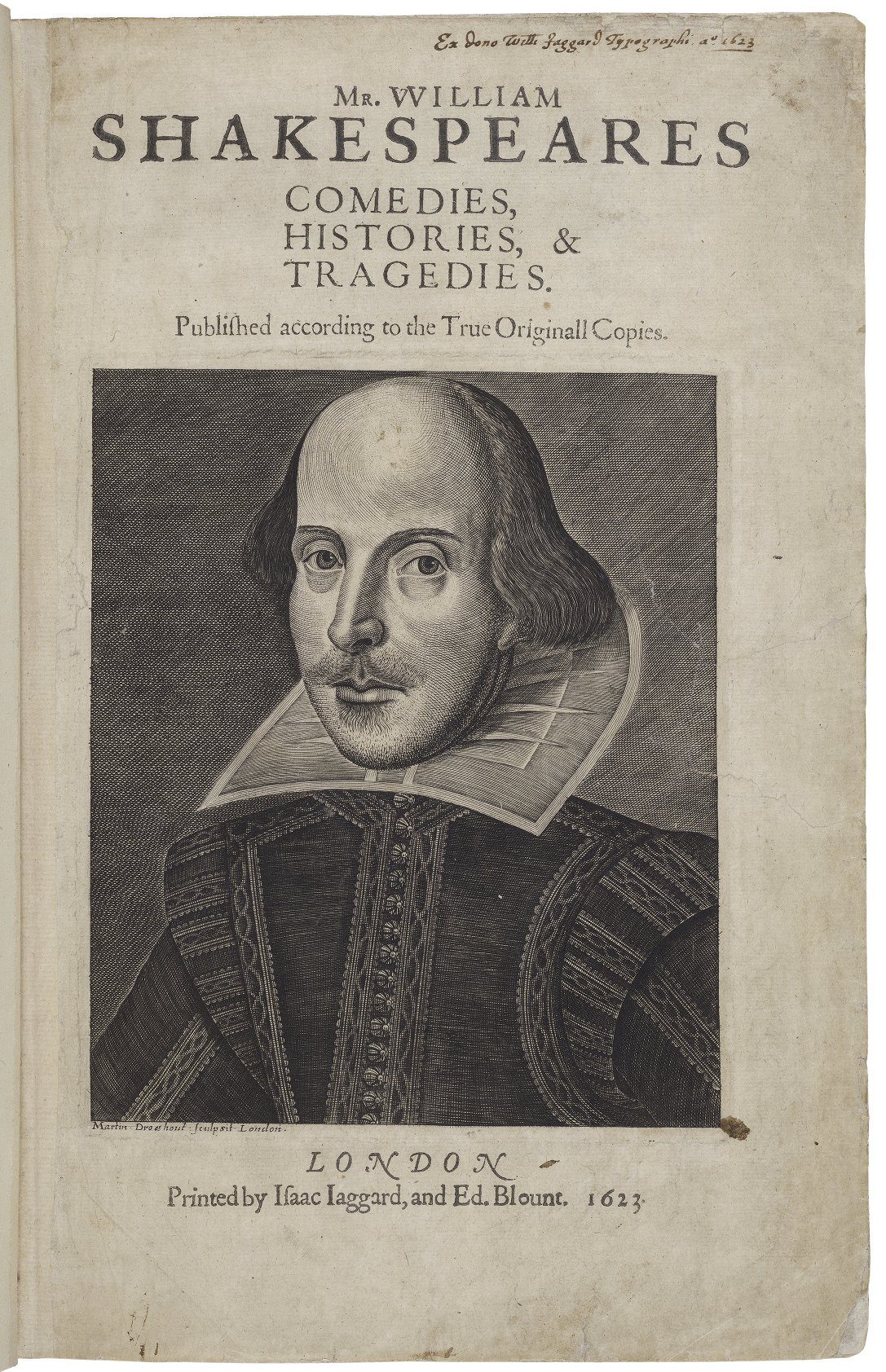

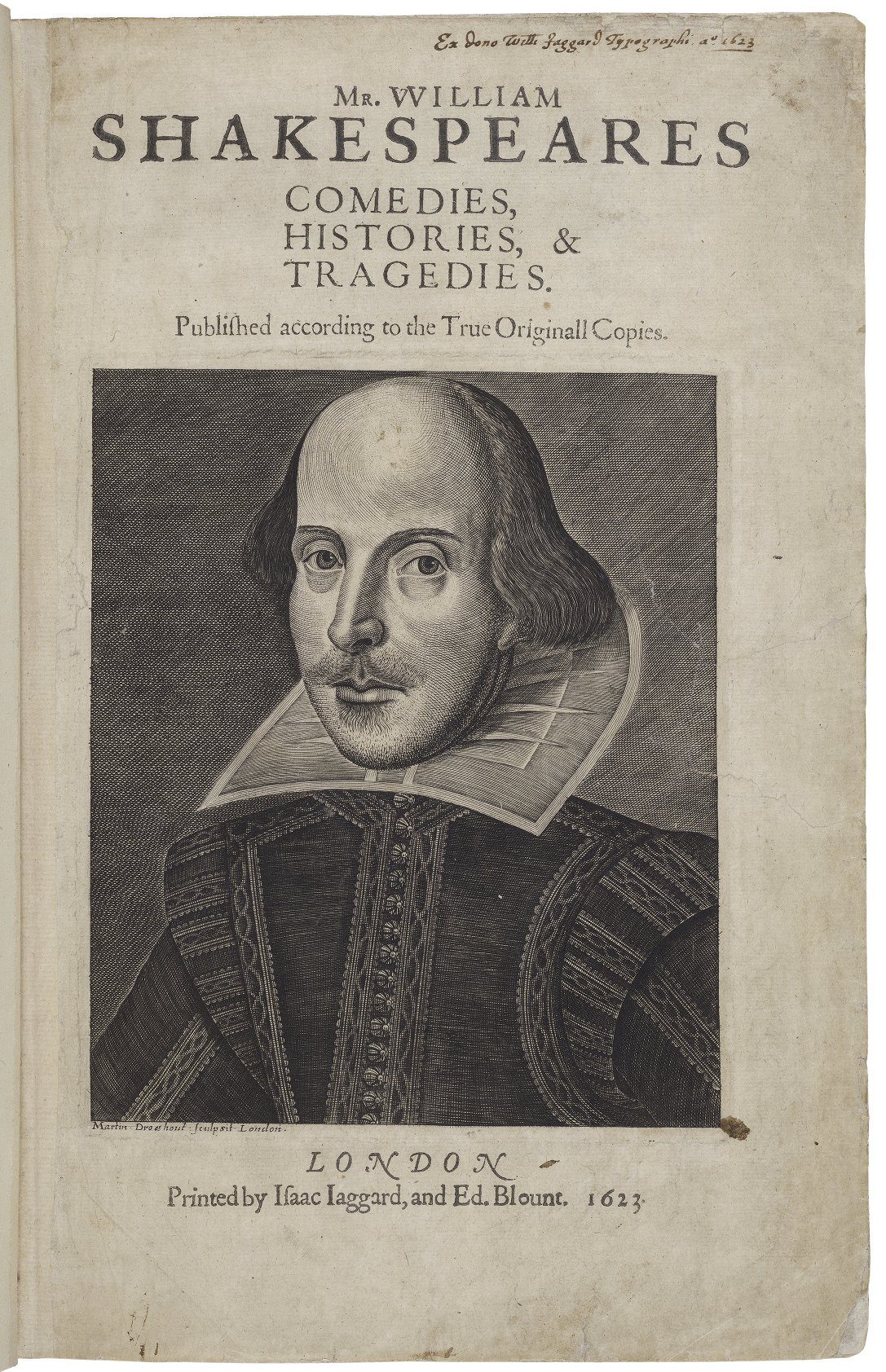

ones (Macbeth,Hamlet, Othello). - [AF]william_shakespeare Source: Engraved title page with portrait from Folger First Folio 1 (1623), via the Folger Shakespeare Library. William Shakespeare (1564-1616) is one of the greatest writers in the English

language, known for composing 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and two long narrative poems.

Shakespeare’s works, known for his innovative, vivid use of language and his

exploration of individual subjectivity, were of special interest to the Romantics.

As Jonathan Bate argues in Shakespeare and the English

Romantic Imagination (1989), the idea of natural genius and the

veneration of the creative imagination was essential to the Romantic ideology, and

Shakespeare became a key sign of natural creative genius. The "bardolatry" that

began in the mid-eighteenth century, particularly through the actor David Garrick’s (1717-1779) energies,

came to a head in the Romantic era, and has in many ways persisted to this day.

For more information on the role of Shakespeare in the Romantic era, see Bate’s

important monograph as well as Joseph M. Ortiz’s

edited collection, Shakespeare and the Culture of Romanticism

. Mary Shelley would have been familiar with his works both through

her education at the hands of her father, William Godwin, and through her close

relationship with Byron, Shelley, Polidori, and other Romantics. Godwin, with his second wife Mary Jane Clairmont, created and published works

in a juvenlie library series for the improvement of young readers’ imaginations

that included, among histories of Greece and bible stories, Tales From Shakespeare.. All of these authors influenced her

writing, and Shakespeare colored her entire life; Shelley had lines from The Tempest carved into her husband’s tombstone. To read

more about Shakespeare’s influence on Mary Shelley’s life and writing see Robert

Sawyer’s article "Mary Shelley and Shakespeare:

Monstrous Creations" or David Lee Clark’s article, "Shelley and Shakespeare".

For a full list of Shakespeare’s works, as well as summaries and criticisms, see

the Folger Shakespeare

Library. - [AF]tempestThe Tempest

is a comedy written in 1610 by William

Shakespeare tellning the story of the banished Duke of Milan, Prospero,

who has recreated his home on an island using magic--and usurped the native

inhabitants of the island to do so, imprisoning Sycorax and enslaving her son,

Caliban. Prospero causes the shipwreck of the King of Naples, Alonso, and his

brother, Antonio, who, twelve years earlier had conspired for Prospero’s position

thus banishing him from the kingdom. During the tale, Miranda, Prospero’s

daughter, and Ferdinand, Alonso’s son, fall in love, but must survive the tests

placed upon them by Prospero. Other castaways from the shipwreck land on the

island and conspire to destroy Prospero but in the end common ground and love

triumph. Explore more of the text on the Folger Shakespeare

Library. - [AF]midsummer

Source: Engraved title page with portrait from Folger First Folio 1 (1623), via the Folger Shakespeare Library. William Shakespeare (1564-1616) is one of the greatest writers in the English

language, known for composing 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and two long narrative poems.

Shakespeare’s works, known for his innovative, vivid use of language and his

exploration of individual subjectivity, were of special interest to the Romantics.

As Jonathan Bate argues in Shakespeare and the English

Romantic Imagination (1989), the idea of natural genius and the

veneration of the creative imagination was essential to the Romantic ideology, and

Shakespeare became a key sign of natural creative genius. The "bardolatry" that

began in the mid-eighteenth century, particularly through the actor David Garrick’s (1717-1779) energies,

came to a head in the Romantic era, and has in many ways persisted to this day.

For more information on the role of Shakespeare in the Romantic era, see Bate’s

important monograph as well as Joseph M. Ortiz’s

edited collection, Shakespeare and the Culture of Romanticism

. Mary Shelley would have been familiar with his works both through

her education at the hands of her father, William Godwin, and through her close

relationship with Byron, Shelley, Polidori, and other Romantics. Godwin, with his second wife Mary Jane Clairmont, created and published works

in a juvenlie library series for the improvement of young readers’ imaginations

that included, among histories of Greece and bible stories, Tales From Shakespeare.. All of these authors influenced her

writing, and Shakespeare colored her entire life; Shelley had lines from The Tempest carved into her husband’s tombstone. To read

more about Shakespeare’s influence on Mary Shelley’s life and writing see Robert

Sawyer’s article "Mary Shelley and Shakespeare:

Monstrous Creations" or David Lee Clark’s article, "Shelley and Shakespeare".

For a full list of Shakespeare’s works, as well as summaries and criticisms, see

the Folger Shakespeare

Library. - [AF]tempestThe Tempest

is a comedy written in 1610 by William

Shakespeare tellning the story of the banished Duke of Milan, Prospero,

who has recreated his home on an island using magic--and usurped the native

inhabitants of the island to do so, imprisoning Sycorax and enslaving her son,

Caliban. Prospero causes the shipwreck of the King of Naples, Alonso, and his

brother, Antonio, who, twelve years earlier had conspired for Prospero’s position

thus banishing him from the kingdom. During the tale, Miranda, Prospero’s

daughter, and Ferdinand, Alonso’s son, fall in love, but must survive the tests

placed upon them by Prospero. Other castaways from the shipwreck land on the

island and conspire to destroy Prospero but in the end common ground and love

triumph. Explore more of the text on the Folger Shakespeare

Library. - [AF]midsummer

Source: Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing (1786), watercolor and graphite on paper by William Blake, from the Tate Britain via Wikimedia Commons.

Midsummer Night’s

Dream

(1595) is a comedy by William Shakespeare. A play within a play, the story

is set in a fairyland Athenian forest during the marriage of Theseus, the Duke of

Athens, to Hippolyta, the Queen of the Amazons. The play’s complex subplots

involve a variety of complementary stories. The play opens with a love triangle

between Hermia, who is in love with Lysander but is being forced to marry

Demetrius by her father Egeus. Helena, Hermia’s best friend is in love with

Demetrius. On another side of the story are the "Rude Mechanicals," a group of six

skilled laborers who are planning a performance of Pyramus and

Thisbe. The last subplot involves the king and queen of the fairies,

Oberon and Titania, who are in an argument over a small child Titania is

protecting from Oberon. Oberon, in his frustration over Titania’s disobedience,

sends his sprite, Robin "Puck" Goodfellow, to create a love potion to shame

Titania into obedience. Puck wreaks havoc on all the characters, causing the men

to fall in love with Helena and rebuff Hermia, turning Bottom part donkey, and

prompting Titania to fall in love with Bottom. During this confusion, Oberon

steals the child from Titania, upon which success he orders Puck to set everything

straight. The play concludes with the Mechanicals’ inexpert play-within-a-play,

staged for the marriage festivities of Theseus and Hippolyta. Explore more about

the text at the Folger

Shakespeare Library or see David Wiles Shakespeare and Carnival: After Bakhtin,

especially chapter 4, "The Carnivalesque in A Midsummer Night's Dream." - [AF]john_milton

Source: Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing (1786), watercolor and graphite on paper by William Blake, from the Tate Britain via Wikimedia Commons.

Midsummer Night’s

Dream

(1595) is a comedy by William Shakespeare. A play within a play, the story

is set in a fairyland Athenian forest during the marriage of Theseus, the Duke of

Athens, to Hippolyta, the Queen of the Amazons. The play’s complex subplots

involve a variety of complementary stories. The play opens with a love triangle

between Hermia, who is in love with Lysander but is being forced to marry

Demetrius by her father Egeus. Helena, Hermia’s best friend is in love with

Demetrius. On another side of the story are the "Rude Mechanicals," a group of six

skilled laborers who are planning a performance of Pyramus and

Thisbe. The last subplot involves the king and queen of the fairies,

Oberon and Titania, who are in an argument over a small child Titania is

protecting from Oberon. Oberon, in his frustration over Titania’s disobedience,

sends his sprite, Robin "Puck" Goodfellow, to create a love potion to shame

Titania into obedience. Puck wreaks havoc on all the characters, causing the men

to fall in love with Helena and rebuff Hermia, turning Bottom part donkey, and

prompting Titania to fall in love with Bottom. During this confusion, Oberon

steals the child from Titania, upon which success he orders Puck to set everything

straight. The play concludes with the Mechanicals’ inexpert play-within-a-play,

staged for the marriage festivities of Theseus and Hippolyta. Explore more about

the text at the Folger

Shakespeare Library or see David Wiles Shakespeare and Carnival: After Bakhtin,

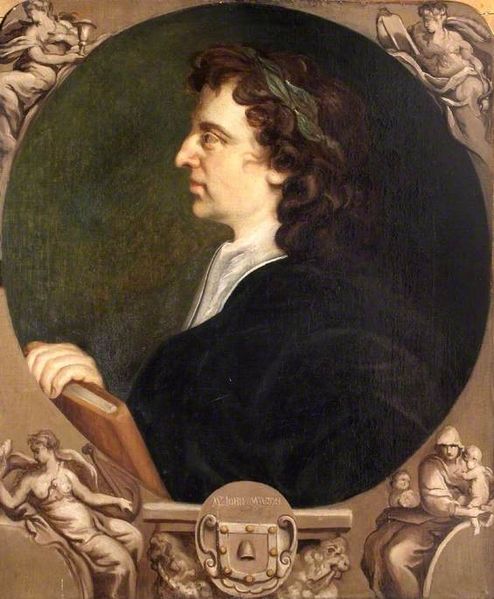

especially chapter 4, "The Carnivalesque in A Midsummer Night's Dream." - [AF]john_milton Source: Portrait in profile of John Milton (1690), attributed to Godfrey Kneller, via Wikimedia Commons.John Milton (1608-1674) was an English poet most notably known for Paradise Lost, a twelve-volume epic poem in blank

verse, dramatizing the Fall of mankind (Encyclopedia

Britannica). - [TH]novelThroughout the eighteenth century, the

novel as a modern form of entertainment accessible to a wide, middling-class, and

generally-educated audience grew. For more information on the "humble" novel, see John Mullan's "The Rise of the Novel" at the British Library. - [TH]originMary Shelley, then Godwin, began writing the story that

would become Frankenstein during a vacation in Geneva with

Claire Clairmont, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Polidori, during

which Byron challenged the group to each write a ghost story. It was inspired in

part by a dream, which she describes in the introduction to the 1831 edition; in

part by her mother's, Mary Wollstonecraft's, death just after giving birth to her;

and in part by contemporary scientific discoveries around resucsitation and galvanism.

To read the Shelley's introduction to the 1831 edition, where Shelley describes

the origin of "[her] hideous progeny," see Project

Gutenberg. For an interesting, accessible essay about the novel's

authorship and reception, see "The Strange and Twisted Life of 'Frankenstein'", by Jill Lepore, in The New Yorker. - [TH]time

According to a footnote in the 3rd Broadview

edition of Frankenstein, or; The Modern

Prometheus, the novel takes place in 1796. If this is true,

the entire tale takes place around the date of the author's birth and her

mother Mary Wollstonecraft's death.

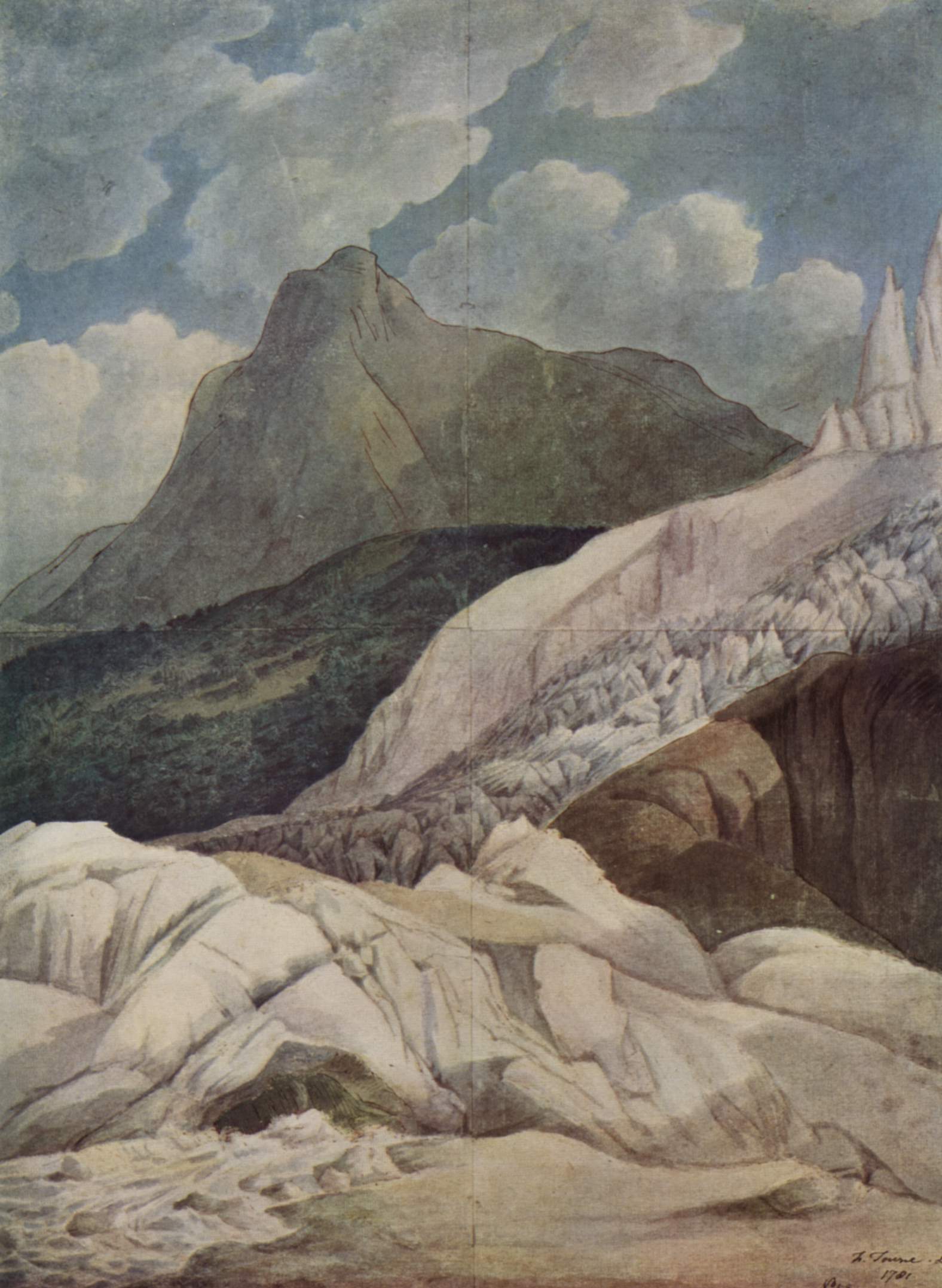

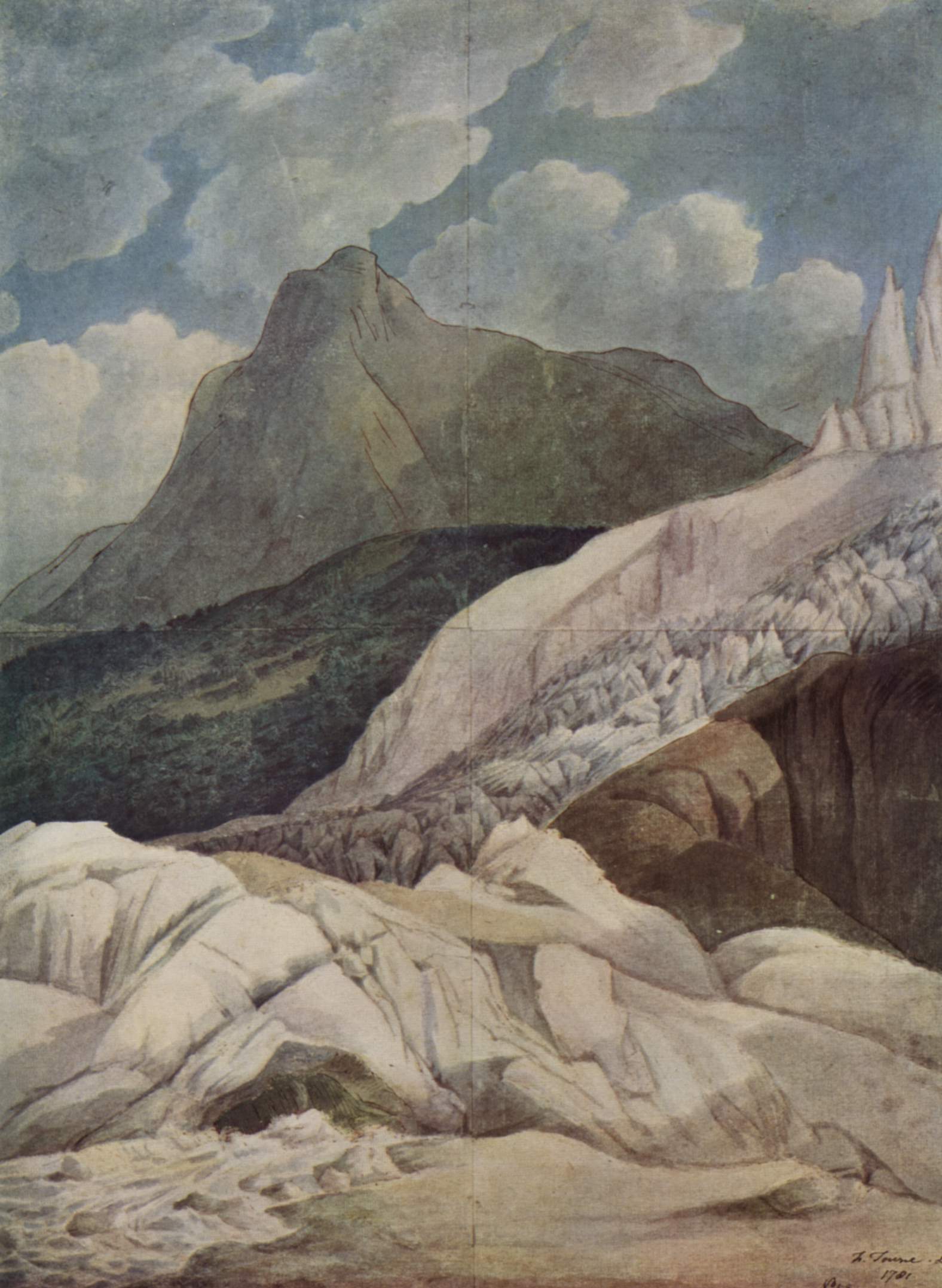

- [AF]arctic

Source: Portrait in profile of John Milton (1690), attributed to Godfrey Kneller, via Wikimedia Commons.John Milton (1608-1674) was an English poet most notably known for Paradise Lost, a twelve-volume epic poem in blank

verse, dramatizing the Fall of mankind (Encyclopedia

Britannica). - [TH]novelThroughout the eighteenth century, the

novel as a modern form of entertainment accessible to a wide, middling-class, and

generally-educated audience grew. For more information on the "humble" novel, see John Mullan's "The Rise of the Novel" at the British Library. - [TH]originMary Shelley, then Godwin, began writing the story that

would become Frankenstein during a vacation in Geneva with

Claire Clairmont, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Polidori, during

which Byron challenged the group to each write a ghost story. It was inspired in

part by a dream, which she describes in the introduction to the 1831 edition; in

part by her mother's, Mary Wollstonecraft's, death just after giving birth to her;

and in part by contemporary scientific discoveries around resucsitation and galvanism.

To read the Shelley's introduction to the 1831 edition, where Shelley describes

the origin of "[her] hideous progeny," see Project

Gutenberg. For an interesting, accessible essay about the novel's

authorship and reception, see "The Strange and Twisted Life of 'Frankenstein'", by Jill Lepore, in The New Yorker. - [TH]time

According to a footnote in the 3rd Broadview

edition of Frankenstein, or; The Modern

Prometheus, the novel takes place in 1796. If this is true,

the entire tale takes place around the date of the author's birth and her

mother Mary Wollstonecraft's death.

- [AF]arctic

Source: Portrait of John Ross (c.1833), by an unknown painter of the British school of the 19th century, from in the Royal Museums Greenwich via Wikimedia Commons.

According to Kathryn Shultz in "Literature's Arctic

Obsession," Shelley--like many during the early nineteenth

century--was intrigued by the prospect of arctic exploration, as her frequent

allusions to Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" and her letters make

clear. While Shelley may have added the arctic setting as "an afterthought"

after reading about attempts to discover the long-elusive Northwest passage, by

the time Frankenstein was published, two major

expeditions were underway; the Passage would be discovered in 1850 after many

deaths on the ice. As Shultz notes, "the book reminded readers that their world

was already full of Dr. Frankensteins." For further reading, see

"'A Paradise of My Own Creation': Frankenstein and the Improbable Romance of

Polar Expedition," by Jessica Richard. The image here shows a portrait

the Arctic explorer John Ross (1777-1856). - [TH]electromagnetism

Source: Portrait of John Ross (c.1833), by an unknown painter of the British school of the 19th century, from in the Royal Museums Greenwich via Wikimedia Commons.

According to Kathryn Shultz in "Literature's Arctic

Obsession," Shelley--like many during the early nineteenth

century--was intrigued by the prospect of arctic exploration, as her frequent

allusions to Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" and her letters make

clear. While Shelley may have added the arctic setting as "an afterthought"

after reading about attempts to discover the long-elusive Northwest passage, by

the time Frankenstein was published, two major

expeditions were underway; the Passage would be discovered in 1850 after many

deaths on the ice. As Shultz notes, "the book reminded readers that their world

was already full of Dr. Frankensteins." For further reading, see

"'A Paradise of My Own Creation': Frankenstein and the Improbable Romance of

Polar Expedition," by Jessica Richard. The image here shows a portrait

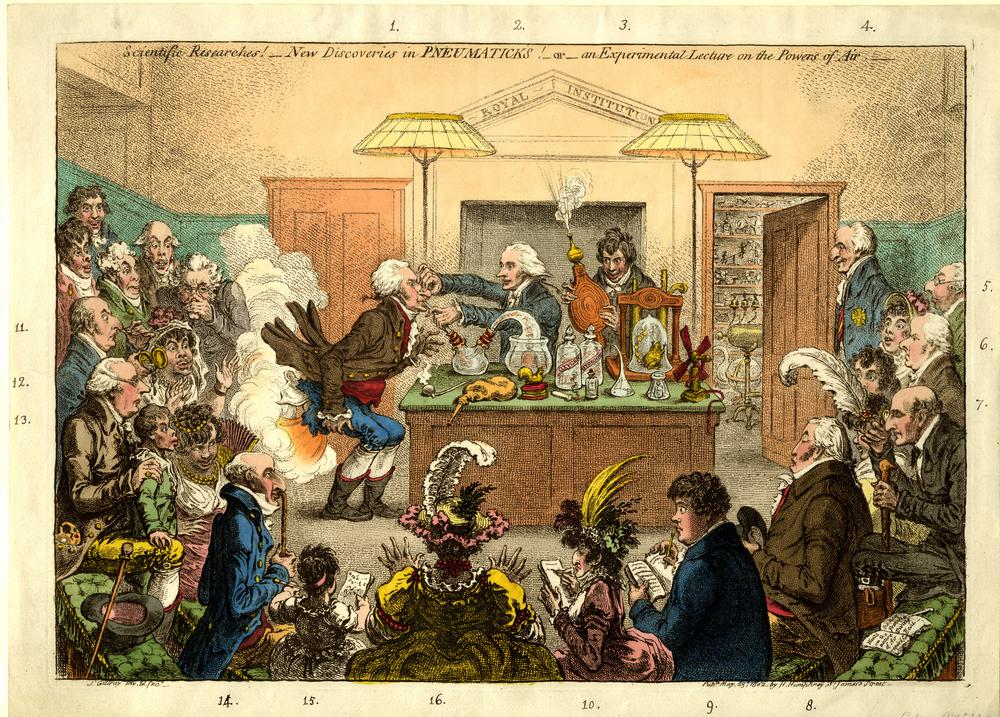

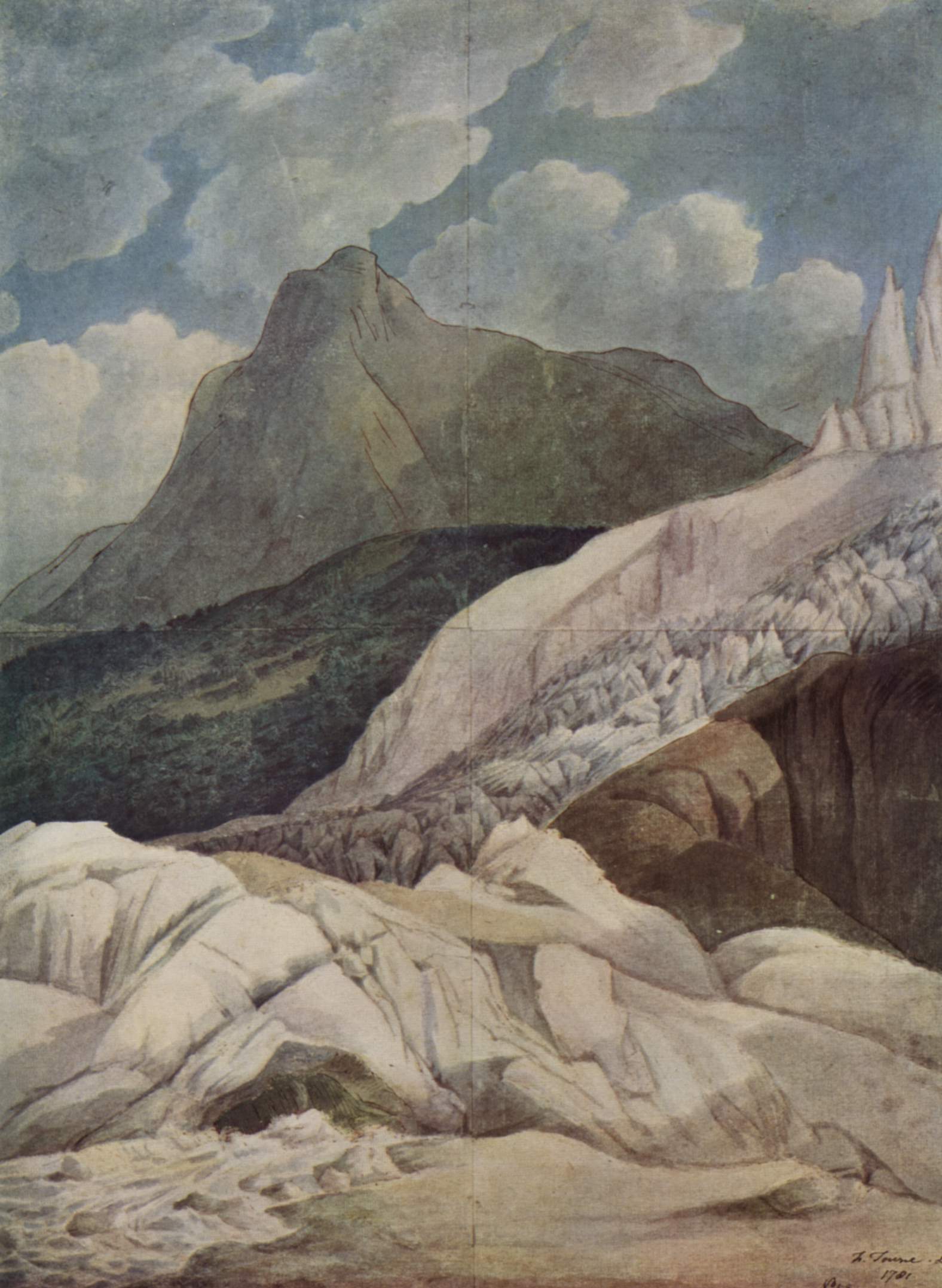

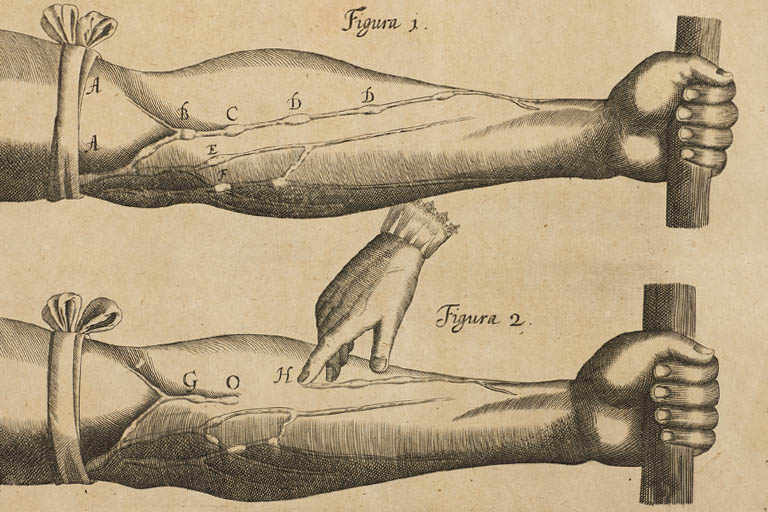

the Arctic explorer John Ross (1777-1856). - [TH]electromagnetism Source: A photograph of an azimuthal compass (18th century), taken by Luis Garcia, via Wikimedia Commons. The compas is housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain. From the 13th through the 19th centuries, scholars and scientists were

investigating the nature of electromagnetism, though, as noted in the

American Physical Society newsletter of July 2008, most people thought

they were separate forces. The Economy of Vegetation, a 1791 poem by Erasmus

Darwin, Charles Darwin’s grandfather, speculates on the nature of

electromagnetism (see canto 2 lines 193ff). In 1820, two years after the

publication of Frankenstein, Danish scientist Hans Christian Oersted discovered

that electric current could produce a magnetic effect on a compass, which

normally points due north--toward the Earth’s magnetic core. For more

information on Darwin’s influence in the late eighteenth century, see Jenny Uglow’s review of his work in The

Guardian. - [TH]enthusiasmEnthusiasm is an important concept in the development of

Romanticism. Deriving from the Greek word "enthous," meannig possessed or

inspired by a god, the concept of enthusiasm was linked to religious fanaticism (particularly Methodism) during the early

eighteenth century and described by philosophers like Locke and Hume as an

error in thinking that reason and reflection could correct. Enthusiasm was

also, however, understood as the ability to "see the truth transparently and

spontaneously without mediation" (Mee 8). Jon Mee, in Romanticism, Enthusiasm, and

Regulation, goes on to note: "Although it was often associated

with the sort of implosion of the self that came from the prophet retiring into

the wilderness, a species of melancholia and gloomy introspection, it was also

routinely construed in terms of the delirium of the senses that manifested

itself in the mania of the crowd" (10-11). Closely related to concepts of

imagination and fancy, enthusiasm is a complex term that suggests many of the

negative aspects of the Romantic sensibility. For Wordsworth and Coleridge,

enthusiasm is a kind of corruption of or detour in the imagination (Mee 12).

- [TH]HomerHomer is the figure credited

with the composition of two epic poems, The Iliad and

The Odyssey, considered to be the first extant works

of Greek literature. Though modern scholarship questions the existence of a

single person called "Homer," the idea of such authorship has had an enduring

interpretive effect from ancient times to the present. Known as the "Father of

Western Literature," Homer is credited with a number of hymns and lesser works

in addition to The Iliad and The

Odyssey. If such an individual existed, scholars have suggested his

floruit as anywhere between the 9th to 7th centuries BCE. To learn more about

Homer, see Suzanne Saïd’s entry in the Oxford Classical

Dictionary. - [AF]the_Mariner

Source: A photograph of an azimuthal compass (18th century), taken by Luis Garcia, via Wikimedia Commons. The compas is housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain. From the 13th through the 19th centuries, scholars and scientists were

investigating the nature of electromagnetism, though, as noted in the

American Physical Society newsletter of July 2008, most people thought

they were separate forces. The Economy of Vegetation, a 1791 poem by Erasmus

Darwin, Charles Darwin’s grandfather, speculates on the nature of

electromagnetism (see canto 2 lines 193ff). In 1820, two years after the

publication of Frankenstein, Danish scientist Hans Christian Oersted discovered

that electric current could produce a magnetic effect on a compass, which

normally points due north--toward the Earth’s magnetic core. For more

information on Darwin’s influence in the late eighteenth century, see Jenny Uglow’s review of his work in The

Guardian. - [TH]enthusiasmEnthusiasm is an important concept in the development of

Romanticism. Deriving from the Greek word "enthous," meannig possessed or

inspired by a god, the concept of enthusiasm was linked to religious fanaticism (particularly Methodism) during the early

eighteenth century and described by philosophers like Locke and Hume as an

error in thinking that reason and reflection could correct. Enthusiasm was

also, however, understood as the ability to "see the truth transparently and

spontaneously without mediation" (Mee 8). Jon Mee, in Romanticism, Enthusiasm, and

Regulation, goes on to note: "Although it was often associated

with the sort of implosion of the self that came from the prophet retiring into

the wilderness, a species of melancholia and gloomy introspection, it was also

routinely construed in terms of the delirium of the senses that manifested

itself in the mania of the crowd" (10-11). Closely related to concepts of

imagination and fancy, enthusiasm is a complex term that suggests many of the

negative aspects of the Romantic sensibility. For Wordsworth and Coleridge,

enthusiasm is a kind of corruption of or detour in the imagination (Mee 12).

- [TH]HomerHomer is the figure credited

with the composition of two epic poems, The Iliad and

The Odyssey, considered to be the first extant works

of Greek literature. Though modern scholarship questions the existence of a

single person called "Homer," the idea of such authorship has had an enduring

interpretive effect from ancient times to the present. Known as the "Father of

Western Literature," Homer is credited with a number of hymns and lesser works

in addition to The Iliad and The

Odyssey. If such an individual existed, scholars have suggested his

floruit as anywhere between the 9th to 7th centuries BCE. To learn more about

Homer, see Suzanne Saïd’s entry in the Oxford Classical

Dictionary. - [AF]the_Mariner

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rime_of_the_Ancient_Mariner-Albatross-Dore.jpgIn this excerpt from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (451- 456),

the Mariner has killed the albatross and the other sailors turn on him, viewing

his act of violence as a sin against God and nature. The luck of the ship

dissipates, and they are becalmed on the ocean. The Mariner watches as each of

the sailors die of thirst, while he alone is saved. This direct allusion

highlights the similarities between the Mariner and Frankenstein, who are both

reeling after accomplishing their respective goals--killing the albatross and

creating a sentient being--and both in the process of telling their stories.

The use of the quote is two-fold; it highlights Frankenstein’s isolation and

his decision to abandon his creature, but it also juxtaposes the Mariner’s

violence with Frankenstein’s act of creation. Explore more about Coleridge’s

poem in William Christie’s “The Search for

Meaning in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,". See Michelle Levy’s

article, “Discovery and the

Domestic Affections in Coleridge and Shelley," for a discussion of

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s influence on Mary Shelley. - [AF]Rime

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rime_of_the_Ancient_Mariner-Albatross-Dore.jpgIn this excerpt from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (451- 456),

the Mariner has killed the albatross and the other sailors turn on him, viewing

his act of violence as a sin against God and nature. The luck of the ship

dissipates, and they are becalmed on the ocean. The Mariner watches as each of

the sailors die of thirst, while he alone is saved. This direct allusion

highlights the similarities between the Mariner and Frankenstein, who are both

reeling after accomplishing their respective goals--killing the albatross and

creating a sentient being--and both in the process of telling their stories.

The use of the quote is two-fold; it highlights Frankenstein’s isolation and

his decision to abandon his creature, but it also juxtaposes the Mariner’s

violence with Frankenstein’s act of creation. Explore more about Coleridge’s

poem in William Christie’s “The Search for

Meaning in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,". See Michelle Levy’s

article, “Discovery and the

Domestic Affections in Coleridge and Shelley," for a discussion of

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s influence on Mary Shelley. - [AF]Rime

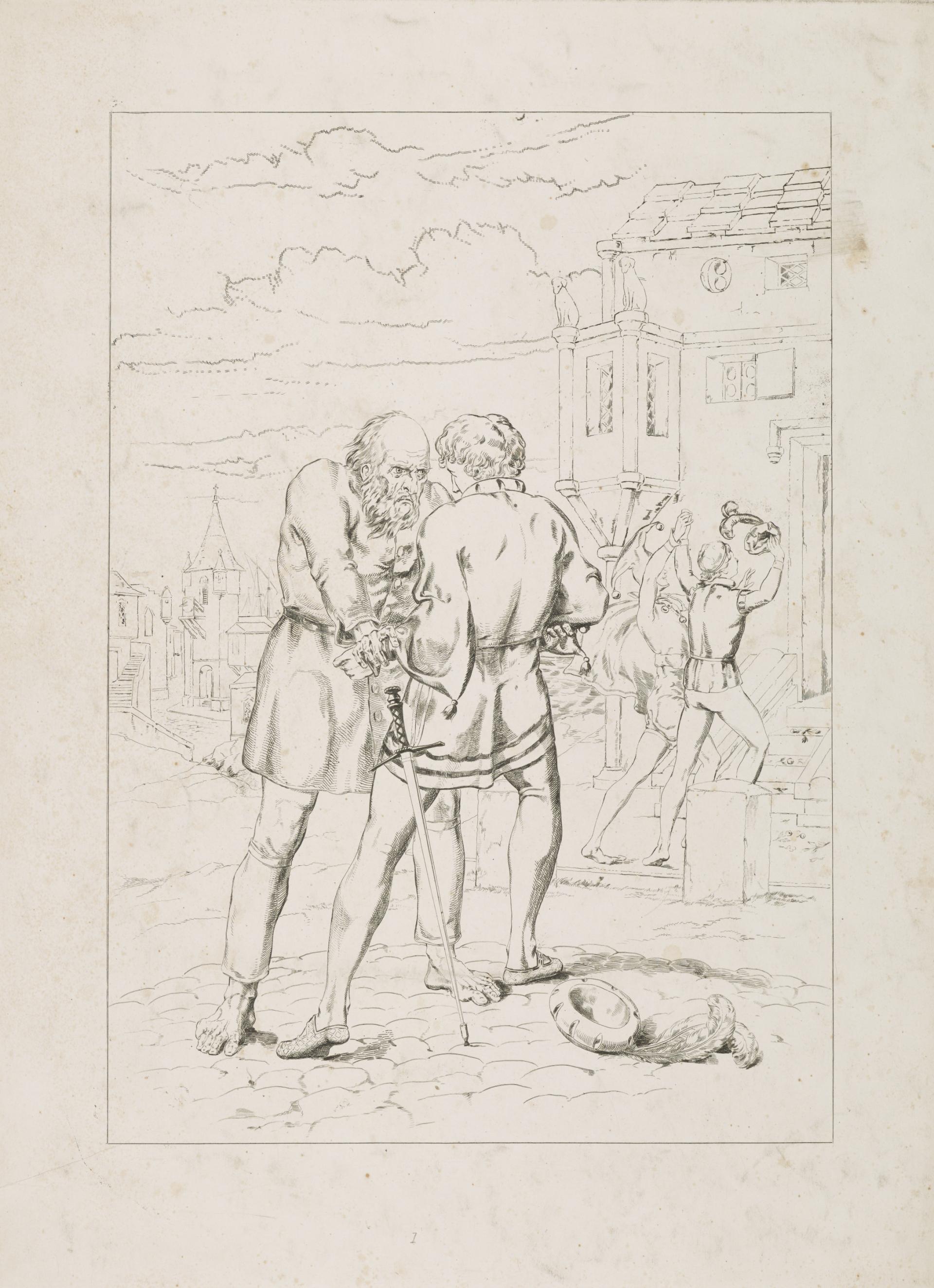

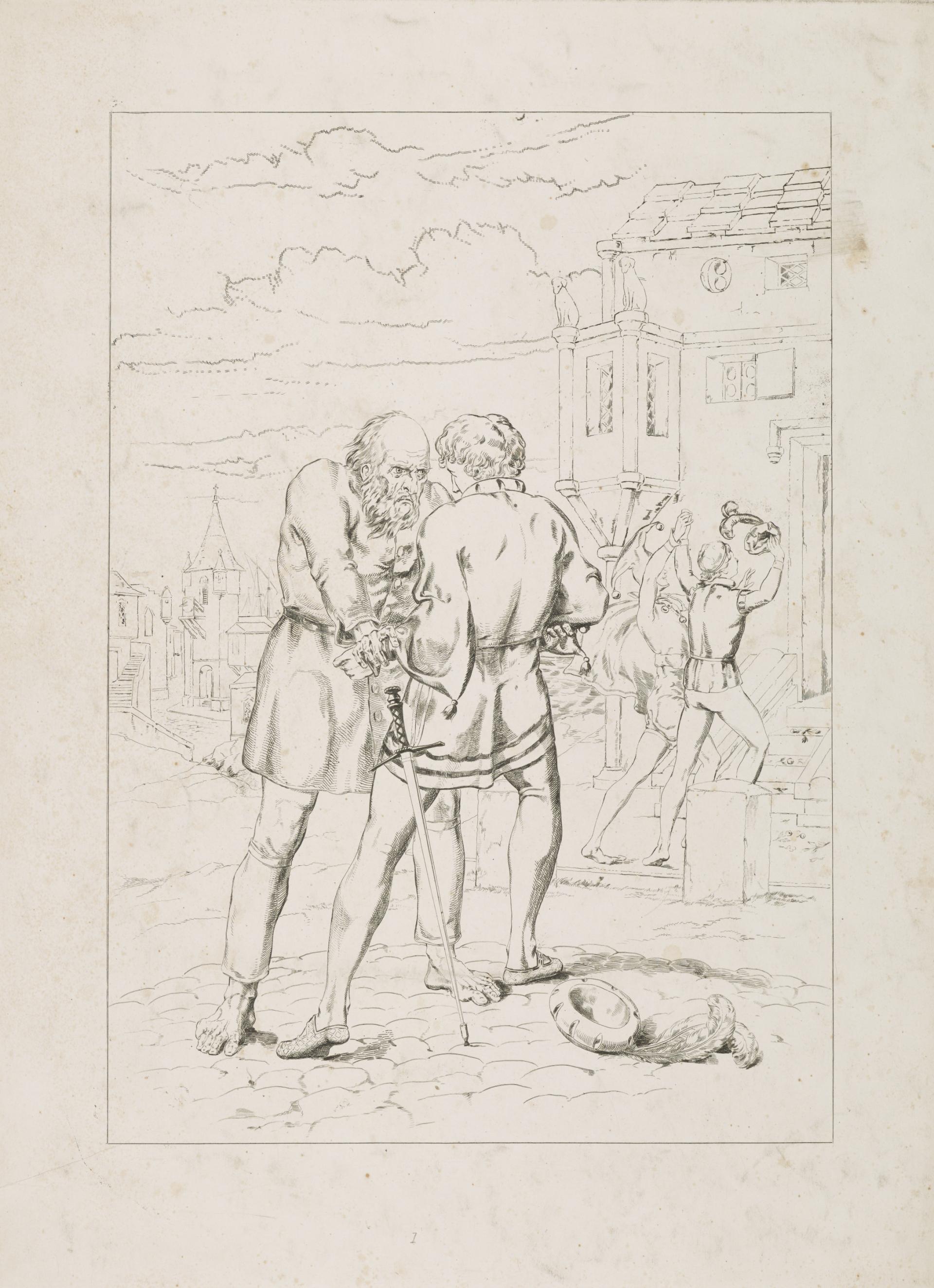

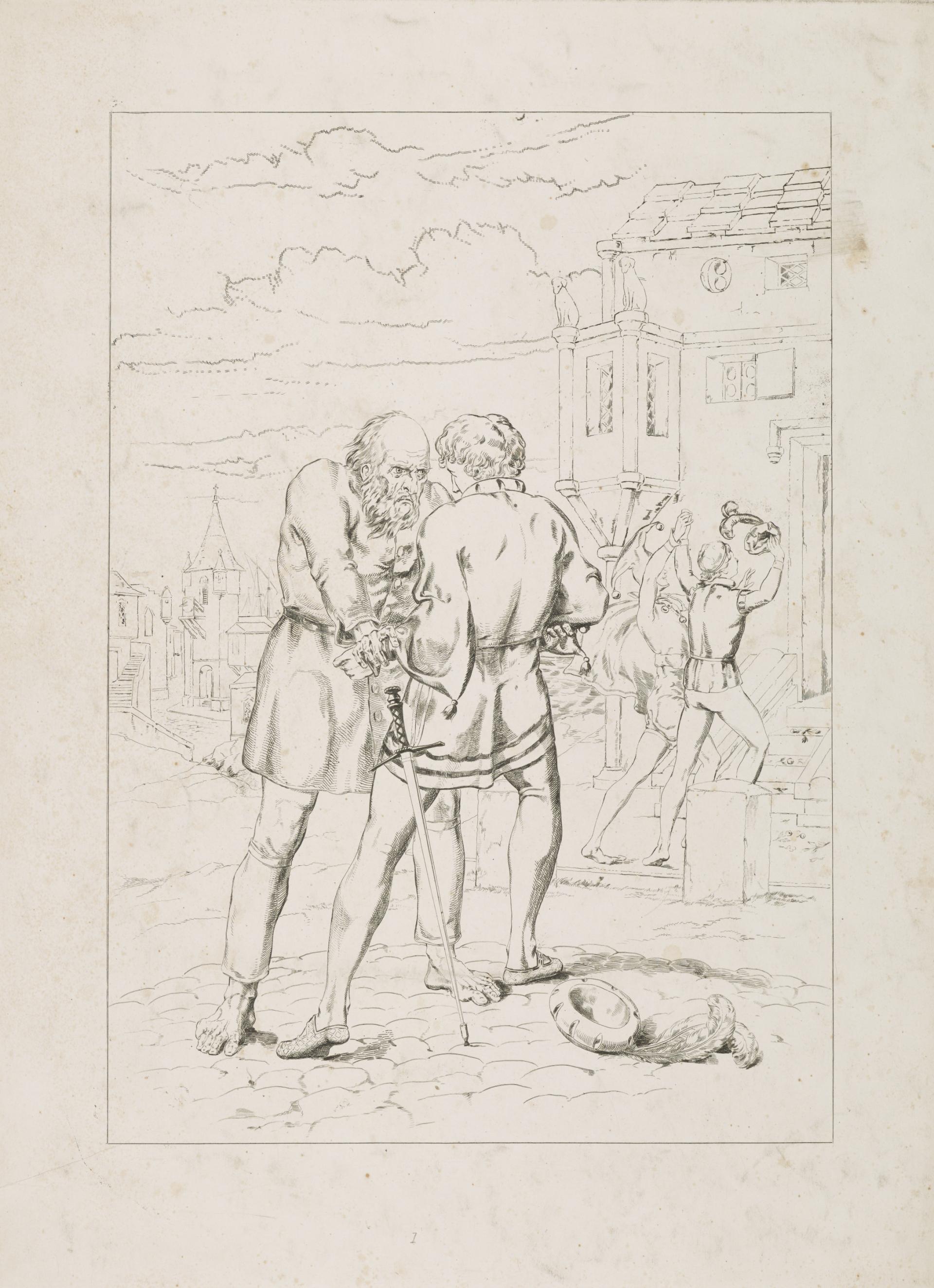

Source: The Ancient Mariner Stops the Wedding Guest (before letters) from 'The Rime of the Ancient Mariner' (Plate II), by David Scott (1806-1849), National Galleries of Scotland. This is a reference to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1798 poem,

Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Coleridge’s

most famous poem is a tale narrated by an ancient sailor returned from a

long, ambitious journey during which, having shot and killed an

albatross, all other members of the crew die and the mariner is cursed.

The poem foregrounds the act of storytelling; the mariner with his "strange power of speech" (587) is compelled to tell his story,

and others, due to its fantastical nature, are compelled to pay

attention. The illustration here depicts the Ancient Mariner telling

his tale to the Wedding Guest, who "cannot chuse but to hear" (18). To

learn more about Coleridge’s poem, published as the opening poem in Lyrical Ballads

, read Seamus Perry’s introduction at the British Library. - [AF]Plain_work"Plain work" here refers to sewing and needlework that

is "plain," as opposed to "fancy." Caroline Beaufort, however, is also

making money by taking orders for piece work, which refers to any work paid

for "by the piece" or according to what is produced, like modern factory

work. - [TH]cousin_marriageMarriage between cousins was a common practice in

history, often deployed to maintain family property and wealth. Read more

about marriage between cousins in Adam Kuper’s Incest and

Influence especially the Coda, or his

article in Past and Present "Incest, Cousin Marriage, and

the Origin of the Human Sciences in Nineteenth-Century England." In

the 1818 edition of Frankenstein, Elizabeth Lavenza,

is Victor’s first cousin on his father’s side; however, in the 2nd edition

of 1831, Mary Shelley revises this plot point to make Elizabeth an unknown

orphan and no longer related to the Frankensteins. She is instead rescued by

Victor Frankenstein’s mother. To learn more of Mary Shelley’s revisions

between the first and second editions see the annotation linked to the

publication date in the Preface of the novel, or head to Dana Wheeles’ Juxta

Commons comparison

of the 1818 and 1831 editions of Frankenstein.

- [AF]fancyFancy and imaginagion are important concepts in that shifted in meaning

througout the eighteenth century, being associated with mental creativity

and wit. For William Wordsworth, fancy is, like the imagination, a force for

association and creation; in his Preface of 1815, he writes that fancy is

"capricious as the accidents of things... Fancy depends upon the rapidity

and profusion with which she scatters her thoughts and images" (xxxiv-xxxv). Fancy is more "given to quicken and to beguile the temporal

part of our nature," while "Imagination [works] to incite and to support the

eternal" (xxxv). For Coleridge, fancy is inferior to imagination, lighter,

and is more like wit in terms of its power to make connections between

ideas; Coleridge explores the distinctions between primary imagination,

secondary imagination, and fancy in Book 13 of Biographia

Literaria (1817). For a good general historical overview, see Fancy and Imagination (1969) by R. L. Brett.

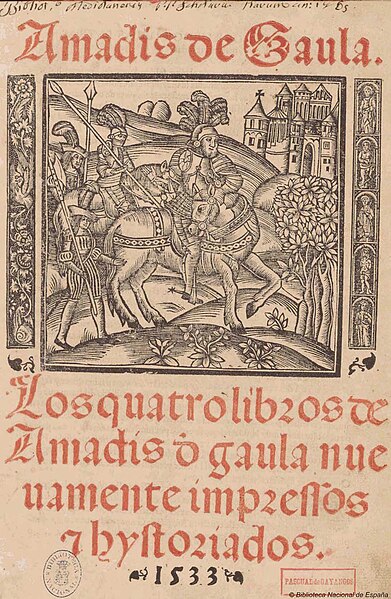

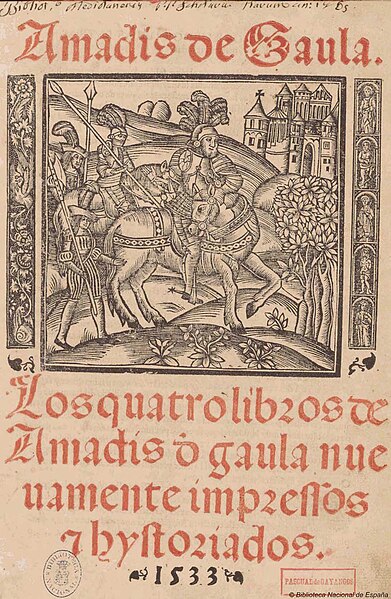

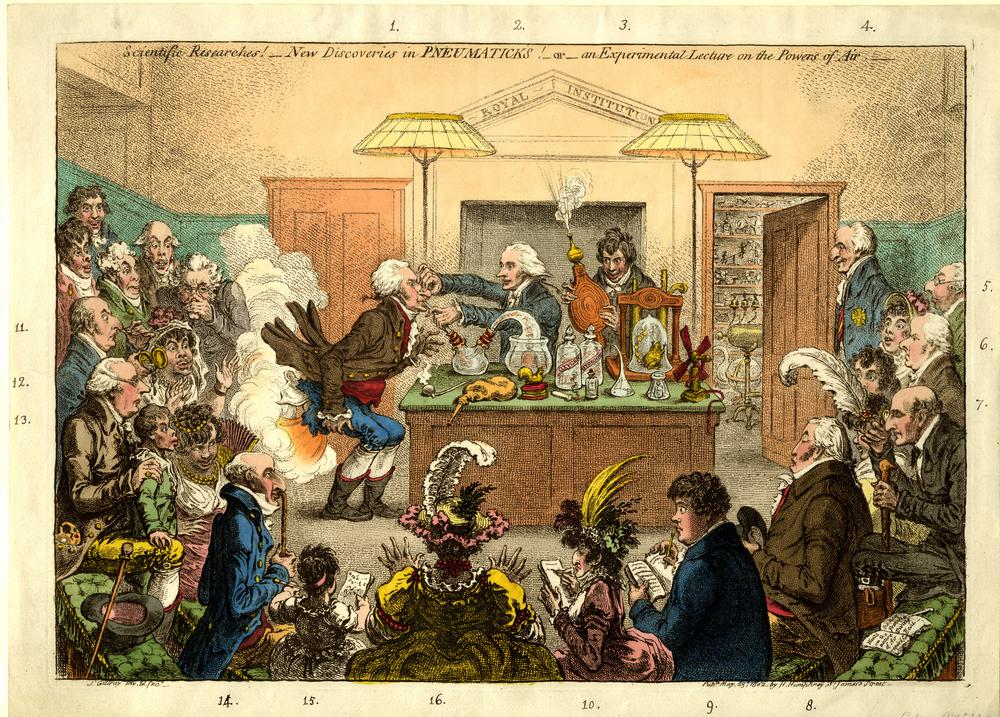

- [TH]chivalric_romanceChivalric romance, according Oxford Reference, is a genre of literature that began in

Medieval Europe and flourished into the 17th century. Chivalric romances,

usually written in poetic verse, tell stories of the great deeds of

knight-errantry. Chivalry, in particular, refers to "an idealized code of

civilized behaviour that combines loyalty, honour, and courtly love." These

sorts of stories were often called "romans," from which the word "romance"

derives. Formally loose or episodic in structure, heroic romances written in

later periods "deliberately eschew[ed] contemporaneity"; their plots

featured courtly lovers engaged in "heroic stories of love and war in a

remote and idealized past" (1046), as Shellinger states in the Encyclopedia of the Novel. Some representative heroic

romances include Euphues by John Lyly, L'Astrée by Honore d'Urfé, Artamène by Madame de Scudéry, Orlando

Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto, and Amadís de

Gaula by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. Romance of this sort declined

in popularity during the 18th century, but during the Romantic period--so

named by later scholars for its turn toward these very romantic ideals of

individualism, heroism, and the imagination--such stories were revived. For

a fuller discussion of the origins and meaning of the word "romantic" see

Michael

Ferber’s Romanticism: A Very Short Introduction

(3-7), and for a broader overview of the medieval genre, see the Encyclopedia Britannica’s entry on Romance. - [TH]Orlando_Furioso

Source: The Ancient Mariner Stops the Wedding Guest (before letters) from 'The Rime of the Ancient Mariner' (Plate II), by David Scott (1806-1849), National Galleries of Scotland. This is a reference to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1798 poem,

Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Coleridge’s

most famous poem is a tale narrated by an ancient sailor returned from a

long, ambitious journey during which, having shot and killed an

albatross, all other members of the crew die and the mariner is cursed.

The poem foregrounds the act of storytelling; the mariner with his "strange power of speech" (587) is compelled to tell his story,

and others, due to its fantastical nature, are compelled to pay

attention. The illustration here depicts the Ancient Mariner telling

his tale to the Wedding Guest, who "cannot chuse but to hear" (18). To

learn more about Coleridge’s poem, published as the opening poem in Lyrical Ballads

, read Seamus Perry’s introduction at the British Library. - [AF]Plain_work"Plain work" here refers to sewing and needlework that

is "plain," as opposed to "fancy." Caroline Beaufort, however, is also

making money by taking orders for piece work, which refers to any work paid

for "by the piece" or according to what is produced, like modern factory

work. - [TH]cousin_marriageMarriage between cousins was a common practice in

history, often deployed to maintain family property and wealth. Read more

about marriage between cousins in Adam Kuper’s Incest and

Influence especially the Coda, or his

article in Past and Present "Incest, Cousin Marriage, and

the Origin of the Human Sciences in Nineteenth-Century England." In

the 1818 edition of Frankenstein, Elizabeth Lavenza,

is Victor’s first cousin on his father’s side; however, in the 2nd edition

of 1831, Mary Shelley revises this plot point to make Elizabeth an unknown

orphan and no longer related to the Frankensteins. She is instead rescued by

Victor Frankenstein’s mother. To learn more of Mary Shelley’s revisions

between the first and second editions see the annotation linked to the

publication date in the Preface of the novel, or head to Dana Wheeles’ Juxta

Commons comparison

of the 1818 and 1831 editions of Frankenstein.

- [AF]fancyFancy and imaginagion are important concepts in that shifted in meaning

througout the eighteenth century, being associated with mental creativity

and wit. For William Wordsworth, fancy is, like the imagination, a force for

association and creation; in his Preface of 1815, he writes that fancy is

"capricious as the accidents of things... Fancy depends upon the rapidity

and profusion with which she scatters her thoughts and images" (xxxiv-xxxv). Fancy is more "given to quicken and to beguile the temporal

part of our nature," while "Imagination [works] to incite and to support the

eternal" (xxxv). For Coleridge, fancy is inferior to imagination, lighter,

and is more like wit in terms of its power to make connections between

ideas; Coleridge explores the distinctions between primary imagination,

secondary imagination, and fancy in Book 13 of Biographia

Literaria (1817). For a good general historical overview, see Fancy and Imagination (1969) by R. L. Brett.

- [TH]chivalric_romanceChivalric romance, according Oxford Reference, is a genre of literature that began in

Medieval Europe and flourished into the 17th century. Chivalric romances,

usually written in poetic verse, tell stories of the great deeds of

knight-errantry. Chivalry, in particular, refers to "an idealized code of

civilized behaviour that combines loyalty, honour, and courtly love." These

sorts of stories were often called "romans," from which the word "romance"

derives. Formally loose or episodic in structure, heroic romances written in

later periods "deliberately eschew[ed] contemporaneity"; their plots

featured courtly lovers engaged in "heroic stories of love and war in a

remote and idealized past" (1046), as Shellinger states in the Encyclopedia of the Novel. Some representative heroic

romances include Euphues by John Lyly, L'Astrée by Honore d'Urfé, Artamène by Madame de Scudéry, Orlando

Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto, and Amadís de

Gaula by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. Romance of this sort declined

in popularity during the 18th century, but during the Romantic period--so

named by later scholars for its turn toward these very romantic ideals of

individualism, heroism, and the imagination--such stories were revived. For

a fuller discussion of the origins and meaning of the word "romantic" see

Michael

Ferber’s Romanticism: A Very Short Introduction

(3-7), and for a broader overview of the medieval genre, see the Encyclopedia Britannica’s entry on Romance. - [TH]Orlando_Furioso

Source: Ruggiero Rescuing Angelica (1819), oil painting by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, from the Louvre Museum via Wikimedia Commons.

Orlando

Furioso is an epic poem published in 1532 by the Italian

poet Ludovico Arisoto, and an example of the "books of chivalry and romance"

that Clerval enjoys. Set in the 8th century, Orlando

Furioso tells the story of the protagonist Orlando, leader of the

Christian knights, fighting the so-called Saracens for

control of Europe during the reign of Charlemagne (Charles I). As the first

lines of the poem point out, its subject is "Dames, knights, and arms, and

love! The deeds that spring / From courteous minds, and venturous feats"

(1.1-2). The chivalric romance combines realism and fantasy throughout its

46 cantos. First published in English translation in 1591, Orlando Furioso is a source for Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing. While the story is episodic, one

of the most important plots focuses on Orlando’s dangerous passion for the

pagan princess Angelica, which is the cause of his titular madness. Ariosto’s tale was also famously

illustrated by the late nineteenth-century artist Gustave Doré.

- [AF]Robin_Hood

Source: Ruggiero Rescuing Angelica (1819), oil painting by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, from the Louvre Museum via Wikimedia Commons.

Orlando

Furioso is an epic poem published in 1532 by the Italian

poet Ludovico Arisoto, and an example of the "books of chivalry and romance"

that Clerval enjoys. Set in the 8th century, Orlando

Furioso tells the story of the protagonist Orlando, leader of the

Christian knights, fighting the so-called Saracens for

control of Europe during the reign of Charlemagne (Charles I). As the first

lines of the poem point out, its subject is "Dames, knights, and arms, and

love! The deeds that spring / From courteous minds, and venturous feats"

(1.1-2). The chivalric romance combines realism and fantasy throughout its

46 cantos. First published in English translation in 1591, Orlando Furioso is a source for Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing. While the story is episodic, one

of the most important plots focuses on Orlando’s dangerous passion for the

pagan princess Angelica, which is the cause of his titular madness. Ariosto’s tale was also famously

illustrated by the late nineteenth-century artist Gustave Doré.

- [AF]Robin_Hood Source: Photograph of the Robin Hood plaque at Nottingham Castle, taken by RichardUK2014, via Wikimedia Commons. Robin Hood is a legendary outlaw who stole from the rich to give to the

poor. Numerous ballads have been written about the character, who may have

been based on a real

person. Robin Hood lived the true heroic code, protecting women,

supporting the lowly, and remained faithful to the monarch. Read more about

Robin Hood in Howard Pyle’s The Merry

Adventures of Robin Hood, one of the more popular

adaptations of the legend written in 1883. - [AF]Amadis_de_Gaula

Source: Photograph of the Robin Hood plaque at Nottingham Castle, taken by RichardUK2014, via Wikimedia Commons. Robin Hood is a legendary outlaw who stole from the rich to give to the

poor. Numerous ballads have been written about the character, who may have

been based on a real

person. Robin Hood lived the true heroic code, protecting women,

supporting the lowly, and remained faithful to the monarch. Read more about

Robin Hood in Howard Pyle’s The Merry

Adventures of Robin Hood, one of the more popular

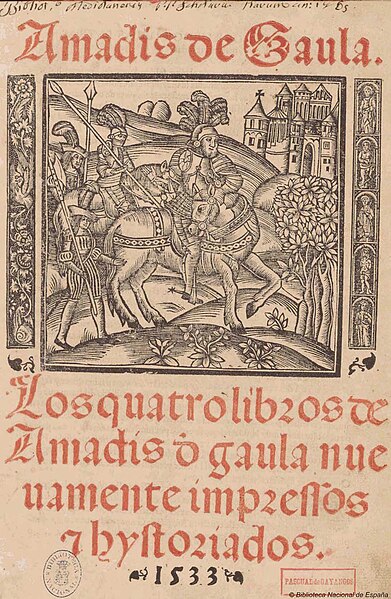

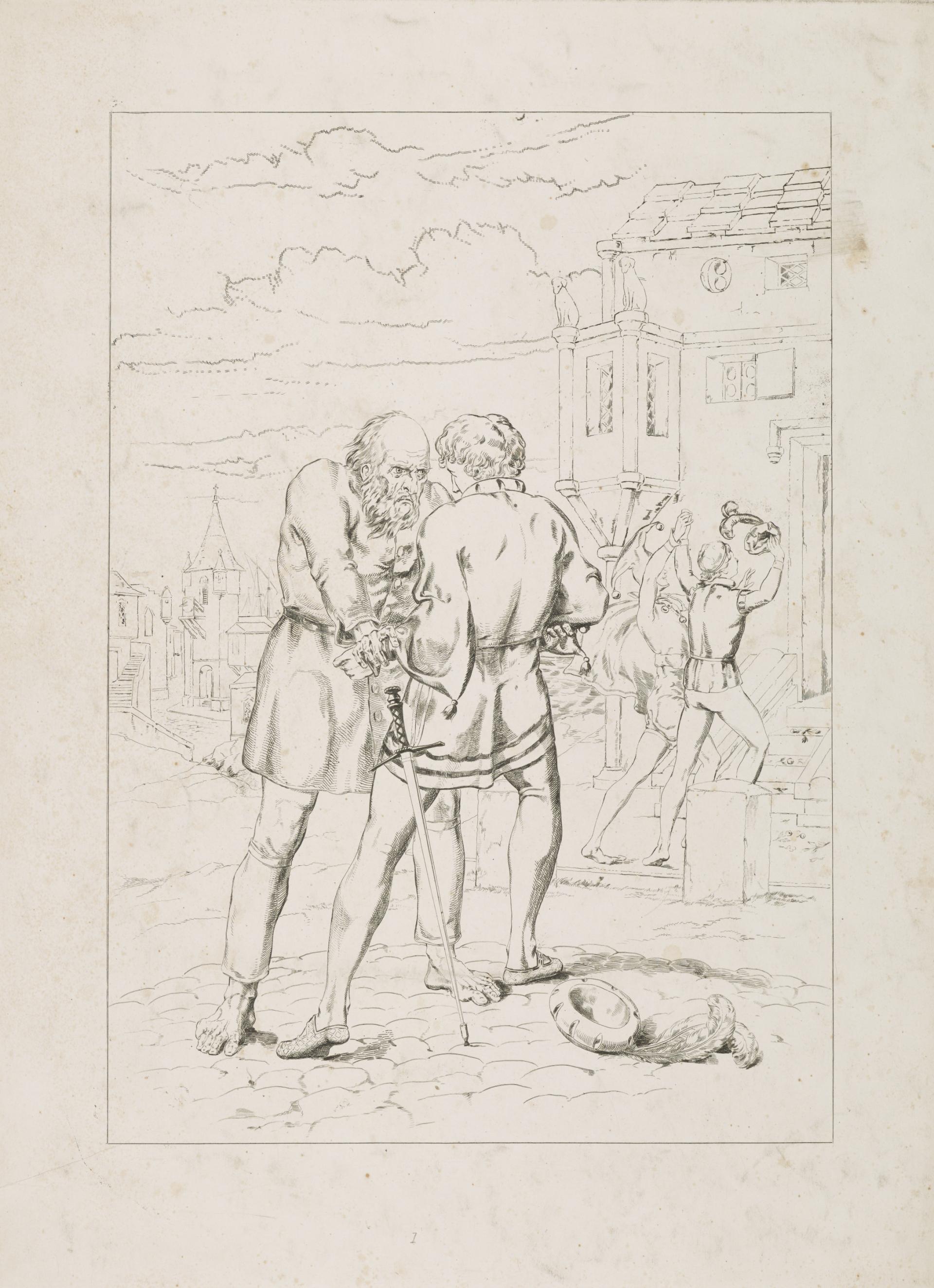

adaptations of the legend written in 1883. - [AF]Amadis_de_Gaula Source: Title Page of Amadís de Gaula (1533), by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo, via Wikimedia Commons.

Amadís de

Gaula is a prose romance composed in Spain or Portugal in the 13th

or 14th century. The story’s protagonist is Amadís, the bravest and most

just of knights, who falls in love with Oriana, the daughter of Lisuarte,

the king of England. Amadís is an orphan who was separated from his English

parents at birth, but through this hardship becomes a better man. Arthurian

in nature, the story is one of chivalry, though more chaste and romanticized

than the Celtic tales of knights it was most likely based on. According to

Romantic Circles, Mary Shelley was reading Robert Southey’s

translation of the poem while writing Frankenstein.

The full text of the 1520

edition printed by Juan Cromberger can be found online at the

National Library of Spain. - [AF]St_George

Source: Title Page of Amadís de Gaula (1533), by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo, via Wikimedia Commons.

Amadís de

Gaula is a prose romance composed in Spain or Portugal in the 13th

or 14th century. The story’s protagonist is Amadís, the bravest and most

just of knights, who falls in love with Oriana, the daughter of Lisuarte,

the king of England. Amadís is an orphan who was separated from his English

parents at birth, but through this hardship becomes a better man. Arthurian

in nature, the story is one of chivalry, though more chaste and romanticized

than the Celtic tales of knights it was most likely based on. According to

Romantic Circles, Mary Shelley was reading Robert Southey’s

translation of the poem while writing Frankenstein.

The full text of the 1520

edition printed by Juan Cromberger can be found online at the

National Library of Spain. - [AF]St_George![A painting on wood panel showing a man wearing armor and riding a rearing gray horse pinning a winged, reptile-like dragon to the ground using a long lance. A woman kneels beyond the man and dragon to our left, and mountains and a city lining a body of water stretch into the deep distance [description drawn from source]. A painting on wood panel showing a man wearing armor and riding a rearing gray horse pinning a winged, reptile-like dragon to the ground using a long lance. A woman kneels beyond the man and dragon to our left, and mountains and a city lining a body of water stretch into the deep distance [description drawn from source].](https://anthologyassetsdev.lib.virginia.edu/shelley-frankenstein-1818/notes/st_george.jpg) Source: Saint George and the Dragon (c. 1432) by Rogier van Der Weyden, from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. St. George, a converted Roman soldier martyred for his newfound Christian

faith, is often depicted slaying a dragon, a symbolic rendering of the

triumph of Christianity over evil. Not only is St. George the patron saint

of England, but by the 14th century, he had been declared both the patron

saint and protector of the royal family. For

more information on St. George, see Reliques of Ancient

English Poetry collected by Thomas Percy and edited by D.L.

Ashliman.

- [AF]Natural_PhilosophyNatural

Philosophy is the study of nature through a philosophical lens. The

two canonical discussions of natural philosophy occur in Aristotle’s On the

Heavens, Meteorology, and On

Generation and Corruption. In the eighteenth century,

natural philosophy was a form of science with an emphasis on scientific

inquiry, but in the Romantic period, it was seen as a method of unifying

physical nature with the spiritual. As Michael Manson and Robert Scott

Stewart point out in Heroes and Hideousness: "Frankenstein" and Failed Unity, natural

philosophy fueled the Romantic idea of the natural world as a giant

organism, in stark contrast to the Enlightenment, which saw the natural

world as more like a mechanical machine. For more information about natural

philosophy and its influence on Frankenstein, see

Patricia Fara’s "Hidden depths: Halley, Hell and Other People" or Rebecca Baumann’s

"Mad

Science." - [AF]Cornelius_Agrippa

Source: Saint George and the Dragon (c. 1432) by Rogier van Der Weyden, from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. St. George, a converted Roman soldier martyred for his newfound Christian

faith, is often depicted slaying a dragon, a symbolic rendering of the

triumph of Christianity over evil. Not only is St. George the patron saint

of England, but by the 14th century, he had been declared both the patron

saint and protector of the royal family. For

more information on St. George, see Reliques of Ancient

English Poetry collected by Thomas Percy and edited by D.L.

Ashliman.

- [AF]Natural_PhilosophyNatural

Philosophy is the study of nature through a philosophical lens. The

two canonical discussions of natural philosophy occur in Aristotle’s On the

Heavens, Meteorology, and On

Generation and Corruption. In the eighteenth century,

natural philosophy was a form of science with an emphasis on scientific

inquiry, but in the Romantic period, it was seen as a method of unifying

physical nature with the spiritual. As Michael Manson and Robert Scott

Stewart point out in Heroes and Hideousness: "Frankenstein" and Failed Unity, natural

philosophy fueled the Romantic idea of the natural world as a giant

organism, in stark contrast to the Enlightenment, which saw the natural

world as more like a mechanical machine. For more information about natural

philosophy and its influence on Frankenstein, see

Patricia Fara’s "Hidden depths: Halley, Hell and Other People" or Rebecca Baumann’s

"Mad

Science." - [AF]Cornelius_Agrippa