The Waste Land

By

T.S. Eliot

Markup by Students and Staff of Marymount University, Greg Gillespie, Tonya Howe, Zafit Olea, Caroline Peloquin

[TP]

THE WASTE LAND

BY

T. S. ELIOT

"Nam Sibyllam quidem Cumis ego ipse oculis meis vidi in ampulla pendere, et cum illi pueri dicerent: Σίβυλλα τί θέλεις; respondebat illa: ἀποθανεῖν θέλω." epigraphepigraphThis is a quote from the first-century Roman prose work Satyricon (c.54-68) believed to be by Gaius Petronius (27-66CE). Eliot translated the epigraph as follows: "I saw with my own eyes the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in a cage, and when the boys said to her: 'Sibyl, what do you want?' she answered: 'I want to die.'" - [TH] NEW YORK

BONI AND LIVERIGHT1922 9 I. THE BURIAL OF THE DEAD 1APRIL is the cruellest monthChaucer, breeding ChaucerThe first line of The Waste Land alludes to the General Prologue of Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, which opens with a "description of Spring characteristic of dream visions of secular love" (Harvard). Chaucer's poem begins, in modern English, as follows: When April with its sweet-smelling showers THas pierced the drought of March to the root, And bathed every vein (of the plants) in such liquid By which power the flower is created; When the West Wind also with its sweet breath In every wood and field has breathed life into The tender new leaves, and the young sun Has run half its course in Aries, And small fowls make melody, Those that sleep all the night with open eyes (So Nature incites them in their hearts), Then folk long to go on pilgrimages, And professional pilgrims to seek foreign shores, To distant shrines, known in various lands.... (General Prologue, 1-14) You might consider how Eliot's version compares to this source text. - [TH] 2Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing 3Memory and desire, stirring 4Dull roots with spring rain. 5Winter kept us warm, covering 6Earth in forgetful snow, feeding 7A little life with dried tubers. 8Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee 9With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade, 10And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten, 10 11And drank coffee, and talked for an hour. 12Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch.identity identity In this passage, the female speaker's statement, "I am not Russian at all; I come from Lithuania, really German," introduces the theme of fragmentation and displacement that permeates the poem. The speaker's identity is shaped by multiple cultural influences, resulting in a fragmented sense of self. She does not fully identify as Russian, Lithuanian, or German, but as a hybrid of all three. This complex identity further highlights the themes of displacement and cultural conflict throughout the work. - [ZO] 13And when we were children, staying at the archduke’s, 14My cousin’s, he took me out on a sled, 15And I was frightened. He said, Marie, 16Marie, hold on tight. And down he went. 17In the mountains, there you feel free. 18I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter. 19What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow 20Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man, 11 21You cannot say, or guess, for you know only 22A heap of broken images, where the sun beats, 23And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, 24And the dry stone no sound of water. Only 25There is shadow under this red rock, 26(Come in under the shadow of this red rock), 27And I will show you something different from either 28Your shadow at morning striding behind you 29Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you; 12 30I will show you fear in a handful of dust. 31FrischWagner weht der Wind 32Der-Heimat zu 33Mein Irisch Kind, 34Wo weilest du? Wagner These lines are quoted from Richard Wagner's Tristan und

Isolde (1865), a German opera based on a 12th century chivalric tragic

poem Tristan and Iseult. There are multiple different

versions of the story, but at root, it is a Celtic legend about tragic love; the

knight Tristan has been tasked with accompanying the Irish maiden Iseult to be

married to his uncle, the King of Cornwall. On the way, Tristan and Iseult fall

deeply in love, which causes many tempestuous problems. The story became very

popular in the ninteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially among the

Pre-Raphaelites, a group of artists and writers influenced by Romanticism who

sought inspiration in Italian Renaissance art and medieval courtly themes. The

image included here, by the Pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse, is Tristan and Isolde with the Potion (1916), via Wikimedia Commons. Tristan and Iseult are on the ship heading for

Cornwall and Iseult's marriage; they are drinking a love potion. The lines are

from the first act of Tristan und Isolde, and are sung by

an anonymous sailor about his lover, left behind in Ireland. Translated, the lines

read "Fresh blows the wind / homeward: / my Irish maid, / where do you linger?" A

later line (42, below) from the same opera, "Empty and desolate is the sea,"

sandwiches Eliot's description of the first meeting between the "hyacinth girl"

(36) and her lover, who remembers being struck by her and feeling "neither /

Living nor dead" (39-40). ( - [TH]

35“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

36“They called me the hyacinth girl."

37—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden,

38Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

39Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

40Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

41Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

13

42Oed’ und leer das Meer.

43Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyanteclairvoyant,

clairvoyant

This noun comes from the word "clairvoyance", which in the French means

clear-sighted. A clairvoyant is what we would now call a psychic, someone

who can see things that are not physically there. Madame Sosostris is a

fortune teller who has a reputation as "the wisest woman in Europe." The -e

is added to the word clairvoyant to make it feminine in the French (OED).

- [CP]

44Had a bad cold, nevertheless

45Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe,

46With a wicked pack of

cardscardscardsA character in Eliot's poem visits a famous fortune

teller, and the following lines describe the tarot cards she received at a

reading. According to Elizabeth DeBold of the Folger Shakespeare Library, tarot originated in 14th-century

Egypt, and traveled to Europe during the Renaissance. - [TH]. Here, said

she,

47Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

48(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

49Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

50The lady of situations.

51Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

14

52And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

53Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

54Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

55The Hanged Man. Fear death by

waterwater.

water

Water is a prevalent motif throughout The Waste

Land. Water is often associated with regeneration/rebirth, but here and

elsewhere, it is associated with death.

- [CP]

56I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring.

57Thank you. If you see dear Mrs. Equitone,

58Tell her I bring the horoscope myself:

59One must be so careful these days.

60Unreal City,

61Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

15

62A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

63I had not thought death had undone so many.

64Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

65And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

66Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

67To where Saint Mary

Woolnothwoolnothwoolnoth

These lines are quoted from Richard Wagner's Tristan und

Isolde (1865), a German opera based on a 12th century chivalric tragic

poem Tristan and Iseult. There are multiple different

versions of the story, but at root, it is a Celtic legend about tragic love; the

knight Tristan has been tasked with accompanying the Irish maiden Iseult to be

married to his uncle, the King of Cornwall. On the way, Tristan and Iseult fall

deeply in love, which causes many tempestuous problems. The story became very

popular in the ninteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially among the

Pre-Raphaelites, a group of artists and writers influenced by Romanticism who

sought inspiration in Italian Renaissance art and medieval courtly themes. The

image included here, by the Pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse, is Tristan and Isolde with the Potion (1916), via Wikimedia Commons. Tristan and Iseult are on the ship heading for

Cornwall and Iseult's marriage; they are drinking a love potion. The lines are

from the first act of Tristan und Isolde, and are sung by

an anonymous sailor about his lover, left behind in Ireland. Translated, the lines

read "Fresh blows the wind / homeward: / my Irish maid, / where do you linger?" A

later line (42, below) from the same opera, "Empty and desolate is the sea,"

sandwiches Eliot's description of the first meeting between the "hyacinth girl"

(36) and her lover, who remembers being struck by her and feeling "neither /

Living nor dead" (39-40). ( - [TH]

35“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

36“They called me the hyacinth girl."

37—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden,

38Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

39Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

40Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

41Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

13

42Oed’ und leer das Meer.

43Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyanteclairvoyant,

clairvoyant

This noun comes from the word "clairvoyance", which in the French means

clear-sighted. A clairvoyant is what we would now call a psychic, someone

who can see things that are not physically there. Madame Sosostris is a

fortune teller who has a reputation as "the wisest woman in Europe." The -e

is added to the word clairvoyant to make it feminine in the French (OED).

- [CP]

44Had a bad cold, nevertheless

45Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe,

46With a wicked pack of

cardscardscardsA character in Eliot's poem visits a famous fortune

teller, and the following lines describe the tarot cards she received at a

reading. According to Elizabeth DeBold of the Folger Shakespeare Library, tarot originated in 14th-century

Egypt, and traveled to Europe during the Renaissance. - [TH]. Here, said

she,

47Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

48(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

49Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

50The lady of situations.

51Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

14

52And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

53Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

54Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

55The Hanged Man. Fear death by

waterwater.

water

Water is a prevalent motif throughout The Waste

Land. Water is often associated with regeneration/rebirth, but here and

elsewhere, it is associated with death.

- [CP]

56I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring.

57Thank you. If you see dear Mrs. Equitone,

58Tell her I bring the horoscope myself:

59One must be so careful these days.

60Unreal City,

61Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

15

62A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

63I had not thought death had undone so many.

64Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

65And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

66Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

67To where Saint Mary

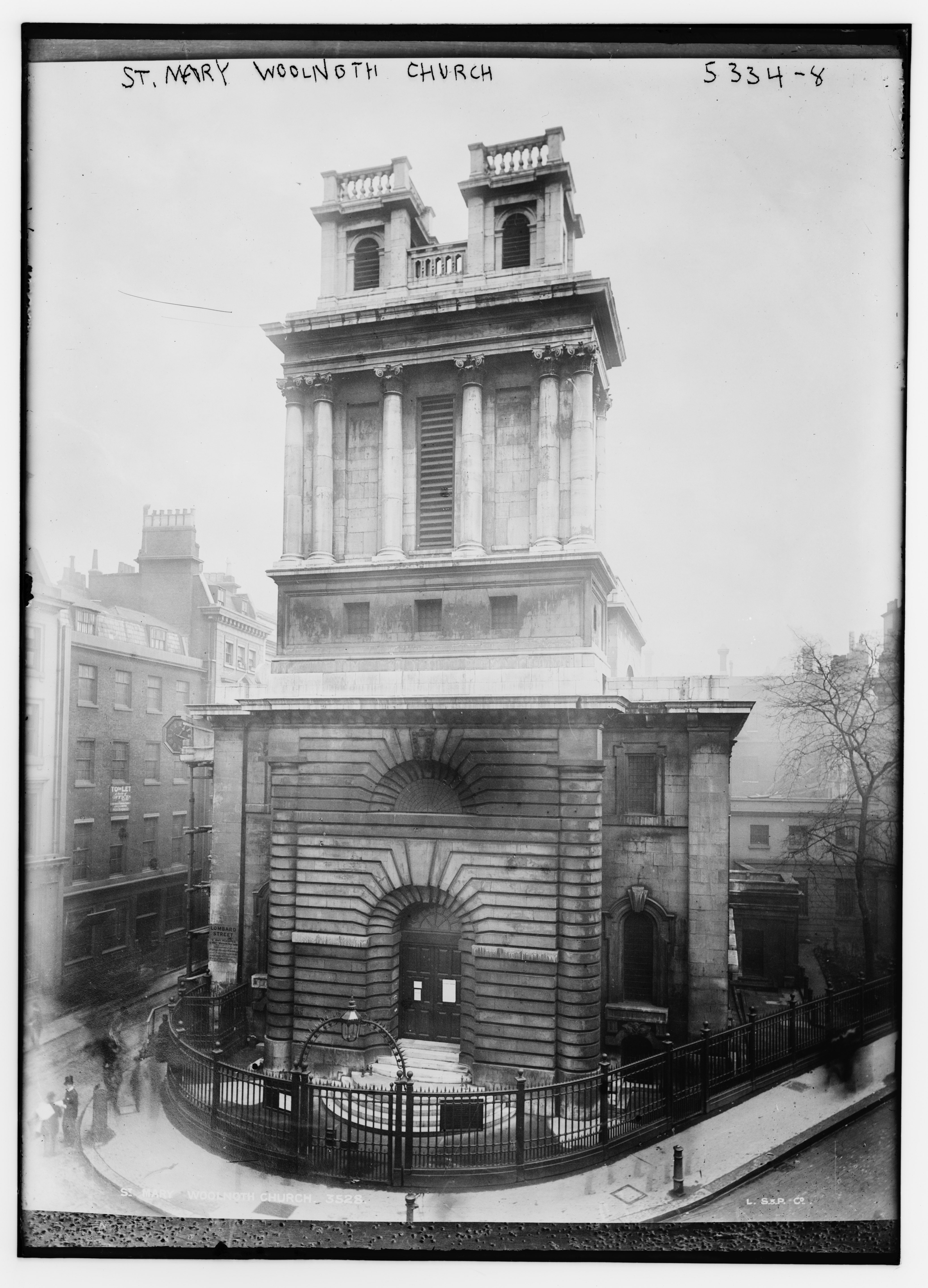

Woolnothwoolnothwoolnoth Saint Mary

Woolnoth is an Anglican church in London, first built in the 12th century,

then rebuilt on several occasions. The photograph included here, from about

1900, originally from the Library of Congress, shows the church in its

modern form, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoore and opened in 1727. This is

likely very close to what Eliot would have seen. It is possible that the

site had been a place of worship for 2000 years (Wikipedia).

- [TH] kept the hours

68With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

69There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: “Stetson!

70“You who were with me in the ships at MylaemylaemylaeThe Battle of

Mylae, a naval battle won in 260BCE by Roman naval

forces. - [TH]!

17

71“That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

72“Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

73“Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

74“O keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

75“Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!

76“You!

hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!baudelairebaudelaireThis is an allusion to the last line of Charles

Baudelaire's introductory poem "Au Lecteur [To the Reader]" from his

collection Fleurs du mal [Flowers of Evil

(1857-1868). The line reads, "Hypocritical reader, --my twin, --my

brother!" You can read Baudelaire's poems online. - [TH]"

16

II. A GAME OF CHESS

77The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,

78Glowed on the marble, where the glass

79Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines

80From which a golden Cupidoncupidon peeped out

cupidon

Saint Mary

Woolnoth is an Anglican church in London, first built in the 12th century,

then rebuilt on several occasions. The photograph included here, from about

1900, originally from the Library of Congress, shows the church in its

modern form, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoore and opened in 1727. This is

likely very close to what Eliot would have seen. It is possible that the

site had been a place of worship for 2000 years (Wikipedia).

- [TH] kept the hours

68With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

69There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: “Stetson!

70“You who were with me in the ships at MylaemylaemylaeThe Battle of

Mylae, a naval battle won in 260BCE by Roman naval

forces. - [TH]!

17

71“That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

72“Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

73“Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

74“O keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

75“Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!

76“You!

hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!baudelairebaudelaireThis is an allusion to the last line of Charles

Baudelaire's introductory poem "Au Lecteur [To the Reader]" from his

collection Fleurs du mal [Flowers of Evil

(1857-1868). The line reads, "Hypocritical reader, --my twin, --my

brother!" You can read Baudelaire's poems online. - [TH]"

16

II. A GAME OF CHESS

77The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,

78Glowed on the marble, where the glass

79Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines

80From which a golden Cupidoncupidon peeped out

cupidon

The scene

described by the speaker features banners adorned with fruit-bearing vines

and a standard depicting a golden "Cupidon," an alternate name for the Roman

god of love, Cupid. The use of Cupidon in this context evokes themes of

desire, fertility, and the pursuit of romantic love. The image of Cupidon

peeking out from behind the banner may also imply a sense of voyeurism or

hidden desire, contributing to an undercurrent of sexual tension in the

scene. This lush, sensual imagery is suggestive of the speaker's heightened

sensibility, and highlights the poem's themes of passion and desire. The

image included here, via Wikipedia, shows a Roman copy of an original Greek sculpture of

Eros Stringing His Bow.

- [ZO]

81(Another hid his eyes behind his wing)

82Doubled the flames of sevenbranched candelabra

83Reflecting light upon the table as

84The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it,

85From satin cases poured in rich profusion.

18

86In vials of ivory and coloured glass

87Unstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfumes,

88Unguent, powdered, or liquid—troubled, confused

89And drowned the sense in odours; stirred by the air

90That freshened from the window, these ascended

91In fattening the prolonged candle-flames,

92Flung their smoke into the laquearia,

93Stirring the pattern on the coffered ceiling.

94Huge sea-wood fed with copper

95Burned green and orange, framed by the coloured stone,

96In which sad light a carvèd dolphin swam.

19

97Above the antique mantel was displayed

98As though a window gave upon the sylvan scene

99The change of PhilomelphilomelphilomelAn allusion to the ancient Greek story of Philomela,

which was recounted in Ovid's Metamorphoses 6.412-674. In the story, Tereus, King of

Thrace, marries the Athenian Procne. Procne asks her husband to bring her

sister, Philomela, to visit her in Thrace. Tereus rapes Philomela, and to

keep her from telling her sister of the assault, he cuts out her tongue.

Philomela communicates her story to Procne by weaving a tapestry showing the

events. The two sisters avenge the abuse by killing Itys, Procne and Tereus'

son, and baking him into a pie which Tereus eats. The women flee, pursued by

Tereus; the gods transform the three into birds--Philomela becomes the

sweet-singing nightingale. - [TH], by the barbarous king

100So rudely forced; yet there the nightingale

101Filled all the desert with inviolable voice

102And still she cried, and still the world pursues,

103“Jug Jug" to dirty ears.

104And other withered stumps of time

105Were told upon the walls; staring forms

106Leaned out, leaning, hushing the room enclosed.

107Footsteps shuffled on the stair.

20

108Under the firelight, under the brush, her hair

109Spread out in fiery points

110Glowed into words, then would be savagely still.

111“My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

112“Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

113“What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

114“I never know what you are thinking. Think."

115I think we are in rats’ alley

116Where the dead men lost their bones.

21

117“What is that noise?"

118The wind under the door.

119“What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?"

120Nothing again nothing.

121 “Do

122“You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember

123“Nothing?"

124I remember

125Those are pearls that were his

eyes.pearlspearlsThroughout The Waste Land,

Eliot refers to Shakespeare's The Tempest. This is an allusion to I.ii.394-398, when

Ariel sings about a drowned man undergoing "a sea-change / Into something

rich and strange." The words suggest the fate of Ferdinand's father, whom he

believes lost at sea. - [TH]

126“Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?"

127But

128O O O O that Shakespeherian

Ragrag—

ragThough Eliot

has made changes to the language, That Shakespearian Rag is

a ragtime tune from 1912 (Parker, "Songs in T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land"). Ragtime was a projenitor

of jazz, the rhythms of which influenced Eliot's style. - [TH]

129It’s so elegant

130So intelligent

22

131“What shall I do now? What shall I do?"

132I shall rush out as I am, and walk the street

133“With my hair down, so. What shall we do tomorrow?

134“What shall we ever do?"

135The hot w[a]ter at ten.

136And if it rains, a closed car at four.

137And we shall play a game of chess,

138Pressing lidless eyes and waiting for a knock upon the door.

139When Lil’s husband got demobbeddemobbeddemobbedColloquial British expression for "demobilized,"

specifically, released from military service. Lil's husband likely served in

World War I (1914-1918). - [TH], I said—

23

140 I didn’t mince my words, I said to her myself,

141HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIMEhurryhurryThe

barkeep is informing the patrons of closing time. - [TH]

142Now Albert’s coming back, make yourself a bit smart.

143He’ll want to know what you done with that money he gave you

144To get yourself some teeth. He did, I was there.

145You have them all out, Lil, and get a nice set,

146He said, I swear, I can’t bear to look at you.

147And no more can’t I, I said, and think of poor Albert,

148He’s been in the army four years, he wants a good time,

24

149And if you don’t give it him, there’s others will, I said.

150Oh is there, she said. Something o’ that, I said.

151Then I’ll know who to thank, she said, and give me a straight look.

152HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIME

153If you don’t like it you can get on with it, I said.

154Others can pick and choose if you can’t.

155But if Albert makes off, it won’t be for lack of telling.

156You ought to be ashamed, I said, to look so antique.

157(And her only thirty-one.)

158I can’t help it, she said, pulling a long face,

25

159It’s them pillspillspillsThe speaker

is referring to medication that induces abortion. - [TH] I took, to bring it

off, she said.

160(She’s had five already, and nearly died of young George.)

161The chemist said it would be all right, but I’ve never been the same.

162You are a proper fool, I said.

163Well, if Albert won’t leave you alone, there it is, I said,

164What you get married for if you don’t want children?

165HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIME

166Well, that Sunday Albert was home, they had a hot gammon,

167And they asked me in to dinner, to get the beauty of it hot—

26

168HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIME

169HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIME

170Goonight Bill. Goonight Lou. Goonight May. Goonight.

171Ta ta. Goonight. Goonight.

172Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.

27

III. THE FIRE SERMON

173THE river’s tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf

174Clutch and sink into the wet bank. The wind

175Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed.

176Sweet Thames, run

softly, till I end my song.

177The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers,

178Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends

179Or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed.

28

180And their friends, the loitering heirs of city directors;

181Departed, have left no addresses.

182By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept . . .

183Sweet Thames, run softly till

I end my song,spenserspenserAn allusion to Edmund Spenser's poem "Prothalamion" (1596), which celebrates the marriage of two

"nymphs." Nymphs are female water spirits of classical myth, but the word

also suggests young women in general. A prothalamion is a type of poem that

celebrates a coming marriage. - [TH]

184Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long.

185But at my back in a cold blast I hear

186The rattle of the bones, and chuckle spread from ear to ear.

187A rat crept softly through the vegetation

188Dragging its slimy belly on the bank

189While I was fishing in the dull canal

29

190On a winter evening round behind the gashouse

191Musing upon the king my brother’s wreck

192And on the king my father’s death before him.

193White bodies naked on the low damp ground

194And bones cast in a little low dry garret,

195Rattled by the rat’s foot only, year to year.

196But at my back from time to time I hear

197The sound of horns and motors, which shall bring

198Sweeney to Mrs. Porter in the spring.

199O the moon shone bright on Mrs. Porter

200And on her daughter

30

201They wash their feet in soda water

202Et O ces

voix d’enfants, chantant dans la coupole!Verlaine

Verlaine

In this line, the speaker directly

alludes to the last line of the French poet Paul Verlaine’s sonnet

"Parsifal": "And, O those children's voices singing in the dome!" The sonnet

is a meditation on art and the power of music; it reflects the poet's

response to hearing Richard Wagner's opera Parsifal, which is a

major intertext to Eliot's poem. The use of this allusion adds an extra

layer of meaning to the poem. The inclusion of French in the midst of an

English poem could also suggest a sense of cultural dislocation or

separation. Additionally, the image of children's voices singing in a dome

may represent a symbol of purity and innocence that contrasts with the

themes of corruption and decay present elsewhere in the poem. To learn more

about Verlaine, see the Poetry

Foundation. To learn more about Wagner's role in "The Waste Land,"

see this scholarly essay by Philip Waldron, "The Music of Poetry:

Wagner in The Waste Land.". You can read

Verlaine's poem in the original French and in English translation here.

- [ZO]

203Twit twit twit

204Jug jug jug jug jug jug

205So rudely forc’d.

206Tereu

207Unreal City

208Under the brown fog of a winter noon

209Mr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant

210Unshaven, with a pocket full of currants

211C.i.f. London: documents at sight,

212Asked me in demotic French

213To luncheon at the Cannon Street Hotel

31

214Followed by a weekend at the Metropole.

215At the violet hour, when the eyes and back

216Turn upward from the desk, when the human engine waits

217Like a taxi throbbing waiting,

218I TiresiastiresiastiresiasIn Greek mythology, Tiresias is a blind prophet who also lived as both a

man and a woman. He was instrumental in the action of Sophocles' Oedipus

plays, and he also appeared in Homer's Odyssey. - [TH], though blind, throbbing between two lives,

219Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see

200At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives

221Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,

222The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

32

223Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

224Out of the window perilously spread

225Her drying combinations touched by the sun’s last rays,

226On the divan are piled (at night her bed)

227Stockings, slippers, camisoles, and stays.

228I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

229Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest—

230I too awaited the expected guest.

231He, the young man carbuncularcarbuncular, arrives,

carbuncular

Used here as an adjective, "carbuncular" comes from the word "carbuncle,"

which is an lesion on the skin that is irritated and filled with pus, and

overall is unpleasant to look at (OED n3).

- [CP]

232A small house agent’s clerk, with one bold stare,

233One of the low on whom assurance sits

234As a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire.

235The time is now propitious, as he guesses,

236The meal is ended, she is bored and tired,

33

237Endeavours to engage her in caresses

238Which still are unreproved, if undesired.

239Flushed and decided, he assaults at once;

240Exploring hands encounter no defence;

241His vanity requires no response,

242And makes a welcome of indifference.

243(And I Tiresias have foresuffered all

244Enacted on this same divan or bed;

245I who have sat by Thebes below the wall

246And walked among the lowest of the dead.)

247Bestows one final patronising kiss,

248And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit . . .

249She turns and looks a moment in the glass,

250Hardly aware of her departed lover;

34

251Her brain allows one half-formed thought to pass:

252“Well now that’s done: and I’m glad it’s over."

253When lovely woman stoops to folly and

254Paces about her room again, alone,

255She smooths her hair with automatic hand,

256And puts a record on the gramophone.

257“This music crept by me upon the waters"

258And along the Strand, up Queen Victoria Street.

259O City city, I can sometimes hear

260Beside a public bar in Lower Thames Street,

35

261The pleasant whining of a mandoline

262And a clatter and a chatter from within

263Where fishmen lounge at noon: where the walls

264Of Magnus Martyr hold

265Inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold.

266The river sweats

267Oil and tar

268The barges drift

269With the turning tide

270Red sails

271Wide

272To leeward, swing on the heavy spar.

273The barges wash

36

274Drifting logs

275Down Greenwich

reach

276Past the Isle of

Dogs.

277Weialala leia

278Wallala leialala

279Elizabeth and Leicester

280Beating oars

281The stern was formed

282A gilded shell

283Red and gold

284The brisk swell

285Rippled both shores

286Southwest wind

287Carried down stream

288The peal of bells

289White towers

37

290Weialala leia

291Wallala leialala

292“Trams and dusty trees.

293Highbury bore me.

Richmond and Kew

294Undid me. By Richmond I raised my knees

295Supine on the floor of a narrow canoe."

296“My feet are at MoorgateMoorgate, and my heart

Moorgate

The scene

described by the speaker features banners adorned with fruit-bearing vines

and a standard depicting a golden "Cupidon," an alternate name for the Roman

god of love, Cupid. The use of Cupidon in this context evokes themes of

desire, fertility, and the pursuit of romantic love. The image of Cupidon

peeking out from behind the banner may also imply a sense of voyeurism or

hidden desire, contributing to an undercurrent of sexual tension in the

scene. This lush, sensual imagery is suggestive of the speaker's heightened

sensibility, and highlights the poem's themes of passion and desire. The

image included here, via Wikipedia, shows a Roman copy of an original Greek sculpture of

Eros Stringing His Bow.

- [ZO]

81(Another hid his eyes behind his wing)

82Doubled the flames of sevenbranched candelabra

83Reflecting light upon the table as

84The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it,

85From satin cases poured in rich profusion.

18

86In vials of ivory and coloured glass

87Unstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfumes,

88Unguent, powdered, or liquid—troubled, confused

89And drowned the sense in odours; stirred by the air

90That freshened from the window, these ascended

91In fattening the prolonged candle-flames,

92Flung their smoke into the laquearia,

93Stirring the pattern on the coffered ceiling.

94Huge sea-wood fed with copper

95Burned green and orange, framed by the coloured stone,

96In which sad light a carvèd dolphin swam.

19

97Above the antique mantel was displayed

98As though a window gave upon the sylvan scene

99The change of PhilomelphilomelphilomelAn allusion to the ancient Greek story of Philomela,

which was recounted in Ovid's Metamorphoses 6.412-674. In the story, Tereus, King of

Thrace, marries the Athenian Procne. Procne asks her husband to bring her

sister, Philomela, to visit her in Thrace. Tereus rapes Philomela, and to

keep her from telling her sister of the assault, he cuts out her tongue.

Philomela communicates her story to Procne by weaving a tapestry showing the

events. The two sisters avenge the abuse by killing Itys, Procne and Tereus'

son, and baking him into a pie which Tereus eats. The women flee, pursued by

Tereus; the gods transform the three into birds--Philomela becomes the

sweet-singing nightingale. - [TH], by the barbarous king

100So rudely forced; yet there the nightingale

101Filled all the desert with inviolable voice

102And still she cried, and still the world pursues,

103“Jug Jug" to dirty ears.

104And other withered stumps of time

105Were told upon the walls; staring forms

106Leaned out, leaning, hushing the room enclosed.

107Footsteps shuffled on the stair.

20

108Under the firelight, under the brush, her hair

109Spread out in fiery points

110Glowed into words, then would be savagely still.

111“My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

112“Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

113“What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

114“I never know what you are thinking. Think."

115I think we are in rats’ alley

116Where the dead men lost their bones.

21

117“What is that noise?"

118The wind under the door.

119“What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?"

120Nothing again nothing.

121 “Do

122“You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember

123“Nothing?"

124I remember

125Those are pearls that were his

eyes.pearlspearlsThroughout The Waste Land,

Eliot refers to Shakespeare's The Tempest. This is an allusion to I.ii.394-398, when

Ariel sings about a drowned man undergoing "a sea-change / Into something

rich and strange." The words suggest the fate of Ferdinand's father, whom he

believes lost at sea. - [TH]

126“Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?"

127But

128O O O O that Shakespeherian

Ragrag—

ragThough Eliot

has made changes to the language, That Shakespearian Rag is

a ragtime tune from 1912 (Parker, "Songs in T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land"). Ragtime was a projenitor

of jazz, the rhythms of which influenced Eliot's style. - [TH]

129It’s so elegant

130So intelligent

22

131“What shall I do now? What shall I do?"

132I shall rush out as I am, and walk the street

133“With my hair down, so. What shall we do tomorrow?

134“What shall we ever do?"

135The hot w[a]ter at ten.

136And if it rains, a closed car at four.

137And we shall play a game of chess,

138Pressing lidless eyes and waiting for a knock upon the door.

139When Lil’s husband got demobbeddemobbeddemobbedColloquial British expression for "demobilized,"

specifically, released from military service. Lil's husband likely served in

World War I (1914-1918). - [TH], I said—

23

140 I didn’t mince my words, I said to her myself,

141HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIMEhurryhurryThe

barkeep is informing the patrons of closing time. - [TH]

142Now Albert’s coming back, make yourself a bit smart.

143He’ll want to know what you done with that money he gave you

144To get yourself some teeth. He did, I was there.

145You have them all out, Lil, and get a nice set,

146He said, I swear, I can’t bear to look at you.

147And no more can’t I, I said, and think of poor Albert,

148He’s been in the army four years, he wants a good time,

24

149And if you don’t give it him, there’s others will, I said.

150Oh is there, she said. Something o’ that, I said.

151Then I’ll know who to thank, she said, and give me a straight look.

152HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIME

153If you don’t like it you can get on with it, I said.

154Others can pick and choose if you can’t.

155But if Albert makes off, it won’t be for lack of telling.

156You ought to be ashamed, I said, to look so antique.

157(And her only thirty-one.)

158I can’t help it, she said, pulling a long face,

25

159It’s them pillspillspillsThe speaker

is referring to medication that induces abortion. - [TH] I took, to bring it

off, she said.

160(She’s had five already, and nearly died of young George.)

161The chemist said it would be all right, but I’ve never been the same.

162You are a proper fool, I said.

163Well, if Albert won’t leave you alone, there it is, I said,

164What you get married for if you don’t want children?

165HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIME

166Well, that Sunday Albert was home, they had a hot gammon,

167And they asked me in to dinner, to get the beauty of it hot—

26

168HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIME

169HURRY UP PLEASE IT’S TIME

170Goonight Bill. Goonight Lou. Goonight May. Goonight.

171Ta ta. Goonight. Goonight.

172Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.

27

III. THE FIRE SERMON

173THE river’s tent is broken: the last fingers of leaf

174Clutch and sink into the wet bank. The wind

175Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed.

176Sweet Thames, run

softly, till I end my song.

177The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers,

178Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends

179Or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed.

28

180And their friends, the loitering heirs of city directors;

181Departed, have left no addresses.

182By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept . . .

183Sweet Thames, run softly till

I end my song,spenserspenserAn allusion to Edmund Spenser's poem "Prothalamion" (1596), which celebrates the marriage of two

"nymphs." Nymphs are female water spirits of classical myth, but the word

also suggests young women in general. A prothalamion is a type of poem that

celebrates a coming marriage. - [TH]

184Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long.

185But at my back in a cold blast I hear

186The rattle of the bones, and chuckle spread from ear to ear.

187A rat crept softly through the vegetation

188Dragging its slimy belly on the bank

189While I was fishing in the dull canal

29

190On a winter evening round behind the gashouse

191Musing upon the king my brother’s wreck

192And on the king my father’s death before him.

193White bodies naked on the low damp ground

194And bones cast in a little low dry garret,

195Rattled by the rat’s foot only, year to year.

196But at my back from time to time I hear

197The sound of horns and motors, which shall bring

198Sweeney to Mrs. Porter in the spring.

199O the moon shone bright on Mrs. Porter

200And on her daughter

30

201They wash their feet in soda water

202Et O ces

voix d’enfants, chantant dans la coupole!Verlaine

Verlaine

In this line, the speaker directly

alludes to the last line of the French poet Paul Verlaine’s sonnet

"Parsifal": "And, O those children's voices singing in the dome!" The sonnet

is a meditation on art and the power of music; it reflects the poet's

response to hearing Richard Wagner's opera Parsifal, which is a

major intertext to Eliot's poem. The use of this allusion adds an extra

layer of meaning to the poem. The inclusion of French in the midst of an

English poem could also suggest a sense of cultural dislocation or

separation. Additionally, the image of children's voices singing in a dome

may represent a symbol of purity and innocence that contrasts with the

themes of corruption and decay present elsewhere in the poem. To learn more

about Verlaine, see the Poetry

Foundation. To learn more about Wagner's role in "The Waste Land,"

see this scholarly essay by Philip Waldron, "The Music of Poetry:

Wagner in The Waste Land.". You can read

Verlaine's poem in the original French and in English translation here.

- [ZO]

203Twit twit twit

204Jug jug jug jug jug jug

205So rudely forc’d.

206Tereu

207Unreal City

208Under the brown fog of a winter noon

209Mr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant

210Unshaven, with a pocket full of currants

211C.i.f. London: documents at sight,

212Asked me in demotic French

213To luncheon at the Cannon Street Hotel

31

214Followed by a weekend at the Metropole.

215At the violet hour, when the eyes and back

216Turn upward from the desk, when the human engine waits

217Like a taxi throbbing waiting,

218I TiresiastiresiastiresiasIn Greek mythology, Tiresias is a blind prophet who also lived as both a

man and a woman. He was instrumental in the action of Sophocles' Oedipus

plays, and he also appeared in Homer's Odyssey. - [TH], though blind, throbbing between two lives,

219Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see

200At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives

221Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,

222The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

32

223Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

224Out of the window perilously spread

225Her drying combinations touched by the sun’s last rays,

226On the divan are piled (at night her bed)

227Stockings, slippers, camisoles, and stays.

228I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

229Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest—

230I too awaited the expected guest.

231He, the young man carbuncularcarbuncular, arrives,

carbuncular

Used here as an adjective, "carbuncular" comes from the word "carbuncle,"

which is an lesion on the skin that is irritated and filled with pus, and

overall is unpleasant to look at (OED n3).

- [CP]

232A small house agent’s clerk, with one bold stare,

233One of the low on whom assurance sits

234As a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire.

235The time is now propitious, as he guesses,

236The meal is ended, she is bored and tired,

33

237Endeavours to engage her in caresses

238Which still are unreproved, if undesired.

239Flushed and decided, he assaults at once;

240Exploring hands encounter no defence;

241His vanity requires no response,

242And makes a welcome of indifference.

243(And I Tiresias have foresuffered all

244Enacted on this same divan or bed;

245I who have sat by Thebes below the wall

246And walked among the lowest of the dead.)

247Bestows one final patronising kiss,

248And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit . . .

249She turns and looks a moment in the glass,

250Hardly aware of her departed lover;

34

251Her brain allows one half-formed thought to pass:

252“Well now that’s done: and I’m glad it’s over."

253When lovely woman stoops to folly and

254Paces about her room again, alone,

255She smooths her hair with automatic hand,

256And puts a record on the gramophone.

257“This music crept by me upon the waters"

258And along the Strand, up Queen Victoria Street.

259O City city, I can sometimes hear

260Beside a public bar in Lower Thames Street,

35

261The pleasant whining of a mandoline

262And a clatter and a chatter from within

263Where fishmen lounge at noon: where the walls

264Of Magnus Martyr hold

265Inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold.

266The river sweats

267Oil and tar

268The barges drift

269With the turning tide

270Red sails

271Wide

272To leeward, swing on the heavy spar.

273The barges wash

36

274Drifting logs

275Down Greenwich

reach

276Past the Isle of

Dogs.

277Weialala leia

278Wallala leialala

279Elizabeth and Leicester

280Beating oars

281The stern was formed

282A gilded shell

283Red and gold

284The brisk swell

285Rippled both shores

286Southwest wind

287Carried down stream

288The peal of bells

289White towers

37

290Weialala leia

291Wallala leialala

292“Trams and dusty trees.

293Highbury bore me.

Richmond and Kew

294Undid me. By Richmond I raised my knees

295Supine on the floor of a narrow canoe."

296“My feet are at MoorgateMoorgate, and my heart

Moorgate

Dating back to the Medieval period,

Moorgate was the last of the old gates to be built in the Roman defense wall

that surrounded the fort of Londinium, now London. The original Roman walls

were built 100-400 CE, but Moorgate was originally a secondary gate that was

expanded in 1415. It led to the marshy Moorfields area in the north of

London. It was demolished in 1762. To learn more about the London Wall, see

Wikipedia. The image here, also via Wikipedia, shows an

18th-century engraving depicting Moorgate before it was demolished.

- [CP]

297Under my feet. After the event

298He wept. He promised ‘a new start’.

299I made no comment. What should I resent?"

300“On Margate Sands.

301I can connect

302Nothing with nothing.

38

303The broken fingernails of dirty hands.

304My people humble people who expect

305Nothing."

306la la

307To CarthageCarthage then I came

Carthage

Dating back to the Medieval period,

Moorgate was the last of the old gates to be built in the Roman defense wall

that surrounded the fort of Londinium, now London. The original Roman walls

were built 100-400 CE, but Moorgate was originally a secondary gate that was

expanded in 1415. It led to the marshy Moorfields area in the north of

London. It was demolished in 1762. To learn more about the London Wall, see

Wikipedia. The image here, also via Wikipedia, shows an

18th-century engraving depicting Moorgate before it was demolished.

- [CP]

297Under my feet. After the event

298He wept. He promised ‘a new start’.

299I made no comment. What should I resent?"

300“On Margate Sands.

301I can connect

302Nothing with nothing.

38

303The broken fingernails of dirty hands.

304My people humble people who expect

305Nothing."

306la la

307To CarthageCarthage then I came

Carthage

This is a reference to the ancient city of Carthage, which was located in

what is now Tunisia. Carthage was a major center of trade and civilization

in the ancient Mediterranean world, but it was destroyed by the Romans in

the Punic Wars in the 2nd century BCE. The use of Carthage in the poem may

suggest themes of destruction, decay, and the decline of civilization. The

city of Carthage has been interpreted as a symbol of the failure and fall of

human civilizations, which can serve as a warning for modern society. The

image included in this annotation, via Wikimedia Commons, shows

a representation of the ancient city from the Carthage National Museum in

Tunisia.

- [ZO]

308Burning burning burning burning

309O Lord Thou pluckest me out

310O Lord Thou pluckest

311burning

39

IV. DEATH BY WATER

312PHLEBAS the Phoenician, a fortnight dead,

313Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep sea swell

314And the profit and loss.

315A current under sea

316Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell

317He passed the stages of his age and youth

318Entering the whirlpool.

319Gentile or Jew

320O you who turn the wheel and look to windward,

321Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

40

V. WHAT THE THUNDER SAID

322AFTER the torchlight red on sweaty faces

323After the frosty silence in the gardens

324After the agony in stony places

325The shouting and the crying

326Prison and palace and reverberation

327Of thunder of spring over distant mountains

328He who was living is now dead

329We who were living are now dying

330With a little patience

41

331Here is no water but only rock

332Rock and no water and the sandy road

333The road winding above among the mountains

334Which are mountains of rock without water

335If there were water we should stop and drink

336Amongst the rock one cannot stop or think

337Sweat is dry and feet are in the sand

338If there were only water amongst the rock

339Dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit

340Here one can neither stand nor lie nor sit

341There is not even silence in the mountains

42

342But dry sterile thunder without rain

343There is not even solitude in the mountains

344But red sullen faces sneer and snarl

345From doors of mudcracked houses

346If there were water

346And no rock

347If there were rock

348And also water

349And water

350A spring

351A pool among the rock

352If there were the sound of water only

353Not the cicada

354And dry grass singing

355But sound of water over a rock

43

356Where the hermit-thrush sings in the pine trees

357Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop

358But there is no water

359Who is the third who walks always beside you?

360When I count, there are only you and I together

361But when I look ahead up the white road

362There is always another one walking beside you

363Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

364 I do not know whether a man or a woman

365—But who is that on the other side of you?

44

366What is that sound high in the air

367Murmur of maternal lamentation

368Who are those hooded hordes swarming

369Over endless plains, stumbling in cracked earth

370Ringed by the flat horizon only

371What is the city over the mountains

372Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air

373Falling towers

374Jerusalem

Athens

Alexandria

375Vienna

London

376Unreal

377A woman drew her long black hair out tight

45

378And fiddled whisper music on those strings

379And bats with baby faces in the violet light

380Whistled, and beat their wings

381And crawled head downward down a blackened wall

382And upside down in air were towers

383Tolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hours

384And voices singing out of empty cisterns and exhausted wells.

385In this decayed hole among the mountains

386In the faint moonlight, the grass is singing

387Over the tumbled graves, about the chapel

388There is the empty chapel, only the wind’s home.

46

389It has no windows, and the door swings,

390Dry bones can harm no one.

391Only a cock stood on the rooftree

392Co co rico co co rico

393In a flash of lightning. Then a damp gust

394Bringing rain

395Ganga was sunken, and the limp leaves

396Waited for rain, while the black clouds

397Gathered far distant, over Himavant.

398The jungle crouched, humped in silence.

399Then spoke the thunder

400DA

401Datta: what have we given?

402My friend, blood shaking my heart

403The awful daring of a moment’s surrender

47

404Which an age of prudence can never retract

405By this, and this only, we have existed

406Which is not to be found in our obituaries

407Or in memories draped by the beneficent spider

408Or under seals broken by the lean solicitor

409In our empty rooms

410DA

411Dayadhvam: I have heard the key

412Turn in the door once and turn once only

413We think of the key, each in his prison

414Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison

415Only at nightfall, aetherial rumours

48

416Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus

417DA

418Damyata: The boat responded

419Gaily, to the hand expert with sail and oar

420The sea was calm, your heart would have responded

421Gaily, when invited, beating obedient

422To controlling hands

423I sat upon the shore

424Fishing, with the arid plain behind me

425Shall I at least set my lands in order?

426London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down

49

427Poi s’ascose nel foco che gli affina

428Quando fiam ceu chelidon — O swallow swallow

429Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie

430These fragments I have shored against my ruins

431Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo’s mad againe.

432Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

433Shantih shantih shantih

This is a reference to the ancient city of Carthage, which was located in

what is now Tunisia. Carthage was a major center of trade and civilization

in the ancient Mediterranean world, but it was destroyed by the Romans in

the Punic Wars in the 2nd century BCE. The use of Carthage in the poem may

suggest themes of destruction, decay, and the decline of civilization. The

city of Carthage has been interpreted as a symbol of the failure and fall of

human civilizations, which can serve as a warning for modern society. The

image included in this annotation, via Wikimedia Commons, shows

a representation of the ancient city from the Carthage National Museum in

Tunisia.

- [ZO]

308Burning burning burning burning

309O Lord Thou pluckest me out

310O Lord Thou pluckest

311burning

39

IV. DEATH BY WATER

312PHLEBAS the Phoenician, a fortnight dead,

313Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep sea swell

314And the profit and loss.

315A current under sea

316Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell

317He passed the stages of his age and youth

318Entering the whirlpool.

319Gentile or Jew

320O you who turn the wheel and look to windward,

321Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

40

V. WHAT THE THUNDER SAID

322AFTER the torchlight red on sweaty faces

323After the frosty silence in the gardens

324After the agony in stony places

325The shouting and the crying

326Prison and palace and reverberation

327Of thunder of spring over distant mountains

328He who was living is now dead

329We who were living are now dying

330With a little patience

41

331Here is no water but only rock

332Rock and no water and the sandy road

333The road winding above among the mountains

334Which are mountains of rock without water

335If there were water we should stop and drink

336Amongst the rock one cannot stop or think

337Sweat is dry and feet are in the sand

338If there were only water amongst the rock

339Dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit

340Here one can neither stand nor lie nor sit

341There is not even silence in the mountains

42

342But dry sterile thunder without rain

343There is not even solitude in the mountains

344But red sullen faces sneer and snarl

345From doors of mudcracked houses

346If there were water

346And no rock

347If there were rock

348And also water

349And water

350A spring

351A pool among the rock

352If there were the sound of water only

353Not the cicada

354And dry grass singing

355But sound of water over a rock

43

356Where the hermit-thrush sings in the pine trees

357Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop

358But there is no water

359Who is the third who walks always beside you?

360When I count, there are only you and I together

361But when I look ahead up the white road

362There is always another one walking beside you

363Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

364 I do not know whether a man or a woman

365—But who is that on the other side of you?

44

366What is that sound high in the air

367Murmur of maternal lamentation

368Who are those hooded hordes swarming

369Over endless plains, stumbling in cracked earth

370Ringed by the flat horizon only

371What is the city over the mountains

372Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air

373Falling towers

374Jerusalem

Athens

Alexandria

375Vienna

London

376Unreal

377A woman drew her long black hair out tight

45

378And fiddled whisper music on those strings

379And bats with baby faces in the violet light

380Whistled, and beat their wings

381And crawled head downward down a blackened wall

382And upside down in air were towers

383Tolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hours

384And voices singing out of empty cisterns and exhausted wells.

385In this decayed hole among the mountains

386In the faint moonlight, the grass is singing

387Over the tumbled graves, about the chapel

388There is the empty chapel, only the wind’s home.

46

389It has no windows, and the door swings,

390Dry bones can harm no one.

391Only a cock stood on the rooftree

392Co co rico co co rico

393In a flash of lightning. Then a damp gust

394Bringing rain

395Ganga was sunken, and the limp leaves

396Waited for rain, while the black clouds

397Gathered far distant, over Himavant.

398The jungle crouched, humped in silence.

399Then spoke the thunder

400DA

401Datta: what have we given?

402My friend, blood shaking my heart

403The awful daring of a moment’s surrender

47

404Which an age of prudence can never retract

405By this, and this only, we have existed

406Which is not to be found in our obituaries

407Or in memories draped by the beneficent spider

408Or under seals broken by the lean solicitor

409In our empty rooms

410DA

411Dayadhvam: I have heard the key

412Turn in the door once and turn once only

413We think of the key, each in his prison

414Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison

415Only at nightfall, aetherial rumours

48

416Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus

417DA

418Damyata: The boat responded

419Gaily, to the hand expert with sail and oar

420The sea was calm, your heart would have responded

421Gaily, when invited, beating obedient

422To controlling hands

423I sat upon the shore

424Fishing, with the arid plain behind me

425Shall I at least set my lands in order?

426London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down

49

427Poi s’ascose nel foco che gli affina

428Quando fiam ceu chelidon — O swallow swallow

429Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie

430These fragments I have shored against my ruins

431Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo’s mad againe.

432Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

433Shantih shantih shantih

BY

T. S. ELIOT

"Nam Sibyllam quidem Cumis ego ipse oculis meis vidi in ampulla pendere, et cum illi pueri dicerent: Σίβυλλα τί θέλεις; respondebat illa: ἀποθανεῖν θέλω." epigraphepigraphThis is a quote from the first-century Roman prose work Satyricon (c.54-68) believed to be by Gaius Petronius (27-66CE). Eliot translated the epigraph as follows: "I saw with my own eyes the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in a cage, and when the boys said to her: 'Sibyl, what do you want?' she answered: 'I want to die.'" - [TH] NEW YORK

BONI AND LIVERIGHT1922 9 I. THE BURIAL OF THE DEAD 1APRIL is the cruellest monthChaucer, breeding ChaucerThe first line of The Waste Land alludes to the General Prologue of Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, which opens with a "description of Spring characteristic of dream visions of secular love" (Harvard). Chaucer's poem begins, in modern English, as follows: When April with its sweet-smelling showers THas pierced the drought of March to the root, And bathed every vein (of the plants) in such liquid By which power the flower is created; When the West Wind also with its sweet breath In every wood and field has breathed life into The tender new leaves, and the young sun Has run half its course in Aries, And small fowls make melody, Those that sleep all the night with open eyes (So Nature incites them in their hearts), Then folk long to go on pilgrimages, And professional pilgrims to seek foreign shores, To distant shrines, known in various lands.... (General Prologue, 1-14) You might consider how Eliot's version compares to this source text. - [TH] 2Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing 3Memory and desire, stirring 4Dull roots with spring rain. 5Winter kept us warm, covering 6Earth in forgetful snow, feeding 7A little life with dried tubers. 8Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee 9With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade, 10And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten, 10 11And drank coffee, and talked for an hour. 12Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch.identity identity In this passage, the female speaker's statement, "I am not Russian at all; I come from Lithuania, really German," introduces the theme of fragmentation and displacement that permeates the poem. The speaker's identity is shaped by multiple cultural influences, resulting in a fragmented sense of self. She does not fully identify as Russian, Lithuanian, or German, but as a hybrid of all three. This complex identity further highlights the themes of displacement and cultural conflict throughout the work. - [ZO] 13And when we were children, staying at the archduke’s, 14My cousin’s, he took me out on a sled, 15And I was frightened. He said, Marie, 16Marie, hold on tight. And down he went. 17In the mountains, there you feel free. 18I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter. 19What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow 20Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man, 11 21You cannot say, or guess, for you know only 22A heap of broken images, where the sun beats, 23And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, 24And the dry stone no sound of water. Only 25There is shadow under this red rock, 26(Come in under the shadow of this red rock), 27And I will show you something different from either 28Your shadow at morning striding behind you 29Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you; 12 30I will show you fear in a handful of dust. 31FrischWagner weht der Wind 32Der-Heimat zu 33Mein Irisch Kind, 34Wo weilest du? Wagner

These lines are quoted from Richard Wagner's Tristan und

Isolde (1865), a German opera based on a 12th century chivalric tragic

poem Tristan and Iseult. There are multiple different

versions of the story, but at root, it is a Celtic legend about tragic love; the

knight Tristan has been tasked with accompanying the Irish maiden Iseult to be

married to his uncle, the King of Cornwall. On the way, Tristan and Iseult fall

deeply in love, which causes many tempestuous problems. The story became very

popular in the ninteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially among the

Pre-Raphaelites, a group of artists and writers influenced by Romanticism who

sought inspiration in Italian Renaissance art and medieval courtly themes. The

image included here, by the Pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse, is Tristan and Isolde with the Potion (1916), via Wikimedia Commons. Tristan and Iseult are on the ship heading for

Cornwall and Iseult's marriage; they are drinking a love potion. The lines are

from the first act of Tristan und Isolde, and are sung by

an anonymous sailor about his lover, left behind in Ireland. Translated, the lines

read "Fresh blows the wind / homeward: / my Irish maid, / where do you linger?" A

later line (42, below) from the same opera, "Empty and desolate is the sea,"

sandwiches Eliot's description of the first meeting between the "hyacinth girl"

(36) and her lover, who remembers being struck by her and feeling "neither /

Living nor dead" (39-40). ( - [TH]

35“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

36“They called me the hyacinth girl."

37—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden,

38Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

39Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

40Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

41Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

13

42Oed’ und leer das Meer.

43Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyanteclairvoyant,

clairvoyant

This noun comes from the word "clairvoyance", which in the French means

clear-sighted. A clairvoyant is what we would now call a psychic, someone

who can see things that are not physically there. Madame Sosostris is a

fortune teller who has a reputation as "the wisest woman in Europe." The -e

is added to the word clairvoyant to make it feminine in the French (OED).

- [CP]

44Had a bad cold, nevertheless

45Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe,

46With a wicked pack of

cardscardscardsA character in Eliot's poem visits a famous fortune

teller, and the following lines describe the tarot cards she received at a

reading. According to Elizabeth DeBold of the Folger Shakespeare Library, tarot originated in 14th-century

Egypt, and traveled to Europe during the Renaissance. - [TH]. Here, said

she,

47Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

48(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

49Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

50The lady of situations.

51Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

14

52And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

53Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

54Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

55The Hanged Man. Fear death by

waterwater.

water

Water is a prevalent motif throughout The Waste

Land. Water is often associated with regeneration/rebirth, but here and

elsewhere, it is associated with death.

- [CP]

56I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring.

57Thank you. If you see dear Mrs. Equitone,

58Tell her I bring the horoscope myself:

59One must be so careful these days.

60Unreal City,

61Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

15

62A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

63I had not thought death had undone so many.

64Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

65And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

66Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

67To where Saint Mary

Woolnothwoolnothwoolnoth

These lines are quoted from Richard Wagner's Tristan und

Isolde (1865), a German opera based on a 12th century chivalric tragic

poem Tristan and Iseult. There are multiple different

versions of the story, but at root, it is a Celtic legend about tragic love; the

knight Tristan has been tasked with accompanying the Irish maiden Iseult to be

married to his uncle, the King of Cornwall. On the way, Tristan and Iseult fall

deeply in love, which causes many tempestuous problems. The story became very

popular in the ninteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially among the

Pre-Raphaelites, a group of artists and writers influenced by Romanticism who

sought inspiration in Italian Renaissance art and medieval courtly themes. The

image included here, by the Pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse, is Tristan and Isolde with the Potion (1916), via Wikimedia Commons. Tristan and Iseult are on the ship heading for

Cornwall and Iseult's marriage; they are drinking a love potion. The lines are

from the first act of Tristan und Isolde, and are sung by

an anonymous sailor about his lover, left behind in Ireland. Translated, the lines

read "Fresh blows the wind / homeward: / my Irish maid, / where do you linger?" A

later line (42, below) from the same opera, "Empty and desolate is the sea,"

sandwiches Eliot's description of the first meeting between the "hyacinth girl"

(36) and her lover, who remembers being struck by her and feeling "neither /

Living nor dead" (39-40). ( - [TH]

35“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

36“They called me the hyacinth girl."

37—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden,

38Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

39Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

40Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

41Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

13

42Oed’ und leer das Meer.

43Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyanteclairvoyant,

clairvoyant

This noun comes from the word "clairvoyance", which in the French means

clear-sighted. A clairvoyant is what we would now call a psychic, someone

who can see things that are not physically there. Madame Sosostris is a

fortune teller who has a reputation as "the wisest woman in Europe." The -e

is added to the word clairvoyant to make it feminine in the French (OED).

- [CP]

44Had a bad cold, nevertheless

45Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe,

46With a wicked pack of

cardscardscardsA character in Eliot's poem visits a famous fortune

teller, and the following lines describe the tarot cards she received at a

reading. According to Elizabeth DeBold of the Folger Shakespeare Library, tarot originated in 14th-century

Egypt, and traveled to Europe during the Renaissance. - [TH]. Here, said

she,

47Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

48(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

49Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

50The lady of situations.

51Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

14

52And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

53Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

54Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

55The Hanged Man. Fear death by

waterwater.

water

Water is a prevalent motif throughout The Waste

Land. Water is often associated with regeneration/rebirth, but here and

elsewhere, it is associated with death.

- [CP]

56I see crowds of people, walking round in a ring.

57Thank you. If you see dear Mrs. Equitone,

58Tell her I bring the horoscope myself:

59One must be so careful these days.

60Unreal City,

61Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

15

62A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

63I had not thought death had undone so many.

64Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

65And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

66Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

67To where Saint Mary

Woolnothwoolnothwoolnoth Saint Mary

Woolnoth is an Anglican church in London, first built in the 12th century,

then rebuilt on several occasions. The photograph included here, from about

1900, originally from the Library of Congress, shows the church in its

modern form, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoore and opened in 1727. This is

likely very close to what Eliot would have seen. It is possible that the

site had been a place of worship for 2000 years (Wikipedia).

- [TH] kept the hours

68With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

69There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: “Stetson!

70“You who were with me in the ships at MylaemylaemylaeThe Battle of

Mylae, a naval battle won in 260BCE by Roman naval

forces. - [TH]!

17

71“That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

72“Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

73“Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

74“O keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

75“Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!

76“You!

hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!baudelairebaudelaireThis is an allusion to the last line of Charles

Baudelaire's introductory poem "Au Lecteur [To the Reader]" from his

collection Fleurs du mal [Flowers of Evil

(1857-1868). The line reads, "Hypocritical reader, --my twin, --my

brother!" You can read Baudelaire's poems online. - [TH]"

16

II. A GAME OF CHESS

77The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,

78Glowed on the marble, where the glass

79Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines

80From which a golden Cupidoncupidon peeped out

cupidon

Saint Mary

Woolnoth is an Anglican church in London, first built in the 12th century,

then rebuilt on several occasions. The photograph included here, from about

1900, originally from the Library of Congress, shows the church in its

modern form, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoore and opened in 1727. This is

likely very close to what Eliot would have seen. It is possible that the

site had been a place of worship for 2000 years (Wikipedia).

- [TH] kept the hours

68With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

69There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: “Stetson!

70“You who were with me in the ships at MylaemylaemylaeThe Battle of

Mylae, a naval battle won in 260BCE by Roman naval

forces. - [TH]!

17

71“That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

72“Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

73“Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

74“O keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

75“Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!

76“You!

hypocrite lecteur!—mon semblable,—mon frère!baudelairebaudelaireThis is an allusion to the last line of Charles

Baudelaire's introductory poem "Au Lecteur [To the Reader]" from his

collection Fleurs du mal [Flowers of Evil

(1857-1868). The line reads, "Hypocritical reader, --my twin, --my

brother!" You can read Baudelaire's poems online. - [TH]"

16

II. A GAME OF CHESS

77The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,

78Glowed on the marble, where the glass

79Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines

80From which a golden Cupidoncupidon peeped out

cupidon

The scene

described by the speaker features banners adorned with fruit-bearing vines

and a standard depicting a golden "Cupidon," an alternate name for the Roman

god of love, Cupid. The use of Cupidon in this context evokes themes of

desire, fertility, and the pursuit of romantic love. The image of Cupidon

peeking out from behind the banner may also imply a sense of voyeurism or

hidden desire, contributing to an undercurrent of sexual tension in the

scene. This lush, sensual imagery is suggestive of the speaker's heightened

sensibility, and highlights the poem's themes of passion and desire. The

image included here, via Wikipedia, shows a Roman copy of an original Greek sculpture of

Eros Stringing His Bow.

- [ZO]

81(Another hid his eyes behind his wing)

82Doubled the flames of sevenbranched candelabra

83Reflecting light upon the table as

84The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it,

85From satin cases poured in rich profusion.

18

86In vials of ivory and coloured glass

87Unstoppered, lurked her strange synthetic perfumes,

88Unguent, powdered, or liquid—troubled, confused

89And drowned the sense in odours; stirred by the air

90That freshened from the window, these ascended

91In fattening the prolonged candle-flames,

92Flung their smoke into the laquearia,

93Stirring the pattern on the coffered ceiling.

94Huge sea-wood fed with copper

95Burned green and orange, framed by the coloured stone,

96In which sad light a carvèd dolphin swam.

19

97Above the antique mantel was displayed

98As though a window gave upon the sylvan scene

99The change of PhilomelphilomelphilomelAn allusion to the ancient Greek story of Philomela,

which was recounted in Ovid's Metamorphoses 6.412-674. In the story, Tereus, King of

Thrace, marries the Athenian Procne. Procne asks her husband to bring her

sister, Philomela, to visit her in Thrace. Tereus rapes Philomela, and to

keep her from telling her sister of the assault, he cuts out her tongue.

Philomela communicates her story to Procne by weaving a tapestry showing the

events. The two sisters avenge the abuse by killing Itys, Procne and Tereus'

son, and baking him into a pie which Tereus eats. The women flee, pursued by

Tereus; the gods transform the three into birds--Philomela becomes the

sweet-singing nightingale. - [TH], by the barbarous king

100So rudely forced; yet there the nightingale

101Filled all the desert with inviolable voice

102And still she cried, and still the world pursues,

103“Jug Jug" to dirty ears.

104And other withered stumps of time

105Were told upon the walls; staring forms

106Leaned out, leaning, hushing the room enclosed.

107Footsteps shuffled on the stair.

20

108Under the firelight, under the brush, her hair

109Spread out in fiery points

110Glowed into words, then would be savagely still.

111“My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

112“Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

113“What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

114“I never know what you are thinking. Think."

115I think we are in rats’ alley

116Where the dead men lost their bones.

21

117“What is that noise?"

118The wind under the door.

119“What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?"

120Nothing again nothing.

121 “Do